“Sorry, I’ve got a mild buzz going. I’ve been going since like 8:30,” an off-duty federal law enforcement officer told me, nodding at a tumbler in his hand. It was almost noon. He wouldn’t tell me his name, citing the Hatch Act and explaining that “employees of the executive branch of government can’t support candidates for government.”

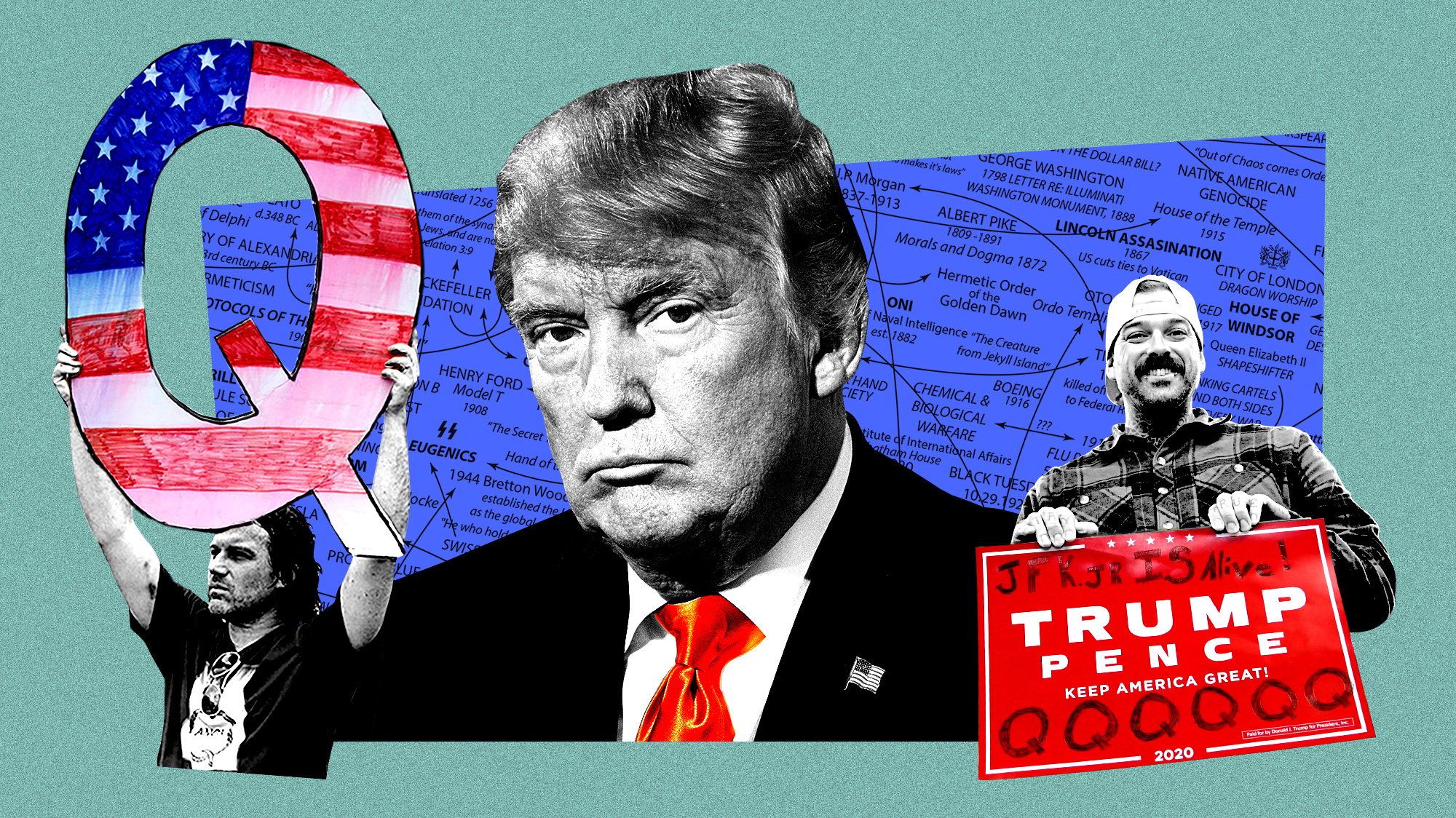

We were standing in line in Minneapolis for a Trump campaign rally scheduled for that October evening, talking about QAnon. He and a couple of other friends were tailgating like it was an NFL game. Except instead of “Skol, Viking” their signs read “Declass brings down the house,” referencing the core QAnon belief that declassifying certain government documents would trigger mass arrests of liberal elites who have, for years, run a secret pedophile ring. This myth, along with the rest of the sprawling QAnon conspiracy, started in 4chan message boards in 2017 before moving to the more notoriously toxic but now defunct 8chan, after which, with the help of YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter, it went massively viral.

I asked what he thought was the appeal of the conspiracy theory. “Jeez,” he said after a pause. “I think there are aspects of all society that’s involved in crazy shit that nobody knows about.” After a few minutes of further probing, he eased up a bit, leaned over, and lowered his voice: “People say, ‘Oh, there’s a pedophile ring.’ That stuff is bullshit. I don’t know if that’s real. What I do know is real is all the politicians—they’re all against Trump.”

The unnamed federal agent was one of a few proud Q supporters hanging out ahead of the president’s appearance, part of a larger group that for much of 2019 had been flooding Trump rallies across the country. But at least on that day outside the Target Center, their numbers appeared to be waning.

Listen to reporter Ali Breland explain the ways the online QAnon conspiracy’s adherents have evolved, and how they surface at offline Trump rallies, on the latest Mother Jones Podcast:

Trump rallies are, at this point, a spectacle that the media had long ago gotten used to. But during a July 2018 Tampa rally, something different popped up that confused most journalists: Scores of people were wearing shirts emblazoned with the letter “Q.” They bore signs that said things like WWG1WGA—short for “Where We Go One, We Go All” and “The Storm Is Upon Us”—two stock phrases beloved by the conspiracy’s adherents.

