The senator from California looked like someone had punched the wind out of her. On an unseasonably cold January 10, the tense first day of hearings about President Donald Trump’s nomination of Jeff Sessions as attorney general, Dianne Feinstein was pallid, with deeper than usual divots beneath her eyes. Instead of one of her trademark colorful jackets, she wore all black. Privately and politically, the previous year had been tough. Her husband had been diagnosed with lung cancer and her onetime Senate colleague Hillary Clinton had lost the battle for the White House to a man Feinstein considered beneath contempt.

That morning, after protesters dressed as Ku Klux Klan members were dragged out of the hearing room, Feinstein first signaled her allegiance to Senate tradition, saying it wasn’t easy to criticize a fellow member of the chamber. But then she laid out a formidable case against the Alabama senator and his history of abetting racism, approving torture, and battling abortion rights. “I am old enough to remember what it was like before” Roe v. Wade, she said, recalling how, as a member of the California Women’s Parole Board in the 1960s, she had sent women to prison for 10-year sentences for terminating pregnancies. “And they still went back to it because the need was so great.” (Sessions, for his part, coldly affirmed that he saw Roe as “one of the worst, colossally erroneous Supreme Court decisions of all time.”)

Feinstein’s committee chair was empty by the time the hearing moved on to questions about the potential connections between Russia and the Trump campaign. She had slipped away for surgery to install a pacemaker—a matter of “some urgency,” she told me. “I had to get it done quickly.”

But it wasn’t just the device in her chest that marked a change of heart for Feinstein when she returned two days later. For decades, the Senate’s most senior member had styled herself as the ultimate pragmatist, a veteran deal-maker willing to collaborate with Republicans to get things done. As she assured me in February, in one of half a dozen conversations we had over the past year, ideologically she saw herself as neither right nor left, but focused merely on “whether it’s right or wrong. That’s all.”

Now she faced a different challenge—a president whose election was, she had come to believe, in itself wrong. During the campaign, Feinstein, as the ranking Democratic member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, was one of the Gang of Eight members of Congress who receive classified national security briefings. In September, that group was told that the intelligence agencies had concluded that Russia was trying to interfere with the election in order to help Trump. Feinstein and her House counterpart, Rep. Adam Schiff, issued a startling joint public statement demanding that Vladimir Putin “immediately order a halt to this activity.”

In our conversations, Feinstein fumed that the Obama administration had been too cautious in keeping vital information on this interference—which she still cannot legally disclose—under wraps. They “should have been more forward-leaning and let people know what was going on before the election,” she told me. Had the public known what she knew, Feinstein insists, it would have changed the outcome. “I deeply do believe it.” Now, the Senate Intelligence Committee she once led is in charge of investigating the Russia connection—but, she warns, with insufficient resources and focus. Only 7 Senate staffers are assigned to the Russia probe; the 2014 Benghazi investigation in the House had 46. The committee’s Republican chairman, Sen. Richard Burr (R-N.C.), has reportedly refused to sign key requests for information, such as documents from the Trump campaign.

Feinstein turned 83 last summer. Her hair is still thick, her blue eyes penetrating, the toll of the years apparent in just a bit of unsteadiness in the knees. She is charming enough to often get people to say “yes” without asking. But, says one of her admirers, former CIA Director Leon Panetta, “if she suspects you’re not telling her the whole story, then she’ll become your enemy.”

People who know Feinstein say the election has been transformative for her. “Trump injects an entirely new level of outrage,” Orville Schell, director of the Center on US-China Relations at the Asia Society and a longtime Feinstein friend, told me. With the president going after institutions that Feinstein has historically been aligned with—chief among them the intelligence establishment—Schell believes she will find a middle-of-the-road position increasingly untenable.

“Dianne is like the canary in the mine shaft,” he says. “The last bastion of bridge building in the Senate may be giving up.”

