Women detainees at Angel Island, where immigrants were processed before being allowed into the country, circa 1910.Courtesy of the California Historical Society.

For about two hours at Oakland Technical High School last winter, Jah-Yee Woo worked with her 11th grade honors US history students to assemble a timeline. On its surface, the activity seemed simple—with students placing small, colorful pieces of paper on a poster. But each piece of paper marked a different immigration policy throughout history, placed above or below the line following student debate over whether the entry was inclusive or exclusive. Inclusive polices fell above the line, exclusionary ones below. On the left of one group’s timeline was a yellow note describing the 1790 Naturalization Act, one of the first laws establishing citizenship, but only for a “free white person.” It was placed below the line. Toward the far right was a photo of President Donald Trump displaying the text of his executive order banning citizens from several Muslim-majority countries. It, too, was below the line. “Exclusive,” one student wrote on a post-it next to Trump’s face.

The exercise was just one part of a larger new curriculum developed by Woo and other teachers in the Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) that’s centered on provocative but increasingly crucial questions as Trump cracks down on immigrants seeking to enter the country: Who gets to be included in America, and why?

The curriculum hinges specifically on an often little-explored slice of history, the Chinese Exclusion Act—an 1882 law that barred all Chinese nationals from entering the United States and from becoming citizens. One of the first pieces of federal legislation to exclude a race and nationality from immigration and citizenship, the law remained in place for more than 60 years. The textbook Woo uses for US history, however, doesn’t explore it very much. “It’s one paragraph,” she says. “It doesn’t really bring to life the stories and struggles of so many members of that community.” So Woo and her peers are turning to archival documents, interviews with experts, and, crucially, a new powerful documentary about the act—The Chinese Exclusion Act, directed by Ric Burns and Li-Shin Yu—that aired nationally on PBS last month to teach a rich history of the law and its effects on the Chinese community.

And while the curriculum and documentary were initially developed before Trump took office, the history’s parallels to today are striking, particularly as Trump’s travel ban becomes settled law. The documentary portrays how politicians used growing anti-immigrant sentiment and nativism to keep the act in place while advancing their own political agendas. The film calls into question the idea that America has always been welcoming to newcomers, tracing how Chinese groups were targeted by discriminatory laws and, in several instances, lynched and driven out of their communities. But it also brings to life how they attempted to resist the laws through hundreds of lawsuits.

“It’s clear we are living in a politically and culturally fractious time, with the very definition of ‘Who is American?’ being contested,” says Stephen Gong, the executive director of the Center for Asian American Media, which co-produced the film.* And, he adds, understanding the history of Chinese exclusion “provides important historical context to this debate…If we don’t tell the history and show how it’s done and what the implications are…you get it repeated.”

The effort first began about a year and a half ago, when the Center for Asian American Media (CAAM) approached the Oakland school district about creating a curriculum specifically around Chinese Exclusion Act. The San Francisco-based nonprofit had already helped facilitate hundreds of community screenings for the film across the country and wanted to make sure it could be accessible to K-12 students. For Elizabeth Humphries, OUSD’s high school history specialist, the request was “an unintentional moment of synergy.” The district had recently gone through a textbook adoption process and, after reviewing many of the materials, knew there were clear gaps it needed to fill in its classes. “There’s still a fairly traditionally dominant narrative that’s being presented,” says Humphries, adding that there was also “a gap in representation of Asian Americans, even in world history classes.”

What’s more, OUSD had increasingly been hearing from its Asian students that they wanted to see themselves reflected in the curriculum. When the district conducted a survey of its ethnic studies students during the 2016-17 school year, it found that students who identified as Asian American, Arab American, or as multi-ethnic were the least likely to say they were learning about their own history and culture. These concerns were echoed again in a recent listening campaign conducted among Asian and Pacific Islander students last fall. “I think our API students have felt invisible and unseen for a really long time, and it absolutely impacts their confidence, their understanding of who they are and their role in the world,” says Lailan Huen, who directs the district’s Asian Pacific Islander Student Achievement Initiative, a targeted support program for the district’s approximately 6,000 API students.

Of course, OUSD isn’t unique in this regard, or the first to recognize the lack of representation in school curricula. Communities of color have long called for their histories to be included in educational contexts, and today, students often learn about these histories in ethnic studies courses, where they examine traditionally underrepresented perspectives. Though ethnic studies is most often taught at the college level, there’s been a growing movement to bring the courses into K-12 classrooms—and even make them a requirement for graduation, including in some school districts in California. Ethnic studies didn’t always have such a welcome reception, though: In 2010, for instance, Arizona lawmakers banned some of the courses outright, claiming they stoked resentment. (A judge eventually blocked the law.)

