Alex Edelman/CNP/AP

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has been slowly loosening federal checks on controversial for-profit colleges, one regulation at a time, since she took office. But her department just took a huge and dangerous leap forward, gutting the team tasked with investigating predatory practices in higher education and effectively squashing several investigations already in progress, according to a New York Times report this past weekend.

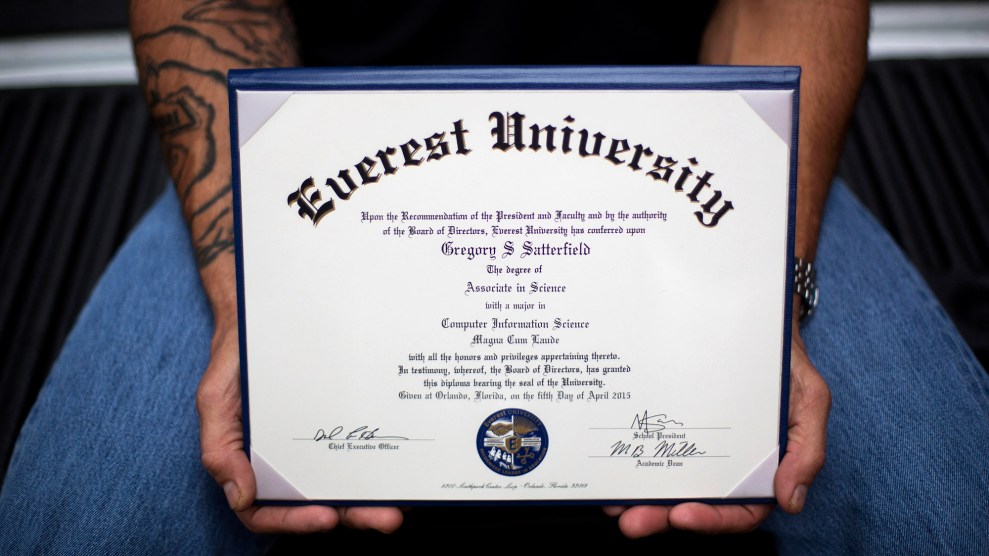

The investigative enforcement unit was formed in February 2016 to investigate fraud and misconduct in public and private colleges and universities a year after an incident with Corinthian Colleges. Once one of the largest for-profit college operators, Corinthian filed for bankruptcy and shut down in the wake of state and federal investigations into its potentially unlawful practices, from falsifying job placement data to inflating graduation rates—leaving students in the lurch.

While the incident with Corinthian Colleges wasn’t the first time for-profit colleges found themselves in hot water—they have been at the center of lawsuits and investigations for years—before 2016, the federal government didn’t have an enforcement unit specifically dedicated to cracking down on predatory practices at colleges and universities.

Now, according to the Times story, protections for students from for-profit colleges are on a steep decline. The investigative unit, which once numbered at about a dozen staffers, has scaled down to just three, and, what’s more, the small team has been relegated to processing loan forgiveness applications and smaller compliance cases. (The umbrella Student Aid Enforcement Unit has four divisions for investigations, processing debt relief claims, administrative actions, and Clery Act compliance.)

Education Department spokeswoman Liz Hill told the Times that the changes came as a result of attrition and noted that sending employees to work on fulfilling forgiveness applications “neither points to a curtailment of our school oversight efforts nor indicates a conscious effort to ignore ‘large-scale’ investigations.”

But since she was sworn in, DeVos has either rolled back or delayed several regulations put into place during the Obama administration on a wide range of issues, and, as I have reported in the past, she has specifically targeted those concerning the accountability of for-profit colleges. For one, DeVos reversed rules that allowed students who attended colleges with a history of fraudulent and deceptive practices to seek debt relief from her department. DeVos also halted the implementation of the gainful employment rule, which allowed the federal government to pull financial aid funds from colleges whose programs failed to meet certain standards. The moves have ultimately been part of a large-scale “regulatory reset” undertaken by DeVos in the name of reining in what she sees as government overreach.

