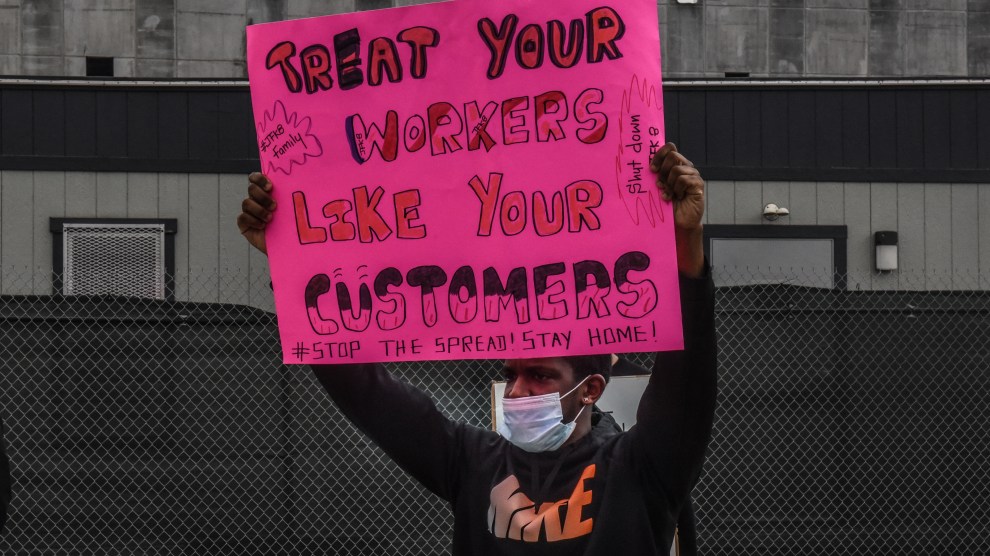

A worker protests labor conditions outside of an Amazon warehouse on May 1, 2020, in Staten Island. Stephanie Keith/Getty Images

On Monday, Tim Bray, an Amazon vice president, wrote a scathing letter announcing he was leaving the company over its “chickenshit” decision to terminate employees who have recently advocated for better working conditions. “I quit in dismay at Amazon firing whistleblowers who were making noise about warehouse employees frightened of Covid-19,” Bray’s letter opened.

Amazon has has defended its decision to fire the workers, and told outlets like Vice’s Motherboard that employees raising concerns about dangers at work are “spreading misinformation and making false claims.” In his letter, Bray called the company’s justifications for the firings “laughable.”

“It was clear to any reasonable observer that they were turfed for whistleblowing,” he wrote, before remarking on something else: “I’m sure it’s a coincidence that every one of them is a person of color, a woman, or both. Right?”

It’s probably not a coincidence. Firings of workers of color, women, and LGBTQ staff have been a larger trend at tech companies finding themselves responding to workers organizing for better conditions.

Each of the employees Amazon has fired over the past several weeks who have been involved in labor activism—Courtney Bowden, Gerald Bryson, Maren Costa, Emily Cunningham, Bashir Mohammed, and Chris Smalls, according to a list in Bray’s letter—have all been persons of color, women, or both.

This past fall, when Google fired five employees who were trying to organize a union, three of them were trans women; another was LGBTQ.

“It is incredibly bizarre,” Kathryn Spiers, one of the fired Google employees, said at the time. “I think Google was targeting more vulnerable members of the community.”

Only one of the 11 employee organizers who were fired by the two companies in these recent incidents was a straight, white man. The rest were people of color, women, and LGBTQ individuals. The firings’ impact on minority workers is magnified when compared to the technology companies’ overall lack of diversity—Google’s workforce, for example, is 54.4 percent white and 68.4 percent men, according to numbers it publishes. Amazon has a similar breakdown, however, its warehouses, where the six fired employees worked, are more diverse.

The firings could reflect a number of unflattering things about the companies, including that they run anti-unionization efforts that target the most vulnerable members of their workforce, or that their treatment of its workforce spurs its most vulnerable members to organize. Neither option would speak well to how technology companies are treating marginalized peoples. The company did not respond to my request for comment.

In his own case, Christian Smalls, one of the first Amazon organizers fired while advocating for better labor conditions during the coronavirus crisis, thinks that racism played a part.

“From all the evidence, it seems that way,” Smalls, who is black, said on the phone when asked if women and people color had been targeted at Amazon.

An internal memo obtained by Vice News revealed the company’s plans to smear Smalls, and that its general counsel, David Zapolsky, had called him “not smart or articulate.”

“It is borderline racism. That remark definitely lingers in the black community. They consider us not smart, not educated, not well-spoken,” Smalls said. “We can only imagine what types of conversations they had in private. We only heard what was leaked in the memo. That could be just a watered-down version of the conversations they actually have about minorities.”