Mother Jones illustration; Getty Images

On an overcast Friday afternoon, Jess Phoenix, a Democratic candidate for Congress from California’s 25th District, was seated at a coffee table made from the hatch of an old ship, in the front room of the Explorers Club on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. A pair of tusks flanked the fireplace in front of her, beyond which, she explained, was the globe on which the ethnologist Thor Heyerdahl plotted his Kon-Tiki expedition to sail the Pacific by raft. The chair by the entrance was a gift from the Empress of Spain. Or maybe it was China. Phoenix, who worked as a volcanologist—think Vesuvius, not Spock—before she decided to run for office, is a member of the club, and she had scheduled a weekend of fundraising and media hits to coincide with its annual dinner.

“It’s a pretty cool place—there’s a lot of history,” Phoenix said. “There’s a whole room upstairs devoted to Teddy Roosevelt and all the stuff that he did on his expeditions. There’s even a sperm whale penis that’s been stuffed and mounted.”

Phoenix is one of four Democrats seeking to make the November ballot in the 25th, a swing seat that stretches from Simi Valley to the edges of the Mojave Desert, where her research and exploration has lately focused. The incumbent Republican, Rep. Steve Knight, survived by 6 percentage points in 2016, but Hillary Clinton carried the area by the same margin—it’s one of seven Republican-held districts in California that voted for the Democratic presidential nominee that year. That means the seat is high on the target lists of state and national Democratic leaders. In the only poll of the race, Phoenix trailed two well-funded Democratic candidates: Bryan Caforio, a lawyer who was the party’s 2016 candidate, and Katie Hill, who runs a nonprofit dedicated to providing housing for the homeless.

But Phoenix does have one big thing working in her favor: She’s the only volcanologist most voters have ever met. So while she hasn’t raised as much money as Caforio and Hill, she’s still managed to collect donations from 6,000 donors across all 50 states, and benefited from a steady diet of free media—a sit-down interview on PBS; features by CBS, NBC, CNN, and the Washington Post. (When reporters are asked if they’d like to drop by Thor Heyerdahl’s place to talk to a lava scientist about the midterms, they tend to at least give it some thought.) In the Trump era, where a candidate in a special election can raise $20 million, and a viral announcement video can make an ironworker into an avatar for a movement, the Resistance has given every candidate the dream of going national—even if, like other such dreams, many will seek it in vain. Phoenix’s story may be unusual, but in 2018 an unusual story is its own kind of blueprint.

The 36-year-old Phoenix lives with her husband—a cybersecurity analyst—and a menagerie of rescue horses, rescue dogs, rescue cats, rescue pigeons, and one (rescued) albino mourning dove on a small farm in the mountains north of Los Angeles. When she is not camped out in Manhattan amid the detritus of Theodore Roosevelt’s vacations, she starts most days by literally shoveling shit. “I tell everybody your day can only get better if it starts with poo,” she says. “But it’s actually really nice—it’s very meditative.”

A sperm whale penis

Tim Murphy / Mother Jones

Politics is the most recent in a series of career changes. After studying history at Smith College, Phoenix took a job as a vet tech but soured on her clients. “[They] would be wearing like a 10-carat diamond ring, and they would say, ‘No, I don’t want to spend $200 to do this lifesaving thing for my dog,’” she said. After considering law school, she chose volcanoes instead. Her work, funded by institutions such as the National Science Foundation and the National Geographic Society, has taken her to every continent except Antarctica. But her focus is in California, where she runs a nonprofit called Blueprint Earth that teaches college students to do field research.* Her last expedition before running for Congress was a cave-mapping trip in the Mojave.

Although earth scientists have hardly made a habit of running for office—there are currently zero in Congress—Phoenix was shaken by Trump’s victory and particularly concerned about what it would mean from an environmental perspective. Trump was poised to open up public lands to extraction industries, pull out of the Paris climate accord, and slash funding for scientific research. So not long after the inauguration, she reached out to 314 Action, a PAC founded in 2016 to boost progressive candidates with STEM backgrounds, about running for office. She sent in a résumé, met with the group, and formally kicked off her campaign that spring.

