A new residential development in Austin, Texas.RoschetzkyIstockPhoto/Getty

This story was originally published by the Center for Public Integrity.

AUSTIN, Texas—Real estate developer Jim Young moved to Austin more than 20 years ago and has watched the gentrification of its east side. Once home to mostly low-income Hispanic and African American families, the area now caters to millennials and young professionals with craft breweries, coffee houses and food trucks offering tacos, lobster and vegan fare.

As Young embarked on his biggest project to date, a 360-unit apartment complex in the center of East Austin, he learned that the property was in a so-called opportunity zone, one of 21 low-income areas in the Austin area eligible for tax-free investments aimed at attracting businesses and affordable housing. It became apparent to Young that the new federal incentive, enshrined in the 2017 tax law that created thousands of opportunity zones nationwide, would likely lead to the type of development that squeezes out low-income residents, as big investors pour more cash into an already-thriving area.

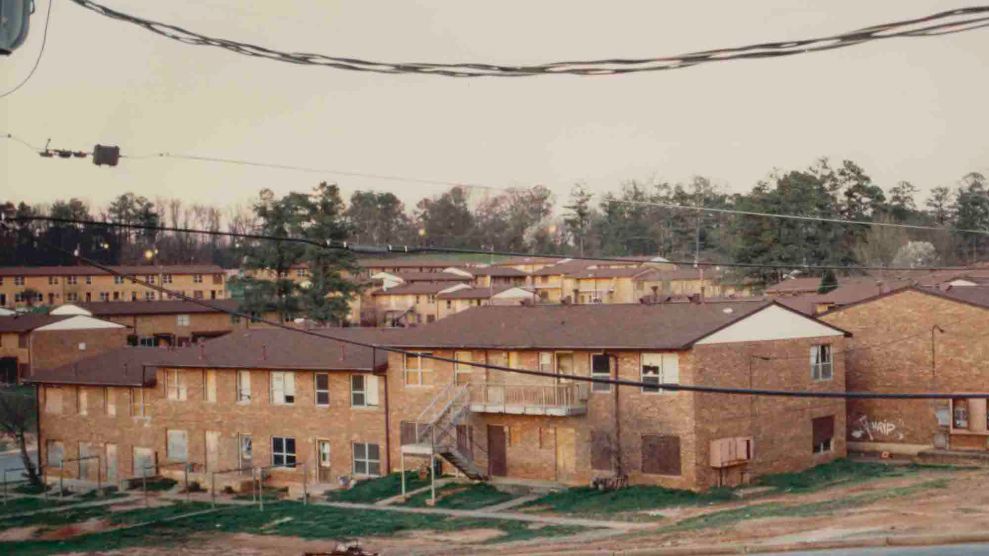

To make way for his new complex, Young planned to raze a 51-year-old apartment building where low-income families lived. But he realized that might add to the ongoing displacement of East Austin families. Instead, the West Point grad and former tank commander has started on a multi-year personal crusade to find temporary homes for the low-income families living there and arrange for them to return if possible.

“You realize,” he says, “that there is an opportunity to do more than just make money.”

But wealthy investors, relying on the generous opportunity-zone tax breaks, don’t all share Young’s sentiment. Months before the novel coronavirus swept into Americans’ lives, hot real estate markets such as Austin had been the target of a big influx of cash from investors seeking to take advantage of the tax benefits allowed under the 2017 tax law signed by President Donald Trump. Nestled within the sweeping law is a provision that gave wealthy investors tax incentives, including profits free of any taxes, to put money into real estate projects and new businesses in needy neighborhoods.

By the end of March, at least $10 billion had been invested nationwide in opportunity zone funds—pools of money from investors looking to tap into the tax break—that primarily sunk the funds into residential and multifamily projects, according to accounting firm Novogradac. On Austin’s east side, investments in neighborhoods in opportunity zones reached $825 million in value last year, four times higher than in 2017, according to Real Capital Analytics, which tracts real estate investment.

Affordable housing advocates expressed hope early on that the opportunity-zone program would benefit low-income renters, encouraging the development of affordable housing. The United States has a shortage of more than 7 million homes for low-income people, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. The coronavirus has made the housing crisis worse, with more than 13 million low-wage renters now struggling to pay their rent after losing jobs or a part of their income, the coalition estimates.