After the Tampa rally, national media outlets rushed out stories explaining that Q referred to “QAnon,” an anonymous internet poster who claimed to have inside information revealing that, despite outward appearances and all evidence, Donald Trump is a brilliant tactician working to take down a pedophile ring run by a cabal of Democratic and Hollywood elites, but whose efforts are being undermined by the “deep state.” QAnon adherents, like more mainstream Trump fans, use that term to describe a vague but supposedly entrenched network of unelected bureaucrats inside the federal government who are opposed to the president, particularly in the intelligence community.

After Tampa, adherents kept showing up. There was a notable blossoming at a February rally in El Paso, Texas, followed by an eruption in March in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where they “turned out in force.” Another big appearance occurred at a May 2019 rally in Panama City, Florida. In Cincinnati that August, the crowd erupted when one of Trump’s opening speakers warmed up the room by using the “Where We Go One, We Go All” catchphrase.

Already stunned by the number of QAnon folks at this Panama City Beach Trump rally

— Christopher Mathias (@letsgomathias) May 8, 2019

After each of these rallies, dozens of Q-centric pictures taken at the events popped onto social media. Photos of seemingly run-of-the-mill families, decked out in shirts and hats with giant Qs and other symbols and popular QAnon phrases, went viral.

While their outfits suggested a certain devotion, did throngs of soccer moms and middle-management husbands actually believe that federal bureaucrats were working relentlessly to thwart Trump from taking down a massive yet invisible pedophile ring? Or were they just supportive of the broad contours—the anti-corruption, pro-conservative underpinnings of QAnon—without closely scrutinizing the details in between?

It was hard to find answers to these questions in Minneapolis because it was difficult to find QAnon supporters at all. Q’s once-unmissable presence at Trump rallies appeared to be receding. They were still there, but fewer and farther between.

This seemed markedly different from past rallies. “I can say definitively is that I was blown away by the ubiquity of Q people at these rallies,” Christopher Mathias, a senior HuffPost reporter who covers the far right, told me, saying that each of the five rallies he went to in 2019 had an overwhelming and obvious QAnon presence.