Not surprisingly, climate change and the environment are front and center in her campaign. Her campaign logo is an image of the Vasquez Rocks, a geologic uplift in the Sierra Pelona mountains at the edge of the 25th. You may remember it from the 1997 volcano flopbuster Dante’s Peak, but more likely, you don’t. Knight is a rare Republican member of the House Science Committee who admits to the reality of climate change, and he’s joined Florida GOP Rep. Carlos Curbelo’s controversial Climate Solutions Caucus. But to Phoenix, he’s a “climate peacock” who wants credit simply for being seen as on the right side—little different in practice from his Republican colleagues who deny the existence of rising temperatures. She notes that when California came up with its own plan to reduce carbon emissions, Knight came out against it.

“It is their position to reject it because their donors require it,” she says. “I mean, on Trump’s application to build that seawall in his golf course in Scotland, the cause listed was sea level rise due to climate change. It’s right there. So I basically I will call BS on any of them who say they don’t believe the science.”

The remainder of Phoenix’s platform is a crash course on where suburban Democrats are at in 2018. She’s calling for free college tuition and gun control, noting that she is not just a member of the Columbine generation, but was living in Littleton at the time of the massacre and dating a student at the school. Like her top two opponents, she also talks up a Medicare-for-all health care plan. Her version is modeled on the Australian system—a position she says is rooted in a scientist’s respect for data.

“True single-payer means that there’s no options for private insurance for anything,” she said. “But in Australia, you can buy what they call ‘extras coverage,’ so if you want, like, above and beyond—if you want to go to specific hospitals or specific extra doctors—you can do that.”

One thing that’s not an issue, at least for now, is impeachment. Phoenix says voters ask her about it all the time, but so far she’s seen nothing that would warrant such a measure. “If Mueller comes up with stuff that’s impeachable, then yes,” she said. “The standards are very, very high. So I’m not gonna jump on board that train and say, ‘Yeah, yeah, impeachment.’ I don’t think there’s any reason to.”

While quick to praise House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.), Phoenix hesitated when asked if she would vote for Pelosi for speaker of the House if she gets to Washington. “We need to make sure we are balancing strong leadership with fresh voices,” she says. “If I got to Congress, I’d want to have a sit-down conversation with her on what sort of leadership she’d be willing to deliver in the road ahead.”

Each of the top three candidates in the district has something going for them. Hill has the support of EMILY’s List, the national organization that backs pro-choice women candidates, and the Victory Fund, which supports LGBT progressives. Caforio has name recognition from his previous campaign and has picked up endorsements from Democracy for America and National Nurses United, two progressive organizations that endorsed Bernie Sanders for president in 2016. And Phoenix is the volcanologist you’ve seen on TV. She has even appeared on Shark Week, for a segment on “devil sharks” who live near underwater volcanoes. (After the porn star Stormy Daniels told 60 Minutes she had once watched Shark Week with Trump, Phoenix tweeted, “You really never know who’s watching those shows, do you?”)

Unlike other swing districts with crowded fields, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee has so far stayed clear of the race ahead of the June 5 primary. “In our primary it’s been pretty good, but I’ve been watching other primaries across the country, particularly what happened in Texas—did you pay attention to the Texas 7th?” she asked me.

In that race, the DCCC went nuclear on another suburban Resistance candidate with an outsized national following, Laura Moser, trashing her as a “Washington insider” because she’d lived in the District of Columbia as a freelance writer while her husband was working in the Obama administration. The attack didn’t work.

“Oh man, that made me sad,” Phoenix said. “That really made me sad. Because it’s kind of a—I just think it’s divisiveness that we don’t need. I’m sure they have their reasons, but I think that it’s not really being true to the process, trying to anoint someone or to disparage someone early. I say this knowing full well it could always turn against me.”

Phoenix, unlike Moser, doesn’t boast a long trove of old writings to pick through, and her residency was never in question. But the Texas race illustrated the pitfalls that sometimes face candidates like her, who have bypassed the traditional gatekeeping process only to find out that establishment organs have other plans. In Kentucky’s 6th Congressional District, fighter pilot Amy McGrath raised $700,000 off her own viral debut, but national Democrats subsequently threw their support behind Lexington Mayor Jim Gray. In races across the country, first-time candidates gripped by Resistance fever have encountered similar, well, resistance.

