H. Drew Galloway, executive director of MOVE Texas, spends his life trying to register young voters. Typically, in the spring of an election year, Galloway would be overseeing a staff of about four dozen who, before classes end for the summer, register newly eligible voters on 55 college campuses and at dozens of high schools.

Last year, MOVE Texas signed up more than 25,000 new voters. It reached nearly 8,000 more this year before the state’s March 3 presidential primary. But then the coronavirus outbreak scattered students, and MOVE Texas, like every other political group, suspended in-person registration drives. “We’ve gone from registering 2,000 people a week to registering maybe 100,” Galloway told me in April. “Voter registration is decimated in Texas.”

Even before the pandemic, Texas was a hard place to register. As of May, it was one of 10 states with no way to do so online. Anyone who wants to sign up voters must be deputized by each county they work in, every two years. Texas has an estimated 5.5 million unregistered but eligible voters—more people than the individual populations of 28 other states. The majority of them, according to the Texas Democratic Party, are young, people of color, or both, who would likely favor Democrats if they voted. Luke Warford, who directs the party’s efforts to expand voting, told me that Texas Democrats had hoped to see 2 million new people register this year as part of its push to tip the state blue. “We had plans to run the largest statewide voter registration program in history,” he said. “Introduce a pandemic and that makes everything you were planning to do in person quite a bit more difficult.”

Even if new voters succeed in registering, without changes to the existing system they’ll face unequal access to mail-in ballots. Texas limits mail-in voting for those under 65 to people who are out of town during the election, in jail, or have a “sickness or physical condition” that prevents them from going to the polls. Meanwhile, any voter 65 or older—the strongest age demographic for Donald Trump in 2016—can request an absentee ballot with no questions asked.

In April, a state judge ruled that people afraid of contracting the coronavirus while voting had a legitimate reason to get an absentee ballot. Texas’ Republican attorney general has opposed the ruling, claiming that “a fear of contracting COVID-19” is “an emotional condition and not a physical” one, and has raised the prospect of “criminal sanctions” for groups like MOVE Texas that help voters under 65 obtain mail-in ballots. In late May, the state’s all-Republican Supreme Court agreed a lack of immunity to the virus alone was not a valid reason, but said voters could weigh their health history and make their own decision—a ruling that could cause confusion and leave some people requesting mail ballots open to prosecution. A separate appeal on the matter is pending in federal court.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

What’s happened in Texas is happening nationwide: The coronavirus has heightened the already considerable obstacles blocking citizens from exercising their right to vote. In the last decade, Republicans have enacted new voting restrictions in 25 states. The Supreme Court has gutted the Voting Rights Act, unleashing new efforts in states with long histories of voting discrimination to make it harder for voters of color to cast ballots. And then there are the Russians, who attempted to access election infrastructure in all 50 states in 2016, and could try again. “What you’ve done with coronavirus,” said Marc Elias, the leading Democratic voting rights lawyer, “is you’ve added one more huge stressor to a system that was already at the breaking point.” The risk of mass voter disenfranchisement is greater in 2020 than at any time since the era before the abolition of poll taxes and literacy tests in the 1960s.

Voter ID laws are far more discriminatory when Department of Motor Vehicle offices are shuttered. Purges are more harmful when removed voters cannot easily reregister. Limited polling places and five-hour waits are especially pernicious under the threat of viral infection. And voter registration and traditional get-out-the-vote efforts have stalled. “Souls to the Polls” drives led by Black churches have been put on hold. States have delayed primaries and severely reduced or wholly eliminated in-person voting. Few are prepared to handle a surge of mail-in ballots in November. Democrats worry that COVID-19 could be weaponized to the GOP’s advantage, locking in an older and whiter electorate that stems the impact of demographic change.

“Coronavirus has added this additional layer of voter suppression to everything. The barriers that those laws put up are even higher now,” said Galloway. “That’s directly going to affect communities of color, low-income communities, young people.” The numbers are startling: In Kentucky, for example, where Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell is up for reelection, just 504 people registered in March compared to 7,256 the month before. In key states like Texas, Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia, the number of new voters who registered in March was half or less than it was during the same time period in 2016.

