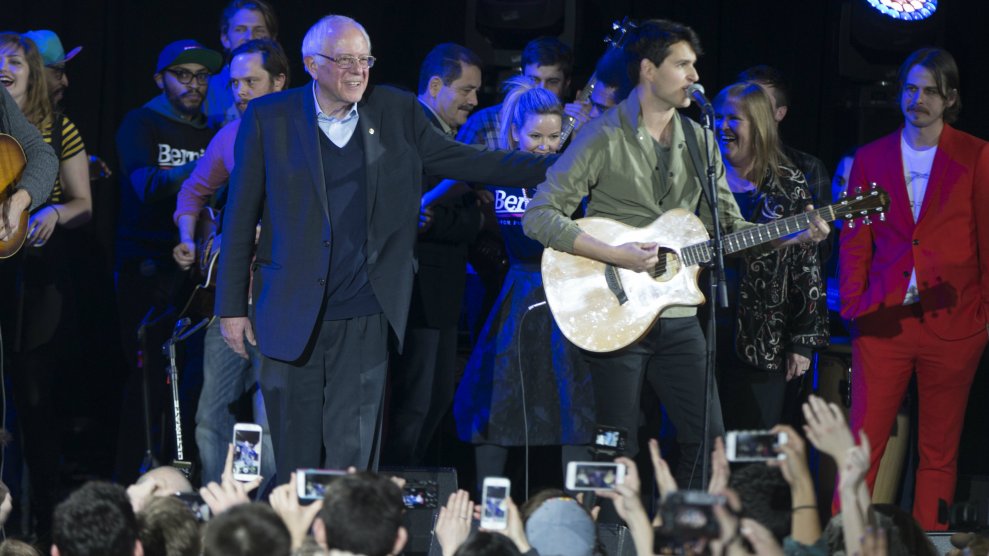

John Locher/AP

BerniePanic has set in. As the Iowa caucuses approach, Democratic establishmentarians and we-gotta-beat Trump pundits have begun to fret about the Sanders surge. They fear the prospect of the Vermont (small-d) democratic socialist triumphing in the Hawkeye State, winning in New Hampshire, and then becoming an unstoppable force in the remaining primaries.

On MSNBC’s Morning Joe, Steven Rattner—the financier-commentator and Mike Bloomberg moneyman who channels the hopes and worries of the Democratic corporate crowd—has been proclaiming that Sanders’ wide-ranging agenda scares the hell out of his Wall Street pals and warns it will be too much for most voters in November. Thus, he argues, the Democrats are doomed to lose to Donald Trump, should they anoint Sanders as their nominee. Commentators Jonathan Chait (of the center-left) and David Frum (of the center-right) have each weighed in with articles that somberly point out Sanders’ vulnerabilities in a general election race against Trump. Chait contends Sanders would be “an extremely, perhaps uniquely, risky nominee. His vulnerabilities are enormous and untested. No party nomination, with the possible exception of Barry Goldwater in 1964, has put forth a presidential nominee with the level of downside risk exposure as a Sanders-led ticket would bring. To nominate Sanders would be insane.” Frum calls Sanders a “fragile candidate.” And he notes, “He has never fought a race in which he had to face serious personal scrutiny. None of his Democratic rivals is subjecting him to such scrutiny in 2020…The Trump campaign will not steer clear. It will hit him with everything it’s got.”

They’re all correct. That is, correct to be concerned. While it’s a foolhardy exercise to state unequivocally you know what will play or not play with the electorate these days, their points—which might enrage Sanders supporters—are not without foundation. Sanders is pushing progressive programs that often poll well and that are mainstays of other Western democracies, but the overall price tag and the sweeping nature of his proposals could well alienate voters who aren’t in it for a revolution. (But, as his camp argues, this could attract other, perhaps new, voters.)

