Mayor Michael Bloomberg in 2008, days before he announced plans to seek a third term. Craig Ruttle/AP

Shortly after noon on October 2, 2008, Michael Bloomberg—nearing the end of his second, and what should have been final, term as mayor of New York City—addressed a packed room in City Hall with clear intentions. “In recent weeks and months, as you know, I’ve listened to many different New Yorkers, with lots of different opinions on the issue of term limits,” he said. “But as our economic situation has become increasingly unstable, the question for me has become far less about the theoretical and much more about the practical.” The 2008 financial crisis had reached its apex; weeks earlier, investment bank Lehman Brothers had collapsed and filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The day after Bloomberg’s presser, President George W. Bush would sign a bill to give the banks responsible for the whole mess a $700 billion bailout. New York City, like the rest of the country, was in rough economic shape and Bloomberg—whose $20 billion estimated worth at the time was unscathed—believed he should be given the chance to continue his job and help pull the city out of it.

But Bloomberg had a problem: New York City had a strict two-term limit for elected officials—a fiercely popular measure that voters had twice overwhelmingly voted in favor of, in 1993 and 1996. Public polling at the time showed little support for abolishing or extending term limits. So Bloomberg and his staff concocted a plan that sidestepped the traditional democratic process, instead using the City Council to introduce an unusual bill that allowed people currently holding office the ability to serve a third term. It was a risky political move—a backdoor effort that undermines the will of voters—but Bloomberg had spent months behind the scenes courting support from council members, charitable organizations, and even the editorial boards of the city’s biggest newspapers to back his plan. It was an effort that exemplified how Bloomberg, as mayor, used his immense wealth to get what he wanted. “He ‘does not care what it costs’ to win a third term,” a former advisor told the New York Times at the time.

As Bloomberg learned during his time as mayor, there was hardly a problem he couldn’t make go away with enough money. Nearly $3 billion in donations, most of it to local arts organizations, charities, and other civic groups during his 12 years in office, bought him a kind of loyalty and support akin to a mafia boss. When unions would tangle with Bloomberg over contracts and policies, for example, reliable allies from local churches and other civic groups would remain silent. “For years we would try and do actions to counter some of Bloomberg’s harsh policies and just couldn’t get some of these groups to join us,” says Patrick Markee, who served as a senior policy analyst for the Coalition for the Homeless during Bloomberg’s tenure as mayor. “And many times they would tell me off the record or privately, ‘We can’t do anything, he’s a big donor and we’d get in trouble.’”

“He had such incredible wealth to spread around, that nobody dared cross him by speaking the obvious truth,” adds Mary Brosnahan, former president and CEO of the Coalition for the Homeless, who sometimes sparred with Bloomberg over policy issues. In the days and weeks after Bloomberg’s announcement at City Hall on October 2, 2008, powerful civic leaders who had previously disavowed the idea of abolishing term limits came out of the woodwork to support the mayor’s efforts. It was all part of an intense pressure campaign that Bloomberg and his deputy mayors mounted on his vast network of arts, neighborhood, and community organizations that heavily relied on his massive charitable contributions. At least one of those organizations, as revealed years later on their tax returns, received millions of dollars in donations from Bloomberg during this time.

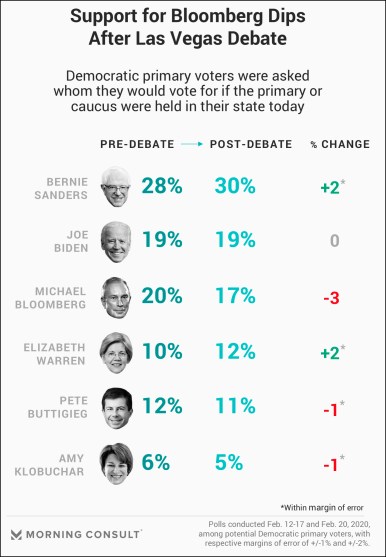

Now, as Bloomberg’s quest for the Democratic presidential nomination shifts into high gear, the power of his $62.8 billion fortune is being tested like never before. Bloomberg has spent nearly half a billion dollars of his own money so far—a fraction of a drop in the bucket for him—since he launched his campaign in November, flooding the airwaves with ads, spamming the internet with memes, and building an army of staffers so big that other campaigns are having trouble staffing up. “What he’s doing is duplicating what he did in the city, but putting it on a national scale,” says Douglas Muzzio, a political science professor and longtime political analyst at Baruch College. “If you have that much wealth, you can build an amazing wagon.”