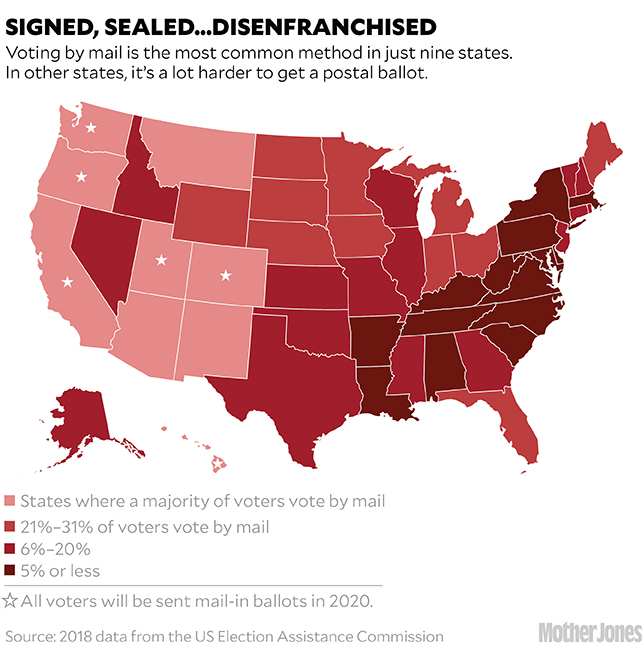

Public health and election experts agree that voting by mail is the safest way to cast a ballot in a pandemic. Yet most states are unprepared to hold mail elections in a way that won’t lead to significant voter disenfranchisement. The six best-positioned states—California, Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah, and Washington—have already put in place systems where a ballot is sent to every registered voter. In three other Western states—Arizona, Montana, and New Mexico—a majority of votes are cast by mail, according to data from the federal Election Assistance Commission. With Florida and pockets of other mail-in voters added in, a quarter of Americans voted by mail in 2018, a record number. But in the 40 other states, mail-in ballots made up just 9 percent of votes cast. Fewer than 8 percent of people voted by mail in key states like Texas, Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

“Because it’s been a minor method of voting in a lot of the key states, the rules and practices involving mail voting have gotten less scrutiny and haven’t been thought out to make sure they’re fair and accessible,” said Wendy Weiser, director of the democracy program at the Brennan Center for Justice.

While quickly expanding voting by mail could help many people cast ballots in November, it poses its own risks. If election officials, especially in places unused to the method, are overwhelmed by a surge of requests, ballots might not reach voters in time. The United States Postal Service, which faces a major budget shortfall and attacks from the Trump administration (a major fundraiser for the Republican National Convention was just named postmaster general), could lack the resources to handle increases in sent and returned ballots. And a sizable chunk of the electorate will be unfamiliar with the intricate rules governing mail-in voting and could see their ballots thrown out on technicalities.

Florida’s 2018 election presents cautionary tales, both about how unrelated events could disrupt mail-in voting and how postal ballots can be invalidated. About a week before the contest, Cesar Sayoc, a fervent Trump supporter, was arrested for mailing explosive devices to prominent Democrats including Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama. Five packages were traced to a large postal distribution center in Miami’s industrial outskirts near where Sayoc was living, forcing staff to evacuate. The coming weeks saw widespread reports of delayed or missing ballots among South Florida’s heavily Democratic voters. While the USPS says an internal review found ballot handling was not hindered by the evacuations, local journalists reported concerns that the facility was too short-staffed to tackle the flood of election mail. Democratic voters in Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties, who make up the party’s core support in the state, were sent almost twice as many absentee ballots as Republicans, but 144,000 of the Democrats’ ballots were never returned or didn’t arrive back in time. Republican Ron DeSantis was elected governor by 32,000 votes; Rick Scott, also a Republican, won a US Senate seat by 10,000 votes.

While nearly a third of Florida voters cast mail ballots in that election, some core Democratic constituencies were far more likely to have those votes thrown out, even when ballots were returned in time to be counted. Mail voters in Florida, who voted without the assistance of poll workers, had nearly 32,000 votes tossed over small mistakes like a forgotten envelope signature or because officials concluded a voter’s signature did not match one on file. Voters who were 18 to 21 had their ballots rejected more than eight times as often as voters 65 or older. Black, Hispanic, and other voters of color were more than twice as likely as white voters to have mail-in ballots rejected. Overall, Florida’s mail voters were 15 times more likely to have ballots thrown out than in-person voters. In 2018, 1.4 percent of mail-in ballots cast nationwide were rejected. If that rate holds in 2020 and half the country votes by mail, about 1 million ballots would be tossed—enough to swing the outcomes in key states.

