From the moment Donald Trump descended the infamous escalator in 2015, he made clear his intention to terrorize immigrants. Four years later, the enduring images of his presidency were outdoor cages packed with migrant families and kids being ripped from their parents’ arms. Then came impeachment, and COVID, and an economic crash, and election season. Judging by cable news and front-page headlines, immigration had been largely forgotten.

But not by the Mauritanian electrician who was deported after 20 years in the United States to a country that still has slavery. Or the Indian coder afraid to unpack the boxes in his New York apartment for fear that he could be forced out at any moment. Or the Iraqi woman who stopped getting food stamps for her baby in order to preserve her husband’s shot at a green card.

Related stories

America’s Immigration System Was Already Broken. Trump Made a Weapon Out of Its Shards.Asylum Is Dead. The Myth of American Decency Died With It.An Explosive Government Report Exposed Family Separations and Other Immigration Horrors—in 1931Why a Second Trump Term Would Be Even Worse for Immigrants

The immigration system, already flawed and arbitrary before Trump, has become something much crueler, with repercussions far beyond the Mexican border.

Congress’ decades-long failure to pass immigration legislation has ceded virtually all decision-making to the president, and so immigrants find themselves at the mercy of whoever is in the White House. This administration has shown them none.

Here, we share the stories—in their own words—of eight would-be Americans who ran into Trump’s crackdown on legal and unauthorized immigration. In some cases, their futures hinge on what happens next Tuesday. For others, the results of the election are moot. It’s already too late.

As part of an effort to keep out working-class immigrants, the Trump administration issued a rule that blocks people from getting green cards if immigration officers decide they’re likely to use public benefits in the future—to become, in antiquated parlance, “public charges.” The rule has caused many immigrants to unenroll from public benefits. Shahad Sarmad stopped getting food stamps for herself and her baby because she fears accepting them will cause her husband, whom she is sponsoring for a green card, to be labeled a public charge.

Shahad Sarmad, 26

From: Iraq

Lives in: Austin, Texas

Shahad Sarmad as told to Noah Lanard

My husband and I are from Iraq. I’ve lost two of my family members since we applied for his green card in May: my father and my uncle, who was like a second father to me. He was an officer in the Iraqi military and was killed by ISIS. My father was in the army, too. He worked with the US military.

I couldn’t go back home for my uncle’s funeral because I’m the only person in my family who can work here. I work seven days a week. I went into a very bad depression after my uncle got killed. I left my full-time job and kept working as a delivery driver with Grubhub, which I need to do so that my husband won’t be considered a public charge. I barely make $1,200 a month.

My husband hasn’t been allowed to work since he moved here in December. He has a degree in biomedical engineering and used to work as a project manager in London. I got my degree in Iraq in business administration. Now I’m renewing Medicaid for my 18-month-old and me. My lawyer told me to stay on it but worries that it could make USCIS see my husband as a public charge.

After the first Gulf War, the economy in Iraq was very bad. My uncle and my father had to work for the Iraqi army so they could support their families. After 2003, they went back to serve in the army even though it was very dangerous. I felt scared my entire childhood. My father later worked in the US embassy in Baghdad and had lots of friends who were US officers. He started the process of applying to be a refugee in 2011. We thought it was going to take two years. It ended up taking seven.

I was 24 when I got here. I moved to the UK with my husband for a little while in 2018 but decided to come back to Austin when I was three months pregnant. I applied for my green card that year. I thought it would take six months. It ended up taking 17 months. I got it in February. While I was waiting, I went into a very bad depression. My husband wasn’t here, and I was living with my baby as a single mom. I wasn’t prepared for it. My husband returned on a tourist visa but is now able to stay while his green card application is being processed.

I heard about the public charge rule when I was still applying for my green card. I heard that if you’re using food stamps, you can’t bring your mother or your father to live with you. I stopped applying for food stamps immediately. I was desperate for cash to pay rent, but I didn’t apply for cash benefits. I will never do it. I will go work for 12 hours a day at a retail shop while eight months pregnant rather than receiving cash benefits.

I see people in social media groups saying you can receive unemployment if you’re sponsoring someone. Others say you can’t. And that makes us unsure. Should we do it or not? After I left my full-time job, my lawyer recommended that I keep working because of the public charge rule.

The government makes us feel like we’re not safe until we get our citizenship. I have a relative who got an $18,000 hospital bill. She went to the emergency room for kidney pain. She wasn’t on Medicaid because she was sponsoring her husband and didn’t want him to be considered a public charge. These stories are all around me.

I’m working and keeping myself busy, but it’s not fair to make my husband go nine months without working. He got a 30-day trial at a gym so he can get out for a while. He’s trying to study coding, but he still needs a Social Security number to go to community college. Everyone relied on him at his old job, and now he’s staying home all day with the baby or just doing his daily workout. It’s getting bad. Sometimes, he doesn’t eat or get out of bed.

He’s qualified to work for companies like Apple and Samsung. We saw all these Netflix episodes about people working illegally and getting caught by ICE. That was my nightmare when he applied for his green card. I was afraid of him getting rejected and then having ICE knock on the door. They’d deport him and he’d never be able to come back and live with us.

I think my husband will eventually get approved. I’m optimistic, even though he will have to answer questions about me getting Medicaid, me leaving my job, why he waited for a long time to apply for private health insurance. But I’m afraid it won’t happen until next year. I can’t keep going and working every single day. I go to sleep thinking, “Tomorrow I’ll take a day off,” but I can’t.