It is without question that Sanders has never been hit with the kind of massive, negative assault that awaits. If he is the Democrats’ flag-bearer, he will be pounded by at least $500 million in attack ads blasting him for being a tax-and-spend commie who wants to destroy the free-enterprise system that’s been the bedrock of American society for generations. Certainly, Sanders can retort, Everyone knows I’m a democratic socialist. So what’s the big deal? But this blitzkrieg could well be the dirtiest political crusade of all time. (Remember, the slurs won’t have to be true and accurate.) A blistering assault will greet whoever the Democrats pick. But political observers are right to point out that Sanders has not been tested in this fashion during his long career, and no major party nominee has ever had to defend himself as a self-proclaimed socialist and revolutionary. How will Sanders fare when this fusillade comes? It is a legitimate concern.

No one can pretend to know the unknowable, and electability may be the most unknowable thing in politics. Yet one way to look at Sanders’ chances—and whether Democrats who desire, above all else, a de-Trumpification of the White House ought to fear his nomination—is to ask this question: Is Sanders George McGovern, or is he Donald Trump? Each was an affront to the establishment of his party. One was trounced; one sidestepped his way into the White House.

In 1972, McGovern, the Democratic senator from South Dakota, ran as an outright liberal. He was a prairie populist, a war hero, and quite a decent man. Four years earlier, the party had torn itself apart in a bitter race. After President Lyndon Johnson, beleaguered by the opposition to the Vietnam War, was almost beaten by anti-war candidate Sen. Eugene McCarthy in the New Hampshire primary, Sen. Robert Kennedy, a war skeptic, jumped into the race. Soon Johnson dropped his reelection bid, and Vice President Hubert Humphrey—who had stuck with Johnson on the war—entered the contest. Kennedy, who came to overshadow McCarthy as the main foe to Humphrey, was assassinated the night he won the California primary. Humphrey, the Democratic establishment’s man, went on to bag the nomination at a bloody and contentious convention in Chicago. With his party battered, Humphrey lost narrowly to Richard Nixon.

The next time around, McGovern, with his unapologetic liberal platform, rallied the anti-establishment energy and resentment within his party. He cruised past the Democratic poohbahs’ favorites: Sen. Edmund Muskie of Maine and Sen. Scoop Jackson of Washington. (Humphrey gave it another shot and faltered.) McGovern was perhaps helped by the Nixon dirty tricksters who targeted Muskie and the other Dems. A failed assassination attempt on Alabama Gov. George Wallace ended his racist and populist campaign and sidelined this threat to the party. McGovern, the liberal crusader, ended up with the party’s nod.

Nixon and his team were delighted. (Remember the scene in All the President’s Men, when Deep Throat tells Bob Woodward, “They wanted to run against McGovern. Look who they’re running against.”) They pilloried McGovern. He was championing big ideas, including a guaranteed minimum income for poor Americans and amnesty for those young Americans who had dodged the draft to escape service in Vietnam. As the New Yorker noted, the sleazy, whatever-it-takes Nixon gang was “successful in tarring McGovern as a wild-eyed, untrustworthy maniac committed to ‘amnesty, abortion, and acid.'” It worked. An earnest patriot who had gallantly flown combat missions in World War II was turned into an un-American freak.

McGovern, the insurgent candidate who had vanquished the establishment’s preferred choices, led his party to a historic defeat, carrying only one state (Massachusetts) and the District of Columbia. In the decades since then, no lefty insurgent has beaten a more establishment-friendly contender in a Democratic presidential contest. (Barack Obama did vanquish Hillary Clinton in 2008, but he did not truly run as an outsider. He was the keynote speaker at the party’s 2004 convention, after all.) Was the lesson of 1972 for the Democratic Party, don’t pull a McGovern?

