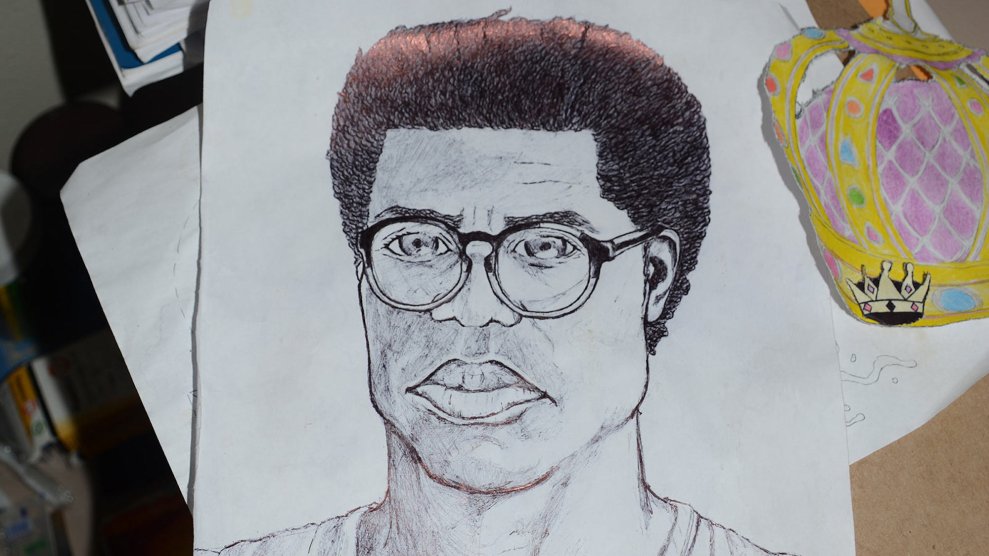

A self-portrait of Jeancarlo Alfonso Jimenez Joseph, who committed suicide in 2017 at a Georgia immigration detention center run by CoreCivic.Georgia Bureau of Investigation

A private prison company worked to block the release of potentially embarrassing information about a suicide at one of its immigration detention centers this summer, according to emails obtained from the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI).

Efrain Romero de la Rosa, a 40-year-old Mexican immigrant diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, committed suicide in July after being held in solitary confinement for three weeks at the Stewart Detention Center in south Georgia. Immigration and Customs Enforcement pays CoreCivic (formerly known as the Corrections Corporation of America) more than $100,000 per day to hold at least 1,600 immigration detainees in Stewart.

After Romero’s death, the GBI, which investigates deaths in Georgia prisons and detention centers, opened an inquiry. Its agents collected video evidence and documents from inside the facility, looking for evidence of foul play. On October 1, as the investigation was coming to a close, a lawyer hired by CoreCivic sent an email to the director of the GBI’s office of privacy and compliance, arguing that a federal regulation barred the agency from publicly releasing any of the findings from its investigation.

“Unlike most prison records with which the GBI ordinarily deals, the further disclosure of records obtained from Stewart…is limited by federal law,” CoreCivic attorney Steve Curry claimed in an email obtained by Mother Jones through a public records request. He cited a post-9/11 federal regulation that grants the Department of Homeland Security control over most information about immigration detainees. “It is our request that there not be a release of information,” he wrote.

CoreCivic’s attempt to block the release of information about Romero’s death came about a year after the GBI released records related to the death of Jeancarlo Alfonso Jimenez Joseph, who committed suicide at Stewart under similar circumstances in May 2017. Jimenez was brought to the United States from Panama when he was 10 years old and grew up in Kansas, eventually earning protection from deportation through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, according to a CNN investigation. But by age 27, he had lost his DACA status following a mental health breakdown. He was struggling with schizophrenia when he was arrested and sent to Stewart, where guards put him in solitary confinement as punishment for what his sister later described as a suicide attempt. After 19 days alone in a cell, he hanged himself.

The GBI’s investigation into Jimenez’s death uncovered embarrassing details about the CoreCivic detention center. Security footage and internal records showed that a guard had falsified logs to conceal that he had not checked on Jimenez at the required 30-minute intervals. The day before Jimenez’s suicide, a volunteer who tried to see about his wellbeing was told that Jimenez couldn’t receive visitors, even though there were no such restrictions in place, according to one report. And earlier in his detention, as Jimenez attempted to fight his deportation case, the detention center failed to send his attorney requested documents.

The guard who falsified logs was fired the month after Jimenez’s suicide, and Stewart’s warden retired soon after the GBI’s investigation was closed. (CoreCivic told journalists the retirement was unrelated to the Jimenez case.)

Details about Jimenez’s death continue to surface, including an account from another detainee who heard Jimenez tell a guard about experiencing psychosis in solitary confinement two weeks before he committed suicide. Meanwhile, Jimenez’ family is suing the federal government to force it to reveal additional information about medical care, incident reports, and inspections at Stewart.

The case, including GBI’s photographs of the cell where Jimenez died, also drew attention to the practice of putting detainees with mental illness in what CoreCivic terms “restrictive housing”—solitary confinement. Experts say solitary confinement can exacerbate suicidal urges and other mental health problems. In 2011, a United Nations special rapporteur on torture recommended banning the use of solitary confinement for any period longer than 15 days.

In his email to the GBI in October, CoreCivic’s lawyer referred to the release of information in Jimenez case. He also cited a federal regulation from 2002, which granted the Department of Homeland Security increased control over information about federal immigration detainees. The regulation was put in place to block an American Civil Liberties Union lawsuit seeking the release of the names, nationalities, and other basic information about Immigration and Naturalization Service detainees held in two New Jersey jails following September 11, 2001.

State and local agencies sometimes use the regulation to deny requests to release records about detained immigrants. Liz Martinez, the advocacy director for Freedom for Immigrants, an anti-detention activist group, says a sheriff’s office in California used the regulation to deny her group’s request for information about ICE detainees’ grievances in a local jail. The Justice Department has also cited the rule in its ongoing lawsuit against California’s sanctuary policies, arguing that a law allowing the state attorney general to inspect ICE detention centers violates the rule.

The regulation is just one of many tactics private prison companies use to block disclosure of government records about their operations. The Freedom of Information Act doesn’t apply to their operation of federal prisons. For more than a decade, Democratic members of Congress have introduced versions of a bill that would force private prisons to follow the same federal disclosure rules as their public counterparts. Private prison companies have lobbied against the bill, which has never gotten out of committee. On the state level, as Mother Jones reported in 2015, CoreCivic has intervened in public records requests to conceal information about lawsuits it has settled involving medical malpractice, wrongful deaths, assaults, and the use of force, arguing that such information “constitutes trade secrets.”

In response to questions about its attorney’s email, CoreCivic public affairs manager Rodney King said it was “standard practice” for the company to urge state agencies to defer decisions about releasing public records to federal authorities. “This matter was investigated by a state agency, GBI, but it occurred in a facility we operate on behalf of a federal government partner, ICE. In these situations, it’s our standard practice to reach out to the state government body to ensure the necessary coordination with the federal government, which has the leadership role in determining how information about an individual in its care is shared,” King said in a statement.

So far, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation has gone along with CoreCivic’s wishes, declining to release its investigative file or answer questions about its conclusions about Romero’s suicide. “The federal statute that prevents the release of these records was not known to the GBI at the time of the Jimenez death investigation and release of records,” said Lisa Harris, the special agent in charge of GBI’s open records unit. “Now that the GBI has knowledge of the statute, we will abide by it.”