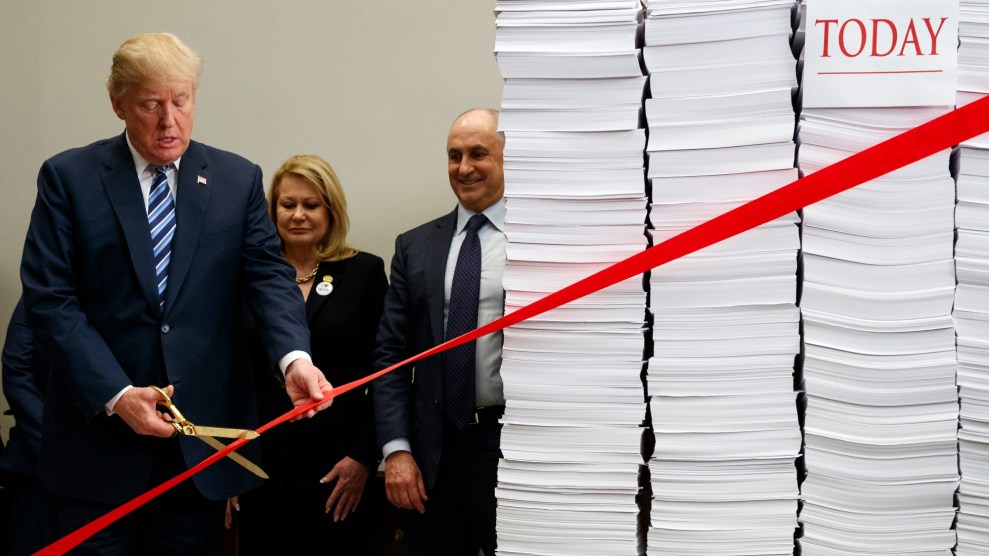

Evan Vucci/AP

A year into his presidency, Donald Trump stood in the Roosevelt Room of the White House next to towering stacks of white paper wrapped in a bright red ribbon. Flanked by Cabinet members, he explained that the paper symbolized federal regulations. “Within our first 11 months, we canceled or delayed over 1,500 planned regulatory actions,” he boasted, then urged “every Cabinet secretary, agency head, and federal worker” to slash even more regulations over the next year. “Let’s cut the red tape. Let’s set free our dreams.” He took a giant pair of gold scissors and, with a TV star’s flourish, snipped the red ribbon wrapped around the paper stacks. The audience burst into applause.

In the three years since the Roosevelt Room stunt, the Trump administration has gutted rules on everything from clean water protections to affirmative action. But more than anything, Trump’s deregulation has targeted financial reforms. He signed a law easing rules for major financial institutions that were enacted as part of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street reform bill to prevent the kind of risky investment behavior that helped cause the Great Recession and required a taxpayer-funded bank bailout. The directors he appointed to lead the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau eased restrictions on predatory payday lenders and weakened protections for minority borrowers.

The list goes on.

I spoke with Graham Steele, director of Stanford Business School’s Corporations and Society Initiative and a former Senate banking committee chief counsel, about the last four years of financial deregulation, what they mean for the COVID-era economy, and how a Biden administration could rebuild protections for consumers.

After the 2008 financial crisis, Congress erected a regulatory infrastructure that included Dodd-Frank and the CFPB. What do you see as the biggest shift in that infrastructure to have come out of the last four years?

In the post-Dodd-Frank era, there was this posture by the financial agencies that the stability of the financial system and minimizing the risk to the public was the prime concern, and banks’ shareholders and profits were the secondary concern. And we’ve seen that general posture flip amongst the regulators in a way that says the rules need to be more accommodating of private banks. That there needs to be more deference on the part of regulators that bank management know what they’re doing. That they’re mature adults who can handle themselves. And they don’t need the government coming in second-guessing them.

What were the biggest specific changes to banking regulation?

Capital is number one on the list. Strong capitalization [rules requiring banks to reduce risk to the economy by holding more capital] was the centerpiece of financial reform. Now we’ve backslid. [The Trump administration] set the default position that the primary objective is letting banks pay out to their shareholders, instead of making sure that they’re building the financial capacity to support the rest of the economy.

The Volcker Rule [a part of the Dodd-Frank bill separating commercial and investment banking] is number two. It was supposed to be one of the things that fundamentally changed Wall Street’s business model to make them less about making risky bets on their own behalf, to try to reorient them more to serving customers. Now, the rule is still there in name, but in practice, it has lost a lot of the teeth that it had.

What has all this meant in the COVID recession?

Debt collection rules that have been rolled back by the Consumer [Financial Protection] Bureau have been really harmful, and are particularly harmful to people in this moment, given the massive amount of debt in the economy and the hard time people are facing. We also have an economy and a credit system that is deeply unequal along racial lines. And that is an area that requires affirmative remediation. Across the board, this administration has been out to lunch on, if not fundamentally hostile to, all of those sorts of obligations.

Now the economic response to COVID is further exacerbating that: Some aid programs tied to COVID rely on the financial system to disseminate that aid to people in their communities. If they don’t have access, they’re not going to get their money as quickly, and they may never get their money at all.

If Trump wins the election, does his administration’s deregulation set the country up for another 2008-esque crisis or a government bailout?

Yes. That’s the most likely scenario. If we continue on this trajectory, eventually there are pockets of the economy that could become problematic, that then could lead to more [government] support for the banking system. It seems like things are okay for the time being. But the question is, how much longer are we going to be doing this and how bad is it going to get? How high is unemployment going to get? How bad are defaults, foreclosures, and evictions going to get? Even if Biden wins, if there’s no stimulus between now and Inauguration Day—if this goes on for much longer, then I think that there will be problems in the banking system.

And I want to be clear that just because banks haven’t caused this crisis, there are a whole bunch of institutions and private businesses that have paid out a lot to their shareholders over the last few years—that have essentially sacrificed building up their own financial resilience in pursuit of additional profitability and additional shareholder returns. So while some of these institutions aren’t necessarily responsible for causing the particular circumstances that are challenging right now, they are responsible for prioritizing shareholders over paying their workers more or retaining earnings so that they have a rainy day if something bad happens.

If Biden wins, where should his administration begin in rebuilding protections for consumers?

There are longer-term structural issues that they should look at to make the system more just and equitable. One area is reorganizing the CFPB so that [the] fair lending [department] is back in enforcement where it can take strong action against the industry. Reviewing a lot of the weak rules that have been passed during this era and updating them. And then going farther: rewriting the rules around payday lending, around debt collection, reforms around credit reporting. Those are all really important areas.

On the banking side, I think suspending bank dividends will be really important to make sure the banking system is recapitalizing itself right now. The longer-term goals [should be] to rebuild resilience, essentially building up a public banking infrastructure: Give more low-income folks access to the banking system, either by having bank branches at public banks, at the post offices, or giving people access to accounts at the Federal Reserve. So that when someone needs to apply for a loan, they already have a banking relationship. I think a top priority should be thinking about, how do we use a public banking system to fill in the cracks where people’s needs aren’t being met? How do we have a vibrant small banking community? How do we bolster credit unions and community development financial institutions so they get more direct support, and we’re not just relying on a handful of really behemoth Wall Street institutions?