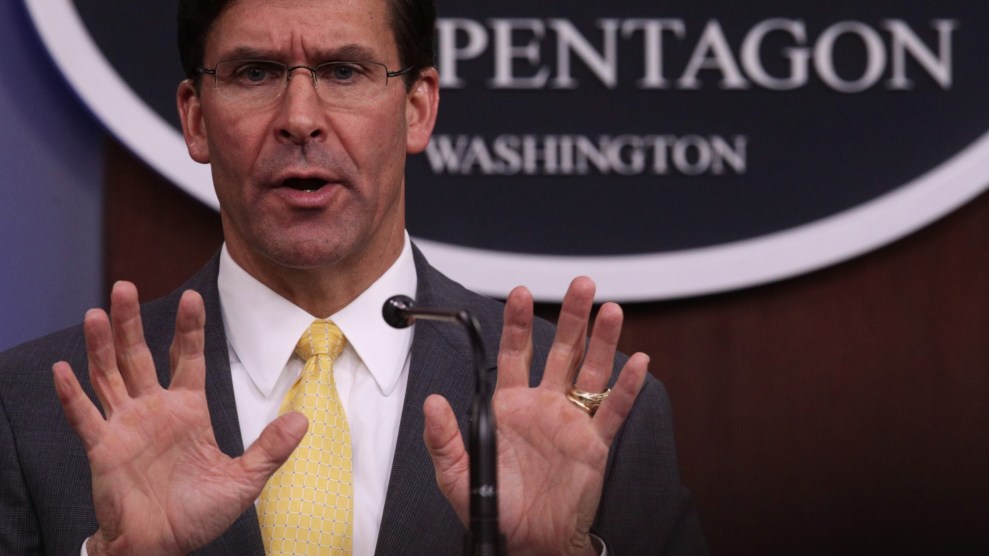

Secretary of Defense Mark Esper addresses the press from the Pentagon's briefing room.Alex Wong/Getty

While nearly everyone was focused on the accelerating coronavirus outbreak, the Defense Department has spent the last few weeks quietly boosting lobbyists and clamping down on information normally released to the public—including the number of people in the military who have contracted COVID-19.

On Monday, the Pentagon ordered military installations across the globe to stop revealing new cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, among its staff. Using a familiar excuse, Pentagon spokesperson Jonathan Hoffman cited national security as a reason to conceal these local figures that the Pentagon had been regularly releasing for days. In a statement, he said the military would “understandably protect that information from public release and falling into the hands of our adversaries—as we expect they would do the same.”

Reporters have grown used to this type of behavior from the Pentagon. Under James Mattis, Trump’s first secretary of defense, the Pentagon was harshly criticized for its lack of press briefings and its decision to stop reporting the number of US troops in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. Mark Esper, the ex–Raytheon lobbyist whom Trump tapped in July as Mattis’ permanent replacement, has continued the worrisome trend, often in ways that aren’t immediately noticeable.

Around this time of year, lawmakers would normally be in the early stages of drafting next year’s defense spending authorization bill, one of the few pieces of legislation Congress must pass each year. Before the bill is assembled on Capitol Hill, the Pentagon puts together its own legislative proposals, and with Congress focused on stemming the spread of COVID-19 and shoring up the economy, the Pentagon included several curious requests this year that would benefit defense lobbyists and shield Pentagon spending projections from oversight.

The first one, which Steven Aftergood at the Federation of American Scientists flagged on Monday, asks lawmakers to let the Pentagon classify its future defense spending plans. This extraordinary move would eliminate an important area of oversight for Pentagon watchers, who have relied on these projected figures since 1989, when a federal law required the Defense Department to annually produce them. For journalists, the appeal is obvious: What better way to align the Pentagon’s spending requests with its actual needs than by looking at the department’s own predictions?

Evidently the department does not agree. In a letter to Congress, officials cited two reasons for concealing these spending plans from the public: Their release could help defense firms get a leg up when competing for government contracts, and the plans “might inadvertently reveal sensitive information” and “cause serious risk to the national defense.” That’s lunacy to anyone who follows the debate over the Pentagon’s budget each year, where reams of information are made public in relation to the department’s spending request. Information that is especially sensitive, such as projected spending on the intelligence agencies, has usually remained classified, but the Pentagon’s unclassified projections are regularly used by government watchdogs to inform the public debate surrounding the massive sums of money the United States spends on national security, which the nonpartisan Project on Government Oversight (POGO) estimated to be roughly $1.21 trillion last year.

These future projections are vital to informing the public, but it’s worth noting that the Pentagon has partially shielded them in the past. Barack Obama’s first defense budget didn’t include detailed projections. The Trump administration’s first budget, from fiscal year 2017, didn’t either, but they at least had a somewhat valid excuse. Future defense spending projections at the time were in flux as the government prepared the release of a series of defense strategy documents like the Missile Defense Review, Defense News reported at the time. But all those reports have since been released and the last two Pentagon budget requests both contained these figures. Why is the Pentagon suddenly making this an issue again?

Gordon Adams, a Clinton White House official who has written extensively about defense spending, told me the request was “part of a broader story about the extent to which the Pentagon is cutting off information to the Congress and the public.” A reduction in press briefings and concealment of spending projections aren’t the only results of the Pentagon’s war on transparency. Stars and Stripes, an independent military publication that has provided indispensable reporting on the Pentagon’s response to the coronavirus outbreak, might be on the chopping block too. In the department’s budget proposal for fiscal year 2021, the Pentagon recommended stripping the outlet of $15 million in federal funding, which would cut its budget in half.

A different legislative proposal released by the Pentagon in recent weeks would have Congress narrow the definition of lobbying, which would help former Pentagon officials like Esper get lucrative jobs in the defense industry after leaving government, and hurts watchdogs who wish to track how special interests influence defense policy. POGO’s Mandy Smithberger, who first noticed that request and wrote about it on Wednesday, told me the provision would clear the way for more defense officials to take roles in “strategic consulting” and “business development,” which tend to involve lobbying-related activity. “The definition of lobbying was getting closer to common-sense understanding of what lobbying really is,” she said. “This proposal is trying to get it back to a pretty bare-bone definition that’s full of loopholes.” Even Donald Trump has made this exact same point. In October 2016, then-candidate Trump released a five-point plan to “drain the swamp,” which included a provision “to expand the definition of lobbyist so we close all the loopholes that former government officials use by labeling themselves consultants and advisors when we all know they are lobbyists.”

Last year’s NDAA fight provided another opportunity to strengthen these ethics rules—and House Democrats did add several provisions doing so—but nearly all of those additions failed to survive the Republican-controlled Senate.

The dearth of transparency around lobbying is concerning no matter who runs the Pentagon, but especially so with Esper, given his time lobbying for Raytheon. Under heavy questioning from Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), who unveiled a plan to crack down on the Pentagon’s revolving door with industry as part of her presidential campaign last year, Esper refused to recuse himself permanently from issues involving Raytheon or commit to other stringent ethics requirements, even the ones adopted by former Deputy Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan, who entered government after a lengthy career at Boeing.

Since taking over, Esper has continued Mattis’ policy of closing the department to the press. After a series of Iranian missile attacks in January caused dozens of US troops to be diagnosed with traumatic brain injuries, the Pentagon repeatedly delayed and adjusted its reports of how many Americans were affected, raising concerns over how forthright military officials had been when initially reporting the injuries. Now it appears to be adhering to the same playbook when it comes to reporting COVID-19 infections at military bases and installations.

Moves like this remind Adams, he said, of “what the Soviets used to do”—making it “harder and harder to track defense actions, plans, and spending.”