But Phoenix’s connection to a broader movement—she has more than 50,000 Twitter followers, far more than any other Democrat in the race—is an asset, she believes. While some candidates speak effusively about keeping politics local, Phoenix wants to do the opposite; her success is contingent on making the race as national as possible.

“He’s low-key—he’s not a national name like Steve King or Paul Ryan,” she says of Knight. “So in order to raise his profile enough to get people excited enough to get involved, it’s got to be a national effort. That’s been an issue with previous challengers—they haven’t been able to nationalize it. There’s not enough money just in our community to keep pace with the kind of fundraising he does.”

That national appeal has also made her a magnet for other candidates looking to follow in her footsteps. Candidates in other races often message her for tips on boosting their brand. Some have even asked to swap email lists. A few days after we spoke, the comedian and actor Patton Oswalt was heading to the district to do a fundraiser for Phoenix. They met on Twitter.

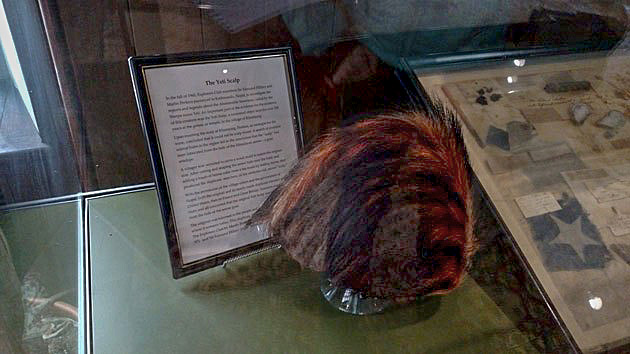

A “Yeti scalp”

Tim Murphy / Mother Jones

After our interview, Phoenix gave me a quick tour of the Explorers Club, easing past a handful of “staff and members only” signs and up four flights of stairs, into the chamber of megafauna formerly known as the Trophy Room. The bustle of activity downstairs was muffled, and the street was quiet below. Stretched out on the beams of the angled ceilings was the pelt of a tiger that, Phoenix explained with a mixture of sadness and awe, suffered from a deformity that forced it to only eat humans. There were mastodon tusks and African masks; a stuffed cheetah; a taxidermied penguin; the head of an onyx; and a coconut-shaped, amber tuft of hair that was identified as a Yeti scalp. She peered in to see who had brought it here. “Oh, Edmund Hillary,” she said. “Of course it was him.” (On further review, the killjoys at the Explorers Club concluded it came from the hide of a Himalayan goat antelope.)

And there, next to the Yeti scalp, was the sperm whale penis. It was curved and cartilaginous, like a white rhinoceros horn.

“It looks nothing like you would think it would look like,” Phoenix said. “If you’re thinking it would look like something.”

Against the wall nearest the door was a painting of a gruff-looking man with a thick beard. “If you actually look at him very closely, he cut his own leg off, so he’s got a peg leg,” she says. What else? “Oh, the narwhal tusk—this is the longest narwhal tusk that’s ever been discovered,” Phoenix said. It was the length of a surfboard and as thick as a baseball bat. As an animal lover, Phoenix is sometimes uncomfortable being in this room, at a club where in just a few hours, at the annual dinner, members would sample a menu including iguana, jellyfish, tarantula, and python. (Phoenix, a vegetarian, tried the durian-fruit empanadas.) “They found that one,” she says of the tusk. “So it’s like, okay! For once, one that they didn’t actually kill!”

Thus concluded the tour.

On our way down to the lobby, as we passed the smiling headshots of astronauts, sailors, and men in pith helmets, Phoenix paused on the landing to gape at a pair of photos. They depicted the same Arctic inlet, taken 100 years apart by two different princes from Monaco named Albert. The first was dominated by a glacier; the second showed only open water. Phoenix gestured with her hand—a chance to get back on message.

“Climate change is real,” she said. “Look at that.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misidentified which kinds of students participate in Blueprint Earth research trips.