In 2006, when I was 14 and all tangled red hair and too much eyeliner and rampant insecurities, my ninth-grade health teacher, a sarcastic guy in his 40s, opened class one day with a single statement: “Ladies, everything can be avoided if you’ll just keep your legs closed.” Then he turned the class over to two strangers for the rest of the week, a man and a woman from a sex education organization now called Life Choices.

As teenage girls living in Crockett County, Tennessee—a cluster of five tiny towns strung together by a quiet highway, where the culture revolves around the harvesting of cotton, Friday night lights, and Sunday sermons—my friends and I knew the consequences of sex: ruined reputations, questioned faith, and the most unthinkable of all, pregnancy. We had heard the whispering in the hallways; we had read the accusations scribbled on the bathroom stalls.

One day during the weeklong sex ed class, the female instructor made a show of tearing a long piece of tape from a dispenser. She held it for us to see, taut between her fingers, and pointed out how transparent and clean and sticky it was. Then she handed it to the girl in the first row and told her to attach it to her skin and pull it off. “It won’t hurt,” she promised. The girl did as she was told, and then the piece of tape was passed around for each of us to follow suit. When it got to me, I gingerly stuck it on my left forearm, smoothing it out on my skin. After I peeled it off, I looked at the particles of dirt and dead cells and hair that now clung to the tape. I wrinkled my nose and passed it along.

Once the tape had collected bits of each of us, the instructor took it back and pinched it between her thumb and index finger. “See how dirty this piece of tape is?” she said. “It’s basically trash.” This tape, she said, could never bond well enough to stick to anything, especially not another dirty piece of tape. She pressed two fresh pieces together and made a show of her inability to separate them.

The law in Tennessee governing sex ed at the time said coursework must “include presentations encouraging abstinence from sexual intercourse during the teen and pre-teen years.” When we learned about condoms, we were told they could have microscopic holes in them that made it possible for sperm to pass through, impregnating our now-used bodies.

Then, in 2012, Tennessee legislators passed a law that marked a new extreme, requiring anyone teaching sex ed to teach abstinence as the only legitimate option, and banning any discussion that could be perceived as encouragement of “gateway sexual activity.” Educators who crossed this murky line could face legal action. (In reaction, Stephen Colbert deadpanned that “kissing and hugging are the last stop before reaching Groin Central Station,” so it’s important to ban “all the things that lead to the things that lead to sex.”) To define the key words, “sexual activity”—touching someone’s “primary genital area, groin, inner thigh, buttock or breast”—the legislators cribbed from Tennessee’s criminal code.

The federal government has been funding abstinence education for the past 35 years, even though it has never been shown to substantially lower teen pregnancy rates or prevent the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. In the final budget of his administration, President Barack Obama proposed eliminating federal funding for abstinence education. (He suggested similar cuts in his first presidential budget but was unable to get them past Congress.) A study in 2011 by researchers at the University of Georgia found that states that stressed abstinence had a roughly 25 percent higher rate of teen pregnancy than states that didn’t mention abstinence in their policies; a University of Washington study found that teens who went through comprehensive sex ed were 50 percent less likely to get pregnant than kids who had abstinence-only education. The one positive outcome of abstinence education: A 2010 study based out of the University of Pennsylvania found that middle schoolers who had been in an abstinence program were more likely to delay their first sexual experiences. But another study, published in the journal Pediatrics in 2009, showed that young people who took virginity pledges—a common practice in abstinence-only programs—were less likely to use protection when the time came.