While groups like Rock the Vote and Voto Latino have reported a major increase in voter registrations amid the protests over George Floyd’s killing by a Minneapolis police officer, calls for young people and people of color to reshape the 2020 elections by voting in record numbers must contend with the reality that those communities most affected by racism and police brutality could also have the toughest time voting this year.

“As we push more people to vote by mail, which is a good thing, the number of ballots that aren’t counted is going to increase. And we know those ballots are not equally distributed. This burden is shared disproportionately by young and minority voters,” Elias said.

Wisconsin’s disastrous election on April 7, when officials proceeded with a primary and state Supreme Court race despite a statewide shelter-in-place order, provided a vivid illustration of how not to vote during a pandemic. Republican leaders in the state legislature rebuffed calls by Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, to postpone the election or mail an absentee ballot to every registered voter. With many people afraid to leave their homes, and cities closing the bulk of their polling places because of poll worker shortages—Milwaukee opened just 5 of 180—anxious Wisconsinites were forced to wait hours in line to vote. Just 6 percent of the state’s voters cast ballots by mail in 2018; this spring around 60 percent did.

While photos of masked voters and poll workers in protective gear drew national outrage, they may have obscured the fact that the state was ill-equipped to handle that huge increase. Though officials worked around the clock—Madison’s city clerk said she logged more than 100 hours a week during the close of the election—121,000 mail-in ballots were not returned, as voters complained they didn’t receive them in time or at all, because of mistakes by election workers or the post office.

A spokesperson for the Wisconsin Elections Commission confirmed that the dramatic increase in absentee voting “certainly caught us by surprise,” conceding that Milwaukee and Green Bay, both home to many Democratic voters, had failed to get every requester a ballot, unlike “the vast majority” of the states’ 1,850 municipalities.

Wisconsin also shined a light on the restrictive rules for mail-in ballots. Voters had to get a witness to watch them fill out their ballots, difficult for anyone living alone at a time of social distancing. Many voters had to include a copy of their photo ID to request an absentee ballot, which at a minimum required uploading a picture of their ID or photocopying it. Such rules, which Republicans refused to waive, helped lead to an estimated 23,000 absentee ballots being rejected—almost the same number that Trump carried the state by in 2016.

Weiser said that Wisconsin “dodged a bullet in that the election wasn’t close.” In the state’s Democratic presidential primary, Joe Biden easily defeated Bernie Sanders, who suspended his campaign the next day, and progressive candidate Jill Karofsky won a hard-fought race for a seat on the state Supreme Court by 11 points. Weiser warned that the way voting took place exposed “a lot of gaps the system was not prepared for that will only be exacerbated in a presidential election.”

Indeed, only a third of adult Wisconsinites voted in the April elections. Turnout this November is expected to double that, pushed higher by young, first-time, and infrequent voters. “If 34 percent turnout strained resources close to the breaking point, what is 70 percent or more turnout going to look like?” Weiser wonders. “That really worries me.”

A number of states that held primaries in early June experienced problems similar to Wisconsin. In Washington, DC, where election officials ill-equipped to handle a surge in absentee ballots and polling places were cut, a larger-than-expected turnout saw in-person voters forced to wait up to six hours. In Maryland, where the governor issued an order to send mail ballots to every registered voter, a million ballots were delayed or never arrived. And in Pennsylvania, the huge volume of mail ballots created counting delays, especially in Philadelphia, that have left some 20 state races uncalled days after the election. Similar delays in November could be seized upon by Trump to attempt to discredit results that would otherwise see him removed from office.

Mail-in voting takes practice. Oregon, the first state to adopt all-mail elections in the 1990s, now boasts one of the country’s lowest ballot rejection rates and increased turnout of low-propensity voters, including young voters and communities of color. “The real tipping point is when most of your voters have done it and are comfortable with it,” said Phil Keisling, who served as Oregon’s secretary of state from 1991 to 1999.

But the state’s elegantly simple system—ballots are mailed to every active registered voter—is unusual. Many of the states most likely to decide the presidential election have substantial barriers to mail-in voting. In 16 states, mostly in the South and Northeast, to get an absentee ballot you must provide an approved reason, under penalty of perjury, why you can’t vote in person on election day. Nearly a dozen states have a requirement like Wisconsin’s that absentee voting be witnessed; Alabama goes so far as to mandate two witnesses or a notarized affidavit.