My mental health has really suffered these past few years. Sometimes I feel like I need to go to see a doctor just to talk about it. I’ve never said that to anybody. This is a lot of pressure for one person. I’m only 26, but with all the pressure in my life it feels like I’m 46. Dad had a heart attack then after that my uncle. I remember going back to work and crying while delivering pizza and sushi.

It makes me anxious to think about my husband’s application every day. It’s living with me. It’s eating with me. It’s drinking with me. Him getting approved is about being free again. People talk about light at the end of the tunnel. We’re still in the dark part of the tunnel.

We talked to eight people whose lives have been upended by the Trump administration’s immigration policies. You can read more about the project and find every story here.

Temporary H1-B visas are awarded to highly skilled foreign workers—most of them from India—after employers request to bring them to the United States. But in 2017, Trump made sweeping changes to the program, denying visas at a record rate. Some of the H1-B visa holders being denied, like 38-year-old Vishakh, have had visas for years and have degrees from US universities.

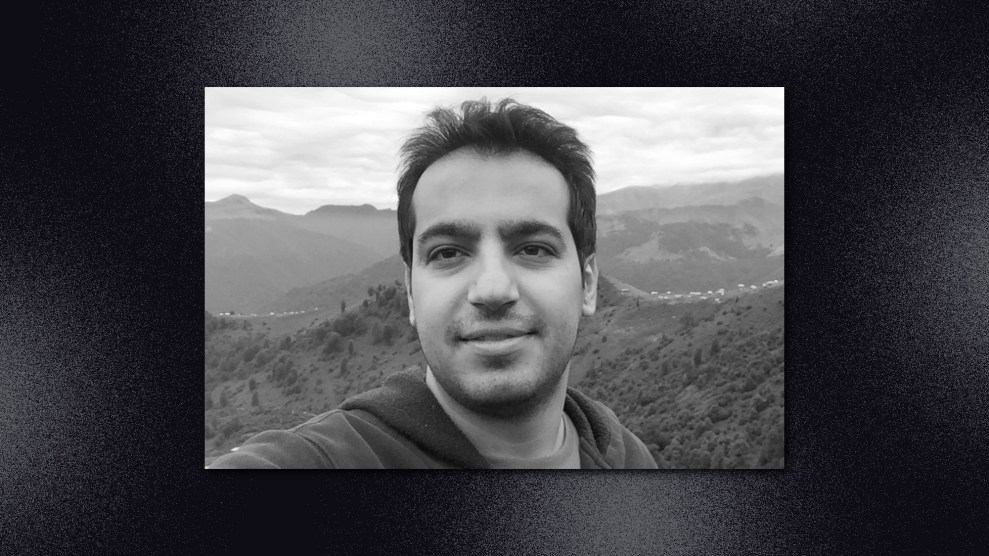

Vishakh, 38

From: India

Lives in: New York City

Vishakh as told to Fernanda Echavarri

I actually first came to the United States when I was a child. My mom was studying here, so I accompanied her when I was 8 or 9, and it left a huge impression on me because I was a curious person. The Indian educational system was pretty stifling. Here, you were allowed to have your own ideas and think for yourself.

I always wanted to go to school in the United States, and I eventually ended up in California with a student visa. Later on, I went to grad school at Columbia, where I did research in computational biology. The idea was always to have a career in research, but at some point, I decided to take a few years off and work in corporate America to pay back student loans. As an Indian citizen, I needed to be on an H1 visa in order to work here.

Once I started laying down some roots, had a social network, and got reasonably close to my colleagues, I started thinking about staying here for the long haul. So five years into the job—typically your H1 visa is good for up to six years—I approached my employers. They were happy to sponsor me for a green card. But that process is quite long. Back in the day, it used to be, on average, seven years for Indian and Chinese citizens. And eventually it became something ridiculous, like 10 or 11 years, and now, I think it’s at least 15 years.

I was approved for a green card, but there’s only a certain number of green cards that can be assigned to citizens of any country in any one year. If I had been, I don’t know, Norwegian, Nigerian, or whatever, I would have had my green card many years ago. So I was just renewing my H1 visa. But then, in 2017, I was trying to change employers and this transition, normally a very trivial process, really caused me a lot of heartache and trouble. What should have been two or three weeks of paperwork took more than two years.

Before, when you were switching jobs under an H1 visa, there was still a little bit of uncertainty involved, but it was sort of understandable. You still felt that the system was working. It was just a bit slow or maybe a little bit complicated, but fundamentally, the system was trying to obey something orderly, something rational.

People like me are used to the bureaucracy. But the cruelty that has happened in the last four years just feels so unnecessary, and I really fail to see who it is helping. The whole time that I was stuck in limbo, while I was waiting for my visa transfer to happen, it felt really, really hostile.

In August of last year, I was supposed to fly to San Francisco and give a talk, and it was a big deal. Two days before that, I got a letter in the mail saying my visa transfer was denied and that I must leave the country. So I call the lawyer and I’m like, “What’s the deal?” And she said, “You need to leave. Earlier, you could have stuck around for 60 days, maybe a bit longer than that. But now there’s a chance that they’d send you to ICE detention.” I told her I was committed to this talk, there were 200 people turning up— could I still go and fly back and then get rid of everything and I’ll leave the country? She said, “No, it’s a bad idea because you’re flying through the airports, and you never know.”