But for the most part, affordable housing hasn’t been on investors’ project lists. High-end apartments, hotels and office buildings are. Even now, as commercial real estate is facing a reset as businesses rethink office culture and many employees work remotely, investments in tax-friendly opportunity zones are continuing, albeit cautiously, in apartments built at market rates, not for low-income individuals.

Trump and members in Congress are now touting opportunity zones as a way to boost economies in those same low-income communities hit by the coronavirus. In an attempt to show his support for minority communities hard hit by the COVID-19 and the protests over George Floyd’s death, , Trump bragged that opportunity zones have “created tens of thousands of jobs” in low-income, mostly minority, neighborhoods.

There is no evidence that opportunity zones are benefiting low-income residents living in these neighborhoods. Developers and investors are not required to publicly report what they are investing in or if it creates affordable housing, jobs, or higher wages for the residents who live there. A recent study by the Urban Institute found that opportunity zones should be “redesigned so government dollars are allocated effectively and help” achieve intended outcomes like improved quality of life for low-income people.

Despite that, the Trump administration is touting the tax-free investment vehicle as a way to “lift Americans out of poverty and bring economic and community revitalization to the areas that need it most, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.” A bill in the House would expand opportunity zones to allow tax-free investments in small businesses impacted by the coronavirus.

Cities where development was dynamic before the pandemic hit, such as Austin, are expected to bounce back quicker than others, once the novel coronavirus is in the rearview mirror. But critics argue those cities don’t need the tax incentive to attract capital. The program will continue to give tax breaks to the wealthy while not helping low-income and primarily minority neighborhoods.

Projects like the one just a few miles down the road from where Young plans to build his apartment complex. There on a side road off of Bastrop Highway stands a 342-unit complex called East Vue Ranch. As it was nearing completion last summer, global investor Starwood Capital Group bought the development as part of what it calls its “growing Opportunity Zone portfolio.” The complex boasts a pool courtyard with “multiple tanning ledges,” an arcade gaming room, a coffee bar and a dog-wash station. Rents have topped out at nearly $2,600 a month—about $2,000 more than what would be considered affordable for the city’s low-income residents in the east side neighborhood.

Kathryn Kranhold/Center for Public Integrity

East Vue Ranch, critics argue, is just one example of how investors are taking advantage of the tax law’s freewheeling guidelines. In 2018 and 2019, at congressional hearings and events when opportunity zones were just beginning to form, politicians promised the law would bring jobs and affordable housing to low-income neighborhoods. “Our goal is to ensure that America’s great new prosperity is broadly shared by all of our citizens,” Trump said at a December 2018 White House event lauding opportunity zones.

But that’s not how the Trump administration structured the program. In guidelines released at the end of last year, the Internal Revenue Service rejected recommendations from national affordable housing advocates and cities including Austin that would have required investors and developers to show how their projects benefited communities before they could qualify for the tax break.

The IRS said the recommendations “would present numerous obstacles” for investors “and ultimately reduce, rather than increase, the total amount of investment in low-income communities.”

The ruling confirmed critics’ worries that the program won’t help low-income residents of opportunity zones, the very people it was supposed to.

Christine Maguire, Austin’s redevelopment manager, said cities have no input into opportunity zone investments. Opportunity zones are “for investors who are sheltering” financial gains from taxes in exchange for these investments, she said, and investors have no requirement to work with cities to identify and invest in projects that would benefit neighborhoods.

Doing the walk

Driving through East Austin in his gray Ford Focus, the 48-year-old Young pointed out the area’s transformation. He gestures to an empty lot that has been turned into a courtyard of food trucks offering Indian tacos, barbeque and Puerto Rican fare. Young said, the food court is temporary. “Future development,” he noted.

Young pulls off Springdale Road, one of the main arteries in East Austin. The busy thoroughfare cuts through a slice of old and new, churches being converted to condos, lots storing rusty nitrogen tanks, and community gardens. He gives a tour of an old warehouse that is now an indoor rock-climbing gym; it’s middle of the day, and athletes of all ages are climbing the colorful synthetic rock formations. Adjoining the building is a craft brewery, Austin Eastciders, which took over an empty railroad station.

