Walter Scott’s cellphone bill was current. In that small but not unimportant aspect of life, he was on solid ground. He had checked in with his elderly parents, called and texted friends. At 50 years old, Scott was a forklift driver, a dominoes aficionado, an extrovert with a buttery voice who sang soul music at social gatherings and spirituals in church. As a young man he’d served in the Coast Guard, but he was discharged after testing positive for marijuana. He drifted between jobs, earned a two-year degree at a technical college, and performed the national anthem at his commencement ceremony. He had four children from two past relationships and was chronically behind on support payments.

On the morning of April 4, 2015, Scott was driving a 1991 Mercedes sedan that he had agreed to purchase from a neighbor, though the paperwork had not yet been squared away. He had a friend with him. He was less than a mile from the home he shared with his girlfriend in North Charleston, South Carolina—genteel Charleston’s poor cousin, a city of roughly 108,000 people that is bisected by railroad tracks and dotted with pawn shops and payday loan outlets. In parts of North Charleston, it seems like just about anything of value—tire superstores, small industrial sites, even residences—is protected by high cyclone fences and barbed wire.

Police Shootings Won’t Stop Unless We Also Stop Shaking Down Black People

At about 9:30 a.m., a police cruiser pulled up behind Scott, lights flashing. Scott made an immediate left turn, then came to a stop in the parking lot of an auto-parts store and watched through the rearview mirror as an officer, dressed in shirt sleeves on that warm spring day, walked toward him. Patrolman Michael Slager, then 33, had his hands at his hips, his right one close to his gun. Also a Coast Guard veteran, and in his fifth year on the force, Slager had moved from out of state to a place where he had no history and few associations. He was an armed white man hired to police unfamiliar black streets. He had gone through nine weeks of training at the South Carolina Criminal Justice Academy—nine, as opposed to the 26 weeks required for a New York City cop. Officers in Europe are typically trained for a year or more.

“The reason for the stop is your third brake light’s out,” Slager said through the driver’s side window. It was the classic DWB (driving while black) rationale for a stop, but Scott knew he had a bigger problem. He was $18,104 in arrears on child support and there was a warrant out for his arrest. Scott had been to jail in the past for failure to pay support. It had cost him jobs and made his debt ever larger and harder to manage. He handed over his license and told Slager he planned to complete the purchase of the car in a couple of days. The interaction was entirely respectful. Scott said he had no registration or insurance card with him. “I’m sorry about that,” he said.

“Okay, but you’re buying the car?”

“Yes, sir.”

The officer returned to his cruiser intending to run Scott’s license through an FBI database, standard procedure. Scott stepped out of his vehicle and then climbed back in when Slager, sitting in his squad car, instructed him to do so. But moments later, Scott got out a second time and ran toward an open field, the site of an abandoned trailer park, and onto a painted asphalt path known locally as the Yellow Brick Road. Slager pursued on foot, warning that he was preparing to fire his stun gun: “Taser! Taser! Taser!” Scott didn’t stop, so Slager hit him with two darts.

The electricity brought Scott to his knees, but he refused to surrender. Slager then “drive-stunned” Scott—put the business end of the Taser directly on him and pulled the trigger—but could not cuff him. The men scuffled on the ground, and a winded Slager pleaded for backup. “One-five-six,” he said into his radio, calling out the badge number of the officer he knew was closest. “Step it up!”

Scott managed to break free and run away in a slow, wobbly gait. This time Slager did not give chase. He unholstered his .45-caliber Glock, took a stance, and put his left hand underneath to steady the weapon. His form was perfect, like in a training video. The only problem was that his gun was aimed at the back of a fleeing man. He squeezed off eight quick shots.

One round grazed Scott’s ear, and four more—hollow-point bullets that expand after impact—ripped into his flesh. One of the bullets entered from the right side of Scott’s back, went through his heart, and lodged just beneath his left nipple, causing massive internal bleeding. Scott fell by the side of a tree and Slager walked 20 or so unhurried steps until he reached the body, at which point he arranged Scott’s arms behind his back and handcuffed a dead or dying man.

From the other side of a fence line, Feidin Santana, a 23-year-old barber and Dominican immigrant who was walking to work, witnessed the chase and began recording on his phone just as Scott broke away from Slager. Of all the police shootings that had been captured by citizens, this one was the most shocking. To many observers, it was unambiguous: An unarmed black man runs. A white cop coldly takes aim, shoots him multiple times in the back, and then appears to plant evidence—the Taser, which Slager had retrieved from where they had scuffled—beside the body.