I have this degree, I have all this experience, I have all these accomplishments, but at the end of the day, what’s the difference between me and someone who doesn’t have all these opportunities in life? They’re coming here, they’re working hard, I’m sure they’re pulling longer hours than me, they’re living under the same kind of threat. There’s no such thing as a “good immigrant.”

The immigration system here has never been fantastic. I’m sure if you talk to different types of immigrants during the Obama years, you hear a lot of frustration. But what really changed was the system became unnecessarily cruel.

I believe in contributing to society. I natively speak English. I have an Ivy League degree. I’ve been contributing to the economy and have paid a lot in taxes. I don’t know what more I can do, right? And still they see it fit to give me a very short notice and just tell me to pack everything up and say goodbye. I said goodbye to everybody I know. I had final lunches with everybody. I said goodbye to my favorite places in New York City.

When I got the denial, my company was very supportive, and eventually we filed a lawsuit. Then the next day, magically, they reopened my application, and they approved it. But even to this day, if you come to my apartment, I still have a bunch of boxes packed with stuff. Why would I unpack fully? I unpacked some stuff because I have to cook and live and eat. But, psychologically, I can’t get myself to fully unpack to this day.

I like to bike to this place out on the Hudson. I sit there and look at Manhattan from a distance. I eat my empanadas and I just watch the river. So last year, I said goodbye to it. I did my final few bike rides and said goodbye. Now, it’s weird, almost a year has passed, and it feels bizarre to be sitting in the same spot. It’s almost like I’m not here.

We talked to eight people whose lives have been upended by the Trump administration’s immigration policies. You can read more about the project and find every story here.

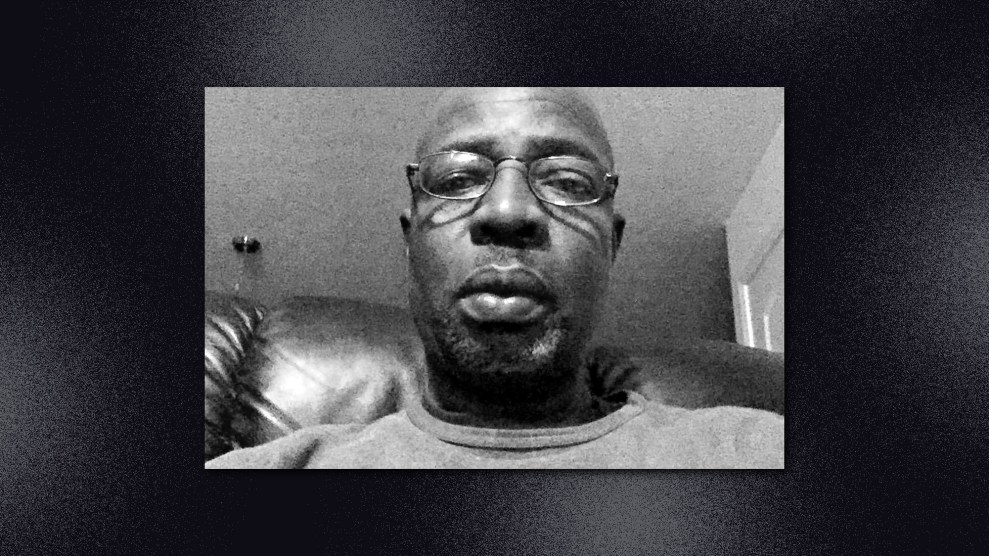

Three decades ago, the West African nation of Mauritania stripped many of its Black residents of citizenship. A large group of exiles formed a community in Ohio. The Obama administration allowed them to stay in the country even after they lost their immigration cases, so long as they checked in regularly with their local ICE office and followed the law.

Trump’s ICE upended that agreement and began arresting Mauritanians at their check-ins for deportation—even as the administration cut off trade benefits for Mauritania for failing to eliminate hereditary slavery. Goura Ndiaye was awaiting a hip replacement when ICE took him into custody. He is now suing ICE for medical neglect.

Goura Ndiaye, 61

From: Mauritania

Lives in: Dakar, Senegal

Goura Ndiaye as told to Noah Lanard

I was deported from Mauritania to Senegal in 1990. I came to New York in 2000. I was working in a store, and one day I saw a light wasn’t working. I said, “Do you need to fix this?” The guy at the store said, “You’re from Africa. You can do it?” I said, “Yeah, I was an electrician in Africa.”

After that, I moved to Columbus, Ohio. I lived in a motel and worked cleaning a restaurant. Then I told them I was an electrician and I fixed a light outside the restaurant. I didn’t know the system very well, but I’m an old electrician. Whatever they tell me, I can do it.

In 2009, ICE put me on supervision. I always went to my check-ins. I had my work authorization. I worked legally in the United States and paid my taxes. I started a family, built a house, and started my business as an electrician. I never committed any crimes.

On December 10, 2018, ICE called and asked if I was home. It was weird because they never called on the day of my check-ins. When I went to my check-in at the ICE office in downtown Columbus, they told me they were going to deport me to Mauritania. Then they took me into custody.

ICE put me in the Butler County jail, then after that Morrow County. They tried to deport me the first time on a commercial flight, but I refused, and they sent me back to jail. They said it doesn’t matter that you don’t want to go. We’re going to send all you guys back to Mauritania. We’re going to put you on a charter flight.