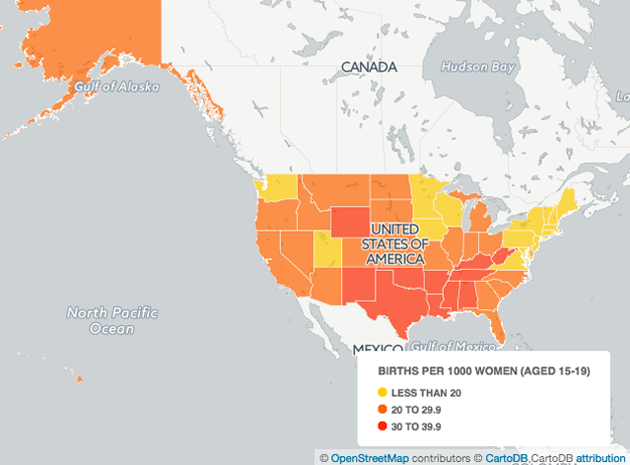

Despite the apparent failures of the abstinence approach to sex ed, half of all states now embrace it, and the trend shows no sign of abating. In 2012, Mississippi implemented a law that mandates either abstinence-only curricula or abstinence-plus curricula (which stresses abstinence but also teaches kids about contraception). In 2013, legislators in Ohio tried to pass a measure that looked a whole lot like Tennessee’s law. (In the end, it didn’t get enough support.) And last year, Texas—which is one of the most ardent abstinence states and has one of the nation’s highest teen pregnancy rates—took $3 million from the budget for HIV and STD prevention and reallocated it to abstinence ed.

Tennessee, however, is one of only two states that can fine the groups that teach sex ed for not complying with the law. Last year, Tennessee also passed a bill that requires sex ed teachers to “inform students…concerning the process of adoption and its benefits.”

As I watched my home state make headlines, I thought about my sex ed course. Nearly a decade had passed since I tore that piece of dirty tape off my arm, but for better or worse, the message stuck with me. I wondered what the teenagers growing up today among West Tennessee’s churches and farms were hearing. So I went back home.

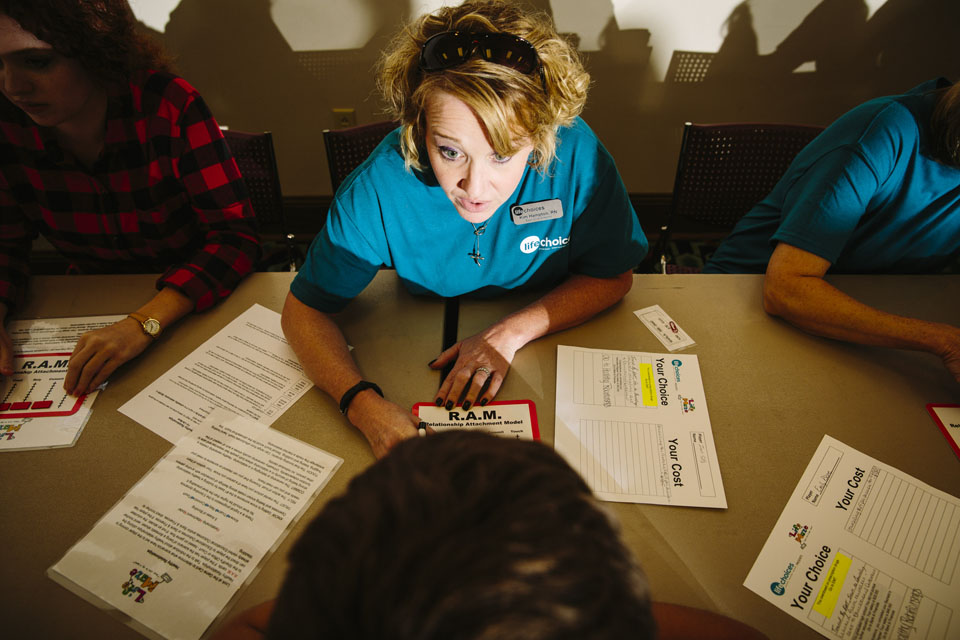

In late September of 2014, on an unseasonably cool Monday morning, I climbed into Donna Whittle’s immaculate car outside the offices of Life Choices, in the regional hub of Dyersburg. (In my day, the organization had been called Right Choices; the name was changed to make it more appealing to teens.) State law dictates that in counties where 20 or more young girls out of every 1,000 get pregnant, schools have to teach sex ed. Some of these schools contract out to groups like Life Choices, which also serves as a crisis pregnancy center.

