A Facebook ad from the Trump 2020 campaign.Facebook Ad Library

The most famous ad of the 2012 presidential race featured an Indiana paper mill worker who described building a wooden stage upon which, a few days later, executives from Mitt Romney’s firm would announce they were shutting down the plant. The ad was created by a Priorities USA Action, a super-PAC backing Barack Obama whose ads succeeded not only by portraying Romney as a heartless capitalist, but also by targeting voters in key swing states before Romney had his own operation up and running. Beginning six months before the election, these ads gave many voters their first sense of who Romney was, an image he was unable to shake.

Eight years later, Democrats’ goal is once again to define their opponent early and set the terms of the election against President Donald Trump. Except this time, the main battleground is not TV but digital advertising. And some Democratic digital consultants fear that Trump is already beating them to it.

“My worry is that my colleagues in the Democratic Party and funders are going to invest heavily in things that will be operational once we have a nominee, and the campaign is being defined right now, today,” says Ben Coffey Clark, a founding partner at the Democratic digital advertising firm Bully Pulpit Interactive. “Lots of people aren’t watching TV news, aren’t reading enough news, and so what they’re hearing from their friends and what they’re seeing from advertising from the Trump campaign is going to define the election for them if we’re not careful.”

Democrats have watched with alarm as the Trump campaign puts millions of dollars into digital advertising campaigns. In the past year, the campaign has spent more than $12 million on Facebook ads alone, compared to $9.4 million for the 16 top-spending Democratic candidates combined. Many of those ads are directed at building the campaign’s direct voter contacts—asking users to sign birthday cards for the president or fill out a survey in order to get their email addresses and phone numbers. Other ads are targeted at firing up the campaign’s base with red meat about border security, although a growing number are aimed at swing voters. As of last month, nearly a third of the campaign’s Facebook spending was going to five 2020 battleground states: Florida, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Texas, and Ohio.

While the candidates battle it out in the primary, “the Democratic Party as a whole needs to tell a bigger picture about why the Democratic Party will make regular people’s lives better, and how Trump has failed them, and what the choice coming up means in their lives,” says Clark, adding, “A huge chunk of that is going to have to be on Facebook.”

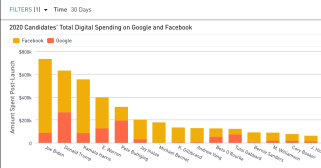

The Democratic primary campaigns are beginning to ramp up their digital spending. In the last month, for the first time, they combined to spend more than Trump, with Joe Biden, who announced his candidacy on April 25, leading all campaigns:

But the top-line numbers don’t tell the full story. Democrats’ spending is aimed largely at compiling the emails and phone numbers of potential donors and volunteers in states with early primaries and caucuses, such as Iowa and South Carolina, and in their home states and Democratic strongholds. That can help candidates gain an edge for the Democratic nomination, but it won’t do much to defeat Trump. Democrats’ ads, when they aren’t about listserv building, are often about specific issues like Medicare for All or the Mueller report—messages aimed at winning over primary voters who are already not going to support Trump.

Many of Trump’s ads aim to craft a general-election narrative about his presidency. A Facebook ad that ran this week claims, “As a result of President Trump’s AMERICA FIRST agenda, jobs are returning to the USA, the Steel Industry is BOOMING, our great Patriot Farmers are benefiting, AND our country is respected on the World Stage again.”

Historically, the party out of power has relied on outside groups to attack an incumbent president while the party is engaged in a primary, says Tara McGowan, the founder of Acronym, a nonprofit dedicated to helping Democrats build up their digital operations. McGowan has studied data released by Facebook and Google and concluded that that Trump is likely reaching a significant number of persuadable voters in key battleground states, in addition to his base. “The reason for alarm bells is that a lot of voters are going to be hearing this story that the president has kept his promises, that he’s under attack from the media, that he has really made gains on issues that he claimed he would champion in his 2016 election,” she says. “And Democrats are not telling a counter-narrative to those same voters yet, because they’re waiting for the leader to emerge.”

McGowan points to ads the Trump campaign has begun to run recently that are clearly general election messages. Some target Florida voters over the administration’s aggressive policy toward Venezuela; others tell voters in swing states about Trump’s accomplishments on criminal justice, or stress to a broad audience that the president is delivering on the promises he made in the last election. “I think the question we don’t know the answer to is: Is it harder to get a story across to voters like Priorities USA was able to do in 2012 when the opponent has been telling a different story year round?” she says.

After its success in 2012, Priorities USA grew into the premier super-PAC dedicated to helping Democrats win the White House. The group backed Hillary Clinton in 2016 and helped Democrats in the 2018 midterms. Now Priorities USA has signaled that it wants to take on Trump, and that it feels the time pressure.“The days of us just raising $200 million and then dumping a bunch of money on television in September or October are over,” Priorities USA chairman Guy Cecil told reporters last Friday.

Priorities USA’s focus right now is on mobilizing Democratic voters in key swing states to combat a drop-off in enthusiasm from the midterms. It’s spending $4 million on digital ads and staffing for local 2019 elections in Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania, a move the group argues will lead to more engaged voters in 2020. But it’s also trying to combat Trump’s digital operation, particularly when he pushes general election messages. Last month, the group used digital ads in Wisconsin to try to undercut Trump’s visit there, part of a digital ad campaign expected to total $100 million through early 2020.

“A big part of our mission, and the reason why we’re starting as early as we are, is to make sure he doesn’t get a head start on this,” Cecil said.

But even Priorities USA’s early investments are falling behind those of the Trump campaign. The group may need more money to combat a campaign that, combined with Republican National Committee, was sitting on $82 million in cash last month and has set the goal of raising $1 billion for Trump’s reelection.

Democrats have taken note of the importance of digital ads since 2016, when the Trump campaign’s digital strategist, Brad Parscale—since elevated to 2020 campaign manager—attributed Trump’s win to his online operation, particularly on Facebook. Democratic digital experts say that narrative is likely overblown but that it was nonetheless a wake-up call that their party had lost its digital edge.

It may be too late for a repeat of 2012. “I’m confident, just based on the level of investment Democratic primary campaigns are spending online, that whoever wins will run a smart cross-channel campaign to reach voters,” says McGowan. “The challenge that we really have right now is, how much time can we lose?”