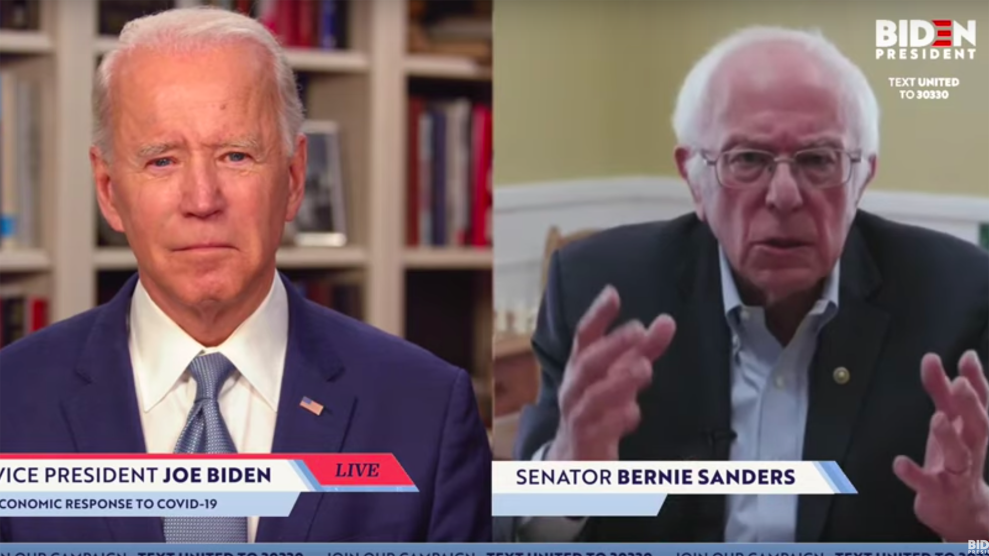

Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden participate in a Democratic presidential primary debate on Sunday, March 15, 2020, in Washington.Evan Vucci/AP

A mere 24 hours after Bernie Sanders called it quits on his second presidential run, the Vermont senator’s youthful supporters had a message for Joe Biden: Don’t let us down.

“We need you to champion the bold ideas that have galvanized our generation and given us hope in the political process,” said a letter from the #EarnOurVote initiative, a coalition of eight youth-focused groups, including the Sunrise Movement, March for Our Lives, and Justice Democrats. Their four-page memo outlined the “commitments” the former vice president—who failed to win much support from voters under 45 during the primaries—should take up in the general election campaign to “earn the support of our generation and unite the party.”

One of their main requests: that Biden appoint ardent progressives to key executive branch positions. The groups want left-of-center lawmakers who endorsed Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren to co-chair Biden’s transition team; they want liberal economists like Joseph Stiglitz to serve on Biden’s National Economic Council; and they want a “trusted progressive” to run the Presidential Personnel Office with the aim of keeping a Biden administration “free of corruption.” They also wanted Biden to refrain from appointing any “current or former Wall Street executives or corporate lobbyists, or people affiliated with the fossil fuel, health insurance, or private prison corporations, to your transition team, advisor roles of cabinet.”

The document is the first high-profile manifestation of an organized effort among progressive activists, scholars, and lawmakers that quietly came together over the last few weeks as Biden—not Sanders—salted away the Democratic nomination for president. The distaste many on the left have for the former vice president’s candidacy stems from his ties to the banking industry and centrist economists, among other things. Now that Biden is moving ahead to the general election, progressives are determined to exert what power they have to shape his future appointments.

In 2008, liberals felt they’d been steamrolled by the Obama transition, which unfolded largely without their input. The team installed Clinton-era neoliberals such as Timothy Geithner and Larry Summers into high-level roles, in which capacity they were in turn given the keys to the recovery from the Great Recession.

Eight years later, progressive groups had armed themselves for an ideological battle over the make-up of the would-be Clinton administration. The Roosevelt Institute, a liberal think tank, had built a bench of 150 candidates for critical economic policy jobs under Clinton. The Revolving Door Project, a progressive watchdog group that tracks corporate influence, dug into potential appointees it found undesirable based on their connections to business interests. Elizabeth Warren had brought Clinton her own list of potential appointees. Sanders, meanwhile, chose to spend the capital he’d accumulated in his formidable primary fight on changes to DNC rules that he believed would level the playing field for party outsiders like himself.

Clinton, a policy wonk at heart, ultimately left little room for influence when it came to her potential appointees. But progressives were heartened by some of her choices, such as inequality expert Heather Boushey, the chief economist at the left-leaning Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Clinton had tapped her as the chief economist on her transition team and her likely pick to lead the White House’s National Economic Council.