Around the corner from the rock climbing and brewery is Calle Limon, named after the Limon family, which owns several homes there. Chickens scurry across the short road in front of newly built condominiums. The two-unit narrow complexes are squeezed onto lots originally laid out for single-family homes. The condominiums recently appraised for nearly $900,000 each, two to three times more than the adjacent 1940-era homes. Developers have leveled cottages down the street and plan to build a row of similar complexes. Over the last five years, land values throughout the area have doubled or even tripled, forcing many longtime residents and their heirs to sell because of rising property taxes.

Young moved to Austin from Fort Hood, Texas, after he left the Army in 1998. In 2001, he started his home-building business in East Austin because it was a few miles from the core of Texas’s capital city, home to the state’s flagship university and the South by Southwest music festival. Gentrification was a concern back then, but Young could still afford to buy the empty lots.

Digging through his computer files, Young digs out old photos of his first projects, single-family homes with small efficiency apartments, or “granny flats.” Back then, he advertised his rentals with handmade fliers highlighting energy-efficient appliances in a “Two Bedroom Beauty,” for example, and noting that “means very LOW utility bills for you.”

But development costs have soared since. That’s why Young is trying to figure out how to build his market-rate apartment complex while ensuring he doesn’t displace dozens of low-income families. He said in the coming months that he will seek opportunity-zone funding for the next phase of his development. Meanwhile, Young is adhering to one of the program’s implicit goals: asking for the community’s input and providing affordable housing to existing residents who could be displaced.

Before seeking Austin’s planning commission’s approval for his project, the stocky Texan took his proposal to a neighborhood watchdog group that goes by the name East MLK Combined Neighborhood Plan Contact Team. The group, which takes its name from East Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in the area, is a city-sanctioned organization that monitors development and whose support Young wanted so he could secure the zoning changes he needed to build the larger complex.

At a meeting in the spring of 2019, Young told the group he planned to tear down a 68-unit apartment complex on Goodwin Avenue to build the bigger one. The tenants would have to leave, Young said, but he would help them find housing and pay for moving expenses.

Without any pressure from Austin officials or neighborhood advocates, Young promised residents they would have the “right to return,” a concept housing advocates nationwide say reduces displacement. After closing on the Goodwin Avenue building in October, Young changed tenants’ leases to give them first dibs on the new apartments.

One of the residents, Tony Hill, a 53-year-old Army veteran, said he appreciated the early heads-up from Young that he will eventually have to move. He pays $875 a month for his one-bedroom apartment at the Goodwin complex and signed another one-year lease. Hill is resigned to finding a new home eventually. “I was a soldier. Moving around has been a thing in my life,” he said. “I’m glad I got the word early.”

To secure the zoning change, Young committed to provide more than 30 rent-restricted units to low-income families below 60 percent of the Austin metro area’s median family income, which is currently set by federal housing authorities at $97,600. If renting today, a family of four would need to make less than $58,560 a year to be eligible.

As part of the deal with the city, Young is allowed to build more market-rate units on the lot than previously permitted.

Young’s approach was refreshing, neighborhood residents said. He held a meeting at the aging apartment complex with tenants in late July. Prior to the meeting, in the humid heat of July 4, he and his 6-year-old daughter, Morgan, walked around the complex handing out fliers in English and Spanish and gave out business cards.

“He doesn’t just talk; he does the walk. He gets his hands dirty,” said Angela Benavides Garza, the onetime chair of the neighborhood contact team, which supports the project.

Young’s approach was so welcomed that last summer the neighborhood group created a new set of developer guidelines based in part on Young’s proposal. To get the group’s support, developers need to agree to protections for existing tenants including the right to return to the new building and providing moving assistance.

“Plenty of folks in Austin don’t want to see the city change,” said Jon Hagar, an architect who leads the East MLK team. “Change is going to happen, but we need to make sure the existing residents have the opportunity to benefit from it.”

Young isn’t completely driven by socially minded development. He is ambitious and recently announced an apartment project in the high-end historic Pearl District of his hometown of San Antonio. He said he wants to make the highest return possible for his investors but is sensitive to the impact development can have in low-income neighborhoods. He said he has “more perspective” since he knocked down his first “junker house.”

“Someone would say, ‘You just sent the property taxes skyrocketing,’” Young recalled.

Now, he said, “I have more perspective to understand and try to mitigate those things.”

“I am a developer, and I’m trying to make money for people,” he said. “You can do that and still take care of people, do things to make life smoother and change the way people transition.”

