Mother Jones illustration

Wayne Snitzky was 18 years old when he was sentenced to prison for murdering a girl four years his junior. It was 1995, beepers were the height of personal technology, and the most sophisticated video game he had played was “Leisure Suit Larry,” a 2D adult-themed computer game that followed the sexual exploits of the sleazy main character. During the 23 years he has been locked up in Ohio’s Marion Correctional Institute, Snitzky has been on the periphery of technology’s rapid evolution.

While he was able to maintain some of his computer skills through a work program with a nonprofit, where he now teaches other inmates basic tech skills such as composing emails and using a word processor, Snitzky’s access to communication was limited. But in the early 2000s, inmates at Marion got their first taste of email—though a far different version than the one most users know. Inmates received printouts of messages, and wrote their responses on lined paper that would be scanned and sent back for roughly 40 cents each way.

That system was their only option for email until 2014, when prisoners learned Ohio had signed a contract with JPay, a private prison technology service company, for personal tablets. For $140, prisoners would be able to purchase a clear, 7-inch Android device from JPay. The tablets wouldn’t be connected to the internet, but for a fee, Snitzky and his fellow inmates at Marion can access emails, games, and music from their prison cells.

The access comes with a hefty price tag. At Marion, each email Snitzky sends costs 30 cents, and video visits cost nearly $10 for 30 minutes—services that are free for non-incarcerated internet users through services like Google and Skype. In some facilities, a simple game like solitaire that would be free on a phone costs up to $7.99, and movie rentals and purchases range from $2 to $25. These rates are on the cheaper end of the market; in other states, such as Indiana, JPay’s main competitor, GTL, charges 38 cents for an email, up to $7.99 for 48-hour movie rentals, and $24.99 for a monthly music subscription. Even premium versions of streaming services Spotify and Apple Music only cost $9.99 a month for those on the outside, and those plans grant access to millions more songs than what GTL offers.

Ownership of this media can be tenuous. Just this summer, Florida inmates lost about $11.3 million in music downloads after the corrections department switched from JPay to a new contractor. Other inmates report media downloads disappearing from their devices for no explained reason.

Prisons have always been divided by the assistance of families—who can afford commissary food, or who can purchase non-state-issued clothing and necessities. Now, that divide has gone digital, and it’s private contractors and state governments that have benefited from this arrangement. In Ohio, for example, the state makes $1.3 million annually in commissions from JPay services, according to its budget.

The Prison Policy Initiative, a criminal justice and public policy think tank, estimates that each year, families of incarcerated individuals spend upward of $3 billion on goods provided by private companies to prisoners, including technology services. PPI also estimates that up to 72 percent of the prison technology services market, which includes tablets and video visitation, is dominated by just two companies: GTL and Securus, the company that owns JPay.

Both Securus, founded in 1986, and GTL (formerly Global Tel Link), founded in 1989, started off by offering call services in prisons at exorbitant rates. But with the advent of personal technology, the companies have expanded their offerings to personal tablets and Voice over Internet Protocol (VoiP) calls. GTL released its first tablet in 2013. In 2015, its rival, Securus, acquired JPay, a company that had been selling tablets since 2012.

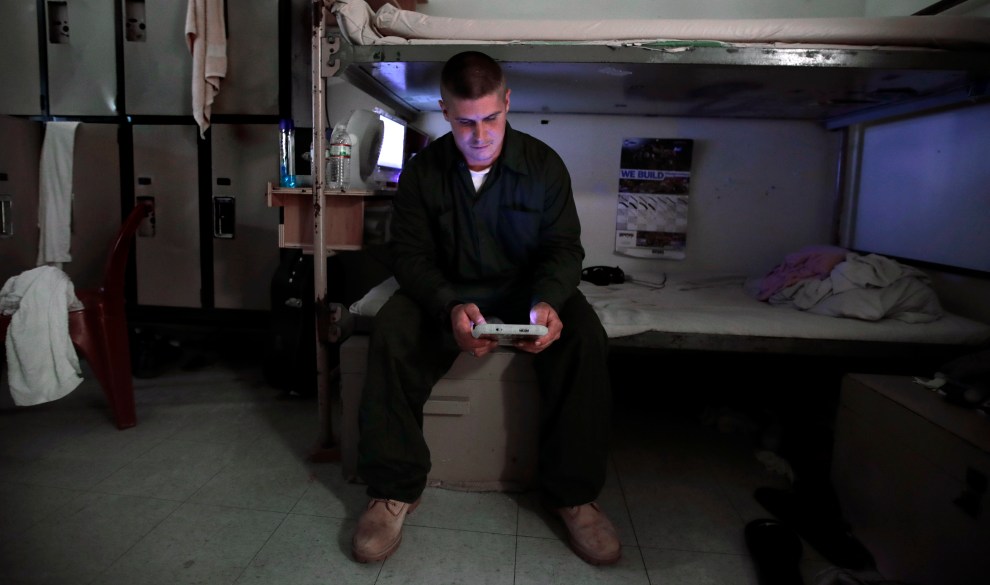

GTL provides tablets that allow inmates to send emails, play games, and video chat with friends and family.

