Justin Sullivan/Getty

This was the week that Bernie Sanders ran smack into a great American myth. That myth is that the United States nobly won the Cold War, which was a black-and-white clash between the forces of good and free enterprise (us) and the forces of evil and communism (them). Sanders’ dabbling in Cold War politics, when he was mayor of Burlington, Vermont, became campaign fodder, as he solidly assumed the frontrunner position in the Democrats’ presidential nomination race. His trips to Cuba, Nicaragua, and the Soviet Union in the 1980s and his statements back then about conditions in those countries have come under scrutiny, with Sanders’ political foes and pundits pushing a blunt message: lefty Sanders was soft on commie dictators.

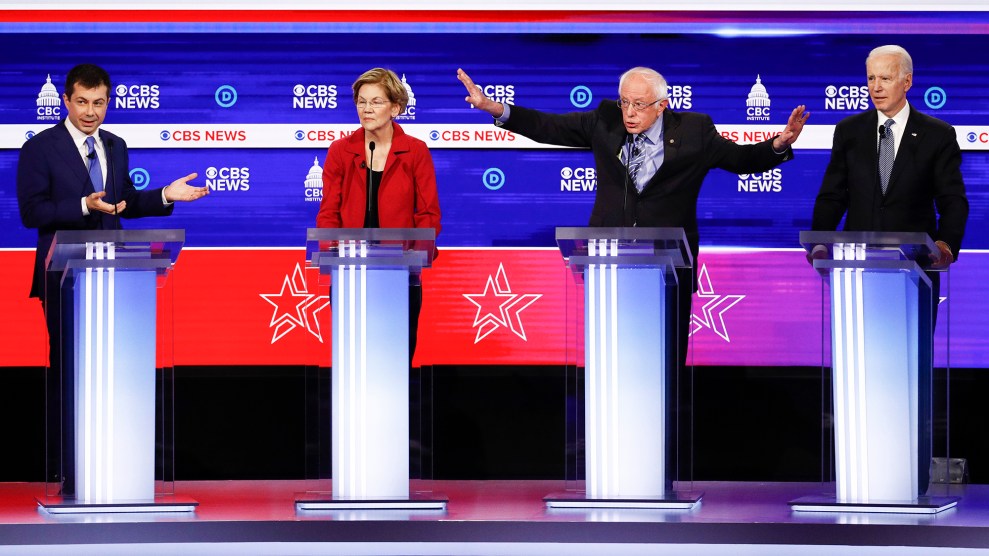

At the South Carolina Democratic debate on Tuesday night, Face the Nation host Margaret Brennan raised the matter with Sanders: “You also have a track record of expressing sympathy for socialist governments in Cuba and in Nicaragua. Can Americans trust that a democratic socialist president will not give authoritarians a free pass?” Sanders replied that he has “opposed authoritarianism all over the world.” He was booed by some in the audience, and excoriated by his rivals, with Pete Buttigieg accusing Sanders of hyping “the bright side of the Castro regime” and having “a nostalgia for the revolutionary politics of the 1960s.”

The chaotic back-and-forth at the debate and much of the discussion about Sanders’ past actions ignore the nuances and realities of the 1980s. This is not to say that Sanders’ views and remarks are beyond critique. But they are being slammed with little or no context.

The Ronald Reagan chapter of the Cold War was not a simple tale of right versus wrong. As Reaganite hawks embraced the militarism of the era, they increased geopolitical and nuclear tensions, and they cut deals with murderers, torturers, and drug runners. Since then, they’ve depicted this stretch as a time when a gallant Ronald Reagan bravely stared down the Evil Empire and won the day. The Berlin Wall crumbled. The Soviet Union collapsed. But it was far more complicated—and costly.

With the Reaganauts building up the nuclear arsenal and looking to deploy nuclear missiles into the heart of Europe, millions of Americans feared the East-West conflict could—purposefully or accidentally—lead to a nuclear war. It didn’t help that a Pentagon official early during Reagan’s first term downplayed the consequences of nuclear war and told a reporter, “If there are enough shovels to go around, everybody’s going to make it.” (Remember that the nuclear freeze movement mobilized people throughout the land and that Democrats battled Reagan on arms control policy.) The surrogate wars waged by Washington and Moscow in Latin America, Africa, and elsewhere contributed to the sense that a showdown could be on its way.

As the Cold Warriors pursued their crusade against the Soviet Union, they stuck to a version of the Domino Theory, which was once used to justify the United States’ misguided intervention in Vietnam. (That led to the deaths of more than 58,000 US soldiers and an estimated 3.3 million Vietnamese fighters and civilians.) So they bear-hugged anti-communist authoritarians across the globe: The anti-Semitic and fascist junta in Argentina, the apartheid regime of South Africa, the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines, the murderous tyrant Augusto Pinochet in Chile, and other thugs and killers. Jeane Kirkpatrick, Reagan’s ambassador to the UN, had developed a doctrine to rationalize such behavior, claiming that right-wing authoritarian regimes were not as bad as totalitarian communist governments and, consequently, the United States could work with non-communist dictators who were favorably inclined toward the United States—even as they disappeared and tortured their own citizens and crushed dissent.