When asked how developers and politicians can preserve a neighborhood’s character, Young struggled to answer. “If we don’t build responsibly but densely in our urban core, then we’re going to have sprawl,” Young said. It’s important to “include the community that’s there” when developing projects, he added.

Investing in luxury

East Vue Ranch sits just southeast of Young’s project. Last summer, it was bought by Starwood Capital Group, which holds more than $60 billion in assets worldwide, including hotels, apartment complexes and shopping malls. In a press release last year, Starwood described the acquisition of the high-end complex as “representative of its growth-focused investments that it would be targeting across opportunity zones.”

But for many East Austin housing advocates and residents, the development is symbolic of the ongoing displacement and gentrification of the city’s low-income and historically minority neighborhoods.

Kathryn Kranhold/Center for Public Integrity

It all started in 2015, before opportunity zones were on the map. One of Austin’s most well-known developers, Oden Hughes LLC, proposed to build a 356-unit high-end apartment and retail complex on a 23-acre parcel that included the Cactus Rose Mobile Home Park. Oden Hughes planned to evict the more than 50 families—in excess of 200 adults and children—who lived there.

The mobile home community was in Montopolis, one of the city’s eastside neighborhoods historically segregated by Austin’s 1928 master plan, drawn up to rezone the entire city mostly along racial lines. Over the past 20 years, the area has been gentrifying, bringing in new businesses and pricey condominium and apartment developments, which has helped push out Hispanic and African American families.

Austin neighborhood advocates argued Oden Hughes’ proposed project would exacerbate gentrification. “It is the displacement of the most vulnerable population in East Austin,” Susana Almanza, head of Montopolis Neighborhood Plan Contact Team, wrote to the city’s planning commission in 2016. The team is another one of the city-sanctioned neighborhood groups.

In its presentation to the commission at Austin City Hall, the developer’s lawyer offered to give $1,000 to each family to relocate their mobile home. At the meeting, Cactus Rose residents crowded into the hearing room and waited their turn to approach the microphone. Saul Madero was among those who spoke. He wore a red T-shirt emblazoned with the name of his employer, Joe’s Bakery, a venerable establishment that regularly hosts “get out the vote” days. Through an interpreter, Madero asked for “compassion and understanding.”

He told the planning board members: “We’re a low-income community. But the only fortune that we’ve had is our home, our family, and the Number Four bus,” which the residents’ children rode to schools and the nearest library.

The commission deferred a decision on the zoning request, leaving it to the city council.

Oden Hughes and neighborhood activists continued to battle over the project until the company agreed to pay $10,000 to each Cactus Rose family who owned a single-wide mobile home—10 times its original offer. At a public hearing announcing the deal in November 2016, resident Cynthia Martinez thanked Almanza and Oden Hughes for reaching a resolution, including allocating money that would allow the families to purchase new mobile homes.

It wasn’t a happy ending for everyone. Madero said the fight with the developers drove a wedge between him and his wife. He said they disagreed over his involvement in the negotiations, and she didn’t understand why he needed to take a leading role. They eventually separated.

“When there’s that type of stress, one of two things can happen,” Madero said in Spanish, speaking through an interpreter. “It makes you stronger and unites you as a family, or it breaks you. In my case, there was no unity with my family.”

Madero sold his mobile home in Cactus Rose. He now lives in a recreational vehicle he bought from a former neighbor. He works two jobs as a waiter—one at Joe’s Bakery and another at a Chuy’s, a Tex-Mex restaurant chain. His estranged wife and three of his children are living together in an apartment.

“I lost everything, but I’ve decided to leave all of that behind and start again from zero,” Madero said, in an interview earlier this year.

After the area was named an opportunity zone in 2018, more investors came and commitments to the community were broken. While seeking to get approval for the zoning change to build the apartments, Oden Hughes told city officials that units would rent for between $850 and $1,800 a month—30 to 60 percent lower than average rents in the area, the developer boasted.

But Oden Hughes’ promises of modest rents on the former Cactus Rose site vanished last year after Starwood Capital Group bought the apartment development through its opportunity zone fund and renamed it East Vue Ranch.

To market its new property, Starwood borrowed familiar Austin taglines such as “South by” and “City Limits” to name the units’ floorplans. The rents started at more than $1,200—more than 40 percent higher than what Oden Hughes had proposed at the low end. Pricing for two-bedroom have ranged over the months, asking as much as $2,400, more than 80 percent higher than the median rent for the area, according to Census Bureau data. Nearly 60 percent of residents in the area have trouble paying the area’s median rent of $991 a month, according to census data.