Of the few that did show in Minneapolis, when I spoke with them, many seemed to be deeply committed, quickly recommending their favorite QAnon YouTube channels and outlining their thoughts on obscure and especially outlandish bits of the sprawling theory. YouTube, along with Facebook and Twitter, was where almost all of them seemed to have gotten “redpilled”—or indoctrinated into the cult of Q.

Others, like the federal agent, were less sure that John F. Kennedy Jr. was still alive—another baseless and widespread Q notion—or that there was a massive pedophile ring.

The paucity of Q fervor doesn’t seem to be just a Minneapolis phenomenon. While it’s difficult to tell the presence of QAnon at rallies without being there, the amount of related content posted to social media at subsequent rallies suggests a decline. A Twitter user who attended an October Dallas rally told me that Q supporters were “visible if you knew what you were looking for” but that they’re “definitely a minority.”

The crowd in line for a Trump rally in Hershey, Pennsylvania, in December also seemed to have just a scattered presence of Q devotees. Except for two women wearing Q earrings, most of those I saw were less invested in the core beliefs of QAnon than in its overarching message of anti-corruption and harsh opposition to liberal elites.

One valuable source of information about QAnon supporters’ presence at rallies are the vendors who, like Grateful Dead parking lot entrepreneurs, make a living setting up shop outside Trump events across the country. “Mass arrests, pedophiles? Nah…that’s just gossip,” Jonas Williams, a 46-year-old merchandise vendor, told me. While Williams said he was a QAnon supporter, he wasn’t selling any Q gear. He shied away from the more bizarre details, saying he just appreciated the corruption fighting and anti-liberal sentiment pushed by the conspiracy.

Another traveling vendor in Hershey, David Dickson, confirmed my sense that there were even fewer people wearing QAnon gear than at past rallies or even in Minneapolis, which already seemed to have a lower turnout.

“It’s definitely decreased,” Dickson said. He suspected that Q support hasn’t disappeared, but that it’s just an unspoken part of MAGA culture, present but secondary to their support of the president. Adherents don’t feel the need to differentiate their support of the conspiracy or publicly represent it. When I approached visible supporters at the rallies, they often pointed me to another fan nearby who didn’t have any Q paraphernalia.

“It’s really died off in the last six months,” one Trump merch vendor in Hershey, who’d traveled from Pittsburgh, told me. He said he’d once been into Q but his interest had faded as the conspiracy got more ambling and bizarre.

Other vendors knew about QAnon but were uncomfortable talking about it. Several said they stopped selling Q merch after the campaign supposedly blocked people who were wearing it from coming to its rallies, which interviewees speculated help quell Q’s visual presence.

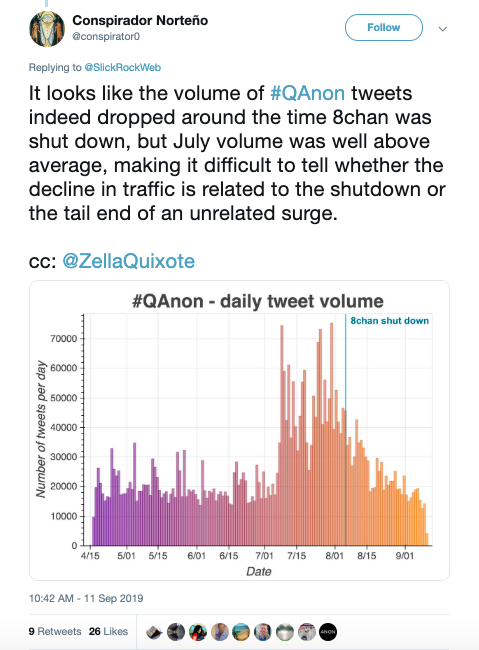

There’s evidence apart from rally attendance suggesting QAnon might have experienced a broader decline over the past year. Analysis of tweets shared by a researcher who goes by the pseudonymous handle @conspirator0 shows a steady drop in the amount of QAnon-related tweets since July. (Since this data was collected, Twitter has tightened researchers’ data access site, hindering the creation of any updated version.)

