Mother Jones illustration; Dr. Bronner's; Getty

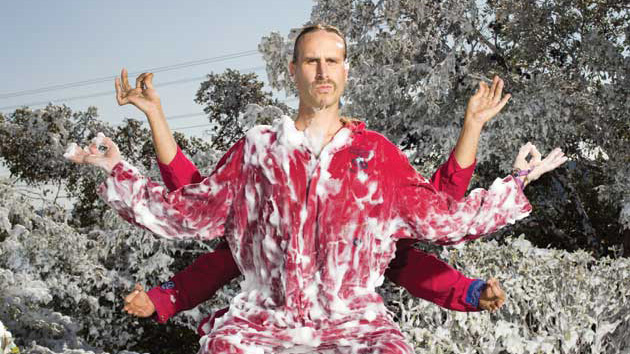

When I met David Bronner at a cannabis dispensary in Berkeley, California, last fall—approximately 1,000 years ago in the B.C., or before-coronavirus era—the CEO of Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soaps made good on my hunch that the Southern California company, known for its minty tingle and wordy label, is one of the few American corporations that give zero fucks.

In a good way.

I’d arrived at Berkeley Patients Group early, to get settled in before Bronner and his partner, Mia Hardwick, arrived. I recall thinking that if a doctor’s office and Hot Topic had a baby, this is almost certainly what it’d look like. The Misfits played overhead, almost, just almost pulling you out of the distinctly clinical and well-lit surroundings. Beneath the large glass display sat various types of cannabis flower, neatly arranged: Jack Herer, Biscotti, Gorilla Glue #4, Pineapple Punch.

Bronner showed up looking less the part of Company Executive than California Dude, in clay-colored, natural linen pants and a T-shirt, his long hair pulled into a ponytail and tucked under a cap. But it fit—his official title, after all, is actually “Cosmic Engagement Officer.” He had to hunch his over-6-foot frame to get a good look at the inventory.

“Could we check out a Brother David’s Pineapple Punch?” he asked the budtender.

She handed him a small, brown paper box. Like fresh juicy pineapples after an amazing day at the beach, a sticker on it read, Pineapple Punch is your cannabis partner for sunshine, freedom and creative flow. It boasted about being grown “under the California Sun,” “In the Soil of Mother Earth,” without chemicals, by fairly paid family farmers.

“I’ll actually go ahead and buy one. I already know it’s really good,” Bronner said, with a knowing smile.

He’s tried it, of course—likely many times. Pineapple Punch is a product from Bronner’s new(ish) cannabis line, Brother David’s. Launched on Earth Day last year, April 22, Brother David’s is an entity separate from the organic soap empire founded by David’s grandfather in 1948 and is a means to introduce to the market a chemical-free, fair labor, cannabis program created with help from Bronner, Sun+Earth Certified. Because marijuana is still illegal at the federal level, he explained to me, it can’t be legally certified as “organic,” a determination made by the USDA, and consumers are largely left without knowing which growers are pesticide-free or employ fair labor practices. Sun+Earth Certified aims to be that standard.

This type of outside-the-box innovation is something of an informal guiding principle for the guy behind Dr. Bronner’s; it’s almost quite literally that insufferable trope, Be the change you want to see. If the soap company needs something to make its products ethically and environmentally friendly, and that something doesn’t already exist (or it’s not currently legal), Dr. Bronner’s will actually make change happen.

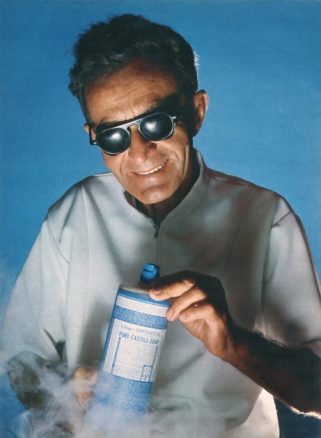

It’s practically baked into the company’s DNA: In addition to founding the company, Emanuel Bronner—aka “Dr. Bronner,” though he wasn’t really a doctor—held strong moral convictions. He gave lectures on the interconnectedness of humanity and sold soap in downtown Los Angeles. In 1950, after Emanuel realized people were simply taking the soap and leaving, he printed his sermons on the label. Dr. Bronner’s bottles still carry Emanuel’s message: “We are All-One or None!”

Over the years, Dr. Bronner’s has put in real work to make change happen, unlike so many brands now trying to capitalize on socially conscious consumers (see this piece from my colleague Inae Oh from earlier this week if you don’t know what I mean). The self-described “activist” brand has put its weight behind causes like animal welfare, criminal justice reform, and fair pay. It has spent millions in support of state ballot measures that require the labeling of genetically modified foods. Back in 2001, Dr. Bronner’s helped lead a lawsuit against the Drug Enforcement Agency to allow oil derived from hemp in their products, eventually notching a win at the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in 2004. Bronner himself has been arrested twice for hemp-related protests: First for planting hemp seeds on the lawn of the Arlington, Virginia, DEA Museum in 2009, and then again in 2012 for pressing oil from hemp plants in front of the White House while locked in a steel cage. And, as my former Mother Jones colleague Josh Harkinson chronicled after spending a wild evening drinking beers and smoking spliffs with Bronner back in 2014, the exec grew his own fair-trade, organic palm oil and coconut oil overseas when he couldn’t source it elsewhere.