Aaron Ament, a former chief of staff at the Obama Education Department general counsel’s office who helped create the investigative unit, notes that DeVos’ actions are likely to set off changes to the behavior of the institutions the unit was trying to keep in line. Now working with other Obama-administration officials in a new organization, the National Student Legal Defense Network, Ament tells Mother Jones that under Obama, for-profit colleges “saw that there was a new cop on the beat and they would have to shift not just their recruiting practices but the ways they interacted with students and helped them obtain jobs.” For instance, he says, in part because of pressure from the new unit and other Obama-era regulations, a number of schools voluntarily stated that they would stop making students sign mandatory arbitration clauses and that they would limit how much revenue they received from federal student aid. But now, he says, “It’s unexplainable that a department whose mission it is to protect students is appearing to side with predatory for-profit colleges.”

DeVos’ actions and the changes to the investigative team perhaps shouldn’t be surprising when considering the people she has hired; several prominent staffers have come from the for-profit college operators that were under federal investigation. For one, Taylor Hansen, a former lobbyist for for-profit college trade association Career Education Colleges and Universities worked for a month at the department during the Trump transition on its so-called “beachhead” team. DeVos has also brought on Carlos Muniz, a former deputy attorney general under Florida’s Pam Bondi who, as a private attorney, consulted with for-profit college operator Career Education Corp (not to be confused with Career Education Colleges and Universities).

And last March, DeVos tapped as a special assistant Robert Eitel, a former vice president of regulatory legal services at for-profit Bridgepoint Education who had also done work with Career Education Corp. The Times reports that in late 2016, the investigative team was examining recruiting and advertising practices at both institutions. As a special assistant, Eitel took an unpaid leave from Bridgepoint, and then left the company to become DeVos’ senior counselor in April. Since then, Eitel, who worked as deputy general counsel at the Education Department under George W. Bush, has recused himself from matters related to Bridgepoint and Career Education Corp, though he co-chairs a federal task force aimed at scrutinizing department regulations that may be seen as federal government overreach.

Senate Democrats have also scrutinized the February hiring of Diane Auer Jones, a former policy adviser at the department during the Bush years who later became a senior executive at Career Education Corp. In an April letter to DeVos, 10 lawmakers warned that Jones’ close relationship with for-profit colleges as a lobbyist could influence her objectivity in approaching policies surrounding for-profit colleges and raised the possibility of potential “conflicts of interest.” The Times reports that Jones, who serves as DeVos’ senior adviser on postsecondary education, had not recused herself from issues involving Career Education Corp.

Meanwhile, in August 2017, DeVos brought on Julian Schmoke, who previously served as dean of DeVry University, to oversee the investigative unit and three other divisions at the Student Aid Enforcement Unit. An investigation into DeVry, now known as Adtalem Global Education, was launched during the Obama administration for claims of misleading prospective students about their future job prospects. The department reached a limited settlement with DeVry when it couldn’t substantiate a job placement claim, but, according to the Times, the investigative team continued to look into claims against DeVry. Shortly before Schmoke took the job last year, the investigation “ground to a halt”; the Times notes that Schmoke has recused himself from DeVry matters.

Ament, though, hasn’t lost all hope that DeVos will completely unravel the work of his former team. He notes that in the past, the unit partnered with state attorneys general and other federal agencies in investigations into predatory practices and was meant to be apolitical. He now says it will be up to these state officials, local prosecutors, and others to pick up where the federal government leaves off.

So far, attorneys generals have investigated Bridgepoint and Career Education Corp. A Bridgepoint Education SEC filing shows the company faces an investigation in Massachusetts and a lawsuit filed last November by California attorney general Xavier Becerra. Meanwhile, Career Education Corp has received civil investigative requests or subpoenas from attorneys general in 22 states since 2010 regarding “whether the Company and its schools have complied with certain state consumer protection laws,” according to a company’s SEC filing.

“By hiring executives from schools that are under investigation, failing to pursue open investigations, and dismantling this office,” Ament says, “Betsy DeVos is sending a signal that the US Department of Education under her watch is going to turn a blind eye to fraud and relinquish its duties in protecting students.”