But burning a few bridges may also be the only way for Feinstein to survive politically. Nearly a quarter century into her Senate career, she has remained popular with voters, who reelected her in 2012 with a 62.5 percent majority. But progressive Democrats have been frustrated with her old-school style and steadfast defense of the security state. David Talbot, the founder of Salon and a columnist with the San Francisco Chronicle, told me he sees Feinstein as part of a Washington establishment that kept the nation in the permanent grip of a “war-surveillance state and at the service of the 1 percent.” (The senator calls this “nonsense.”)

More recently, Feinstein has found herself in the sights of a resistance movement with little patience for the status quo. Amid the chaos unleashed by Trump’s January travel ban, protesters picketed her Santa Monica field office and her San Francisco mansion. They demanded she vote no on Sessions, with some carrying signs: “Primary Feinstein if she’s not more aggressive!” At a San Francisco town hall in April, she faced both cheers and boos.

Initially, she brushed it off. “These are very small demonstrations,” she told me. “I’ve lived through big riots. I’ve lived through the torching of 12 squad cars. I’ve lived through assassinations. These have been very polite and not a problem.”

But the criticism grew louder. In February, activists from the Indivisible movement held an “empty-chair town hall meeting” in Oakland, where a portrait of Feinstein sat onstage as constituents lined up at a microphone to ask questions. Some 700 people attended, and many of the questions dealt with how strong a stand Feinstein would take to resist Trump. “What kind of a legacy do you want to leave?” asked a young woman as the crowd roared approval.

“This is a different Republican Party,” said Amelia Cass, the 34-year-old main organizer of the event. “We see no reason to compromise with these people.” A similar sentiment was in evidence in April at the town hall in San Francisco, where Feinstein herself took questions from enraged constituents.

The roots of the tension in Feinstein’s career—the fighter versus the compromiser—may lie in her childhood on a cul-de-sac of mansions in San Francisco’s exclusive Pacific Heights neighborhood. Feinstein describes her mother, Betty Goldman, in glowing terms. She was a beautiful Russian immigrant whose family had fled St. Petersburg during the revolution. By the time she met Dianne’s father, Dr. Leon Goldman, the first Jewish full professor at the University of California-San Francisco medical school, she was a model for a couture store. “She looked very Garboesque,” Feinstein says.

But Feinstein’s middle sister, Yvonne Banks, told me their mother was given to unpredictable moods. “If she was braiding our hair and the rubber band broke or the ribbons weren’t found, then it was like a major explosion—a total loss of control. She would hit you, pull your hair…There’s one picture where Dianne and I both have tears in our eyes. It was a really formal portrait.” Betty would occasionally lock Dianne out of the house, forcing her to sleep in the family car.

It was only in the late 1970s, when CT scans became available, that Betty Goldman’s brain could be studied. Parts of it, it turned out, had atrophied, possibly because of complications from a severe illness as a child. “Judgment, reason—those were the facilities that she lost,” Feinstein says. “She could always put herself together into a very beautiful woman and play the role, but you couldn’t reason with her.”

Feinstein had her own struggles. In elementary school, “my lowest grade was self-control.” Her eighth-grade teacher directed her to a private Catholic high school, Convent of the Sacred Heart, where she finally felt at home “because I learned discipline,” she said. She sat through doctrinal classes and felt they helped answer the big questions. Today, while she is not a formally observant Jew, she told me, “I am religious in my thinking.”

A year after graduating from Stanford in 1955, the 23-year-old Dianne eloped with attorney Jack Berman. “This was Dianne’s way out,” said her sister, laughing. When the telegram announcing their marriage came from—was it Reno or Mexico?—there was “a firestorm” in the Goldman home. It turned out to be an ill-fated match. Dianne’s husband expected her to devote herself to the household once their daughter, Katherine, was born in 1957. The marriage ended three years later.