And many states don’t make it easy to get a ballot or have it counted. Thirty-one states do not offer a way for all citizens to request an absentee ballot online, forcing voters to mail forms to county registration offices. And 36 states don’t provide postage to return ballots, which functions as a de facto poll tax. In 26 states—including New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Virginia—election officials are not required to notify voters if there’s a problem with a received absentee ballot, such as a missing or mismatched signature, before throwing it out.

Despite Trump’s false claim that mail-in voting benefits Democrats, the parties’ voters made roughly equal use of the option in 2016, and it’s helped Republicans in key swing states like Arizona and Florida. Older and whiter voters tend to vote by mail more than the overall electorate. According to a Brennan Center analysis of voting in seven presidential battlegrounds, voters 65 or over were roughly twice as likely to vote by mail than those under 40. Nationwide, in 2018, just 11 percent of Black voters cast ballots by mail while 23 percent of white voters did.

Trump and the RNC have signaled they’ll fight expansions of mail-in voting that would make the process more accessible for younger and more diverse voters, but not for their most reliable voters, such as mailing absentee ballot applications to anyone over 64.

Ben Wikler, who helped thousands of voters cast their first mail-in ballots in April as chair of the Wisconsin Democratic Party, warns that “the danger is Republicans will apply the ruthless cynicism they’ve used for in-person voter suppression to absentee voter suppression and we’ll be fighting against a whole new set of tactics.”

Another worry is the spread of disinformation about how to vote, which could be particularly disruptive in a year when Americans will have to adopt unfamiliar procedures. The potential methods go well beyond what’s known about Russia’s 2016 playbook. Shady political organizations could send people genuine-seeming but fake absentee ballots, set up bogus websites to trick people into thinking they’ve requested ballots, spread the wrong deadline for returning mail-in ballots, or give incorrect information about the type of documentation or identification needed to vote.

“The pandemic could likely be weaponized in the hands of those that already had the intent to suppress the vote,” said Vanita Gupta, president of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. “There are a lot more challenges now to conducting elections. There’s a lot more potential for mischief.”

“The silver lining” of Wisconsin, Gupta said, “was it raised the alarm for folks who weren’t necessarily focusing on the elections and democracy component of COVID. It certainly awakened local and state officials—they don’t want those same Wisconsin photos on their watch.”

Voting rights groups and Democratic lawyers have filed two dozen lawsuits challenging vote-by-mail rules, including laws that forbid counting ballots not received by Election Day or with mismatched signatures. “A lot of the litigation I’m doing is focused on how we remove those barriers, those friction points, in this overburdened system to ensure that everyone who casts a lawful ballot has it counted,” said Elias.

Advocates are urgently petitioning states to expand online registration to pick up demand created by shuttered DMVs, where people most often register. They are also rallying to have election administrators send ballots or, at the very least, absentee ballot applications, to all registered voters; preserve safe in-person options for communities that distrust mail-in voting; and ensure enough early voting, polling locations, and poll workers to allow voters and election officials to practice social distancing.

Doing all that will require a lot of money. It will mean hiring election workers, giving them protective equipment, buying new tallying machines for absentee ballots, and covering increased postage costs, while still having enough to open and staff polling places. The $400 million in aid to states that Congress allocated in its first economic recovery bill is “woefully inadequate,” said Gupta, who estimated that $2 billion or more is needed.

“If states only have the money they have now, we’ll see problems like we saw in Wisconsin,” predicted Weiser, “in 40 or more states and at probably much worse levels…It will be disastrous.”

The electoral response to the coronavirus mirrors the public health one, with little national leadership, and state action varying widely. Some states, like California, which is sending mail-in ballots to all registered voters, are doing a lot to make voting easier while others, like Texas, are fighting commonsense steps to expand voter access. Elements of the federal government and state-level Republicans may be working quietly to respond responsibly and ensure a free and fair election, but Trump is actively undermining that goal by lying about the prevalence of voter fraud and opposing mail-in voting.

The president’s disastrous handling of the coronavirus outbreak may have imperiled his reelection chances. But its disproportionate impacts could play to his advantage. The counties with the highest rates of covid-19 as of mid-April voted for Clinton by 19 points, while the areas with the lowest rates supported Trump by 15 points. If the virus surges or stay-at-home orders return for Election Day, residents of these large and staunchly Democratic cities could be afraid to vote in person—and in most states, they’ll face untested election systems with their own potentially decisive faults. As Wikler noted in the wake of Wisconsin’s primary, “The harder it is to vote, the more people wind up getting pushed to the side.”