Well into the 19th century, the word “inflation” referred mostly to bodily phenomena. It meant an enlargement of hot air in your stomach, a cancerous growth, a swollen organ, an imminent fart. Samuel Johnson’s dictionary from 1755 called it “the state of being swelled with wind.”

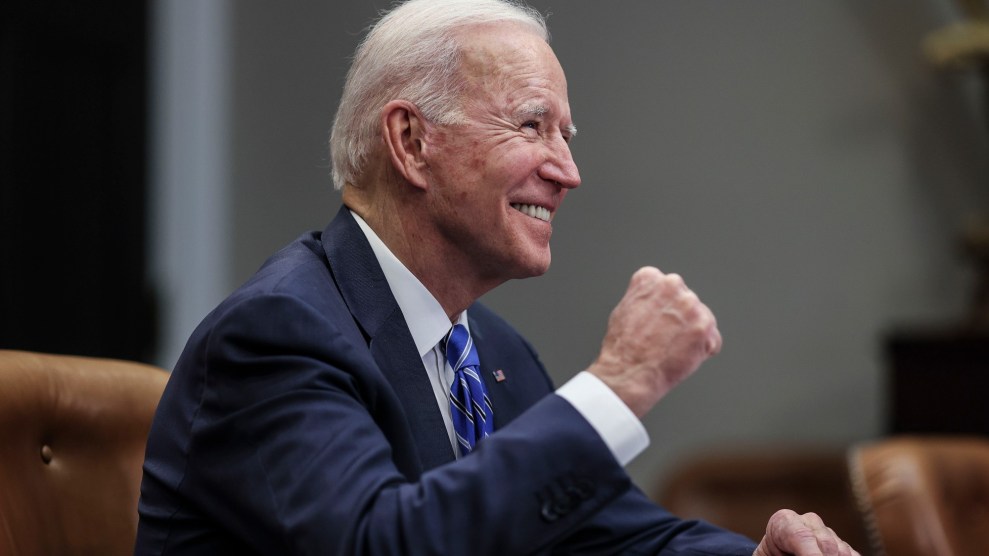

Today, inflation tends to be used in an economic context, denoting an increase in the price of goods and the resulting loss in purchasing power. Five percent inflation means that $1,000 in June 2021 can buy you 95 books; before, it got you 100. Yet the word has not drifted so far from its roots. It’s still described as an illness in our body economic, a toxic byproduct of gluttonous government spending and bloated wages for workers. The response from some quarters to President Joe Biden’s fiscal policy proposals, like his massive COVID relief packages and the $2 trillion infrastructure bill, has sounded like a physician’s diagnosis. The Economist wondered if the American economy would grow so fast it’d risk running a “fever”; policymakers worried the economy is “overheating.” Out of such metaphors are inflation hysterias made.

Inflation in an economic sense took root in the lexicon after the Civil War, when gold bugs and “inflationists” fought over whether to put more money in circulation. A party arose to fight for inflation: the Greenbacks (named for the new currency), who joined with labor interests. On the other side were business interests—“sound money” men who saw inflation as a personal affront. One famous tract said paper money was “clamored for as a new dram is called for by a drunkard.” Andrew Dickson White, a founder of Cornell University, compared the loss of “thrift” from paper currency adoption as “a disease more permanently injurious to a nation than war, pestilence, or famine.”

For Michael O’Malley, a professor at George Mason University, the 19th-century arguments rhyme with Reagan-era demagoguery about “welfare queens driving Cadillacs.” And they were used to similar effect. As W.E.B. Du Bois explained, Reconstruction fell amid charges of corruption from former Confederate landholders, little more than veiled complaints that “poor men were ruling and taxing rich men.” Said O’Malley: “The alleged corruption of greenbacks is connected to both paper money—or excessive debt—and racial equality.”

It was the project of 20th-century reactionaries to obscure the distributive struggles contained within inflation. In 1963, Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz published their tome, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. They found that each depression had coincided with a mismanaged supply of money: We’d inflated wrongly sometimes and deflated wrongly other times. In doing so, Friedman and Schwartz “posed inflation as an entirely technical matter,” said Ellen Frank, a lecturer in economics at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. A just-so story emerged about how low unemployment and higher wages inevitably result in inflation, a framing in which unemployment has a “natural rate” but inflation is always an ill to be eradicated. As one conservative joked before Congress, even God wants inflation to be zero.

Thus the austerity of the 1970s and beyond was offered as a technocratic fix. Doctorates got to play doctor and prescribe a hard medicine for America’s indigestion. Paul Volcker, installed as chair of the Federal Reserve by Jimmy Carter, hiked up interest rates, allowing bankers to make a killing and stalling the economy. The harms were an afterthought, like the side effects enumerated at the end of a pharmaceutical commercial: lower wages, higher unemployment, less spending on the welfare state. Examples of inflation run amok—Weimar Germany, Hungary after World War II, Zimbabwe in the late 2000s—underscored the philosophy. Forget the German war debts and the 1970s oil shocks. Forget that there is no strong agreement among economists about what causes inflation. Do you want to become a failed state because of a higher minimum wage?

Inflation is money losing value; it is the wealth of the rich eroding. Yes, it can spiral out of control. But it also eats away at debt—for students now, for farmers in the late 1800s, for our country during World War II. Yet these aims are always coded as fake or greedy. Beryl Sprinkel, an economist in the Reagan Treasury department, described inflation as “stuffing a kid with too much food” to the point of being “sick.” When Senator Mitt Romney hit back against President Obama’s quantitative easing—a post-2008 recession measure to increase the money supply—he warned it was an “artificial” boost and a “sugar high.”

“We regularly use the metaphor of illness to describe the problem of inflation,” the economist Albert Heilbroner Jr. lamented in 1979. It had become “the great besetting ailment of Western society” and the “global malady of capitalism.”

We are still living with the wreckage caused by the old consensus. “We’ve lost the industrial heartland of the country,” said the economist James Galbraith, a longtime enemy of inflation hawks. “That’s what we’ve lost.” It was never just about the money. Inflation hysteria is always class war of one kind or another, waged on behalf of the asset-holders against perceived forces of “social destabilization,” O’Malley said. “It’s about the wrong kind of people getting too much stuff.”