Drew Angerer/Getty

When Pope Francis shocked Catholics last week by endorsing civil unions for same-sex couples, it didn’t take long for Aaron Bianco to hear about it. A Catholic professor of theology at the University of San Diego, he also happens to be openly gay and married. Several students immediately texted him when news of Francis’ comments reached the United States. “They were so happy,” he told me. “All they wanted to discuss” in class last week were the pope’s comments.

Bianco was happy too. But as someone who is painfully familiar with the vengeful homophobic wing of the Church, he knows that progress often comes at a price. Four years ago, he helped minister to the queer community at a parish in San Diego. When his work began attracting publicity, he became a target for right-wing Catholic agitators, who spent months sending hate mail and death threats. “Someone tried to burn the church doors down,” he said. “My husband eventually said, ‘This job is not worth it.'” Bianco finally quit despite support from his local bishop.

Queer Catholics in similar positions at parishes and schools would never have left their jobs were it not for the pressure. The Vatican may no longer speak as harshly of gay people as it did in 1986 when a Church document stated homosexual activity was indicative of a “disordered sexual inclination,” but civil unions and marriage have long been the third rail for even the more progressive bishops. Teachers at Catholic schools in Florida, Ohio, and Indiana have been fired for being in same-sex marriages. With backing from the Trump administration, Catholic dioceses all over the country have gone to court to defend the firings. In one instance, a Jesuit school in Indianapolis was forbidden from calling itself “Catholic” because administrators wouldn’t fire a gay teacher. Last year, the Trump’s Justice Department submitted a statement in court supporting the Indianapolis archbishop’s decision, saying it was permitted under the First Amendment.

Francis, who supported civil unions when he was archbishop of Buenos Aires, is sounding a more inclusive tone now as the Church’s leader. “Homosexual people have the right to be in a family. They are children of God,” he told an interviewer as part of a documentary film released in Rome last week. “You can’t kick someone out of a family, nor make their life miserable for this. What we have to have is a civil union law; that way they are legally covered.”

After the news broke, I reached out to Margie Winters, a service learning coordinator at a secular school outside of Philadelphia. She told me she felt “a lot of cautious optimism” after hearing about the pope’s remarks, adding, “The experience that I had in 2015, obviously, colors my experiences now.”

That was the year a school parent at Waldron Mercy Academy, a private Catholic school located in one of Philadelphia’s wealthiest suburbs, complained about her being married to a woman. Winters had worked at the school for nearly a decade and had long been open to the administration and faculty about her marriage. She just wasn’t out to the broader school community. “It was kind of the time of ‘don’t ask, ‘don’t tell,'” she says. Winters was called into a meeting with the principal and fired as the school’s director of religious education.

Despite outrage on her behalf from other teachers and parents—23,000 people signed a petition asking for her to be reinstated—Waldron leadership refused to reverse its decision, telling parents in a letter that “many of us accept life choices that contradict current Church teachings, but to continue as a Catholic school, Waldron Mercy must comply with those teachings.” Former Archbishop of Philadelphia Charles Chaput, who was replaced by Francis in January, even called the decision to fire Winters one that showed “character and common sense.”

Five years later, Winters says she was “really excited” to hear Francis’ endorsement of civil unions but frustrated that his comments seemed still to prioritize heterosexual marriages, while reducing her own to second-class status. “It’s wonderful that the rhetoric is becoming more positive, but I think it’s only a step,” she says. “It’s still an exclusion as well.”

Few Catholics are as familiar with the difficulty of getting the Church to liberalize its position on marriage equality as Sister Jeannine Gramick, the co-founder of New Ways Ministry, a pro-LGBTQ Catholic organization based outside of Washington, DC. She has spent decades ministering to gay Catholics, including Winters, despite a 1999 Vatican order prohibiting her and New Ways Ministry co-founder Robert Nugent, SDS, “from any pastoral work involving homosexual persons.” (“I came to understand through prayer and spiritual direction that I could not in good conscience follow their order,” she told me.)

Among the various implications of Francis’ remarks are that, even absent an actual policy shift, his words could lead school administrators to be more protective of LGBTQ staffers, Gramick said. “My experience is that most schools don’t want to fire their gay teachers, even if they’re married or in a civil union, but they’re afraid of the bishop,” she said. “Now, with the Pope’s statement about supporting civil unions, that will give the administrators more courage to not pressure those applicants who are LGBT to be silent.”

