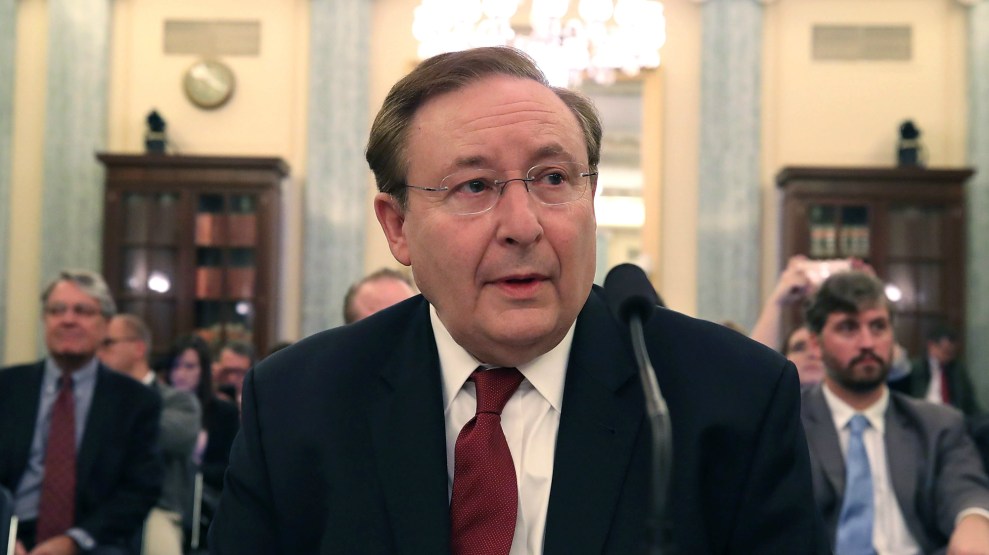

Barry Lee Myers participates in his Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee confirmation hearing to become administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, on Capitol Hill, on November 29, 2017.Mark Wilson/Getty

When she was just beginning her career at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, a current scientist, who asked not to be named, was on a three-week expedition. These are common for NOAA, a time for scientists and crew members to conduct research that informs global weather, climate, and ocean forecasting. Sending off teams of NOAA employees to far-flung areas produces crucial insights about our planet, but it may also have unintended consequences.

During this expedition, which took place in 2003, a crew member repeatedly pushed himself onto this scientist to “sandwich” her between the wall and himself. “He’s breathing down my neck,” she recalls. “He’s talking to me about…dating escapades and sexual relations he would have with young women, and he wanted to know if I did that kind of thing.” She kept trying to change the subject by asking questions like, “Can you tell me the angle you see on the instrument in the water so I can record it?” But he was not deterred.

Then another NOAA crew member on the same mission also started physically and sexually intimidating her. She told no one about these incidents, but when she finally disembarked, she received a letter from the executive officer on the boat telling her that the sexual harassment was reported, and the two individuals involved had been informed. “Someone else on the boat saw this happening,” she said. “My head was swirling when I got [the letter] and I didn’t know what to do with it.”

One of the harassers apologized and the behavior stopped, but the other was hostile toward her for years. A coworker told her that after the harassment was reported, the man who remained unapologetic and hostile had said once they arrived at the international port, “She better be careful because I can make her disappear.”

She did not leave NOAA and advanced in her career there. Then, in October 2017, when she and other scientists heard that former AccuWeather CEO Barry Myers might become NOAA’s new leader, many were concerned because of his potential conflicts of interest, which included his deep involvement in building the private weather company, his years spent lobbying to privatize NOAA’s public weather information, and the fact that he’s not even a scientist. (He stepped down as CEO of AccuWeather in January and divested himself of any ownership of AccuWeather, but his brother is leading the company.) Myers’ nomination languished for more than a year, but then at the beginning of April 2019, the Senate seemed to be in a rush to confirm him. The Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation moved his nomination forward for a floor vote, but that still hasn’t taken place.

Later in April, The Washington Post obtained a US Department of Labor report that found “widespread sexual harassment” at AccuWeather under Myers’ leadership, which further worried current and former NOAA employees, as well as other scientists. They remembered that in 2016, Congress passed the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Sexual Harassment and Assault Prevention Act, after several of the agency’s employees had come forward complaining about the situation there. They were aware that Myers was the head of AccuWeather when an investigation conducted by the Department of Labor’s Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs found that “AccuWeather was aware of the sexual harassment but took no action to correct the unlawful activity.”

“AccuWeather clearly denied the allegations and claims raised after the audit, and we continue to deny the allegations and claims,” the company wrote Mother Jones in a statement via email. “[T]o ensure AccuWeather is the most welcoming, inclusive, empowering and the very best workplace it can be for all our team members,” the company said it has put in place trainings, surveys, a method to handle anonymous complaints through an outside third party, and updated their written policies. AccuWeather also agreed to pay $290,000 as part of a settlement.

Myers wrote in a letter to the editor published in the Post, “Many organizations have employee issues in the work environment. The leadership test is doing the right thing when issues arise.” He did not respond to a request for comment by the time of publication.

For many employees, the combination of the history of sexual harassment at NOAA, the lack of support for Myers, and then the problems at AccuWeather when he was in charge, made his nomination even more concerning. Jane Lubchenco, who served as NOAA administrator from 2009 to 2013 and publicly opposed Myers’ nomination, said NOAA “has been working diligently to improve the climate for a safe, healthy workspace and would be particularly vulnerable to having someone whose track record is the opposite of overseeing a healthy productive work environment.”

She said that even without a confirmed administrator, NOAA can continue to do what it’s supposed to do, but “it’s not directly connected to the rest of the administration.” Lubchenco added, “That said, it is far better to have an acting administrator that is competent than a confirmed administrator who is rife with conflicts of interest and not a competent leader.”

Jane Willenbring, a professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, and Amy Freitag, a contract social scientist for NOAA, also expressed their opposition to Myers. In an op-ed entitled, “Bury Myers’ NOAA Nomination,” published on the Union of Concerned Scientists blog, they wrote:

Myers claimed to be unaware of rampant and pervasive sexual harassment in a company of only about 500 office employees, How are we to have any confidence that he will have the capacity to ensure that an agency with 11,000 employees and contractors, many of whom are at sea and in remote locations, is aggressively enforcing an anti-harassment policy? As we both know all too well, serial harassers thrive in isolate environments where their victims have little recourse.

Willenbring had faced sexual harassment from the professor leading her first field expedition to Antarctica, when she was a masters student in 1999. “It can be incredibly hard to navigate sexual harassment even when you can go home to your spouse or loved one,” Willenbring told Mother Jones. “When you’re out in the middle of nowhere and there’s no way of getting away from the person, it’s particularly important that people are supported.”

Concerned about retaliation, Willenbring waited nearly two decades to file a complaint against her harasser and former thesis advisor. Once she gained tenure at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, she finally felt safe to report the professor, who was ultimately fired for violating Boston University’s sexual misconduct Title IX policy.

The NOAA scientist who spoke with Mother Jones noted that one of the young women she supervised had worked with the same crew member who had harassed her years before. When the other scientists were busy, the young woman was alone with the crew member. The scientist described her entering the lab in tears saying, “It’s exactly like what you said. He was leaning on me and breathing on me and telling me how beautiful and young I am.” The crew member never faced repercussions, as far as the NOAA scientist knows, and he retired last year.

“There’s no such thing as tenure at a government agency,” Willenbring said, “so it’s even more important that there’s a culture that protects people who are willing and brave enough to come forward. Otherwise, nothing will ever change.”

As of now, there is no Senate vote scheduled for Myers’ confirmation.