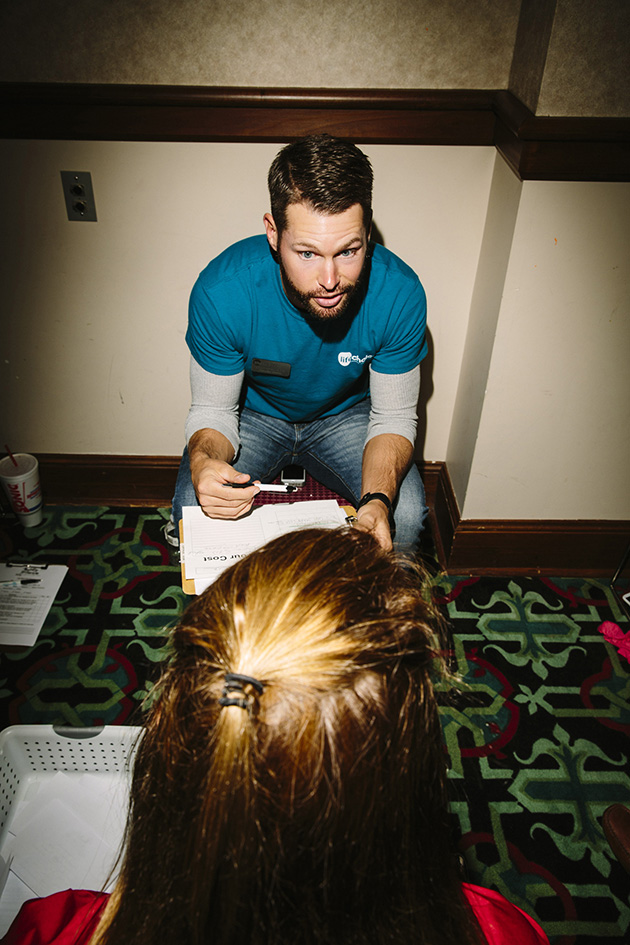

I would be spending the next four days with Whittle and her counterpart, Matt Boals, as they launched into a teaching tour that would have them speaking to about 3,000 students by the end of the school year.

That week, the pair were working at a middle school in a town where the main street was lined with fast-food restaurants and houses with peeling paint. A few historic homes with well-kept lawns formed a ring around the center of town. Twenty-one percent of the population in the county lived below the federal poverty line; the previous year, 42 of every 1,000 girls aged 15 to 17 had become pregnant—more than twice the state’s average rate. As we got closer to the school, Whittle frowned. “This is a predominantly black school, isn’t it?” she said. “I just really don’t know what to expect.”

Sex ed was held in the school’s gym, where rickety wooden bleachers stretched across a scarred hardwood basketball court. A wad of paper lay on the floor; students kicked it as they stampeded into the room. The gym teacher separated the girls and boys. That first day, those without consent forms—about half of them, either denied permission by their parents and guardians or unwilling to produce the signed slips I suspected were crumpled in their backpacks—disappeared into an adjacent room.

The boys huddled in the back rows, shoulders slumped against the benches behind them. One girl smacked her gum, dug through her bright blue purse, and glanced up disinterestedly as Boals and Whittle made their way in front of the kids. The gym teacher had the girl spit out her gum, and class began.

“Hey, y’all,” said Boals, a tall 32-year-old with blue eyes and an all-American face. Boals had taught sex ed for Life Choices a number of years earlier, but he’d left to become a firefighter. Now his wife was pregnant with their second child, so he’d come back to teaching and its more predictable schedule.

Boals and Whittle began class by chatting with the kids and showing them family photographs. Boals talked about adventures as a firefighter and his love of playing guitar; Whittle told the students that she used to work at the local newspaper. The two then turned to their presentation, and a slide titled, “To date or not to date.” On the screen was a photograph of two teenagers—a white boy and a white girl—holding hands.

Whittle asked the group, “So are y’all dating now?” The kids began debating the difference between “date” and “talk.” Boals and Whittle awkwardly tried to parse the meaning of both words. Most of the students said they just “talk”—on the phone, between classes, via text. But some insisted they date. “Well, where do y’all go on dates?” Whittle asked.