“I don’t get surprised by much,” says criminologist Philip Stinson, “but that video took my breath away.”

It is customary for police to close ranks around a colleague who is involved in a questionable shooting, but the emergence of Santana’s video three days after the incident made Slager a pariah. North Charleston’s police chief declared himself “sickened.” Slager was fired and charged with murder—a rarity. His first lawyer quit and his union refused to pay for his defense. The city reached a swift civil settlement with Walter Scott’s family and paid out $6.5 million without even being sued. Initially denied bail, Slager spent months in solitary confinement—some of that time in a cell next to Dylann Roof, who murdered nine black parishioners at Charleston’s Mother Emanuel Church two months after Scott’s death.

It seemed as though the whole episode might finally answer the question: What does it take to convict a cop of murder? In early December, however, a jury of 12 citizens said it was unable to reach a consensus about Slager’s guilt or innocence—even on a lesser charge of manslaughter. The judge declared a mistrial, and a new trial date was set for the end of August. But in a surprise development in early May, Slager pleaded guilty to separate federal charges related to the shooting. As part of the plea deal, the state charges will be dropped. Sentencing will take place at a date to be determined. In theory, Slager could face life in prison. In reality, he is likely to get far less.

It was clear, based on courtroom testimony as well as interviews with police trainers and other experts, that Slager had made a series of catastrophic decisions—not just in shooting Scott, but before he ever reached for his weapon. The slaying, its aftermath, and the trial itself would amount to an indictment of his inferior training and of questionable police policies in North Charleston. Several fellow officers, supervisors included, would insist that Slager had done what he was supposed to. He chased a “bad guy,” as one North Charleston cop put it, because that’s what police do. He followed his department’s procedures, and where there were none to guide him, he was led by his own flawed instincts.

Each of the contested police shootings of black men we’ve witnessed in recent years has been a collision of two lives, two life histories. In most cases, they are first and final meetings of two men who would seem to have no other point of intersection. What transpires between them can seem like an accident of fate—wrong place, wrong time—predestined by racial bias and sealed by video footage.

A few months before he shot Walter Scott, Michael Slager had moved to the day shift after several years of working overnight. He sought the change because his wife, Jamie, was pregnant with their first child. She had a son and a daughter from a previous marriage who lived with them and were home-schooled. Slager spent most of his off-hours with his family—going to movies and the mall and attending outdoor events and festivals in Charleston. He liked watching TV comedies and texted his favorite lines to one of his two younger sisters, Madeline Cosenzo. Slager patrolled a sector known as Charleston Farms, the city’s highest-crime area, and his job consisted of driving the same rectangular three-minute loop over and over, 10 hours at a stretch. He told his family he liked the work but emphasized that it was dangerous.

Michael Slager

Jeremy M. Lange

Slager was making about $44,000 a year and money was tight—the couple had to take out a loan for Jamie’s fertility treatments—but he could look forward to a reasonable degree of economic stability. Being a cop is one of the last careers left in America in which a person without a college degree can have job security and robust benefits—good health insurance, paid sick and vacation days, a dedicated pension. Slager drove a department-issued vehicle—a “take-home car,” as the perk is known—which he was allowed to use while off duty. His salary would have eventually reached about $54,000 a year, or more if he rose in rank. It was work that couldn’t be shipped overseas or done by a robot, and a North Charleston cop could make extra money doing private-security gigs. Slager might have retired in his mid-50s, young enough to get another job, and collected pension payments worth more than half his peak salary. He was dutiful, competent, thoroughly average. “He was a very sweet child. He was good. He obeyed,” his mother, Karen Sharpe, told me. “Mike is a person who is very by the book,” his sister said. “He always liked that structure of things.”

Slager had a way of moving through life without leaving a strong impression, good or bad. In the lead-up to the trial, his lawyer, Andrew Savage III, considered making him available for interviews but worried he was so “low affect” that people might wrongly get the impression he was unmoved by Scott’s death. After Feidin Santana’s video went viral, Slager was portrayed in media accounts as having been a troubled child who’d struggled after his parents divorced when he was in his early teens. A story in the New York Times depicted him as a “shy loner” who had a difficult time socializing. “They made it sound like he was some kind of weirdo, which is not true,” his mother said. “He had friends. He was a normal kid.”