After a year and a half as a single mother, Feinstein was not easily won over when Dr. Bert Feinstein asked her out in late 1961. He picked her up for their first dinner in a battered Chevrolet with holes in the upholstery. (It turned out he owned a Rolls, a Bugatti, and an Aston Martin, but the Chevy was the car he’d park on the street.) Nineteen years her senior, the neurosurgeon was so smitten he proposed marriage over coffee. “You’re all I need!” she said sarcastically before walking out of the restaurant alone. It took another year for Feinstein to convince Dianne to marry him. But after that, “my mother and Bert were rarely ever in separate rooms,” recalls Katherine Feinstein, a former San Francisco Superior Court judge.

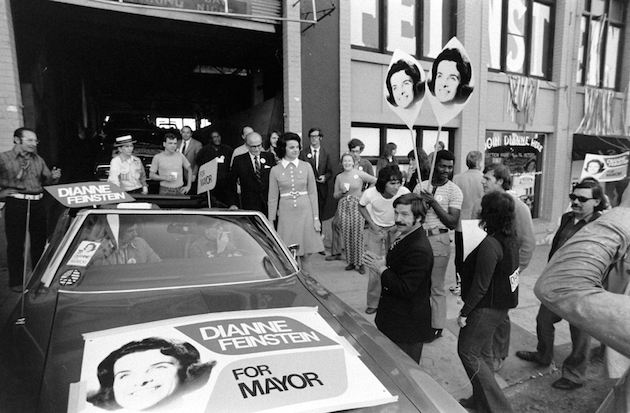

In 1969, Feinstein won a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. She ran for mayor twice and was twice rebuffed, sometimes ridiculed as too prim and proper for what had become the capital of the counterculture. Still, in 1978 she was chosen as president of the Board of Supervisors, accumulating power and setting her own agenda.

But in a life that seemed finally secure, crisis would again invade. After 13 years of marriage, Bert Feinstein one day dropped the news that he had colon cancer, which he fought for two years before his death in 1978.

And Feinstein came to know terrorism up close when a bomb was placed in a flower box at her home. “My husband was sick,” she recalls. “My daughter was in the bedroom right above the street.” The house, under renovation, was wrapped in wood scaffolding. The bomb was set to detonate at 1:30 a.m. Had the night been mild as usual, flames would have engulfed the building in minutes. But a freak drop in temperature caused the explosive to freeze and pop off the detonator. The next morning, Katherine found a package of green gel wrapped in torn plastic with the letters EXPL.

The bombers, thought to be affiliated with the left-wing New World Liberation Front, weren’t caught. But the attack changed Feinstein. “She’d always been law and order,” says Charlotte Shultz, the wife of former Secretary of State George Shultz and a friend of Feinstein’s. Being a target of terrorists, Shultz says, turned her into a full-blown hawk.

In the spring of 2016, with the presidential primaries well underway, I met Feinstein and her third husband, the investor Richard Blum, at Villa Taverna, a private lunch club near Feinstein’s office off Market Street in San Francisco. On the ride over, the senator was incensed by heavy traffic and directed an aide to call the Board of Supervisors. The aide informed her, gently, that this particular road was under the state’s authority, not the city’s, and she grudgingly relented. “That’s why we still call her Mayor Feinstein,” Supervisor Aaron Peskin told me when I related the incident to him. “She takes San Francisco’s day-to-day management about as seriously as her work on the Intelligence Committee.”

Blum is a tall, taut, self-made multimillionaire investor and philanthropist. (It’s in part thanks to their marriage that Feinstein is the Senate’s second-wealthiest member, with an estimated net worth of at least $49 million; his many investments, including in defense contractors, have led critics to charge Feinstein with conflicts of interest.) They met over a business lunch a year before the death of Bert Feinstein—an encounter that impressed neither of them. But after Bert’s death, Blum, recently divorced, asked Dianne to go to dinner during a break from a tedious supervisors meeting.

Blum drove her to Sausalito, he told me, and when their conversation lingered beyond dessert, he drove her on to the No Name Club. She interrupts: “It was the No Name Bar.” Blum, an outdoorsman who routinely ran 50 miles a week, mentioned that he was about to go trekking in the Himalayas, and would she like to come? Feinstein stunned him by saying yes.