“The Burger King!” sang out a girl from the front row. “My mama pays.”

The chatter continued for a while; then Whittle flipped to another photo of two smiling white teenagers. Next to the picture was the phrase “sexual abstinence” and its definition: “saving sexual activity for a committed marriage relationship.” Boals told the kids, “We define ‘sexual activity’ as when the underwear zone of another person comes into contact with any part of your body.” The students would often be asked to recite this definition at the beginning and end of each class.

When Boals finished, a hand in the front row shot up into the air—a young girl with a thick twist of microbraids: “How old were y’all the first time you had sex?” she asked. Boals shifted his weight from one foot to another. To his credit, he didn’t pause for long. “I was in a relationship in high school for two years, and we had sex,” he said. “I was scared to death I had gotten my girlfriend pregnant…I didn’t understand how often girls got pregnant.” The girl nodded.

“We’re not here to judge you if you’ve already had sex,” Boals said gently. “When you get married, you can have all the sex you want without worrying about it.”

Later, Boals told me that he doesn’t do this work under any illusions—he knows the odds are that his students won’t wait for marriage to have sex. “But if somebody waits until they’re out of high school, they may wait until they’re a more responsible adult in college or in their later 20s.” He says his drive to work is “my time to talk to God, and I always say, ‘I don’t know what I’m going to say today, but I hope one kid—that’s all I’m asking for—hears it, and it helps him.'”

The origins of Tennessee’s current sex ed law can be traced to early 2010, when a woman who was teaching AIDS prevention to high schoolers in Nashville demonstrated how to apply a condom—by rolling it onto a dildo using her mouth.

The dubious demonstration enraged Rodrick Glover, the parent of a 17-year-old girl in the class. Glover felt that his daughter “had been violated,” so he reached out to local newspapers and got in touch with the Family Action Council of Tennessee (FACT), a Christian nonprofit that was created in 2006. FACT’s lobbying arm is a driving force behind a lot of Tennessee’s headline-making legislation around sex, including the infamous Amendment One, which recently revised the state’s constitution to say that nothing in it protects a woman’s right to an abortion.

The group’s top lobbyist, former state Sen. David Fowler, is not shy when it comes to expressing his view that same-sex marriage is a danger to Tennessee or, for that matter, his fears of a growing Islamic voting bloc. When Fowler got the call from Glover, his team went to work crafting the bill banning teachers from discussing any behavior that could lead to sex before marriage.

When the abstinence bill came up for debate in April 2012, state legislators talked about it with great visible discomfort. Mike Turner, a Democrat from Nashville, stiffly joked, “Well, the bill itself gets pretty explicit. Matter of fact, when I read it the first time, I had to ask Representative Sargent for a cigarette before I got done reading it.” Turner’s colleagues giggled nervously before he was scolded by Republican Jim Gotto, one of the bill’s sponsors. (Female representatives, who made up only 17 percent of the state House, remained silent.) John DeBerry Jr. waved his spectacles about as he voiced his approval of the bill and added, “Everybody in this room knows what gateway sexual activity is. Everybody knows that there’s certain buttons, when you push ’em—certain switches, when you turn ’em on—there’s no stopping, especially for undisciplined, untrained, untaught, and unraised children who just want affection from somebody or anybody.” The bill passed with overwhelming support.