Following his parents’ divorce, Slager chose to spend his high school years with his father in New Jersey while his mother and two sisters remained in Florida. He was not much one for sports, nor was he a star student—he was tutored by a school superintendent his father dated (and later married and divorced). Slager gravitated to vocations that put him in uniform. He volunteered with the local rescue squad and was trained as an EMT. After graduation, he took a couple of classes at a community college and then enlisted in the Coast Guard.

For six years he was stationed at a base at Cape Canaveral, Florida. There was a policing component to the job—Slager carried a gun, and on patrol he’d occasionally board suspicious vessels or deal with drunken boaters—but his main assignment was in port. He was what the Coast Guard calls a “fireman,” essentially a boat mechanic. He fixed leaks and changed oil and never rose beyond the rank of E-3, the level to which recruits are elevated after they graduate from boot camp and join their first unit.

Rob Almond, then a petty officer at the Cape Canaveral station, was Slager’s supervisor and also spent time with him socially. Slager was “a great worker,” Almond told me. But he added that it was unusual for a person to serve as long as Slager did without a promotion: “Typically, the Coast Guard does not allow you to extend if you have not made petty officer in four years.” He tried to persuade Slager to pursue the Coast Guard as a career, but “with a promotion comes a move,” and Almond sensed that his friend wanted to remain in Florida near his mother and sisters. In any case, Slager had a different career in mind. “He was passionate about law enforcement,” Almond said. “He had his mind set.”

The Scott family, unlike Slager’s, has deep roots in the Charleston area. They’ve been able to trace their lineage in South Carolina back to the 1800s, though some of their kin almost certainly arrived long before that, likely landing in the 1700s at one of the islands in the harbor—spits of land, now dotted with million-dollar homes, that were once America’s primary slave ports. It is estimated that as many as 400,000 Africans were transported to Charleston in the 1700s and that 40 percent of all present-day African Americans are descended from them. Walter Scott’s ancestors farmed on land outside of Charleston after the Civil War; later generations moved into the city and worked as cooks and domestics. His parents operated a small business that serviced vending machines in commercial buildings. “My father is a go-getter,” Rodney Scott, the youngest of the three Scott brothers, told me. “He always would say to us, ‘Be career-based. If you have one job and you lose it, have the skills to fall back on something else.'”

Rodney is a UPS driver, a licensed funeral director, a “casual longshoreman” (meaning he can get work on the docks when it’s available), and a church organist. The oldest brother, Anthony, is a team leader on an assembly line at a plant that manufactures auto parts, where he has been employed for decades. He has also played the saxophone professionally. Walter, the middle child, was the unsettled one. “He hit a lot of bumps,” Anthony said. “But he didn’t let it depress him. He always kept it moving.”

The Scott family, from left: Rodney, parents Judy and Walter Sr., and Anthony.

Jeremy M. Lange

Like many African American families, the Scott clan hosts regular family reunions with their extended kin—events that usually take place over long weekends in public parks. Walter was not given the responsibility of helping to organize these reunions, but he was the one who would show up early to set up, help cook, and then stay late to pack up the folding chairs and put away the chafing dishes. Once present, he was dependable.

I talked with Rodney and Anthony Scott during breaks in Slager’s trial. They came to court in suits and ties most days and sat with their parents, their jaws set—you could sense their efforts to stay composed. They were forthright about their brother’s flaws. Walter had a GED rather than a high school diploma. He had served only two years in the Coast Guard before his discharge. But when he lost a job, he always managed to find a new one because “he was personable, and he was good at taking tests,” Rodney told me. Not long before his death, Walter was fired from a well-paid warehouse job and then quickly landed similar work via a temp agency. The toxicology tests from his autopsy turned up cocaine in his system. When I asked Anthony if he was surprised by that, he paused for a moment. “Surprised,” he finally answered, “but not shocked.”

The fact that Scott was living in North Charleston worried his loved ones. He had grown up in West Ashley, a middle-class part of neighboring Charleston where his parents still live, as do his brothers and their families. Charleston is about 70 percent white, with a median income of about $55,000, slightly above the national average. North Charleston is less prosperous, with a median income just under $40,000. African Americans make up about 47 percent of the population and Hispanics another 11 percent, while half the city leaders (including the mayor) and about 80 percent of the police force are white. In that way, North Charleston is typical of hundreds of communities across America. Research produced in 2015 by the Center for Public Integrity showed similar racial imbalances, often dramatic ones, between residents and cops in 49 of the nation’s 50 biggest cities.

