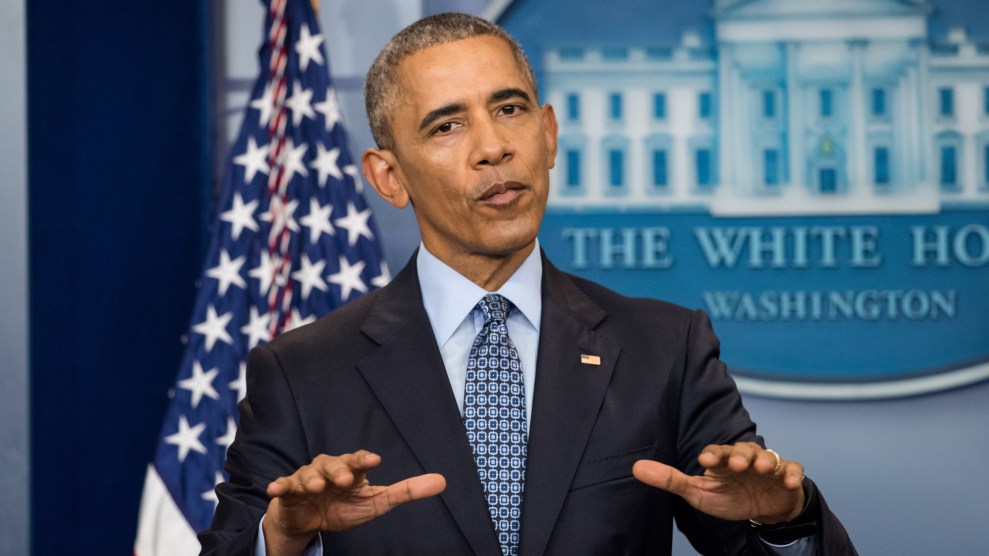

Ken Cedeno/ZUMA

After Republicans abandoned their bill to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act on Friday, party leaders all but conceded that Obamacare is here to stay—at least for a while. “We’re going to be living with Obamacare for the foreseeable future,” House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) said at a hastily arranged press conference half an hour after he yanked the bill. President Donald Trump sounded a similar note, saying that it’s time for Congress to move on to tax reform.

Both Ryan and Trump warned that the failure of their bill was devastating news for the US health care system—though not necessarily bad news for the GOP. Obamacare, they argued, would inevitably fall apart, and Democrats would be blamed for its downfall. “I’ve been saying for the last year and a half that the best thing we can do politically speaking is let Obamacare explode,” Trump said from the Oval Office Friday. “It is exploding right now.”

“It will be dead soon,” White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer said Monday afternoon.

The idea that Obamacare is in a death spiral was central to Republican efforts to destroy the law. They point to rising premiums for individuals on Healthcare.gov and insurers fleeing some markets. Thirty-two percent of counties now have only one insurance provider, up from 7 percent of counties in 2016.

But the truth is more complicated than the GOP wants you to believe. Yes, in some states there are problems with the individual insurance marketplaces created by the law. But those problems don’t exist everywhere in the country, and experts expect even the problematic markets to stabilize. That isn’t to say Obamacare is completely out of the woods, and perhaps the biggest danger facing the law comes from Trump himself. There are plenty of ways the administration could use its regulatory power to blow up the program—more on that below.

To understand the problems facing Obamacare’s marketplaces, you first need to understand what the law actually does. Before the ACA, there was a mishmash of incomprehensible plans in the individual market. For consumers, it was often extremely difficult to figure out what the plans would actually cover, and insurers were free to reject applicants or jack up prices to astronomical rates for people with preexisting conditions.

Obamacare simplified all that. Insurers would no longer be allowed to reject people because of preexisting medical conditions. In order to make that financially feasible for insurance companies, the law included an individual mandate requiring people—including young, healthy people with few medical expenses—to sign up for insurance or pay a penalty. Insurance plans would now have to meet a set of standards, and there’d be tiers of plans—Bronze, Silver, Gold, and Platinum—which offered predictable benefits. And the government would offer subsidies to help lower-income families afford coverage.

The vast majority of the law’s provisions—ending lifetime limits for coverage, allowing children to stay on their parents insurance until they’re 26, capping patients’ out-of-pocket expenses, blocking insurance companies from screening out preexisting conditions—have quietly become popular. But the high-visibility individual insurance market, on which 7 percent of the country now gets health insurance, has run into trouble. More sick people have bought insurance than expected, and costs have risen as fewer young people than predicted have signed up. Insurance is basically just cost-sharing between large groups of people, so having a pool of sicker, more expensive people creates a vicious cycle that causes the cost of premiums to increase, which further discourages healthy people from participating.