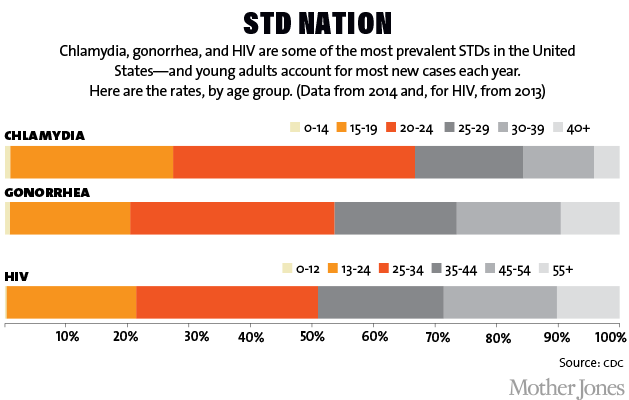

There are plenty of reasons to talk to teens about sex—especially in West Tennessee. Sexually transmitted diseases, particularly gonorrhea and chlamydia, are rampant in 15- to 24-year-olds in this part of the state. In the middle of the week, Kim Hampton, the executive director of Life Choices who is also a nurse, joined Boals and Whittle to usher the kids through something I remember all too well from my days as a student in sex ed class: Picture Day.

Hampton, a petite blonde with curly hair and bright green eyes, began to click through gruesome images: mouths and eyes infected with the scars, rashes, and painful-looking blisters of syphilis and other STDs. With each slide, she told the students how the disease could be contracted (contact with the “underwear zone”), what its symptoms were (“painful, lifelong, recurring sores on the genitals and the mouth”), and how it could be treated (actually, it “may not be curable”).

“What’s the only for-sure way to not get any of these diseases or get pregnant?” Hampton asked. She waited patiently to hear the word “abstinence.” Then she asked, “And what is sex for?” She paused, and when the students looked around uncertainly, she answered, “For making babies, for having a kid.”

Hampton paused on a photograph of sores caused by syphilis. “If you kiss this person, what’s going to happen?” she asked the class.

“You gonna be dead,” a boy in the back muttered.

Hampton told the class that even though the media tells us that condoms can protect us from STDs, it isn’t completely true. She clicked to a slide that read, “Condoms fail 1 out of 3 times for HIV; fail 1 out of 4 times for pregnancy; do not protect against HPV/Herpes.” As each new slide went by, the kids’ expressions flashed between horror and fascination. One boy was so overwhelmed that he fainted.

Before she sent her students off to lunch, Hampton came back to the issue of birth control. “About the Pill,” she said, peering at the students. “Let’s think about it like this: If I want to go up on a roof, and I have always wanted to jump off a big building, is that safe?”

“Noooooo,” the students chorused.

“Well.” She walked over to the bleachers, picked up a comically large camouflage umbrella, and opened it. “What if I use this Ducks Unlimited umbrella for some resistance? Is it safe then?”

“Noooooo.”

“But it’s saf-er, right? I might just break a couple bones? That’s what birth control is. It’s saf-er, but not safe.” This added to something Whittle had told the group earlier: “There will never be any kind of birth control that teaches faithfulness, trustworthiness, responsibility, and commitment.”

Boals, Whittle, and Hampton are all practicing Christians. They are careful in the classroom to avoid any direct discussion about their religion. Away from school, they talk about their faith frequently because it is a strong, positive force in their lives.

Many of their messages—don’t get pregnant in high school, know how to avoid STDs—are important for teens to hear. So are the messages in the coursework about the negative effects that young women can face (eating disorders, anxiety) because of insecurities around body image and pressure to fit an ideal that men find pleasing. There are also positive messages for boys, assuring them that what they are feeling about sex and attraction is normal.

But back in July, I sat in on a teacher-training session with Boals, Whittle, and Hampton. In a dark, excessively air-conditioned room in the Life Choices headquarters, we watched a series of training videos about traditional views on marriage and family. The videos came from a Chattanooga-based company called On Point, founded in the early ’90s to produce abstinence curricula that have been used in 40 US states and 13 countries, according to the company’s website. In the first video, a man lectured to an audience of teachers and children at a middle school. As he paced back and forth across the stage, he threw questions to his listeners: What is the mother’s role in the family? What are her responsibilities?

Audience members shouted back: “Cooks!” “Laundry!” “Cleans!” “Takes care of the kids!”

He wrote the answers down in a column labeled “Mother.” Then he asked for the father’s role.

“Goes to work!” “Pays bills!” “Disciplines!”

After recording the responses, he paused to tell the audience that sometimes single mothers have to take on a father’s jobs too, if their families are left fatherless from war. War, it seemed, was the only good excuse for single motherhood. “This,” he said, gesturing to the previous answers, “is what the family is supposed to look like.”