Before being detained, I had a health crisis. I have vascular necrosis and was supposed to have a total hip replacement. My doctor had scheduled me for surgery on January 4. On January 3, ICE took me to Louisiana to deport me on a charter flight. I told them, “I’m supposed to have surgery tomorrow. I cannot even walk.” Before the plane landed in Louisiana, I fainted because I hadn’t taken my blood pressure and pain medication. A guy came to take the shackles off. I couldn’t stand up anymore. They put me in a wheelchair and took me to see a nurse. We continued to Arizona, and I was granted a stay of my deportation.

That’s how I came back to the Morrow County jail. I kept going back and forth between Morrow County jail and Butler County jail with all this pain. Sometimes in Butler County, I would start crying because it was so painful. A correctional officer came to my room, and I was crying. They called the nurses, who didn’t even give me one pill. I saw many doctors. A specialist recommended surgery, but ICE never did anything for me.

They later brought me to a CoreCivic detention center. I was scheduled to see a doctor on a Monday. The night before, they came to get me. I thought they were going to deport me. I went to booking, and two ICE officers told me they knew I had a hip issue: “We’re going to try to take you somewhere to take care of you.” I said, “Really? Are you telling the truth?”

From there, they took me to Columbus airport. When I arrived, there were two officers waiting. One guy said, “You have to make it easy for me, because if you don’t, I’m going to use force.” I said to myself, “Oh, this is a deportation.” The plane went to Arizona. A guy there told me that I was going to be deported tomorrow. I tried to reach my lawyer, but she never answered.

I think the charter flight left on August 6, 2019. We arrived in Mauritania around August 8. We arrived shackled like criminals. The Mauritanian police held us at the airport for six hours before they released us. The next day, a friend helped me cross the river to join my daughter in Dakar, Senegal.

It’s difficult here. I’m not from here, for one. Second, I’m sick. Third, I’m not working. I’m living with my daughter and her family. They don’t always have enough money to help. I can’t eat what I want because I don’t have money. My life is a catastrophe. Even if I looked for a job, I wouldn’t get one anyway. You don’t have your health, you don’t have a job.

My first daughter in the US was born in 2004. The second is a boy who was born in 2013. The third is a boy who was born with Down syndrome in 2015. My girlfriend has to take care of him. My stepdaughter is supposed to go to college. Because of all this, she has to work part time to try to help take care of the bills. She’s the one helping me right now.

I speak to them almost every day. But it’s hard with the different time zones, and sometimes I have connection issues. It’s not easy for them. It’s not easy for me.

ICE always told me at the check-ins that I could stay in the United States as long as I didn’t commit any crimes. That was what the last government was telling us. That’s why I always went to check-ins early in the morning on my way to work. Sometimes, I’d come before the ICE office opened. I’d stand by the elevator. Then I’d go up, check in, and go to my job.

I almost collapsed on the floor the day they took me into custody. I was crying, to be honest, because I couldn’t believe it. The United States. The most powerful country in the world. Everybody fought to go to the United States because they said only the United States can help. That encouraged me to come to the United States. That’s why I couldn’t believe that day that they were going to deport me. I did nothing wrong. I love this country. Mauritania stripped me of my citizenship. Otherwise, I never would have gone to America.