The Idaho Post-Register/ AP

“Most of the money is still in voice minutes,” says Peter Wagner, executive director of PPI. But tablets offer Securus and GTL the opportunity to bundle services and make it more financially taxing for prisons to change technology companies. “[Departments of corrections] see these things as saving money,” he says. “In an industry that uses chains and bars, anything they can do to look kind of cool and modern, they experiment with—but they don’t have a good sense of the costs.”

GTL defends the cost of its services, telling Mother Jones the higher prices account for the extra cost of providing data access, secure hardware, and sturdier devices. “An iPhone off the shelf wouldn’t last a day in these facilities,” said James Lee, a GTL spokesman.

But regulation of these services has not kept pace with their growth. Some states have placed caps on how much companies can charge for phone minutes, for instance, but there are no federal regulations in place to limit how much private companies can charge incarcerated individuals for communications services. After years of rates that sometimes topped $1 a minute, the Federal Communications Commission voted in 2015 to cap rates at 11 cents per minute at federal and state prisons. But the regulation was struck down in court in 2017 after Securus and GTL, among others, challenged the ruling. Under new leadership appointed by President Donald Trump, the FCC has declined to defend the provision in court.

In the interim, the monopolization of prison technological services has only gotten worse. GTL offers tablets to 350,000 inmates across the United States, according to a company representative. According to a JPay representative, there are more than 160,000 JPay tablets currently in use at facilities nationwide. In a 2016 bid proposal from its parent company Securus to the state of Nebraska, JPay stated that it served “more than 1.9 million inmates and released offenders in 34 states” for all of its services, not just tablets.

Currently, a proposed merger between Securus and Inmate Calling Solutions is under FCC review. According to an analysis by PPI, if the merger goes through, Securus would control 54 percent of the prison technology market, GTL would hold 40 percent, and the three other remaining companies would occupy just 1 to 2 percent of the total market share based on revenue share. In a July petition to the FCC, a coalition of eight organizations, including PPI, protested the merger. “In light of numerous public admonishments for violating other Commission rules, policies and procedures, Securus has clearly demonstrated that it lacks the character qualifications to remain a holder of Commission-issued authorizations,” the petitioners stated. For instance, in 2017 the company was fined $1.7 million by the agency for providing “inaccurate and misleading information” in regards to another merger application.

Unlike Ohio, many states provide tablets to prisoners for free, but the transaction costs of using the devices still add up. In New York, which signed a contract with JPay in February to provide 51,000 free tablets to inmates, the only truly free services will be educational products and an undisclosed selection of e-books. While the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision will not collect a commission on the tablets, JPay estimates it will make up to $9 million off inmate purchases in New York by 2020.

Inmate Anthony Plant reads from a tablet at his bunk at the Corrections Transitional Work Center, a low risk security section at the New Hampshire State Prison for Men, in Concord, NH.

Charles Krupa/ AP Photo

All the inmates interviewed for this story said they had relied on family or friends for money transfers, which incur an additional service fee, in order to purchase JPay services. Many worried how they would continue to afford the services on their limited incomes if family members were no longer able to assist them.

“Every time you turn around, it’s another policy that just compromises the strengthening and maintaining of family ties,” says Soffiyah Elijah, executive director of the Alliance of Families for Justice, a nonprofit in New York.

Elijah is concerned tablets could allow states to cut back in-person visitation. In South Dakota, for instance, the state corrections department eliminated one of the country’s last in-person legal assistance programs for prisoners in 2017, replacing it with a free LexisNexis legal search engine. In 2017, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo proposed—though ultimately rescinded—budget cuts that would have reduced visitation days from seven to three days a week at maximum security prisons.

Another hurdle has been technical and customer service problems with the JPay tablets. Mother Jones spoke with half a dozen inmates who experienced technical malfunctions with the tablets on a regular basis. Many recounted malfunctioning apps and customer service requests that went unanswered for months.

But for all their shortcomings in terms of price, tablets can leave inmates better prepared for life after they’ve completed their sentence. “The more you have the real world on your mind, the less you’re concerned with what goes on in here,” says Kevin Light-Roth, 35, who is serving a 28-year sentence in a facility in Washington state for murder. “You don’t release them as a stranger to try to figure things out. I think that’s a massively positive change.”

In Virginia, Matthew Muniz, 34, has been in and out of prison for most of his eight-year-old daughter’s life. Every day, he waits in line with 86 other men for a 20-minute slot at the facility’s only network-connected kiosks to download any new emails and content. Having his own tablet at least allows Muniz to type out his emails in advance. “It helps people stay connected better,” he says, “because the world today isn’t really a pen and paper-type world.”

There’s another bonus: The Virginia Department of Corrections does not allow prisoners to receive direct physical mail, and will only provide them with black and white scans. But since he has a tablet, he can see color pictures of his daughter. The 30 cents per photo add up, but to Muniz, the chance to see his daughter is worth it.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that Pete Wagner said that “Most of the money is still in VoiP.” It has been updated to reflect that he actually said “Most of the money is still in voice minutes.”