Walter Scott in his Coast Guard days.

Courtesy of the Scott family

Relations between North Charleston police and the city’s black community have been tense for years. At the time of the shooting, the city’s officers were operating under quotas Slager’s lawyer called “three and three”—meaning they were expected to make three stops of drivers and three of pedestrians on each shift. At one point in 2015, Slager’s sergeant gave him a $10 auto-parts gift certificate for making his numbers. Slager used his Taser more frequently than most of his fellow officers—at least 14 times during his first five years on the force, including twice during one 24-hour period in 2014. (The New York Times calculated that his stun gun use that year accounted for 4 percent of all tasings by a force of 340 officers.)

The three-and-three policy was referred to within the department as “community policing,” a term usually associated with police efforts to get better acquainted with local residents, but few locals regarded the stops as benign. “North Charleston has been known as a very profiled area,” Anthony Scott told me. “You have to drive very carefully through there and make sure everything is correct because there’s always been a dynamic with the police department and black men. It’s nothing to see a black man stopped and the car being searched. There’s other towns around here that are the same way, where you’re very careful, but North Charleston was extreme.”

Walter Scott rose early on the Saturday morning of his death to pick up a work buddy and drive to a nearby church that was giving away food as part of a federally funded program. He was having a barbecue that night, and there were bags of meat and vegetables in the back seat when Slager pulled him over. Sitting in the passenger seat was his friend Pierre Fulton, who paid little attention to the initial exchange between Slager and Scott because he was busy texting with a woman he had met at the food giveaway. Scott’s brothers had to laugh when they found out how Walter had spent the first part of the morning. “We were, like, ‘Our brother was that cheap?'” Rodney said. “He wasn’t indigent and he’s going to get free food?”

There is scant evidence that Scott was a violent man, other than one arrest for assault more than a quarter century ago. He was 5-foot-9, overweight but solidly built. He lifted weights at home. Slager, a trim 6-foot-1 and 17 years Scott’s junior, would testify that he was getting the worst of a fight and had to shoot Scott because he feared for his life. The Scott family vigorously rejects this claim. Walter, they insist, was doing nothing more than trying to wriggle free from the pain of the Taser.

Slager had cuts on his hands and lacerations on his knees after the encounter, fairly minor injuries for a man in a life-and-death struggle. His face was unbruised. “Walter didn’t look like he was in top physical shape, but he could handle himself,” Rodney Scott told me. “If he had really fought Michael Slager, you would have known it. He could’ve beat the living crap out of him.”

A few days before testimony began in Slager’s murder trial, I made the two-hour drive from Charleston to the South Carolina Criminal Justice Academy on the outskirts of the capital city of Columbia. It is a bustling place. The academy produces close to 1,200 new cops each year and sends them out to police departments across the state, with new cadets arriving every three weeks. The barrier to admission is low. Recruits must have a high school diploma or a GED, no felony convictions, no past suggestive of “moral turpitude,” and a good credit history. The course is now 12 weeks rather than the 9 weeks that Slager received—but it is still far short of the national average of about 18 weeks. Trainees here must score 70 out of 100 in most courses to graduate. The passing grade used to be 80, but it was lowered several years ago to ensure there would be enough new cops to meet South Carolina’s needs.

Maria Haberfeld, an expert in police training and the chairwoman of the Department of Law, Police Science and Criminal Justice Administration at John Jay College in New York, was withering in her assessment when we spoke by phone. “South Carolina has one of the worst academies in the country, and that is saying a lot because police training in general is bad,” she said. “Even within the context of how poorly we train, they are an embarrassment to the police profession and a danger to society.”

A report issued in March 2016 by the Police Executive Research Forum argued that misguided training—specifically, instruction that teaches officers to “draw a line in the sand” and resolve confrontations quickly—contributes directly to problematic shootings by police. Cops in training spend a median of 58 hours on firearms proficiency but just 8 hours learning de-escalation tactics to bring episodes to peaceful conclusions, according to PERF’s research. The mechanics of firing a weapon are usually taught separately from the question of when to use it. The report called for “integrated training that combines these related topics in scenario-based sessions. Officers should be trained to consider all of their options in realistic exercises that mirror” what they will encounter on the street.