Both Brosnahan and Muzzio have seen up close how that wagon is built. Just weeks after Bloomberg announced his intentions to stay in office, the City Council voted on the bill that would pave the way for his third term. And in that time, Bloomberg’s deputy mayors had mounted a massive pressure campaign to drum up support, as the New York Times reported at the time:

An official at a social service group that receives tens of thousands of dollars from Mr. Bloomberg and has a contract with the city was startled to receive a call in the past few days from Linda I. Gibbs, the deputy mayor for health and human services. Ms. Gibbs asked whether the organization’s leaders would be willing to call wavering council members to argue for Mr. Bloomberg’s term limits legislation.

“It’s pretty hard to say no,” the official said, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear of upsetting the mayor. “They can take away a lot of resources.”

It worked. During the public hearings in the days leading up to the vote, dozens of people testified in front of the council. Most who testified did so in support of the bill to extend term limits, explaining that they previously voted in favor of term limits but thought that the law should be amended to keep Mayor Bloomberg in place, an analysis of public testimony records shows. “Under normal circumstances would I be in favor of term extensions? No, I would not,” wrote Geoffrey Canada, CEO of Harlem Children’s Zone, an organization that provides services for children and families that had received more than half a million dollars in donations from Bloomberg in the six years he’d been in office at that point. “But under these circumstances I think we need a steady, seasoned veteran such as Mayor Bloomberg.”

And a majority of those who testified were people publicly affiliated with, or secretly sent by, one of several nonprofit organizations that received significant contributions from Bloomberg, including the Harlem Children’s Zone, the Public Art Fund, and the Doe Fund—a nonprofit homeless services organization that was one of Bloomberg’s biggest champions at the time. Markee vividly remembers the “van loads” of Doe Fund clients—homeless residents who were getting minimum-wage work and receiving shelter from the organization—who were transported to City Hall to testify in support of the term limits bill. “They essentially gave them a prepared script and told them to go in and just line up and testify one after one,” he remembers. “They were essentially just told, ‘As part of your job today, we’re taking you down to City Hall and you’ve gotta testify in favor of giving Bloomberg a third term.'”

“It saddened me to see them used like that, as such tokens,” Brosnahan says. Muzzio also remembers the people in red shirts who filled the council chamber. “I asked somebody to my right and he said, ‘They’re all from the Doe Fund,’” he recalls. “It sort of clicked at that moment that the charitable contributions from Bloomberg were political contributions in a sense. He knew they would have a political impact.” Two years later, it was revealed that the Doe Fund had received tens of millions of dollars at that time in donations from the mayor. In response to inquiries about the organization’s role in advocating against term limits on Bloomberg’s behalf, a spokesperson for the Doe Fund tells Mother Jones that “George McDonald, Founder and President of the Doe Fund, has always opposed term limits. He has been vocal about his opposition every time the issue arose.” (Bloomberg’s presidential campaign did not respond to a request for comment.)

In a 29–22 vote, the council paved the way for Bloomberg’s third term. Not everyone was excited about the vote. People in the balcony of the chamber erupted in chants of “The city’s for sale!” and “Shame on you!” according to the Times. Later, upon hearing that the bill passed, Bloomberg told the Times, “I had a smile on my face. Also a little bit of a tinge of, ‘Oh, my goodness! I hope I know what I’m doing here. We’re going to have some very tough times.’”

So far, Bloomberg’s campaign has become something of an unprecedented political experiment. Not just in how much he’s invested in his own campaign, but what the many billions he’s spent on political contributions and philanthropic efforts might buy him. Bloomberg Philanthropies, the charitable arm of his business empire, has given away billions for liberal and social justice causes—environmental issues, humanitarian efforts in the US and abroad, education, government innovation, and the arts. And a lot of that money has supported cities across the country, which so far has helped him earn the endorsement of more than 100 mayors—some of whom have joined the campaign. His political action committee, Independence USA, spent more than $38 million to boost Democratic candidates during the 2018 midterm elections, which helped flip party control of the House of Representatives to Democrats. At Tuesday’s Democratic debate in South Carolina, Bloomberg mentioned this effort but appeared to say he “bought” Democrats before catching himself at the last moment and saying “I got them.” One of Bloomberg’s most visible philanthropic efforts has been on gun control, where he founded the influential Everytown for Gun Safety and its subsidiary organization Moms Demand Action. And upon entering the 2020 race, Bloomberg did so with access to the vast trove of email addresses that Moms Demand had acquired in its eight years of gun control advocacy work.

“My worst fear is that the country is going to have to relearn the same lessons that we learned here, as they did with Trump,” Brosnahan says. “We all knew that he was a blowhard and a scam artist. Now do we have to watch the nation learn that this guy was not a successful mayor?”