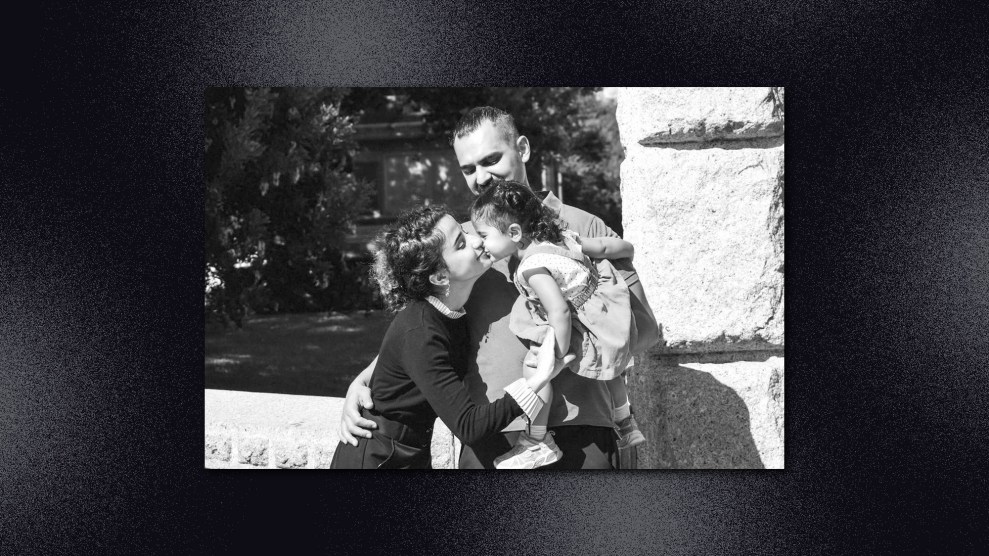

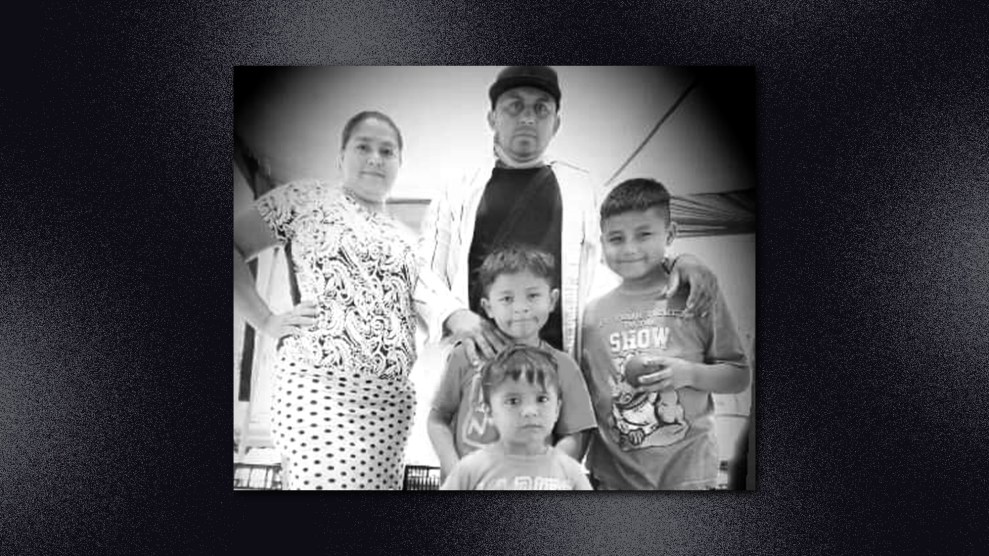

After fleeing extortion and threats in El Salvador in late 2018, Juan Carlos Perla, his wife, and their four young children waited in Tijuana for seven weeks before they were allowed to ask for asylum at the US border in early 2019. They then joined the now roughly 68,000 asylum seekers who have been sent back to Mexico as part of the Trump administration’s Migrant Protection Protocols program, which forces immigrants to wait on the other side of the border while their claims are pending in US immigration courts.

Juan Carlos Perla, 38

From: El Salvador

Lives in: Tijuana, Mexico

Juan Carlos Perla as told to Fernanda Echavarri

If I had known back then what I know now, more than a year and a half later, we wouldn’t have waited to present ourselves at the port of entry. We would’ve just tried to cross illegally. We thought we were doing the right thing.

Our three sons are now 8, 5, and 2 1/2 years old. My little one was 4 months old when we left El Salvador—and here we are in Tijuana still. My kids have missed out on school. My wife is very stressed and losing hope, but I keep telling her that it’ll be worth it. Being here this long hasn’t been easy—it’s been struggle after struggle and so many moments of anguish. We feel like we’re just navigating a sea of tribulations. But I guess God knows what he’s doing, so we’re still fighting.

Unfortunately, we got to the border after President Trump had changed the laws and officials were starting to send people to wait in Mexico after we legally asked for asylum at the ports. We were living in shelters and the streets, and the US officials kept telling us to come back to the port for the next court date. Last year, we went to court six times in San Diego. The way they mistreated our kids and the whole thing of going to court was such a sacrifice that at one point we thought we’d stay in Mexico. I had a work permit from the Mexican government, so I could work at a butcher shop. For a few months, we were able to rent a little place. We showed up with nothing, and the owner helped us while I tried to get some money to feed my family and my wife cleaned the house of the woman who let us stay there. I fixed up the place, but then when we had to go to court again, we came back to find that the woman had packed up our things and given them away, so we had nowhere to go. She treated us like invaders, and my kids are the ones who paid the consequences.

We had to go to a shelter where they mistreated migrants, especially children. Things were really bad there. From there we went to a third shelter, and I met a friend who let us move into an abandoned trailer. It was really old and full of ants, mosquitoes, and even rats. My middle son ended up covered in bug bites at one point. So we had to leave that too and are now living in another shelter for families.

The work permit that the Mexican government gave me expired after a year. So I can’t work at places like the butcher shop because now I’m undocumented here—we don’t have papers anymore. I tried to renew the permit but couldn’t.

Now I’m picking up trash. I go from dumpster to dumpster looking through the garbage to see what I can find that then I could clean up or fix so I could sell them. I use that money to feed my family. I also used some of it to buy a few vegetables a little while back, and I’ve set up a few crates on the street where I sell onions, tomatoes, and papayas, trying to make enough to eat every day. We are in desperate need of help. My kids need food. My oldest son asks me why we still can’t enter the United States, because he wants to study there.

We’ve been to court in the United States a total of six times, but since the pandemic, we haven’t been able to, so we just show up at the border and they tell us to come back next month. We’re going to keep going until the end, even though they’ve postponed our court date five times since the pandemic started. What I really want is to be able to go to court, because we finally found a pastor who lives in the United States and she connected us with an organization that can provide legal help. She lives in Oregon and even said she would take us in.

People have told me that there are elections going on there, and from what I understand, Trump isn’t going to win. People tell me that the new candidate has a lot of support, and I know how much can change with a new president. Maybe that new president can let us in.

In 2012, President Obama created Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), allowing certain undocumented immigrants who were brought here as children to apply for a two-year work permit that also protected them from deportation. More than 700,000 people have since received and renewed DACA. But in 2017, the Trump administration announced it would dismantle the program—a move that was quickly challenged in court. On June 18, 2020, the Supreme Court blocked Trump’s attempt to end the program but sent the matter back to the administration for further consideration.