Training for career officers is similarly gun-centric. Cops in North Charleston and elsewhere must requalify annually at the firing range, but ongoing education in other areas is minimal for officers who are not on SWAT teams or other specialized units. Chuck Wexler is the executive director of PERF, whose membership includes top police brass from around the nation. “You get what the training is,” he told me. “We’re not saying you don’t need the firearms training…But it’s skewed toward the firearm.”

The teaching of de-escalation is also sometimes called scenario training or stress training. The idea is to put officers in settings that feel as realistic as possible and train them to respond with a sense of calm and, most importantly, to slow things down when faced with a potentially explosive situation. This is difficult, because cops on the street sometimes act out of fear—and they often have good reason to be fearful. “It takes time,” Haberfeld said. “You’re changing the way a person thinks, how he deals with pressure and stress.”

The academy campus consists of buildings and training areas scattered over a 300-acre property neighbored by a state forest, a juvenile detention facility, and an adult prison. The cadets dress in khakis and carry holstered guns. They walk from class to class in formation. Florence McCants, the academy’s public information officer, gives me a tour, and we stop to observe some of the instruction. In one session, held near an outdoor driving course, the trainees take turns approaching vehicles driven by instructors posing as noncooperative subjects. One driver, stopped for running a red light, hands the cadet a lawyer’s business card and bellows, “Call him! I ain’t talkin’ to you. I know how y’all treat people around here.” He won’t hand over his driver’s license and he refuses to get out of the car when ordered to do so. In another scenario, the instructor mimes putting a knife to his own throat and threatens to kill himself. In each case, the trainees visibly struggle. They are flummoxed and unsure of how to resolve the situation peacefully.

Car stops are the bread-and-butter work of patrol officers. Most are routine, but the ones that aren’t put police to the test. Some suspects turn violent. Others, like Walter Scott, run away. This is the kind of training scenario that experts believe every cop should be put through dozens or perhaps even hundreds of times, but these cadets will experience it just three or four. The irony is that the academy is funded by fines and fees, with $5 from every ticket directed toward teaching future cops. Because the number of tickets varies from one year to the next, administrators cannot easily predict how much money they will have at their disposal. “We train what we can afford to train,” McCants told me.

I did not come away from my day at the academy with a wholly negative impression. Much of what I observed seemed thoughtful—there was just too little of it. Administrators told me that in recent years, dating back to the shooting of Michael Brown by a policeman in Ferguson, Missouri, instruction had moved more in the direction of de-escalation and away from the traditional pedagogy that police must always stay “one level of force” above a noncompliant suspect. The force spectrum begins with an officer’s mere presence on the scene, followed by verbal commands and “empty hand” control (physical restraint). Next comes the deployment of pepper spray, a baton, or a Taser—and finally, if all else fails, a service weapon. Once cops resort to their guns, they are trained to aim at “center mass,” as Slager did, to neutralize a threat. The two approaches are not mutually exclusive, but de-escalation is intended to give officers the skills and mindset to avoid using force in the first place.

Before leaving the academy, I wanted to see the obstacle course—for a specific reason. Slager had portrayed himself as a man neither powerful enough to contend with Scott nor fit enough to keep running after him to continue the fight. His weakness was a central element of his defense. Like most police departments, North Charleston’s has no mandatory fitness training. The obstacle course was the only physical test Slager had to master over the course of his law enforcement career.

The 290-yard course is laid out in a gymnasium. It includes a pair of 18-inch-high hurdles, a short set of stairs, and some obstacles a runner must hop over or duck under. A “ditch simulation” is a six-foot jump—one long stride—marked by lines on the floor. The course must be completed in two minutes and six seconds. The only remotely challenging task—the requirement to drag a 150-pound sack 20 feet—is made easier by a slick floor. Except for that, the course could be aced by any reasonably fit 10-year-old.

One of the first things Slager told investigators after the shooting was, “I’m not a real strong guy.” And though no one wants police officers who are quick to resort to physical force, Slager may indeed have been too soft for the job—a patrolman who was assertive about stopping people but whose self-image of weakness led him to reach too quickly for his Taser, and ultimately his gun.

Also read: “Are You Prepared to Kill Somebody?” Meet one of America’s leading police trainers.