A Starwood spokesman declined to comment.

The value of the Oden-Hughes-Starwood deal was not disclosed. In 2017, when Oden-Hughes bought the property where the mobile homes were, it was valued at almost $1 million. Before Starwood bought the partially-build apartment complex last year, the property assessed for about $5.5 million. The latest assessment of the apartment complex: $21.9 million.

The investment community and developers enthusiastically pushing opportunity zones are harshly realistic about the tax program’s intent and impacts on low-income people.

“Opportunity zone investors, even those who are incredibly mission driven, cannot control displacement,” Margaret Anadu, head of the Urban Investment Group at Goldman Sachs, said at a conference in Washington, D.C., last summer.

At the time, Goldman Sachs, which manages eight opportunity zone funds, had made 13 opportunity zone investments totaling nearly $400 million. The firm said it had invested in affordable housing in New York City, Baltimore and Salt Lake City, which includes units for low-income residents. Goldman Sachs declined to provide details.

Anadu said in an interview, however, that private investment typically does not build affordable housing by itself; government needs to get involved. “I think it is most successful when the private sector can work in concert with the public sector,” she said.

Austin developer Warren Walters has been part of the boom and bust cycles of real estate from Washington, D.C., to Texas. He has participated in other tax-incentivized real estate developments over the years, including ones that offered tax breaks for building apartment complexes. He acknowledged that certain opportunity zone-funded projects give the tax program a “blackeye,” and are “boondoggles for the rich.” But he defends the opportunity zone tax break program, saying projects in certain neighborhoods would not have happened without the tax incentive.

One of Walters’ projects is a multifamily housing complex in Manor, a town that sits on the outskirts northeast of Austin and is best known as one of the film locations for “What’s Eating Gilbert Grape?” Warren refers to the project informally as so-called “workforce” rental housing, which typically rents to individuals and families earning from 80 percent to 120 percent of the area’s median income. For Austin, that’s between $75,693 and $113,430. Walters said his complex will eventually provide needed homes to individuals such as teachers and government workers who cannot afford Austin’s high rents. Opportunity zone incentives have “been an accelerant” for projects like Manor, said Walters, who has raised money from investors for his projects

“It’s brought good things sooner than they would have ever been there,” Walters said.

Wanted: Responsible investment

Austin needs all types of housing. Until COVID-19 swept through the country, the metro area had the nation’s third fastest growth rate over the last decade, growing 30 percent since 2010 to 2.23 million in 2019. Apple Inc., Google and Oracle Corp. are expanding their footprints in the city. Tesla’s Elon Musk is considering opening a factory in Austin to build its electric truck.

While the coronavirus is expected to slow population growth in Austin by as much as 15 percent this year, eventually people will start moving to the city again, said Angelos Angelou, the former chief economist for Austin’s Chamber of Commerce and now a consultant.

“As soon as this coronavirus appears to be behind us, we’re going to see a large influx of people coming to Austin and other cities in Texas,” he said. And that means investments in opportunity zones in places like East Austin will heat up again, renewing displacement concerns in gentrifying neighborhoods.

Meanwhile, the city is clinging to its slogan, “Keep Austin Weird.” For more than two years, council members have debated how to advance a contentious zoning overhaul that seeks to accommodate the city’s growth, its historically diverse culture and protect individual property rights.

The reality is that Austin’s shortage of housing for low-income residents is worse than larger cities such as Los Angeles, Dallas, and Houston. For every 100 people earning less than 30 percent of the Austin metro area’s 2018 median family income of $94,617, Austin has only 14 affordable units available. Only Las Vegas has a more severe shortage, according to the nonprofit National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Kathryn Kranhold/Center for Public Integrity

Austin lost 71,100 affordable rental units over the last 10 years. Affordable apartments now make up only 15 percent of the city’s total available rentals, down from 48 percent in 2008, according to a recent study by the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. The state of Texas experienced the biggest decline nationwide of units renting for less than $800 a month, while the number of rentals priced at over $1,000 a month nearly doubled.