Reyna Montoya, 29

From: Mexico

Lives in: Mesa, Arizona

Reyna Montoya as told to Fernanda Echavarri

I ended up migrating to the United States by the age of 13, but before that, at the age of 10, we moved from Tijuana to Nogales. I was just picked up from school one day. No explanation was given to me. Later on, I found out that my dad had been kidnapped by Mexican police. And as a little kid I didn’t know anything. I would just see my mom’s face and my dad’s face; they were always worried after that.

I learned about this years later, when my dad was in deportation proceedings in 2012—I started piecing everything together, because we were trying to figure out how to keep my dad here through asylum. There were a lot of questions like, “Why did you migrate?” So then everything made sense.

We always had tourist visas, my mom, my brother, and I, so my migration was a little bit different. I remember just crossing the border in a car. But I learned pretty fast that not knowing English meant that I wasn’t going to be valued, and that I was always going to be excluded from opportunities. So I was in ESL classes, and within a year and a half I was kicked out of ESL. I don’t know how, but I learned English pretty fast.

Still, high school was one of the most difficult moments of my life, where my identity was formed around being a good student and paying it forward for my parents. I had to make sure that my parents’ sacrifices were worth it. But when senior year of high school came, I realized I couldn’t pay in-state tuition when I went to college. It didn’t matter that I had a 3.8 GPA. It didn’t matter that I was involved in all these extracurriculars. I felt deceived and lied to by my teachers. I was like, “You promised me that if I will work really hard, the future would look bright,” but that was not my reality.

DACA didn’t exist then, and I have mad respect for my parents. I don’t think I would have had that much drive and hustle. My mom and dad, who didn’t even graduate high school, found out that there was this private scholarship—and that’s how I got into college.

At Arizona State I met other Dreamers, and I started advocating for the DREAM Act in 2010. The DREAM Act failed, and there was a lot of heartache and disappointment, but I decided to stay involved. When the DACA announcement was made on June 15, 2012, I led a press conference. I was terrified. President Obama made the promise that if we came forward in good faith, our information was not going to be used against us or our parents. Call it naivete, but a lot of us believed in that promise.

When I got DACA a few days after the election of 2012, I felt a lot of hope. While it wasn’t what we wanted, we were hoping that this was a step in the right direction that would enable us to eventually, maybe down the road, get immigration reform.

During the Trump era, having DACA has meant anxiety and broken dreams. It’s meant betrayal, a lot of betrayal. We were promised this, and now I can be deported. It became real.

Even talking about it now, my hands are getting sweaty and my throat chokes up, because it’s been very, very difficult. I’ve been in a romantic partnership for the past seven years, and he’s also a DACA recipient, so it’s that constant anxiety and fear. It’s like I feel someone is holding my heart really tightly.

When I think about all the people that I encouraged to apply for DACA, it feels really heavy now that there’s been a betrayal from the government, knowing that ICE has our information and what this administration can do with that. It’s very, very scary.

Since Trump took office, he was constantly threatening to drop an executive order. Every Friday became a nightmare, from the Muslim ban to the leaked memo in February 2017 with his plan to end DACA. Then fast forward to September 2017, when Jeff Sessions officially announced the termination of the DACA program. It went from Trump saying, “I’m gonna negotiate with Chuck and Nancy” to him saying, “No, Chuck and Nancy don’t like me, they are not getting me what I want.” So it was just constantly reading the tweets, waking up at 5 a.m. and checking my phone, instead of saying my morning prayer, or my morning meditation. Then it became about the Supreme Court, waking up every morning and tracking the Supreme Court through the blog and Twitter. Then finally I could catch my breath, when the Supreme Court ruled in our favor a little bit. But still, what does that mean? Is the Trump administration actually gonna follow protocol? They reduced our two-year work permit to one year, so it’s scary.

It’s been such a roller coaster of emotions. I’ve started going to therapy. It definitely has been very difficult for me to not only to experience that as someone who is impacted, but having to answer to many Dreamers who come with questions and have very different life experiences. When I think about those Dreamers who are isolated and don’t have the resources to get mental health support, my heart gets really heavy.

I hope those people that said that they care and that they voted, because they’ve heard stories like mine, that they don’t forget about our pain.

The Trump administration has made it nearly impossible for Mexicans and Central Americans fleeing violence and persecution to win asylum. Héctor (a pseudonym to protect him from retaliation) came to the border last year to ask for asylum and spent more than a year at an ICE facility in Louisiana before being deported. I spoke to him in September, when he was in Mexico attempting to sneak back across the border.

Héctor (a pseudonym)

From: Honduras

Héctor as told to Noah Lanard

I’m from a rural part of Honduras. My parents were coffee growers. I went to the police academy in 2015 and ended up working in investigations. While I was on duty one day, we went to look at a semi-trailer that had been abandoned on the highway. The decapitated body of the driver was later found nearby. We got surveillance footage and saw that three cars had been following his truck. One of them belonged to a police officer. Then we got footage showing two police officers using the victim’s credit card. One of the things they bought was a cellphone. We tapped it and heard them talking to other police officers. A superior told me to be careful.

My wife and I started getting threats after I turned in the preliminary results of the investigation. They started sending photos of my car and our apartment. They even sent photos of a new apartment that we moved into to hide from them. We fled about five days later and left our 8-year-old daughter with my dad.

I paid a friend about $7,000 to get us here. We had $3,000 in savings. I got a loan for $2,000, and we sold our car to a friend. My brother gave us some money as well. About 10 of us traveled through Guatemala and Mexico on a bus. It took 10 or 12 days to get to the border.