Vanish Films

There are about 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States, and they have no standard set of procedures for handling noncompliant suspects. To give but one example, the New York City Police Department barred its officers from shooting at moving vehicles back in 1972, except in cases where the driver or passengers posed a deadly threat. The result was an immediate and sharp decrease in officer-involved shootings—a 33 percent drop the very next year. Yet more than four decades later, many departments still have no formal policy against firing at vehicles, despite the obvious dangers. (In November 2015, police in Marksville, Louisiana, fired on the car of a fleeing suspect, killing his six-year-old son.)

Decisions about when to pursue a suspect on foot are almost always left to the officer’s discretion, and many cops have a hard time resisting. When a suspect runs, “the tendency is to chase,” Wexler said. “There’s a sense that this person must be wanted for something more serious. Why is he running from me?”

Slager had Scott’s ID and his car. He could have waited for backup before he gave chase, or pursued Scott but kept his distance until help arrived. Instead, his actions were guided by his gut, and perhaps informed by the aggressive culture of his workplace. The North Charleston Police Department has no formal policy on when to chase a suspect or whether an officer should do so without backup. At the trial, Slager’s attorney asked one of his commanding officers, Lieutenant Walter Humphries, why Slager could not just have let Scott go and figured out a way to arrest him later. “I suppose that’s always an option, but I’d prefer not to have that officer working for me,” he said. Asked whether the North Charleston police had ever undergone de-escalation training, Humphries replied, “Within the last year or so, there’s been a short video [we were] mandated to watch.”

In January, the Department of Justice issued a report on the improper use of force by police in Chicago, but portions of it could just as well have applied to the Slager case. “We found that officers engage in tactically unsound and unnecessary foot pursuits, and that these foot pursuits too often end with officers unreasonably shooting someone—including unarmed individuals,” the report said. The chases are “inherently dangerous and present substantial risks to officers and the public. Officers may experience fatigue or an adrenaline rush that compromises their ability to control a suspect they capture, to fire their weapons accurately, and even to make sound judgments.”

Michael Slager’s trial began on Halloween day at the Charleston County Courthouse. The building is situated at an intersection known as the Four Corners of Law—the other corners are occupied by a historic Episcopal church, a federal courthouse, and City Hall.

He was represented by Andy Savage, a silver-haired, 69-year-old defense attorney who commands deep respect around Charleston. Savage has defended accused Islamic terrorists along with the usual run of murder and drug suspects. He also represents several of the families whose loved ones were slain by Dylann Roof, who was convicted and sentenced to death in January. Savage took Slager’s case pro bono, he said, because he was incensed that the first lawyer had quit on him. (“I’m not a priest. I’m not a rabbi. I’m a lawyer,” he told the Washington Post.) He hasn’t bothered to tally the hours he and other members of his firm have put into Slager’s defense. If he had billed his client, Savage told me, the total would have come to well over $1 million.

It took just three days for a jury to be seated, and 11 of its 12 members were white—92 percent. Charleston County, from which the jury pool was drawn, is less than 70 percent white. Of the last 75 potential jurors remaining from a larger pool, 16 were black, and Savage used his peremptory challenges to dismiss five of them, along with two Hispanics. A 1968 Supreme Court ruling, Batson v. Kentucky, prohibits the striking of jurors based on their ethnicity, but the rule is easy to circumvent. Savage, responding to objections from the prosecution, gave other reasons for eliminating the minority jurors—one had a poor grasp of English, he said, and another had expressed anti-gun sentiments. When the case is retried, “you could literally end up with a jury that looks exactly the same way,” says Chris Stewart, a civil rights lawyer who represents the Scott family. “The defense will use most of their strikes on minorities. There’s no way to stop it.”

Andy Savage, Slager’s attorney

Jeremy M. Lange

Prosecutor Scarlett Wilson acknowledged in her opening statement that Scott bore at least some responsibility for what happened. “If Walter Scott had stayed in that car, he wouldn’t have been shot,” she said. “If Walter Scott hadn’t resisted arrest he wouldn’t have been shot…He lost his life for his foolishness.” She proceeded to call dozens of witnesses, including Santana, the only one who had seen the chase and the scuffle. And she replayed Santana’s video, as powerful a piece of evidence as a prosecutor could hope for, at least a dozen times for the jury. Most court-watchers felt that Wilson did a competent job, but the room belonged to Savage. He managed to cast doubt on what Santana had observed prior to the start of the video, suggesting that the witness was too far away to see Scott pummel his client. Savage’s investigators also unearthed song lyrics Santana had written that seemed anti-police and used those to try to discredit him.