Studies have shown that ethnic studies courses can generally improve student engagement and increase their sense of agency. A 2016 Stanford study of the San Francisco Unified School District’s ninth-grade ethnic studies curricula found that struggling students who took the courses improved their attendance and academic outcomes. “When you start to include marginalized narratives, particularly of people of color, it tells students, ‘Look these people are also important. We need to know this history. These are our histories,’” Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales, a professor of Asian American studies at San Francisco State University who has worked on developing ethnic studies curricula, says. “When [students of color] don’t see themselves as important and as having value, it stunts their pursuits.”

It’s also important for students to get a chance to critically learn about racism and how it comes about, says Christine Sleeter, a professor emerita at California State University-Monterey Bay who is considered an expert on ethnic studies curriculum. Students, even at a young age, can pick up on racist attitudes around them but don’t often have a good explanation for them. “When schools try to open up questions of racism and exclusion, it can help [students] understand why things are the way they are and how to make things fairer,” says Sleeter.

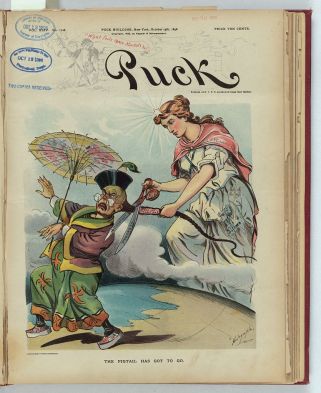

With funding from CAAM, as well as help from the University of California-Berkeley’s History-Social Science Project, the district began developing the Chinese Exclusion Act lessons last summer. The teachers created four modules, each addressing a particular theme or question within the law’s history—one lesson asked students to analyze the anti-Chinese political cartoons in order to understand biases in sources; another delved into how attitudes toward Chinese Americans changed over time.

In another module, students learn about resistance to the Exclusion Act and examine the kinds of tactics, such as within the court system or through protests, that were effective at challenging injustice. One of the cases the students analyze is the Geary Act, a proposal to require Chinese nationals to register and carry identification cards or face arrest and deportation. Community groups banded together to file a legal challenge to the law, and as many as 85,000 Chinese nationals refused to register—one of the largest acts of mass civil disobedience in history.

One of the cartoons the students analyze in the lessons

US Library of Congress

Showing resistance was crucial to the lesson as it “is often the last thing we teach—it’s always about oppression,” says Becca Rozo-Marsh, a teacher at Oakland’s Coliseum College Prep Academy who also helped develop the lesson plans. When Marsh taught the lesson on resistance in her own classroom, where the majority of her students are Latino, she says they were generally engaged and able to draw connections to their own families’ immigrant stories. Many were also surprised to learn that Chinese groups had experienced violence and discrimination. “I think it was important for them to challenge these preconceived notions,” she says, “and to not feel isolated—to know that there are relatable struggles.” She drew connections between some of the survival strategies the Chinese used to try to escape exclusionary laws, such as refusing to register under the Geary Act or forging their identities in order to enter the country, to how communities do so today by using fake Social Security numbers to work and make a living. “There were hundreds of anti-Chinese laws, but there was constant resistance. We want students to think about the Chinese exclusion act as oppressive measures continue—that people continue to resist and survive,” she says.

Woo says she’s been encouraged by how some students have continued to use similar frameworks to analyze other movements—as well as connecting it to their own experiences. One 11th-grade student, who identifies as Asian American and Latinx, told Woo that learning about the resistance strategies “inspired me to think more about using inside and outside tactics in my own life.” Another student who identifies as Latinx told her the activity “gave me insight into how different racial groups were targeted. I always thought it was just Mexicans who were excluded, but I saw how other groups were treated before us.”

She is also optimistic that students can apply the lessons to their own lives, and interrogate how certain policy decisions get made. At the end of the timeline activity, Woo asked students whether they thought the US was moving toward a more inclusive or exclusive period of history. And though some of her students were pessimistic following Trump’s election, she also wanted them to take into account the resistance that was happening today. “Even though our current immigration policy and what’s being proposed is so disheartening, I think seeing that there are ways to fight it [is] important, so students don’t just feel the weight of history, but that they feel the possibility of history,” she says. Woo feels the film is particularly crucial for this deeper level of understanding: “The narrative piece helps with thinking about, ‘Oh, what were people actually thinking and doing. What were their motives?’ And that in turn can help students ask, ‘What are we thinking and doing now about problems that we face in the present?'”

Woo and her peers are hopeful about the success of their curriculum, and with support from CAAM, they’ll present the lessons at a national social studies conference later this summer, with the goal of helping teachers across the country take them into their own classrooms. The finalized plans will be published online on PBS Learning Media later this year.

In the long term, Humphries hopes that OUSD can infuse an ethnic studies approach in the core history classes all students take. “Ethnic studies shouldn’t be the only place where students are seeing their communities or their experiences reflected in the history curriculum, and where students feel supported in their identity,” she says. “How can we bring what is effective about ethnic studies and actually use that to seriously change the way we approach teaching history? I think that’s our charge.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article originally misspelled the name of CAAM’s executive director.