After crossing the river, my wife and I turned ourselves in to request asylum. I spent 14 days sleeping on the floor in a temporary detention center in McAllen, Texas. My wife was there for about 20 days. It was hard. There’s wire mesh, a cement floor, and two toilets for up to 80 people. Sometimes, we took turns sleeping because there wasn’t enough space for all of us to lie down. They give you a frozen bologna sandwich and some juice. It gave me diarrhea, and I had to clean myself off with toilet paper. We couldn’t bathe. We couldn’t brush our teeth.

My wife was moved to a detention center in San Antonio and was released after a month on a $1,500 bond. I ended up in the hell that is [a detention center in Louisiana]. I heard that it had been a prison until they converted it into an immigration detention center. When we got there in May 2019, the bunkers were dirty and smelled terrible. We’d been told that we’d get out on bond quickly. But when we talked to other people in the yard, they said we were going to be there for the long haul. We didn’t believe them, but that’s what happened.

It took three months for me to have my first court date. We’d take strips of plastic from garbage bags and braid them together to make bracelets and shoes to distract ourselves. Sometimes breakfast was served at 2 in the morning. Other times at 5. Nothing was normal.

The judge denied my bond because she said I was a flight risk, so I spent Christmas locked up. My final court date was in March. The judge told me that I’d only been threatened for a short period of time and that my boss had promised to help me. Because of that, she didn’t consider it persecution. The hearing was quick, maybe an hour and 40 minutes. After denying me asylum, she asked me if I wanted to do an appeal that would take six to eight months.

That was when the coronavirus hit. I said no because I couldn’t handle more time in detention. Many of us were sick. We had terrible headaches. Pain in our joints and bodies. Fevers. It was horrible. Horrible. They didn’t give us medicine. The virus hit all of us. I hid my fever from the nurses so that they didn’t send me to solitary. Instead, I did what they do in my hometown to fight fevers: drinking very bitter coffee without sugar. Without coronavirus, I would have appealed.

I spent three months waiting to be deported. I never imagined that I’d spend so long detained. There were people who’d committed crimes who got out on bond. We were abandoned.

After being deported, I spent just over two months at my dad’s house planning my return to the border. I slept in the living room to protect my family. I was thinking that, if the corrupt cops came to get me, they’d see me in front of the house and kill only me.

When we tried crossing a few days ago, the Border Patrol caught most of the people I was with. We had to run away from them, and I wound up sleeping in the mountains in Mexico, where a snake almost bit me. While we were coming back across the river, the water was up to our necks and one person nearly drowned.

The future is uncertain. I think four or five of us will cross again soon, and I’m a nervous wreck.

A week later, Héctor texted to say he’d made it across. He was on his way to reuniting with his wife. He’s now working in construction.

Following his campaign promise to bar Muslims from entering the country, President Trump enacted a travel ban one week after his inauguration. The policy was blocked in court, as was a second version. But in 2018, the Supreme Court upheld a third ban that restricts travel and immigration from six countries, including Iran.

In theory, the current ban allows for exceptions for people like Masoud Shameli, the son of Iranian immigrants living in Orange County, California. In practice, waivers have often proven impossible to obtain. Here’s Masoud’s father, Reza, and his older brother Ehsan.

Masoud Shameli, 34

From: Iran

Lives in: Isfahan, Iran

Reza Shameli and Ehsan Shameli as told to Noah Lanard

Reza: We’re from an ancient Iranian city called Isfahan. I worked for a bank for about 30 years until I retired. When my sons went abroad to study, they persuaded us to come here. God helped, and my wife and I were able to get our green cards through the diversity visa lottery. We’ve been married for 42 years. When you reach this age, the only thing that’s important to you is your children. Four of my five sons are here at the moment. The thing that makes us worry is that one of them is still in Iran.

Ehsan: My older brother, Amin, came to the US in 2003 to pursue his PhD in electrical engineering. I went to Canada for my PhD in mechanical engineering. Five years after me, my brother Ashkan came to Canada for his PhD in mechanical engineering as well. Masoud is one year younger than Ashkan. He graduated from his master’s program and started working in Iranian civil engineering. My youngest brother, Ali, came to the US with my parents when they came here via the visa lottery. He studied some English, then got into a PhD program in computer science and management. And now he’s been admitted to MIT for his postdoc.

Masoud lives in Isfahan. The situation is really bad because of the US sanctions. There’s a lot of industry in the suburbs—refineries, petrochemical plants—and it could become a target if there is a war with the United States.

All of the news about conflict with the United States creates a significant level of distress and anxiety, particularly for my parents. My dad has heart issues. He’s 75 years old, and they’re both kind of in a depression.

Reza: When they were kids about 35 years ago, we were at war with Iraq for eight years. Our house was hit two or three times. Buildings around us collapsed. We have very bad memories of those days.

Ehsan: I remember everything shattering. Part of the wall fell down. We all had to flee the city.

Reza: We always follow the news. We knew that politicians say things during the campaign, then do something different after they get elected. So I didn’t think that Trump was serious about the ban.

Ehsan: Masoud started the green card process in 2011. Because he’s in the queue for adult sons of US immigrants, it takes a long time. The election happened right when his turn came up. The travel ban was really bad timing. If the travel ban had happened three months later, Masoud would have been here for two years now.