The trip turned out to be a disaster for Feinstein, who came down with dysentery. “I went out on the back of a yak, and I said to Dick, ‘Get me out of here and we never have to see each other again.'”

On their return to San Francisco, together, Feinstein took to her bed for a week of recovery. She had been preparing for another mayoral run the following year, but her confidence was weakened from being sick and isolated. Then, on November 27, 1978, she told a reporter she was getting ready to drop out and give up politics for good. Blum drove her to City Hall. Less than two hours later, his phone rang. It was Feinstein. “The mayor has been shot and killed,” she said. “Supervisor Milk has been shot and killed. We think Dan White did it. Please come quickly.”

It was Feinstein who first heard the gunshots and rushed into the office just feet from hers to find Harvey Milk, the popular, openly gay city supervisor, with five bullet wounds in his head, chest, and wrist. Feinstein pressed her finger to the bullet hole on his wrist. There was no pulse. “When someone’s dead,” the doctor’s daughter says, “you know right away.”

Two hours later, Feinstein stepped before a gaggle of reporters in a City Hall corridor and said, “As president of the Board of Supervisors, it’s my duty to make this announcement: Both Mayor Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk have been shot and killed.” She paused a good 10 seconds before the shouting subsided. “The suspect is Supervisor Dan White.” Within a week, Feinstein was appointed mayor of a city shaken to its core. Through all of it, Blum says, “I never sensed her being terrorized. Ever. In fact, she often does her best when the times get the toughest.” (When I told Blum that I’d heard one of Feinstein’s congressional colleagues refer to her as the “Mother Lion,” he laughed: “Well, it wouldn’t be Mother Pussycat.”)

This past August, I was on the phone talking to Feinstein about Clinton’s presidential bid when we were interrupted by a call from Blum. “He’s all agitated,” she whispered when she got back on the line. “Do you know what Trump said today? ‘If she wins, take up arms. It’ll be civil war.'”

Her communications director jumped in. “That’s not exactly what he said. It basically was, ‘If Hillary wins, there’s nothing we can do to prevent her from appointing Supreme Court judges.’ Then he said, ‘Oh, but maybe there’s something that Second Amendment supporters can do.'”

“It may be code,” Feinstein said slowly. “It may be subject to different interpretations. But those that want to interpret it as urging them to do something [violent] will interpret it that way. That’s why people cannot talk this way in the public arena. That’s what I learned.”

After a failed 1990 bid for governor, Feinstein set her sights on the US Senate. As she campaigned in November 1991, an African American law professor named Anita Hill endured a show trial before the Senate Judiciary Committee—then helmed by Joe Biden—over her sexual-harassment allegations against Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas. Hill was publicly humiliated for testifying against Thomas, with Biden forcing her to repeat over and over the most lurid elements of Thomas’ alleged abuse, including his nickname for his penis.

Feinstein watched those hearings on television, noting that all the committee members were men. “I remember thinking how a woman would never belittle someone brave enough to step forward and testify like Anita Hill did,” she has said. “It was a shameful episode.” When Bill Clinton won the White House in 1992, five Democratic women were swept into the Senate, including Feinstein and Barbara Boxer, California’s first female senators. Bill Carrick, a political consultant who has long worked with Feinstein, remembers an elderly man who burst into a polling place saying, “I want to vote for the two girls and the bubba.”

Barely two years into her tenure, Feinstein scored a legislative coup. When she introduced a measure to ban assault weapons, Biden—still chairman of the Judiciary Committee—laughed at her: “‘You’re a freshman. Wait until you see the gunners here.'” But Feinstein managed to get her amendment attached to Biden’s crime bill, and it narrowly passed in 1994. (Ten years later, when the law expired, Feinstein’s attempts to secure reauthorization were blocked by the gun lobby.)