In another video, a male instructor referred to breasts as “boobies” and said guys are stimulated by sight, so if a woman isn’t properly covered “she’s easy.” Then he added, “That’s what she’s advertising.”

One day in class, Whittle picked four boys and one energetic girl to act in an On Point version of The Bachelorette. The girl was supposed to choose the boy who would make the best husband. Each of the boys was given a backstory: One had gotten a girl pregnant; another was a ladies’ man who had slept around. A third was a quarterback who worked for Habitat for Humanity on the weekends and had chosen abstinence—but had fallen prey to “Catwoman,” as the curriculum called her, and she had convinced him to have sex. Then Catwoman moved on, and the quarterback was left to wonder if he could ever love a woman again. The last of the bachelors was Clark Kent, a great guy who had decided on abstinence early on. “He protected his heart and stuck with it. He waited for her,” Boals said. The boy playing Clark Kent dramatically dropped to one knee, and the willowy preteen girl burst into giggles and accepted his proposal with a flourish. “I say, for a girl or woman, be picky,” Boals declared.

In its coursework, Life Choices uses the words “emotional,” “mental,” and “spiritual” to try to get kids to think about the consequences of sex beyond physical outcomes. The phrase “protected his heart,” though, caught my attention. It echoed the sermons and Christian youth gatherings that taught me to “guard my heart” against men who would distract me from God.

Church leaders and Life Choices instructors both stress that promiscuity or premarital sex will lead to a guilt that will weigh heavily on someone for a long time. When I think about that guilt, I think about Picture Day all those years ago. That was the day many of us saw the genitals of the opposite sex for the first time—which meant the first penis I ever saw was covered in sores. “I had never seen healthy male genitals before, much less ones that looked infected,” a high school friend of mine recalls. We were horrified. It is undoubtedly important to convey the dangers of STDs to kids, but when I saw sores and lesions on a person’s privates, I also saw shame. Those blemishes were like a scarlet letter worn below the belt.

Every fall around Halloween, the Life Choices instructors take a break from the classroom to put on a community outreach event in Dyersburg called the Life Maze. A big draw for schools and church groups, the maze is modeled after the board game Life and aims to show teens the possible consequences of the choices they make. Lots of local businesses and organizations pitch in—the funeral home lends the event a casket, which is outfitted with a mirror so you can see yourself if you peer in. A judge presides over the fate of a faux drunk driver. The sheriff’s office brings a lot of PVC pipe and fashions it into a jail—to demonstrate what happens if a kid is convicted of drunk driving or, say, caught with drugs. There are mannequins dressed in wedding attire; recruiters from the National Guard coach the kids in pushups.

Hampton told me that in 2014, one of the middle schools where she teaches hadn’t had a single pregnancy all year—a first. A health coordinator for another school system where Life Choices teaches stated on the group’s website that over the course of two decades, her county had seen a drop from about 50 pregnancies a year to 30 or 35.

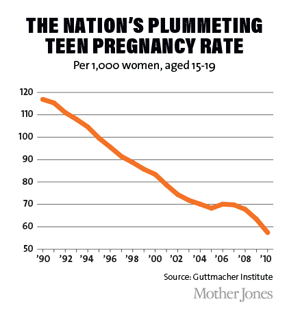

This seems like a victory for the organization—certainly its curriculum played a large role in my decision to not have sex in high school. But teen pregnancy rates have plummeted across the country—down 51 percent between 1990 and 2010. There is no clear evidence about the reasons, says Heather Boonstra, the director of public policy at the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive health and sexuality think tank, but she says the data points to better contraceptives and better use of them.

She mentions, though, the 2009 data showing that teens who signed virginity pledges were less likely to use protection when they did have sex. “Teens are possibly putting themselves at greater risk because they’re not prepared,” she adds. According to a report by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, 41 percent of 18- and 19-year-olds say they know little or nothing about condoms, and 75 percent say they know little or nothing about the Pill.