Over the past year, the costs of premiums spiked and insurers left the market. That’s left people afraid that massive rate jumps are the new norm, and that skyrocketing premium costs will cause consumers to flee. But that isn’t as large of a problem as politicians and some in the media have suggested. When the markets first opened in 2013, insurance companies initially priced their plans far below expected, so the sudden increase is actually bringing costs closer to what the architects of Obamacare expected back when they were crafting the bill. And the vast majority of people buying insurance on those markets have been insulated from those premium increases. Of the 12.2 million who bought into the 2017 open enrollment, 10.1 million received some assistance from the government to offset those costs. The government caps how much these people have to pay, as a percentage of their income.

While premiums for 2017 were projected by the government to jump 22 percent, most people won’t see that increase themselves. As Kaiser Family Foundation pointed out, for a 40-year-old making $40,000 in Birmingham, Ala., the cost of premiums for a Silver plan without subsidies jumped from $288 per month in 2016 to $492 in 2017. But that 40-year-old’s personal responsibility after the subsidies kick in stayed essentially the same: $208 per month in 2016, $207 in 2017.

Jon Gabel and Heidi Whitmore, a pair of researchers writing at Health Affairs last month, dug into the stats on these rising premiums and speculated that the rate increases could be a natural part of the “underwriting cycle,” with insurers struggling to properly estimate their costs and then overcorrecting. Gabel and Whitmore argued that a full death spiral is unlikely since most people buying insurance on the marketplace receive subsidies to offset premium spikes. “Premium growth for 2018 might be modest,” they write. “Many insurers would be expected to re-enter the marketplaces once premiums are set at a level that permits modest profits.”

According to the Congressional Budget Office, when it scored the GOP’s repeal plan, Obamacare’s individual markets should remain stable going forward: “The subsidies to purchase coverage combined with the penalties paid by uninsured people stemming from the individual mandate are anticipated to cause sufficient demand for insurance by people with low health care expenditures for the market to be stable.”

Moreover, the problems are not equally distributed across the country. One major reason appears to relate to Obamacare’s expansion of Medicaid. The ACA pushed states to enroll everyone below 138 percent of the federal poverty line into Medicaid, which is separate from the individual insurance marketplaces. The federal government pays for the vast majority of Medicaid expansion costs. But after the Supreme Court said states didn’t have to adopt the expansion, a number of Republican-controlled states rejected the program. So far, only 31 states and the District of Columbia have expanded Medicaid through Obamacare.

There’s a direct correlation between the cost of insurance premiums and whether or not a state has adopted Medicaid expansion. A 2016 study found that premiums were 7 percent higher in non-expansion states after controlling for other factors. In the non-expansion states, people who would otherwise end up on Medicaid buy insurance on the individual market—they’re about 40 percent of the marketplaces in these states. And since poor health has been tied to lower incomes, this group ends up driving up the cost of individual insurance for everyone else. Now that Obamacare is more settled as the law of the land, it wouldn’t be surprising to see a few more Republican states adopt the federal funding for expansion to shore up their marketplaces. (Republicans lawmakers in Kansas are currently pushing a bill to do just that, despite a veto threat from the state’s GOP governor.)

So Obamacare probably isn’t destined to explode, but that doesn’t mean Trump’s prediction won’t come true. It’ll just be his fault if that happens, not Barack Obama’s or Nancy Pelosi’s. Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price has wide discretion over a number of ACA provisions that that could allow him to sabotage the law. At Politico last week, Dan Diamond wondered, “Is Trumpcare already here?” He pointed out that the Trump administration has already begun to implement its agenda through executive action.

The president’s team started early in its Obamacare assault, canceling ads in late January encouraging people to sign up for insurance on the marketplaces during open enrollment, despite the fact that the ads had already been purchased. It was a clear attempt to decrease participation in the program. The people most likely to sign up without inducement are people in worse health who need insurance to pay for their care, so these sort of ads boosting enrollment are essential for attracting the younger, healthier groups necessary to spread out the cost and keep premiums low.

But if the Trump administration continues to attempt to undermine the law, it likely won’t go unnoticed. Last week, Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Patty Murray (D-Wash.) announced that at their request, the inspector general at HHS is reviewing the decision to cancel the paid ads at the last minute.

“I’m glad that there will be an independent review of the Trump Administration’s decision to cut off efforts to enroll people in the ACA,” Warren said in a statement. “President Trump and congressional Republicans have made clear that their priorities include destroying the protection that ACA gives millions of families. HHS’s move to halt outreach for ACA enrollment could contribute to weakening health care marketplaces and raising costs for hard working people across the country.”