At first blush, Biden’s long political career and Obama ties might make him seem like a worst-case scenario for progressives who want to exert some influence. He’s spent nearly five decades at the highest levels of federal elected office, and his team had been intimately involved in the 2008 Obama transition that many on the left decried. But the former vice president ran a campaign that, for the most part, remained ideologically agnostic and scant on policy details. That, in combination with his White House experience, may actually set the table well for progressives hoping to exercise some control, says Chris Lu, who served as a deputy secretary of labor during the Obama administration and executive director of the Obama–Biden transition.

“Biden’s team knows it’s not just about the 100-day legislative strategy—they know he needs a regulatory strategy around what Trump regs need to be turned around, and a budget, which is usually unveiled sometime in February,” Lu explains. “That’s to the benefit of the progressive community, because a lot of their ideas can be translated more readily by folks who understand the process.”

There are also some signs that Biden wants to cooperate with the left. Last month, Biden adopted Elizabeth Warren’s bankruptcy proposal, a plan that would reverse much of the 2005 bankruptcy bill he had championed as a US senator. As progressive youth groups released their list of demands last week, Biden announced that he supported dropping the Medicare qualifying age to 60 and canceling student debt for some low- and middle-income students—modest overtures to the progressive activists. And on Monday, Sanders and Biden announced that their trusted advisers would team up on six policy “task forces” focusing on topics such as the economy, climate change, and criminal justice, an effort the Biden campaign says will lay the groundwork for Biden’s general election platform and presidential transition.

So far, the reception among liberal leaders and Sanders loyalists has been flat. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), who had endorsed Sanders, told the New York Times that Biden’s concessions were “almost insulting” in their meagerness. Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), who co-chairs the Congressional Progressive Caucus, told the Times she needs to see “real movement” from the former veep.

Lu has been in touch with a number of the progressive groups seeking advice on how to have a say in Biden’s appointees. He’s encouraged them to think about positions that touch a lot of decisions, such as those in the Office of Management and Budget and the National Economic Council. He also says they should consider whom they might want named to lower-level positions beyond the Cabinet. “Everyone sort of thinks about the Cabinet—and the Cabinet is important,” Lu says, “but who runs NOAA, for instance, can send an important signal about climate change priorities, and if you want something done on workers’ rights, you need someone at OSHA who gets it.”

Other important players are reprising some aspect of their 2016 roles. The Roosevelt Institute—to which a pair of former Warren policy aides, Julie Margetta Morgan and Bharat Ramamurti, recently decamped—has been reaching out to experts, sources familiar with their work tell Mother Jones, but the think tank isn’t currently performing the same bench-building effort it undertook in 2016. “We believe it’s important to have progressive, reform-minded personnel that are ready and able to use the full power of the government to make a difference in people’s everyday lives,” said spokesperson Ariela Weinberger when asked about the early outreach.

The Revolving Door, led by Jeff Hauser, is working with allied groups to identify people they’d prefer that Biden not appoint to his administration. Among those on Revolving Door’s no-fly list: Larry Fink, chair and CEO of the financial services behemoth BlackRock, who Biden donors floated as a Treasury pick at a recent fundraiser; Erskine Bowles, a former Bill Clinton chief of staff who co-chaired an Obama administration task force that called for cuts in benefits for the elderly, veterans, and government workers; and Jeffrey Zients, Obama’s final director of the National Economic Council who now serves as president of the Cranemere Group, a London-based private equity firm. He’s a bundler for the Biden campaign and, during his White House tenure, Zients had been a proponent of austerity. “I fear he might be this generation’s Robert Rubin,” Hauser says, referring to the finance-friendly Clinton administration Treasury secretary.

One remaining question is what role Elizabeth Warren’s will play. The Massachusetts senator has remained front and center in the debate over the nation’s response to the coronavirus pandemic, releasing plans to safeguard the economy and protect voting rights. She endorsed Biden on Tuesday, but has yet to announce any formal collaborations with the former vice president.*

But there’s reason to believe she may reprise her 2016 efforts. Don’t forget that Warren’s entrance into national politics came by way of her feud with Biden over bankruptcy legislation in the aughts. She was a Harvard bankruptcy professor, then, and Biden was a senator whom she accused of performing “energetic work on behalf of the credit card companies.” In those days she saw him as a man from whom working families needed to be protected. Now he’s the standard-bearer of the party that wants to speak for them.

*This story has been updated to reflect Elizabeth Warren’s endorsement of Joe Biden.