The case was investigated on the prosecution side by the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division, whose agents had interviewed Slager after the shooting. Savage cross-examined them mercilessly: Why had they not found the bullets that missed Scott? Did they see the hole in a wooden fence that a bullet had made? Did they realize bullets were later found with a metal detector made by the toy company Fisher-Price? They hadn’t initially taken custody of Slager’s duty belt and boots to do forensic tests—why? The Taser was not comprehensively analyzed for DNA—had it been, couldn’t that have proved that Scott had taken control of it?

It did, in fact, seem like the investigators had done a shoddy job at the scene, probably because they had assumed it was a good shooting, not a murder case. There were moments when Savage got on such a roll as he cross-examined the state’s witnesses that I wondered why the prosecution did not object, if only to break his momentum.

A native New Yorker, Savage has spent most of his adult life in South Carolina and now speaks in a quiet rasp with long pauses for effect, like a Southern-inflected Garrison Keillor. In a courthouse corridor one afternoon during a break in the trial, Savage turned to me: “It’s more than about the video, right?” He was asking whether he’d been effective in constructing an alternate narrative and steering the jury away from the state’s most damning evidence. I said yes, I thought he had.

Also read: “None of Us Is Entirely Innocent”: A Timeline of Police Violence and Backlash.

Erik McGregor/Zuma; Cary Edmondson/Reuters; Kevin Terrell/AP

Slager wore the same dark suit every day of the five-week trial. He sat at the defense table next to Savage’s wife, Cheryl, who manages her husband’s trial documents. Slager’s wife and parents sat on the benches behind them, often joined by his sisters. In the same row, behind the prosecution table, sat Scott’s family—parents, brothers, sisters-in-law, and sometimes Walter’s adult children. Both families dressed as if for church. It was chilly in the courtroom, and Walter’s mother—”Miss Judy,” as she is called—often wore a shawl. Several times when the video of the shooting was played, she buried her head on her husband’s shoulder and didn’t watch.

The Black and White Views of Charleston’s Racially Charged Murder Trials

In Charleston, the threads of gentility and brutality run side by side. Gracious architecture and new Southern cooking exist in parallel with the city’s history as a slavery hub. The courtroom was the city in microcosm, divided but at all times civil. Members of the Scott and Slager families greeted each other politely. “I see his mama in the hallway,” Rodney Scott told me. “I say hello. I don’t hate her. I don’t even have hate for Michael Slager. He made a bad decision. Why didn’t he stop? Just stand up and say it: ‘I shot him for no reason.'”

A defendant does not have to testify on his own behalf, and many do not, but Slager took the stand during the fifth week of his trial, shortly after Thanksgiving. His testimony was oddly anticlimactic because his lawyer had already spooled out his story. He was soft. He was afraid. “Speak up a little,” Savage beckoned as he began his questioning. Slager explained that he had planned only to issue Scott a warning about the brake light. He didn’t know why Scott ran, but it never occurred to him not to give chase. He felt in danger as soon as the physical confrontation began. “At that point, I knew Mr. Scott was a lot stronger than me. I knew I was going to lose the fight.”

“In my mind,” he said, “it was total fear.” Scott had grabbed his Taser, he insisted. (In the video, Scott is seen running away from Slager, without the Taser.) “I pulled my firearm and I pulled the trigger,” Slager testified. “I fired until the threat was stopped, like I’m trained to do.”

The cross-examination of Slager was surprisingly short. The whole trial had focused on his actions, but assistant prosecutor Bruce DuRant questioned him for no more than 90 minutes, zeroing in on the numerous elements of his initial comments to investigators that did not square with the video. Slager responded that there were many things he didn’t remember from that day, including retrieving the Taser and dropping it next to Scott’s body—which the prosecution called “staging the scene.” The adrenaline from the fight and the trauma of the shooting had impaired his recollections: “My mind,” he said, “was like spaghetti.”