In 2019 alone, it donated nearly $7 million—about 5 percent of its revenue—to a variety of charitable causes. But of all causes last year, Dr. Bronner’s gave the biggest bit of change—more than $3 million—to drug policy reform. In the past, Dr. Bronner’s drug-related activism largely centered on cannabis legalization, but now the company is turning its energy to a radical, new frontier: psychedelics.

That was our focus when we met up last fall, back when it was, needless to say, a simpler time. News of the novel coronavirus—and the corresponding wild demand for hygienic products—wouldn’t come until months later. Today, the soap company has seen demand for its products spike, but at the same time it’s kept a keen focus on supplying soap and sanitizers to front-line workers and at-risk communities. “It’s been nuts,” Bronner told me over the phone last month. Production has been “dialed up to 11,” he said, and during the past couple of months, the company simply hasn’t been able to meet all its orders. Still, as of mid-May, it had donated more than 25,000 units of hand sanitizer and soap to those in need; it had also given $20,000 to the San Diego COVID-19 Community Response Fund and $50,000 to California’s Immigrant Resilience Fund, which is helping to support the 2 million undocumented Californians who are not eligible for federal stimulus money. (Dr. Bronner’s also announced this week that it’s donating $25,000 to “organizations, both in Minnesota and nationally, that are working to end anti-Black racism and abuse.”)

Even without the increase in coronavirus-related demand, Dr. Bronner’s “constructive capitalism” model has seemed to work for its bottom line: The company has grown every year since at least 2010, and in 2019, brought in $129 million in sales—a 60 percent jump from what it sold five years earlier.

“We definitely get told, angrily, to just stick to making soap by whoever doesn’t like the position we’re taking on a given issue,” Bronner said. “But I would say overall, even people who disagree with us respect that we’re out there standing up for our beliefs.”

As Bronner likes to say, “Whatever your subculture is, we’re your soap.”

Dr. Bronner’s

As we drove across town in his rented Kia Soul to the People’s Cafe, a vegan coffee shop, Bronner told me, “I totally believe that we have a right to use psychedelics responsibly in our own home, out in nature.” He pointed out that research shows psilocybin, a psychedelic chemical found in hallucinogenic mushrooms, can have healing properties, especially for people struggling with mental health conditions like addiction and anxiety. As he wrote in a September blog post on the company’s website, “We firmly believe that the integration of psilocybin therapy…is crucial to healing epidemic rates of depression, anxiety, and addiction.” (In 2018 and again in 2019, the Food and Drug Administration granted “breakthrough” status to psilocybin for treating depression and major depressive disorder, a designation based on promising clinical evidence that allows companies to expedite a drug’s development. Some of the most advanced findings have been with cancer patients, where research shows psilocybin can decrease depression and anxiety.)

Just before we met last year, Bronner and Hardwick had flown in from Portland, Oregon, where they had attended the official launch of an effort to essentially legalize magic mushrooms for these purposes. “IP 34” is a state ballot initiative Oregon voters will likely consider in November that would legalize psilocybin for therapeutic uses in restricted settings—a possible “model for the rest of the country,” according to Bronner. Dr. Bronner’s, he had announced the day before, would donate $150,000 to the initiative. Last year, the company had financially supported the passage of Initiated Ordinance 301 in Denver, Colorado, which made history when it became the first city to decriminalize psilocybin. (Oakland, California, became the second major city to do the same last summer.)

But like all things, the coronavirus threw a wrench into big plans for 2020. While Oregon had most of its signatures to move the initiative forward before the pandemic hit, Bronner announced last month that the company would be giving an additional $1 million to the campaign supporting IP 34. “We’re stepping up bigger than we expected in Oregon, just because it’s a difficult fundraising landscape right now,” Bronner told me. It’s likely IP 34 will reach a goal of 145,000 signatures before the July 2 deadline—“one way or the other, we’re gonna make it happen,” Bronner said. Still, the company had planned to sponsor an Oregon-based conference on psilocybin therapy which was canceled because of COVID-19. The coronavirus also effectively ended a similar initiative in California—“they didn’t have enough signatures when COVID hit to finish the deal,” Bronner said.