In 2003, Feinstein had a watershed moment of a different sort: She bought into the CIA’s false claims that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. When I asked her how she feels about that today, there was a long pause. “Nobody’s asked me that question,” she said. “I don’t know how to answer it. It just happened that the intelligence was bad.”

The Bush administration had failed to provide conclusive evidence for the WMD claim. But, she told me with a tinge of bitterness, “I took the CIA’s view” and chose to believe them. “That was wrong, and that was an outstanding example to me that you can’t do things always based on intelligence.”

She paused. “It is the decision I regret most,” she said, “and I have to live with it.”

Perhaps fittingly, the single biggest project of Feinstein’s Senate career would turn out to be a massive investigation she pursued from 2009 to 2014 of the CIA’s use of torture. It concluded that the agency, under President George W. Bush, had illegally approved “enhanced interrogation” methods including deprivation of food, drink, and medical care, as well as waterboarding, sexual humiliation, and confinement in coffinlike boxes. Her report, based on 6 million pages of documents, found that none of this succeeded in extracting information that could avert future terrorist attacks.

The torture investigation put Feinstein at odds, sometimes dramatically, with the allies she had cultivated in the national security establishment. CIA chief John Brennan tried to shut down her investigation and threatened her with criminal charges. The agency penetrated her staff’s computer network and accused them of stealing copies of the CIA’s own torture investigation. When Feinstein’s report was done, President Barack Obama handed it to the CIA to be redacted—ignoring her appeals about the obvious conflict of interest.

Feinstein sent copies of her report to several government agencies. But when she lost the chairmanship of the Intelligence Committee following the 2014 midterms, the committee’s new chair, Sen. Richard Burr (R-N.C.), requested that members and agencies return the report so that it would not be subject to Freedom of Information Act requests from the public. Feinstein published an unclassified version on her Senate website, where it can still be found.

Feinstein wasn’t just pursuing the Bush administration’s intelligence failings. She also battled the Obama White House, which in her view mischaracterized and underplayed intelligence about the threat posed by ISIS. In 2015, she boldly contradicted Obama’s claim that the Islamic State was “contained,” telling MSNBC that she had “never been more concerned” about a national security threat.

A few months after that statement, she invited me to lunch in the Senate dining room. The space was nearly empty, it being a Monday and Feinstein being one of the few lawmakers who still spends five days a week in Washington. She ordered Arnold Palmers for both of us. I asked if she had heard from the president about her critique.

“No, I did not,” she replied sharply. “I don’t really believe the White House wanted to know.” She had spoken to a Pentagon whistleblower who had signed a formal complaint and was leading a group of more than 40 intelligence analysts from the US Central Command arguing that their reports on the rise of ISIS were being watered down by superiors. “I found him credible and passed on his complaint to the inspector general of the Pentagon,” she told me, adding that congressional committees were promised a report—but it never came.

“The tradecraft is deception,” Feinstein said wearily when I asked if she believed the intelligence agencies could be held accountable. “The code is brotherhood.”

Karen Greenberg, a law professor at Fordham University and the author of Rogue Justice: The Making of the Security State, says the fights over torture and ISIS were extremely significant for Feinstein. “If you’re in her position and you don’t trust the CIA,” Greenberg says, “it’s destructive on a level that is hard to imagine.”

Two days after her pacemaker surgery, Feinstein turned up for Mike Pompeo’s confirmation hearing at 9 a.m.

As a congressman, Pompeo had been among the Republicans who brutally attacked Feinstein’s torture investigation. “Senator Feinstein has put American lives at risk,” he said at the time. “Our military and our intelligence warriors are heroes, not pawns in some liberal game being played by the ACLU and Senator Feinstein…Her release of the report is the result of a narcissistic self-cleansing.”

In open session, Feinstein pointedly noted that Pompeo had apologized before the hearing, and she was unctuous in her forgiveness. “I really do appreciate your apology. I take it with the sincerity with which you gave it.”