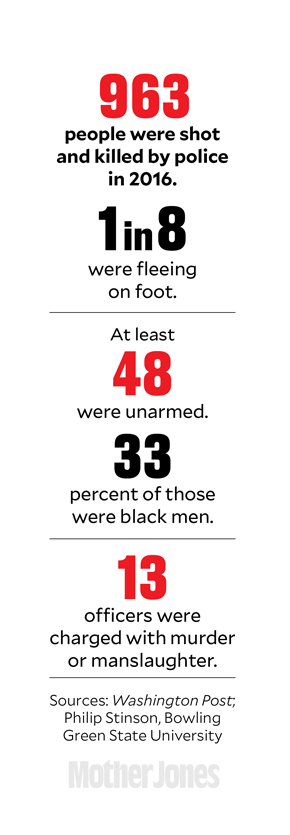

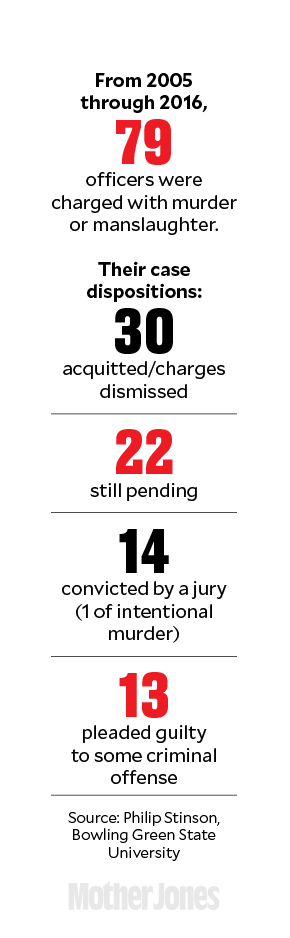

Roughly 1,000 civilians were shot and killed by on-duty police officers in each of the past two years, according to data compiled by the Washington Post and Philip Stinson, a criminologist at Ohio’s Bowling Green State University. The majority had a gun or a knife, but plenty were unarmed. Since 2005, 79 officers have been charged with murder or manslaughter as a result of such shootings, and 27 have been convicted, either by a guilty plea or a jury trial—22 cases are still pending. The convicted officers received an average of just under four years behind bars, Stinson says, although some have gotten as little as a few weeks. Only one officer has been convicted of intentional murder: a Colorado cop who followed an unarmed man into the man’s home, shot him in the back while his mother watched, and then pepper-sprayed him. That officer received a 16-year sentence.

The Slager trial was an example, one among many, of how poorly the legal system functions as a remedy or a deterrent for bad police shootings, which some law enforcement professionals now refer to as “lawful but awful.” The term acknowledges the gap between an avoidable and tragic loss of life and what it takes to convince a jury of 12 citizens to convict a police officer. Stinson, a former cop himself, made his mark in academia by demonstrating how much officers can get away with before they are charged, let alone convicted. “I don’t get surprised by much, but that video took my breath away,” he told me, referring to the Slager footage. “If there was a case you would have expected a conviction, it would have been this one.”

The November election fell on the seventh day of the trial. By the time the proceedings were over, Donald Trump was America’s president-to-be. Andy Savage told me he is “center-left” politically, but his closing argument to a jury dominated by white South Carolinians had a distinctly Trumpian edge. “It’s true. Michael Slager is a white man. Mr. Scott is African American,” Savage told them. But the media was pushing a “false narrative.” His client had unfairly become a “poster boy” for unjust police shootings. He urged the jury to “tell the state of South Carolina, tell the media they have to do their job” by finding Slager not guilty.

A note passed from the jury to the judge during the deliberations seemed to indicate there was just one juror who would not vote to convict, a lone holdout, but the jury foreman and another juror said in interviews later that as many as six jurors were not yet willing to find Slager guilty. The Scott family wanted justice, which to them meant a conviction, but they were not naïve enough to count on one. “He flat-out lied. He sat on the stand and lied. The whole world knows he lied,” said Rodney Scott.

One day toward the end of the trial, I ate lunch with Rodney at a restaurant near the courthouse. “When I drive for UPS, if I see a dog in the street I slam the brakes on,” he told me. “I don’t want to kill a dog. I don’t want to kill a squirrel. I don’t want to kill a possum. How in the world do you shoot [at] him eight times?”

He still couldn’t get over Slager’s ineptness. “I don’t know what was in my brother’s mind,” he said. “But you’ve got his car, his license. You would have had him in 10 minutes. I sit there and I look at him and wonder, ‘Why did you do that? Your family is hurting. My family is hurting. All you had to do was walk away.'”

________

This story was updated to reflect Slager’s guilty plea. On April 19, 2021, an appeals judge upheld Slager’s 20-year prison sentence.