As we walked up to the restaurant, I asked Bronner about his own psychedelic experiences, which he has been open about in the past. He told me that his first encounter was with mushrooms, in a friend’s room while he was studying biology at Harvard. “I remember looking down on my arm, and whoa”—he recalled thinking—”what does it mean that I’m in quantum continuum with my environment? At a quantum level, there’s not a difference between me and the world. And when I eat and I poop, the world is pouring through me.” He believes that in addition to helping people suffering from mental illness, this feeling of connectedness with the world brought on by psychedelics may help people be better stewards of the planet. Bronner said the response to his company’s push for psilocybin therapy has been “very positive,” at least on social media.

Bill O’Leary/The Washington Post/Getty

While the Oregon psilocybin initiative is what Bronner said—between bites of a vegan chicken quinoa burrito and a vegan omelet he split with Hardwick—he was “most excited about” for 2020, he was still focused on the broader mission of fair cannabis policy. States including Montana, South Dakota, and Arizona could see recreational, adult-use pot on the ballot in November, meaning these will be the key “battleground” states for Dr. Bronner’s. (Efforts in Oklahoma, Missouri, and Ohio have stalled out due to COVID, organizers say.) In all, the company plans to spend “north of” $2 million in 2020 on drug policy reform, split between support for legalizing cannabis, approving psilocybin therapy, and replacing jail time with addiction treatment. (Ballot initiatives on jail diversion are in the works in Oregon and Washington, though it’s unclear if these initiatives will have enough signatures to qualify.) Dr. Bronner’s support will translate to donations, but also social and marketing resources, maybe even some limited-edition soap bottles. Dr. Bronner’s has in the past printed labels to build support for issues including GMO labeling, minimum wage, and regenerative organic agriculture. It’s currently prepping a special bottle dedicated to “integrating psychedelic therapy” to launch in September, according to Bronner.

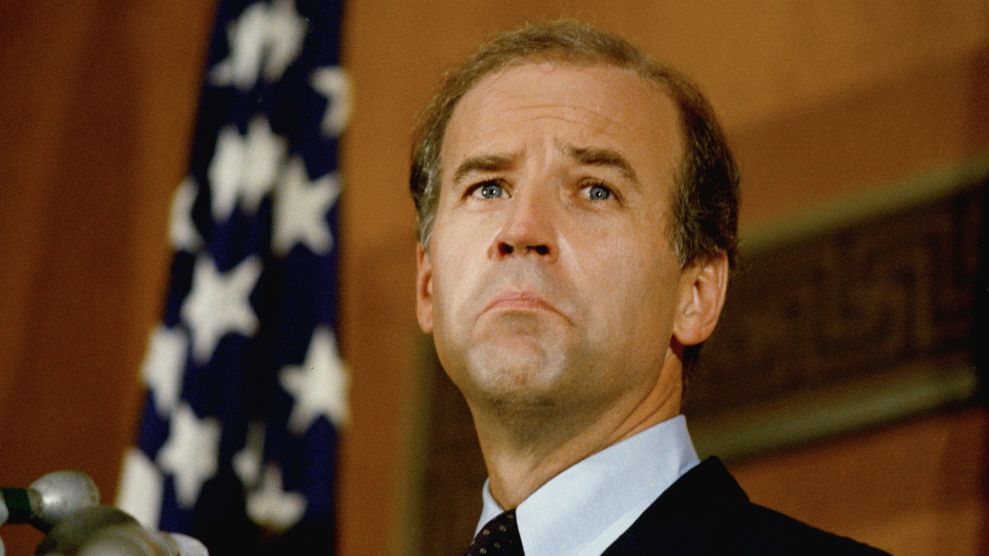

It’s almost like, maybe this company is too good. Initially, I wondered if Dr. Bronner’s was practicing some kind of dark magic; how could an activist company, an unapologetic one at that, also be so profitable? Oh, and did I mention Dr. Bronner’s caps executives’ salaries at five times that of the lowest-paid employee? I’m pretty much a glass-half-full kind of person, but still, I wanted to find something to latch on to, be skeptical of, poke holes in, or, at the very least, find ridiculous. While maybe there was just a little bit of the latter, what I saw really was a refreshing kind of corporate existence in an era when a self-serving business executive is literally running the country. “It’s definitely a more sucky environment,” Bronner says of working for reform under Trump, “but [George H.W.] Bush sucked, you know? It’s not new. You just kind of keep working—even under Obama, there was plenty of shitty things. You just gotta do what you can.”

Toward the end of lunch, I asked Bronner which of the then-plentiful Democratic presidential candidates he liked. He said he didn’t have a favorite and hadn’t “really been following” the campaigns, but said he supported senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, though he really liked Sen. Cory Booker. Finishing off a cardamom chai tea with oat milk, Bronner said Booker, who has backed legislation to legalize cannabis nationwide, is “super dope.” Getting at least one prediction right about 2020, he added, “I mean, he doesn’t have much of a chance, but he’s awesome.”

“I want to give him 420 bucks,” Bronner said to Hardwick. “Remind me we’re going to give him 420 bucks.” (I checked back later; he did.)