Immigration court in New York CityErik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty

An unprecedented joint coalition of immigration judges, immigration attorneys, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement employees asked Tuesday to “immediately and temporarily close all immigration courts nationwide” in the face of the coronavirus pandemic.

The courts, run by the Department of Justice, have remained open—even as local governments have shut down other courthouses and the US Supreme Court decided to temporarily suspend business out of concern for the health of the public and employees.

“We are calling on DOJ to do the right thing now,” said Ashley Tabaddor, president of the National Association of Immigration Judges union, on a press call Tuesday. Tabaddor and other members of the coalition spoke with a clear message: Keeping immigration courts open puts court employees, government trial attorneys, private counsel, judges, and the public at risk of infection.

On Friday, DOJ announced that it would shut down only the immigration court in Seattle, which has been particularly hard hit by the coronavirus. It also put an end to group immigration hearings in a few big cities but kept all other locations operating as usual. Two days later, on Sunday, DOJ suspended all group hearings across the country—save for those involving asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border.

That same day, the unlikely alliance of judges, attorneys, and ICE employees publicly called for the nationwide “emergency closure” of the more than 60 immigration courts. They said DOJ’s response to the pandemic was “insufficient and not premised on transparent scientific information.”

“No doubt, closing the courts is a difficult decision that will impose significant hardship for those in the Migrant Protection Protocols and detained Respondents. But these are extraordinary times,” the letter read. “Respondents who are in detained settings are in a particularly vulnerable situation that warrants specialized considerations.”

As it stands, the group hearings under the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) or “Remain in Mexico” policy are still happening, meaning hundreds of asylum seekers continue to line up every day at US ports of entry, sometimes as early as 3 or 4 a.m., to be processed by Customs and Border Protection agents and transported by bus to courtrooms in border cities such as San Diego for their day in court. These hearings put up to 50 people—many of them families with small children—in a courtroom for hours at a time and countless more in crowded courthouse waiting rooms.

After reporting in January on MPP hearings in San Diego, I can say with some certainty that these conditions aren’t conducive to the social distancing health experts have said is necessary to prevent wider spread of the coronavirus. The coalition said in its call Tuesday that there should be an end to all MPP hearings now.

Robyn Barnard, an attorney with Human Rights First who like other immigration attorneys has taken her frustrations with DOJ to Twitter, told me Tuesday morning that she’s trying her best to update her MPP clients in San Diego on what the courts decide during this crisis. “They’re taking precautions to try to care for themselves and their children, but all they’ve heard is, ‘You have to show up to your hearing.’ There hasn’t been any information sent out by the US government to that population at all,” Barnard said. “Even for immigration attorneys, we’re getting our updates from Twitter from the EOIR account. There hasn’t been very effective or widespread information, so I think that the MPP populations is down on their list of priorities.”

Barnard told me that closing down the immigration court buildings is the responsible thing to do but that postponing MPP hearings could also put vulnerable people in more danger by forcing him to remain in Mexican border cities for longer periods of time. (Most people already have to wait months before their first appearance in front of a US judge.) But Barnard said DHS has the authority to allow asylum seekers to be paroled into the country if they’ve been victims of violence, have health risks, or are from more at-risk populations.

There’s been talk of holding some hearings via phone or telephone, Barnard said, but for now, there’s a consensus among judges and attorneys that there needs to be a closure—especially because there have been attorneys and a judge who have showed coronavirus symptoms and who are self-quarantining.

I asked the Executive Office of Immigration Review, a branch of DOJ that oversees the courts, why MPP group hearings were still taking place in courtrooms near the border if all other group hearings have been canceled. I was directed to contact the Department of Homeland Security if I had questions about the program. (I emailed DHS but did not receive a response before publication.)

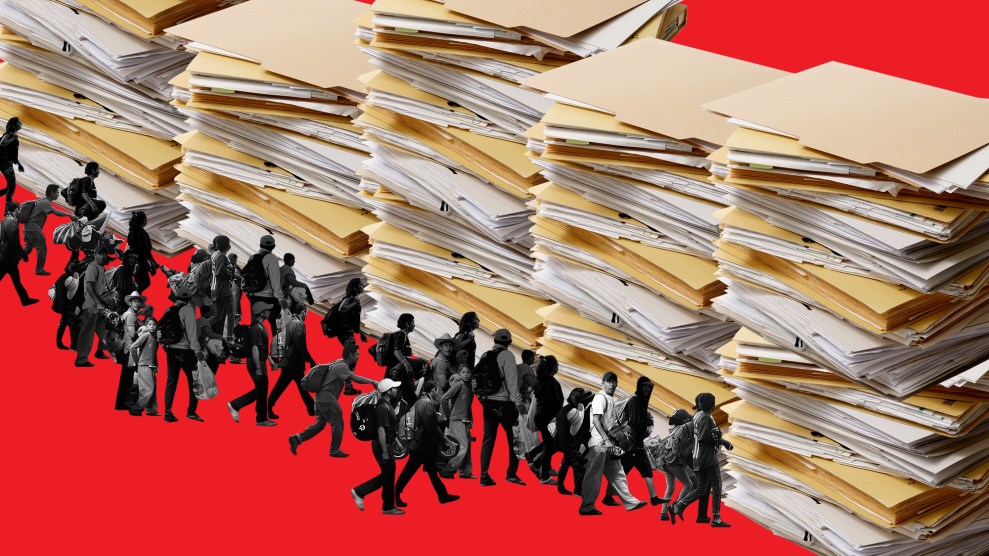

“The fact that we had to team up to request EOIR to close the courts speaks for itself,” said the American Immigration Lawyers Association’s Jeremy McKinney, who noted the Trump administration has been pushing immigration judges to meet high quotas and clear a backlog of cases that has passed the 1 million mark. Politics are guiding this decision-making, he said—“not science.”

“We don’t understand their logic,” said Fanny Behar-Ostrow, president of the American Federation of Government Employees Local 511, the union representing ICE trial attorneys. She said Tuesday that when the government shut down in 2019, immigration courts were put on pause, and the only hearings that continued were for those inside detention facilities. Yet, in the middle of a health crisis, government attorneys “are being required to appear in person to all hearings,” she said, adding she’s been “inundated with emails and calls” from employees concerned with their safety.

For now, Tabaddor says her union is trying to empower judges to use their authority to allow more telephone appearances and also call in sick themselves. “I’ve had a lot of judges who have reached out to me with a lot of anxiety and panic,” she said, “and they are in no position to make decisions on people’s lives.”