An unknown number—hundreds of thousands?—of civilians in these countries paid the ultimate price for this geostrategic dance with the devil(s). One notable and horrific example: Washington, looking to buttress anti-communist allies in Central America, financed and trained the military of El Salvador, which butchered 1,200 civilians at El Mozote in 1981 and engaged in other atrocities. Earlier, the National Guard there had raped and murdered four American nuns, and Archbishop Oscar Romero was assassinated after asking the United States to halt military aid to the country. (Elliott Abrams, then a senior Reagan administration official, helped cover up the El Mozote massacre. Today, he’s a top envoy for President Trump.) In nearby Nicaragua, the Reagan administration backed the Contra rebels fighting the nation’s socialist Sandinista government, disregarding reports of Contra human rights abuses and drug running. (The Sandinistas in 1979 had overthrown the corrupt and tyrannical reign of Anastasio Somoza, who had ruled with American support.) Washington gave a green-light to bloodshed, torture, and corruption around the world—for corruption, see the case of Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire—as long as the perps claimed to be part of the war on communism. And it fixated on Fidel Castro in Cuba, continuing a decades-old economic blockade that failed to dislodge the communist dictator but that did punish the people of Cuba.

In this environment of nuclear fear and bloody bargains, progressives such as Sanders looked for a way out. They sought to make citizen-to-citizen connections with countries in Washington’s crosshairs to diminish tensions and counter the demonization of these countries pushed by the hawks. So Sanders as mayor developed a “sister city” relationship with Yaroslavl, a Russian city of 600,000 on the Volga River. And he traveled there in 1988 shortly after he was married. (That’s why he referred to this trip as a “very strange honeymoon.”) He visited Cuba in 1989 and proposed a sister-city relationship with Havana. And in 1985, he traveled to Nicaragua, as a fierce opponent of the Contra war, at a time when many Americans and many Democrats in Congress also opposed the Reagan administration’s support of the Contras.

Sanders’ particular actions and statements related to these visits are fair game. Was he too soft on Castro? Sanders did seem mostly focused on advances in literacy and health care in Cuba since Castro and his rebels booted out the brutal military dictator Fulgencio Batista. After returning from Cuba in 1989, Sanders told a local Vermont paper that Cuba “is not a perfect society” but that he saw merit in the Cuban argument that Americans could not be truly “free” in a society with homelessness and hunger. “The question is how you bring both economic and political freedom together in one society,” Sanders said. And he hailed the Cuban revolution for encouraging people to work for the common good and noted that in a region where many people are oppressed and starving, “Cuba is a model of what a society could be.”

While in Nicargaua, Sanders attended a rally, where the audience chanted, “Here, there, everywhere, the Yankee will die.” (Sanders has said he did not remember hearing this anti-American chant.) But his trip to Nicaragua was part of what he had described as an effort—”in at least some small way”—to “play a role in reversing President Reagan’s policies in Central America” and ending the war there.

Sanders’ trip to the Soviet Union is easy to mock. There is video of him dancing and also—shirtless—singing “This Land Is Your Land” to his hosts after a stint in a sauna. But this visit was motivated by a concern similar to what had led him to Nicaragua. As Sanders explained a year before making that trek, “By encouraging citizen-to-citizen exchanges—of young people, artists and musicians, business people, public officials, and just plain ordinary citizens, we can break down the barriers and stereotypes which exist between the Soviet Union and the United States.” Upon his return, he pointed out positive elements of Soviet life he had witnessed—after-school programs, low rents—but he also acknowledged the down sides (problems with food availability, antiquated medical technology).

It is true that during and after these trips Sanders did not assail the governments of these countries or denounce their repressive ways. He did not blast away at the Soviet, Cuban, and Nicaraguan regimes. (At the time, Daniel Ortega, then and now the leader of Nicaragua, was not yet the corrupt autocrat he later became.) Sanders, like many progressives at the time, was looking to make connections in the countries targeted by the Reaganauts and create a citizens’ foreign policy. He was attempting to subvert those Reagan policies that exacerbated conflict, intensified the arms race, contributed to violence and human rights abuses, and financed wars. In the case of Nicaragua, Congress restrained Reagan’s efforts to assist the Contras. But then the White House arguably broke the law by secretly funneling aid to the Contras, which included the funds raised by its covert and also arguably illegal sales of arms to Iran.

None of this is to say Sanders made the right judgments in every instance. He probably swung too far in the other direction while attempting to counter the ends-justify-the-means Cold Warriors. (An editorial in a Vermont paper called Sanders “a long-time admirer of Fidel Castro and what he has done for the Cuban people.” Sanders did say at the time that he wanted to meet Castro, who clearly was a dictator.) At the time, as progressives justifiably criticized Reagan’s policies regarding Nicaragua, Cuba, and the Soviet Union, there was a tendency within some quarters of the left to be too forgiving of Castro, the Sandinistas, and others and an inclination not to dump on regimes in Latin America and elsewhere that were opposing US interventionism. That’s something that Sanders has to address (even as Trump gets away with making nice with tyrannical brutes around the world, including Vladimir Putin, Kim Jong Un, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Rodrigo Duterte, Mohammed bin Salman, and others).

Sanders’ interactions with these nations and his remarks from those days are part of a larger tale. He was a committed foe of the Cold War and its hawks. Opposing Reagan’s secret and not-too-secret wars in Central America and elsewhere was virtuous. Looking to diminish the tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States with people-to-people diplomacy was commendable. In these endeavors, Sanders was on the right side of history. But as with some on the left, Sanders did not focus on the anti-democratic foundations of the Soviet Union and Cuba, in part because the Cold Warriors themselves were already demonizing these societies in war-mongering fashion. Consequently, Sanders is now vulnerable to slashing and simplistic attacks that depict him as a sucker for lefty dictators. The world—then and now—is far more complex than that. But if this assault continues, the challenge for Sanders will be to explain his positions of the past and convey the larger myth-busting story of the Cold War—which is tough to do in short sound bites or on a chaotic debate stage. And doing so may well become a big—and an appropriate—test for this presidential candidate.