“QAnon feels like it’s in stasis right now,” said Travis View, a researcher who has tracked the QAnon conspiracy community and co-hosts the podcast QAnon Anonymous. “But even if the movement is waning, there are still plenty of true believers who will probably become more cemented and radicalized over time.”

A committed Q faithful is still causing problems and, as the New York Times has documented, finding ways to spread the conspiracy offline. Most recently, Montana police arrested a QAnon follower who’d enlisted believers into a kidnapping plot, seemingly motivated by paranoia of “evil Satan worshipers” and “pedophiles.” In May, Yahoo News reported that the FBI had determined QAnon and related conspiracies are a domestic terrorism threat. A QAnon obsessive murdered a mob boss in March; his lawyer later told a court that his client thought his victim was a member of the deep state. In June of 2018, a Q supporter was charged with terrorism after he drove an armored truck with several guns to the Hoover Dam, saying he was on a mission to call for the government to “release the OIG report,” a Justice Department watchdog investigation that QAnon believers anticipated would present lurid evidence about Trump opponents.

In September, before heading to the Trump events, I spent time with devout Q backers at a rally they held on the National Mall in Washington, DC. They assured me they believed in QAnon and many of its most bizarre claims about pedophilia cabals, and wanted to “redpill” as many others as they could into believing them too. True to form, I saw one attendee chase down a family of foreign tourists who spoke limited English, asking if they “had heard about QAnon.” After confusing and alarming them, he gave up and let them get back to their vacation.

While QAnon wasn’t nearly as omnipresent at recent Trump events in the way Mathias had seen at past rallies, there were some holdouts in Minneapolis.

“Yes, there is pedophile ring and human trafficking,” a middle-age Minnesotan named Steve who was attending the rally with his wife, Lisa, told me. He was less sure John F. Kennedy Jr. was still alive but still thought there was a solid possibility.

For some, Q has become less of a conspiracy than a way of signaling opposition to corruption, usually coming from Democrats and liberals. Like the federal agent, many Trump supporters, merch vendors, and others I spoke with would empathetically endorse Q at the start of conversations but back down when probed on its most paranoid conspiratorial details. In this way, QAnon persists but for many is no longer firmly attached to the original insane, detailed conspiracy.

It’s also possible that the decline of Q is regional, with support remaining in geographic pockets. The rally where Q made its national news debut was in Tampa, and another rally organized by QAnon, where supporters flocked, was in Panama City, Florida. A Washington Post poll last August found that 58 percent of Floridians knew enough about QAnon to have an opinion about it. According to a tally from Media Matters, there are six congressional candidates running in Florida who have backed QAnon in one form or another.

Still, many folks I spoke with at the Trump rallies felt like Q was done. The theory’s main posting hub, 8chan, got booted from its host server in August after three white supremacist shooters posted manifestos there before carrying out killing sprees, effectively taking the website down. Suddenly, the constellation of sites, YouTube channels, and social media users that had broadcasted and speculated on the meaning of cryptic new Q posts on 8chan—followers call them Q drops—lost a major source of the intrigue that was driving attention their way. Readers who had been following along since Q first posted in 4chan in 2017 no longer had a constant stream of fresh content to pore over.

The loss of 8chan came too late to fully quash the following that Q had built, but the lost momentum suggested that deplatforming has had an impact. “It’s kind of stopped now. The last post was in August,” said one middle-age woman on her way into the Minneapolis rally who, along with her husband, declined to give me her name.

By the time I made it to the Hershey rally in December, the poster claiming to be Q has posted again on 8Kun, which was launched in November by the people behind 8chan, but in Pennsylvania that day it didn’t seem to have made much of a difference. Q had already faded.

Even if it has receded, for many of the people still holding onto Q, it meant something very real for them. Q followers all seemed to believe that the conspiracy had helped them gain access to the truth and that they’d done so by thinking for themselves.

As that woman in Minneapolis proudly told me, “You don’t just listen to anybody. You research it yourself.” The media, to them, was lying to the public, but all of the information needed to stay properly informed was still out there if you know where to look for it. It didn’t seem like they were planning on giving up on that idea anytime soon.