Local officials and housing advocates were hopeful the 2017 federal tax law would encourage the building of affordable housing and projects such as fresh-food grocery stores. The law allowed governors to nominate eligible census tracts that had high poverty rates for opportunity-zone designation, which the Treasury Department had to approve.

While many cities lobbied to get as many opportunity zones as possible, wary Austin officials nominated only four tracts out of dozens that were eligible. Hoping to target the investments in those tracts, they told Republican Gov. Greg Abbott the neighborhoods were the city’s neediest.

Abbott nominated the four tracts but added another 17—the majority of which were in East Austin. All of the tracts were approved.

Concerned about the types of development these areas might attract, the 10-member city council passed a resolution in October 2018[1] calling for “responsible investment” that improves residents’ quality of life.

Councilwoman Delia Garza, whose district includes the four tracts in which Austin officials wanted to focus investment, met in the spring of 2019 with partners of a new fund called Blueprint Local, which invests in opportunity zones. Blueprint’s founder, developer Ross Baird, made a pitch on the blogpost website Medium, saying the fund was looking to “help entrepreneurs build wealth and transform street corners, neighborhoods and communities across the country.” In Texas, Baird partnered with basketball legend David Robinson, who played for the San Antonio Spurs, and his son, David Jr., who is working for Blueprint as an associate.

In meetings with Garza and her policy advisor, Cynthia Van Maanen, Robinson Jr. and Blueprint’s local partner, Jonathan Levy, said they were looking to invest in areas designated as opportunity zones and “wanted to do it in a socially responsible way,” Garza recalled in an interview at her city hall office.

Garza urged Levy and Robinson Jr. to consider opening a grocery store in an opportunity zone in one of the four tracts on the far east side, where there is vacant, low-cost land.

She hasn’t heard from them since.

Through a spokesman, Levy declined to comment. In an email, Robinson Jr. declined to comment on behalf of himself and his father. Blueprint’s Baird didn’t reply to requests for comment. In an interview with CNBC in November 2019, the senior Robinson said he was helping raise $50 million for Blueprint to invest in opportunity zones, highlighting potential projects such as grocery stores in “food deserts.”

More luxury apartments

But that hasn’t happened in Austin despite the requests. In August 2019, Blueprint announced a partnership with Oden Hughes to build another luxury apartment complex in an East Austin opportunity zone—this one with 279 units, two resort-style pools and a skyline terrace.

For this project, Oden Hughes agreed to set aside 28 units for families earning 80 percent of the city’s median income in exchange for changing the zoning from commercial to mixed use. The developer plans to charge market-rate rents for the remainder of the units. Rents for those 251 apartments will start at $1,560, twice as much as the median rent in the East Austin census tract and far out of reach for people living in the neighborhood.

An influential neighborhood planning organization called the Govalle/Johnston Terrace Neighborhood Plan Contact Team agreed to support the project after Oden also committed to contributing $250,000 to the East Austin Conservancy, which helps pay property taxes for residents whose taxes have escalated because of gentrification and cannot afford to stay in their homes otherwise.

In an interview, the group’s chair, Austin artist Daniel Llanes, said Oden Hughes appeared to have learned from its encounter with the Cactus Rose Mobile Home Park and looked to find solutions for the neighborhood without contentious negotiations.

“We’re not interested in a fight with people,” Llanes said. “Growth happens, change happens. What’s important is that it’s integrated change not exploitation.”

Steve Oden Jr., a co-founder of Oden Hughes, said in an emailed statement sent from his public relations consultant, the firm “engaged with the community, stakeholders and elected officials for a considerable time on both of our East Austin projects—and ultimately made meaningful changes to our proposals benefiting residents and the local community.”

Jake Wegmann, a University of Texas professor who co-authored a highly regarded study on East Austin’s gentrification, said the phenomenon is hard to stop. He supports, in general, building housing developments on unused commercial property because the demand for housing in Austin has soared. But Austin needs to change its policies to ensure a “healthy share” of this housing is within reach of people with roots in the neighborhood, he said.

After months of weighing whether to seek opportunity zone funds for his project, Jim Young is on board. He applauds the tax incentives because they may trigger long-term investment in housing and other infrastructure.

But if he receives funding from opportunity-zone investors, it won’t change his development approach, he said. After getting input from residents in the neighborhood, he’s working on other services he can offer low-income tenants living at his apartments, such as financial education classes.

“I want to build things that my grandkids can drive by and be proud of,” Young said.