Reza: When the travel ban happened, my wife and I got sick. Really sick. It was very stressful. We couldn’t sleep. It was devastating.

Ehsan: It got to the point where we had to take my parents to the doctor. My mom was so stressed that she collapsed a couple of times.

Reza: When I have trouble sleeping, I’m worrying about my children, about their fate, about their futures. Sometimes, I have to take a pill and walk around to be tired.

Ehsan: The idea that the travel ban was designed to stop terrorism has landed particularly hard on my parents. They can’t imagine that their son is being taken away by an accusation of terrorism. How could we be terrorists? We’ve been working in prominent companies in the US. I have many US patents. My brother has US patents. I was a professor at a university teaching US kids how to do engineering and physics.

When the ban happened, I remember thinking that if somebody in the government is violating the law, there is another branch of the government who stops it. You are in a country of laws, not a dictatorship. I remember my brothers and me telling our parents, “Don’t worry, we’re protected by the law. This court system is very fair. The government has to respond.” But you know the history.

We eventually had this family discussion about, what do we do? We hired a lawyer. Katie Porter, she’s a congresswoman in our area, we meet with her staff at least every few months. We wrote letters to the president’s office. Everything we could possibly do as citizens. We wrote a letter to Pompeo’s office. To no effect.

Reza: When you are in a situation like Masoud’s, you’re not on solid ground. You’re neither here nor there. He’s wanted to get married, but he could get a letter any time saying that he’s been approved. What can he do?

Ehsan: If Masoud gets married, then his case would become a different case. It would take much longer to process. So because of that, his life has been on hold.

Reza: Before the coronavirus hit, we used to go to Iran every year to see him. But because of COVID-19, it’s been more than two years since we’ve seen him. It’s the longest I’ve ever gone without seeing him. We communicate over video chat almost every day.

Ehsan: Normally, the plane tickets to visit him are about $1,400 per person. The last time that we all went as a big family it was me and my wife, my brother and his wife, and the other brothers, plus my two kids. You’re looking at like $11,000 just for tickets. Then there’s the cost of talking to lawyers. That’s not cheap in California.

The thing that’s very directly impacting our family is immigration policy. There are other issues like taxes, but 5 percent more or 5 percent less doesn’t change the way that we’re living. But the fact that one of our family members is directly separated from us because of this policy makes a huge difference for us. At least based on what you see on the news, it doesn’t seem that the immigration policies are going to get any better, or that this travel ban is going to get lifted, if Trump is reelected. It seems like he’s going to go even more in the direction he’s already gone.

I remember the day that Joe Biden said that he’d lift the travel ban on his first day in office. We were all texting it to each other. I think a lot of people are looking forward to that day. Not only us.

More than 350,000 people in the United States have temporary protected status, a program in which the US government offers relief to immigrants from certain countries who fled civil war, environmental disaster, or an epidemic to live and work here legally. Typically, TPS can be renewed every 18 months, and tens of thousands of people have renewed it multiple times over the last 30 years, planting roots and raising families here. But in his first year in office, President Trump ordered an end to TPS. After a court challenge, the administration said it would extend TPS through January 4, 2021, for the majority of TPS holders from El Salvador, Honduras, Haiti, Nepal, Nicaragua, and Sudan.

Maria Elena Hernandez, 60

From: Nicaragua

Lives in: Broward County, Florida

Maria Elena Hernandez as told to Fernanda Echavarri

My family came fleeing the civil war in Nicaragua in 1979, because they served in the military and they had to seek refuge here in the United States. We saw this country as a defender of human rights, so we felt safe here.

Since I came to this country, I integrated and saw it as my second home. I haven’t gone back to Nicaragua once. I would feel like a foreigner there, and I wouldn’t feel safe, because I know that people who go back after living here so long are seen differently, and it could end really badly. My life is here; this is my community.

I work doing housekeeping at a university, cleaning offices, and I’m also a representative for our union, where we’re mostly Latinos. We work hard cleaning, especially in this pandemic. We’re keeping the university clean so that students can be safe. Every day, we face uncertainty and fear of getting the virus and passing it on to our families, but we’re considered essential workers.

Now President Trump is considering us disposable, and I don’t think that’s fair. We’ve given our lives to this country, and we should be recognized because we’ve worked legally and have contributed to the economy.

I used to live in peace, but since Trump took office I feel that at any moment they could take me away. I fear that they could just separate me from my family. Before Trump, I had safety. I knew that I had TPS and felt that my work was recognized. But the uncertainty now is terrible. One day he says one thing, the next day he says another.

Back in 2018, Trump said TPS was over—but then it was appealed and instead it got expanded by a year, which would mean it ends January 5, 2021. So all this uncertainty continued. Then, not that long ago, we were told that it was revoked again, but it’s being appealed again. All that keeps us unstable, because we don’t know what’s going on in the courts.

This year my brother, his wife, and I were thinking of buying a house together. I’m divorced, and I live with them, so we wanted to buy a house to live more comfortably. But with this situation, we didn’t do it because of this uncertainty that TPS might end in January.

Sometimes I watch the news and I see how disparagingly immigrants and Latinos are talked about, and I feel terrible. At the same time, I get strength because I know there are a lot of people who support us and who recognize the work we do. We’re not living here for free: We’re working, we’re contributing with our taxes and our culture. If we’re doing good here, why can’t we keep doing so in peace here? I’ll respect whoever the next president is, but the respect has to be mutual.