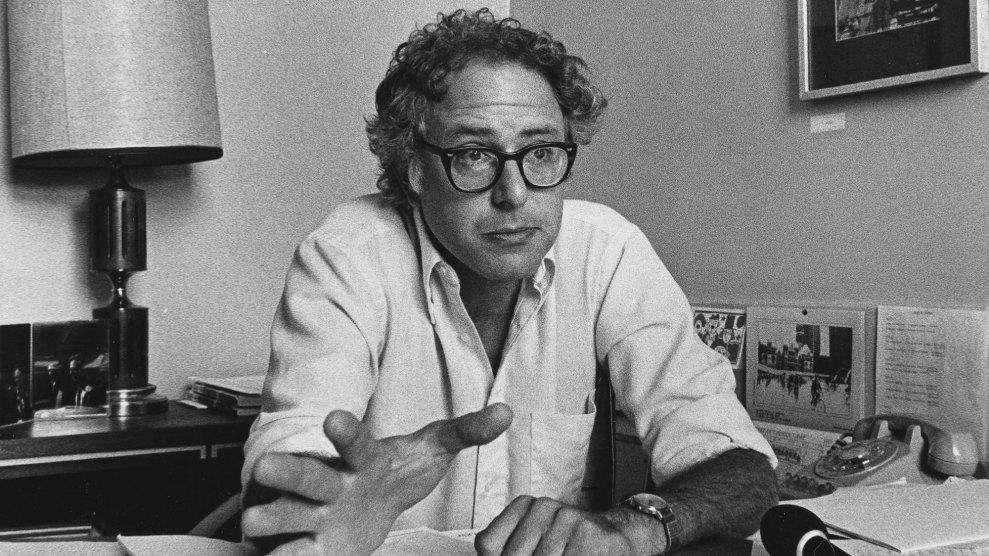

Donna Light/Associated Press

Bernie Sanders launched his second bid for president with about as much pomp as he did his first one. In other words, not much.

In April 2015, Sanders announced his candidacy via Twitter then walked outside his Capitol Hill office and held a press conference. On Monday morning, Sanders got his gritty reboot off the ground in an exclusive interview with Vermont Public Radio. There was no listening tour, no exploratory committee, no “wait and see” teasing—just a bit of personal news and a very successful fundraising email.

But the aesthetics may be the only thing that haven’t changed. After a doomed but hard-fought challenge to Hillary Clinton in 2016, he never really stopped running. He put out books, stumped for candidates, and watched, not impassively, as his proposal for a single-payer health care system was adopted into the Democratic mainstream. Sanders is now a meme and a movement, and he enters the presidential race as something that seemed impossible four years ago—a front-runner for the nomination.

There’s a lot to parse about Sanders and his place in national politics, but if you want to understand what drives him, you have to understand how he got his start. His path to political success, which I traced in a series of 2015 profiles, was riddled with false starts, experimentation, failure, and adaptation. But one moment in particular stood out:

Sometime in the late 1970s, after he’d had a kid, divorced his college sweetheart, lost four elections for statewide offices, and been evicted from his home on Maple Street in Burlington, Vermont, Bernie Sanders moved in with a friend named Richard Sugarman. Sanders, a restless political activist and armchair psychologist with a penchant for arguing his theories late into the night, found a sounding board in the young scholar, who taught philosophy at the nearby University of Vermont. At the time, Sanders was struggling to square his revolutionary zeal with his overwhelming rejection at the polls—and this was reflected in a regular ritual. Many mornings, Sanders would greet his roommate with a simple statement: “We’re not crazy.”

“I’d say, ‘Bernard, maybe the first thing you should say is “Good morning” or something,’” Sugarman recalls. “But he’d say, ‘We’re. Not. Crazy.’”

Sanders has always been driven by righteousness (some would say self-righteousness) about his causes. After college and for a long time thereafter in Vermont, Sanders dabbled as a freelance writer, where he wrote a series of speculative essays on a range of issues, including the psychological causes of cancer, the destructive effect of public education, and rape fantasies. They are, to put it nicely, a little much. But they are also indispensably Bernie, and you can see kernels of the politician he’d become in the overwrought passages he scribbled back then. He was obsessed then, as now, with fomenting a peaceful political revolution, of defeating not just an opposition party but of fundamentally rebuilding the social and economic structures of society. This passage, from a 1969 essay, sticks with me:

The Revolution is coming and it is a very beautiful revolution. It is beautiful because, in its deepest sense, it is quiet, gentle, and all pervasive. It KNOWS. What is most important in this revolution will require no guns, no commandants, no screaming “leaders,” and no vicious publications accusing everyone else of being counter-revolutionary. The revolution comes when two strangers smile at each other, when a father refuses to send his child to school because schools destroy children, when a commune is started and people begin to trust each other, when a young man refuses to go to war, and when a girl pushes aside all that her mother has ‘taught’ her and accepts her boyfriend’s love.

The revolution comes when young people throughout the world take control of their own lives and when people everywhere begin to look each other in the eyes and say hello, without fear. This is the revolution, this is the strength, and with this behind us no politician or general will ever stop us. We shall win!

One consequence of being one of the oldest people ever to seek a major party presidential nomination is that few candidates have left behind as rich a paper trail as Sanders. So take a moment to catch up on the Bernie Sanders back catalog. Read his manifesto on sexual freedom. Watch his TV show. (Yes, he had a TV show.) Study up on one of his political icons. But there’s no rush. If there’s one lesson we learned in 2016, it’s that he won’t be going away anytime soon.