What’s more, STD rates are highest among teens and young adults. In November, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that people between the ages of 15 and 24 make up a quarter of the sexually active population, yet they accounted for about half of all reported cases of gonorrhea and almost two-thirds of reported cases of chlamydia in 2014.

One evening after class with Boals and Whittle, I met up with a former high school classmate. She is a lesbian, and I asked her what she remembered about our time in sex ed class. She was quiet for a minute before telling me that on the final day of our class she had approached the woman who was teaching and asked, “Well, what if you’re gay? Can you still get sick? You can’t get pregnant.” The instructor asked, “Are you?” My classmate walked away, terrified that this woman she barely knew would out her to our small community that was largely intolerant of gays and lesbians. Later, I sat down with Boals and Whittle at a beat-up table in the corner of the gym and recounted my friend’s story.

Shaking his head, Boals said, “That’s why you have to be so careful about what you say and how you handle questions like that. Personally, I have certain beliefs, and my beliefs to the very core, at the end of the day, ask me to love people.” He added, “If I say something that they’re going to remember for the rest of their life, I haven’t done what I’m asked to do.” He looked down at his hands.

Hampton has three teenagers, and she sets aside plenty of time with them—for yoga and shopping with her daughters, movies with her son. “I’m the chaperone queen,” she told me one day. I could see why her home would be a popular spot—she’s vivacious, charming, and a straight shooter. “I did not come from a real healthy family life,” she explained. “I wasn’t taught a lot of the things that I think kids need to be told.” She wants more for her kids. “I want my son to feel like he has the freedom to go and say, ‘I woke up with an erection, what is this?'” She paused. “Open communication, we want them to have that.”

Yet looking around the gym during the Life Choices course, I saw girls every bit as curious and hopeful as I had been at their age. Their community had a different racial makeup than mine did, but they were likely living with some of the same expectations and hearing some of the same sermons—ones that come with being born Southern and female. It seemed misguided to tell girls raised in a place that suffers from historically high teen pregnancy rates that contraception is ineffective.

I wanted to tell those girls that there is never a day I regret leaving behind my high school boyfriend and moving away. Most of my former classmates are still in my hometown—their children now sit in the same classrooms we once sat in—but I’m not sure all those who stayed felt they had a choice.

Heading to my parents’ house from the training one evening on the winding back roads where I learned to drive, I remembered the first time I’d experienced sexual desire, and I wished someone had been there to explain that I didn’t have to feel sinful for simply going through puberty. Instead, when I’d had a surge of feelings about a boy, I heard the phrase, “Keep your legs closed.” And I thought of dirty Scotch tape.

I don’t regret abstaining in high school, but the fear I picked up along the way hasn’t been easy to shake. I’d believed that sperm could swim through the holes in condoms and impregnate anyone stupid enough to rely on them. It appeared to me that there was no good way to have sex until you wanted a baby, and I didn’t understand what changed once you were married, if birth control wasn’t protection enough. Surely the Pill can’t tell if you wear a wedding band.

When I did start having sex in my early 20s, even though I loved the man I was with, part of me felt disgusted with my body and overwhelmed by the experience. I couldn’t figure out what I liked because I grew up hearing that I wasn’t supposed to like any of it. I felt paralyzing shame at a basic expression of love.

On our final afternoon together, Whittle told me that she didn’t see a better way to teach sex education than through abstinence. “For people who are concerned that abstinence-based education isn’t really effective, I just want to know—do they really think 12-, 13-, and 14-year-olds need to be having sex?” she asked, her voice rising. “Because everything that we see tells us that no, they should not be. At least for this age group, I think we’re teaching exactly what we need to hear.”

While the laws in Tennessee have become more restrictive, not much has changed for Life Choices. At the end of the week Boals told me it was nice to meet someone who remembered the class from years ago. I hesitated and then—feeling more like the teenager I once was than a reporter—awkwardly mentioned the tape exercise. Boals nodded. He recalled the tactic. As we walked out of the school, Whittle turned to him and said, “We should start doing that again.”