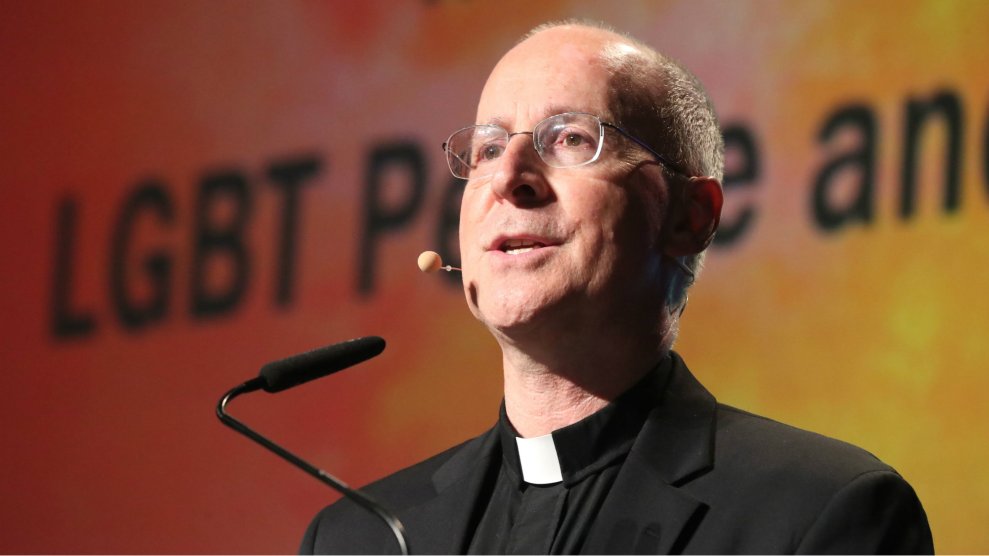

For any substantive change to follow this statement, more bishops will need to heed the pope’s example. That’s not such a sure thing in the United States, where “you have bishops who are violently opposed to same-sex civil unions,” said the Reverend James Martin, a Jesuit priest and author of Building a Bridge, describing the effort to create a “relationship of respect, compassion, and sensitivity” between the LGBTQ community and the church. “Some don’t seem moved by anything the pope says,” he told me.

One particularly conservative bishop, Thomas J. Tobin of Rhode Island, responded to Francis by announcing, “The Church cannot support the acceptance of objectively immoral relationships.” What Tobin failed to realize is the American church—if it’s defined by its people, not its leaders—already does widely support marriage equality. In 2004, only 38 percent of American Catholics supported gay marriage; by 2018, nearly 73 percent of them did.

Conservative Catholic leaders like Tobin no longer represent a majority, but they still enjoy outsize influence because the Trump administration continues to court their support. Four years ago, “Trump reached the presidency in large part because he won traditionally Democratic Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin, all states in which Catholics outnumber evangelicals by significant margins,” NPR reported on Monday. This time around, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo felt comfortable publicly blasting the Vatican in a naked appeal to anti-Francis Catholics last month. Trump, for his part, has been shameless in exploiting the partisan divide within the church. “Anti-Catholic bigotry has absolutely no place in the United States of America,” he said earlier this month. “It predominates in the Democratic Party.”

Bianco, the former parish administrator in San Diego, had certainly experienced bigotry, except it had been directed at him by an extremely vocal portion of right-wing Catholics. One website even accused him of overseeing a “homosexualist cabal” at the parish. Two years removed from that job, he reflected on one moment that stuck with him, a sign of good even in the midst of almost shocking levels of vitriol and hate.

It was October 7, 2017, the day Bianco’s parish held a mass to celebrate the 20th anniversary of a letter from American Catholic bishops that marked a welcome shift in its approach to gay and lesbian Catholics. Rather than demonize homosexual behavior, the letter affirmed God’s love for all people and urged Catholic parents to be accepting of their gay and lesbian children, even as it stopped short of any mention of same-sex marriage or civil unions. While notably addressed to parents and not LGBTQ Catholics themselves, the letter was still a milestone for queer Catholics. The anniversary of its publication brought some believers who hadn’t set foot in a church for years back in the pews. The event was denounced by Bianco’s critics, who assailed it online as a “pro-gay mass.”

After the service, Bianco remembers meeting an 82-year-old man. During their conversation, he told him that this had been his first time attending mass since he was 18. That’s when he came out as gay to a priest, who responded, “Don’t you ever come back into the Catholic church.”

“When he left, he was sobbing,” Bianco told me, “and he said to me, ‘Thank you for allowing me to come home.'”