The Republicans had their own poli-sci experiment in 2016. Trump ran as a bomb-thrower who wanted to blow apart his party—and just about everything else. The establishment favorites, former Gov. Jeb Bush and Sen. Marco Rubio, didn’t stand a chance. And Trump fended off a threat from Sen. Ted Cruz, who was running as a quasi-outsider: a pure conservative ideologue fed up with the supposed compromises of his own party. Trump captured the energy of the widespread resentment that ran through the Republican base, which seemed to be pissed off at everything: Washington, the GOP, corporations, Obama, Hollywood, the media, immigrants, and the poor. He was an extremist—a bully, a bigot, a belligerent liar, and scoundrel. He had come to prominence politically as the number-one advocate of the racist birther conspiracy theory. His ideology was an incoherent mixture, mostly concocted of conservative brew and Fox News misinformation. But ideology was not his brand. His platform, if you could call it that, was not a reflection of, say, National Review policy articles; it was a collection of hot buttons. And the Wall, the Wall, the Wall.

He can’t win. That’s what his dozen-plus foes in the Republican primary said. It’s what the GOP establishment and its media allies said. But his extremism—in style and insult, if not in ideology—galvanized Republican voters who were fed up with the party’s same-old/same-old. They wanted big changes, meaning they wanted things smashed. They didn’t care about the old rules and the conventional niceties. And Trump vowed to do the smashing. He also made vague promises about bringing about economic miracles, the way an experienced pitchman (or con man) sells his wares. All that jazzed up GOP voters—who had become radicalized via the tea party movement and the conservative media. Appealing to the red-meat cravings of Republican voters, Trump smacked down a GOP field that Republicans had boasted was one of the best and most-talented crops of potential POTUSes ever.

Having successfully mounted a hostile take-over of the GOP and snagged the nomination, Trump stuck with his schtick: He would rattle and remake the established order and, by sheer force of his oversized will, spark an economic renaissance and Make America Great Again. The lines of attack to use against Trump were obvious and many. Republicans had tremendous reason to clutch their pearls. Trump was roundly and accurately assailed for his ignorance, inexperience, bluster, misogyny, bigotry, and cheating ways. But…so what? The grab-’em-by-the-pussy tape confirmed what was already known—and that did not stop him. His act was not a crowd-pleaser for most Americans. But his anger, his phony populism, and his reality-TV brand of celebrity insurgency won him tens of millions of votes. This included Americans who bought his big, flim-flammy promises and who yearned to see the profound changes he claimed he could bring about. Drain the swamp! Build infrastructure! The best and most beautiful health care (as long as it wasn’t Obamacare). Winning and more winning.

Trump lost the popular vote. But (with Kremlin assistance) he attracted enough voters with his radical campaign to thread a needle in the Electoral College. The guy who many predicted would drive the GOP off a cliff managed to do what John McCain and Mitt Romney could not: He won. The most wild outsider in modern American politics—the most unelectable candidate—had seized control of a major political party and bullied his way into the White House. What’s the lesson there?

Unelectable—that was said of both Trump and McGovern. In one instance, this was right. In the other, not so. Is the question of ideology the main difference between these two cases? McGovern was a warm and intelligent man. He was deemed a long-shot because of his ideas. Trump is a sociopath. He was deemed unelectable because of his checkered past and fundamental flaws as a human being. McGovern was demonized by the GOP attack machine for his policies. Trump could not be demonized by the Democrats because he was already known as a demon.

So what’s the model for Sanders: McGovern or Trump? If he becomes the Democrat Party’s nominee, will he be successfully vilified, through a half-billion-dollar vicious ad campaign, as a left-wing extremist outside of mainstream Americanism? Or will his run as a populist maverick inspire voters who are outraged by both Trump and politics as usual, and who crave wide-ranging changes in American society? Sanders, of course, has none of Trump’s racism or scam artistry, but could he harness the anger of disaffected voters in a more positive manner?

Both scenarios are possible. Should the first transpire—Sanders is crushed by an unrelenting campaign of defamations and smears—it would be far less startling than the second. After all, no socialist champ has ever won the presidency. And if that second course comes to pass—Sanders seizes the imaginations of tens of millions of voters, and his call for a political revolution wins the day—it would seem astonishing. Just as Trump’s win was astounding. So the Sanders question, boiled down, is a contest between conventionalism and imagination. And where one lands might depend on whether or not you believe in surprises.