When it was time to vote on Pompeo, she smilingly narrated into the record the concessions she had extracted from the nominee. “I want to make clear that Congressman Pompeo has committed to following the law with respect to torture. He committed…to refuse any orders to restart the CIA’s use of enhanced interrogation techniques that fall outside of the Army Field Manual.” Those Army rules, rewritten by Feinstein and Sen. John McCain, specifically prohibit waterboarding and other forms of torture.

While Feinstein’s “yes” vote on Pompeo drew attacks from progressives, her defenders say she extracted what concessions she could. “He has given me his absolute word, on torture, that he will never permit it to happen again,” she told me later. “And I will be here, and I will hold him to that.”

The following week, Feinstein was back in a committee room considering the Sessions nomination and remembering the Anita Hill hearings. Women, she announced when it came her turn to speak, “have had to fight for everything we have won throughout history.”

A few days earlier, millions of women had taken to the streets around the country—a moment that had made a deep impression on Feinstein, who met with several delegations that day. “They shared an elation and commitment that I’ve never seen before,” Feinstein said. “It was really palpable.”

Had the demonstrators inspired Feinstein to stiffen her own spine? She didn’t respond when I asked her that. But a week later, she was a “no” on Sessions—a highly uncharacteristic vote against the nomination of a fellow senator.

But if Trump has awakened the lioness of the Senate, her roar at first was subdued. As the new administration was roiled by scandal after scandal, Feinstein’s California constituents were blowing up her Twitter feed, demanding that she do everything in her power to push the Russia investigation and block Trump’s nomination of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court. Yet Feinstein remained guarded. She rarely talked to the press and, despite our numerous conversations over the prior year, refused to answer my written questions.

Behind the scenes, though, she buckled down. Ahead of the Gorsuch hearings, Feinstein spent her weekend poring over the judge’s record with the help of her daughter, the retired judge, and in her opening statement she pulled no punches. “This is personal,” she said, her voice thickening with emotion as she pointed out that Gorsuch has argued that the Constitution should be interpreted as it was understood in 1789, “but I find this originalist judicial philosophy really troubling. At the time of our founding, African Americans were enslaved. It was not so long after women had been burned at the stake for witchcraft. The idea of an automobile, let alone the internet, was unfathomable.”

By this time, in March, Feinstein had revived her proposal for “an independent criminal investigation into Russian influence”—i.e., a special prosecutor to look into the political and financial interconnections between Trump, his associates, and Russian officials, oligarchs, and cyberwarriors. She had once indicated to me that she felt compelled to be cautious in what she said on national security because the intelligence community was looking to “get back” at her for the torture report. But after months of stonewalling from the FBI, she and the Republican chair of the Judiciary Committee, Sen. Chuck Grassley, sent what she described as a “tough” letter to FBI Director James Comey, demanding that he stop ducking their requests for a briefing on the Trump-Russia question.

They finally got their briefing on March 15, in a secure Senate basement room. When Feinstein emerged after several hours, she looked shaken. The FBI, as the public would learn a few days later when Comey testified before a House committee, had been investigating since July whether the president and his associates had colluded with Russia to influence the US election.

Feinstein was stopped by reporters. Lips tightly retracted, she said, “This briefing was all on sensitive matters and highly classified,” emphasizing the words with a raise of her eyebrows as Grassley looked on. “It’s really not anything that we can answer questions about.” She looked as determined, to those who knew her, as she had decades earlier in San Francisco, when she stepped up to announce the worst to a city in chaos.

Feinstein was in a lighter mood a couple of days later when activists confronted her outside a Los Angeles fundraiser. She cheerfully stepped into the group as they peppered her with questions, including one about Trump: “There are so many things he is doing that are unconstitutional. How are we going to get him out?”

Feinstein gave a slight smile. “We have a lot of people looking at this,” she said, referring to conflict-of-interest legislation in the works. “I think he’s going to get himself out.”

Additional reporting by Matt Tinoco.