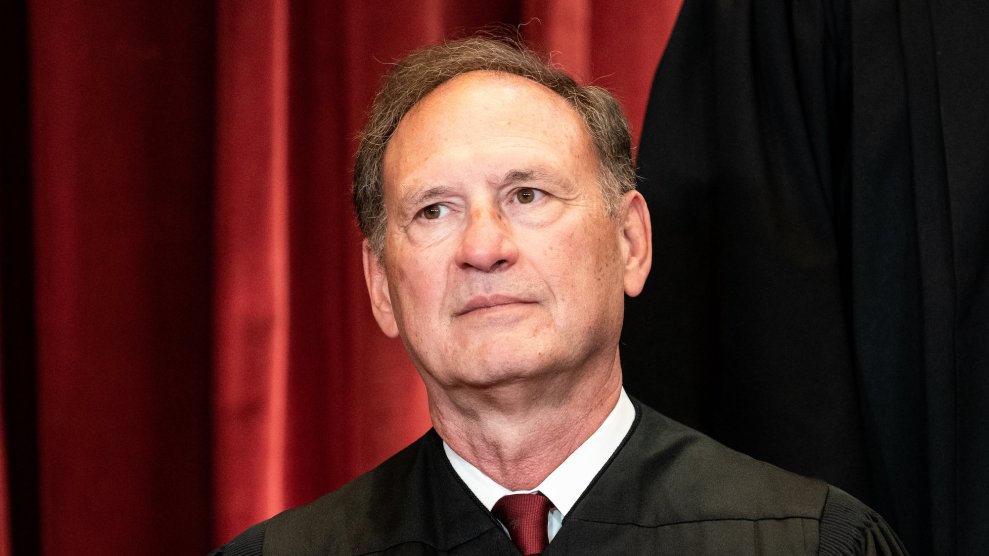

Justice Samuel Alito ruled on Thursday that Arizona's restrictive voting laws didn't violate the Voting Rights Act. Erin Schaff/ZUMA

The Supreme Court upheld two Republican-backed voting restrictions in the state of Arizona on Thursday, giving a green light to Republican efforts to make it harder for Democratic-leaning constituencies to vote.

The court gave its blessing to two laws passed by Arizona’s GOP-controlled legislature—one preventing anyone but a voter’s family member or caregiver from returning a mail-in ballot and another one throwing out votes cast in the wrong precinct—that had been struck down by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in January 2020 for discriminating against Native American, Latino, and Black voters.

Justice Samuel Alito, writing for a 6-3 conservative majority in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, argued that disparate impact among racial or ethnic groups isn’t enough to make voting laws illegal. “The mere fact that there is some disparity in impact does not necessarily mean that a system is not equally open or that it does not give everyone an equal opportunity to vote,” he wrote in upholding the Arizona restrictions.

But the significance of this case reverberates well beyond Arizona. Seventeen states have passed 28 new laws this year restricting access to the ballot, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. In response, Democrats have filed a flurry of lawsuits to block them. Republicans have already admitted they are passing such laws for partisan gain: During oral arguments in the case, Michael Carvin, a lawyer for the Republican National Committee, said that striking down restrictions on voting “puts us at a competitive disadvantage relative to Democrats.” The decision on Thursday signals that a conservative-dominated judiciary—which includes three Supreme Court justices nominated by Donald Trump—will not stand in the way of the greatest rollback of voting rights since the end of Reconstruction.

“What is tragic here is that the Court has (yet again) rewritten—in order to weaken—a statute that stands as a monument to America’s greatness, and protects against its basest impulses,” Justice Elena Kagan wrote in her dissent, joined by the court’s other two liberal justices.

Alito has a long history of advocating for GOP policies that make it harder to vote. In 2018, he wrote the opinion upholding Ohio’s policy of removing infrequent voters from the rolls, which voting rights advocates said turned voting into a “use it or lose it” right and opened the door to more aggressive voter purging by Republicans.

During the 2020 election cycle, he repeatedly sought to counter laws expanding mail-in voting. Days before the election, he wrote that the Supreme Court should hear a case filed by Pennsylvania Republicans challenging the legality of mail-in ballots in that arrived after Election Day, “to prevent the election in Pennsylvania from being conducted under a cloud.” (The Court decided not to take the case.) He also stated that he would have ruled against efforts to make mail-in voting more accessible in South Carolina and Rhode Island. (The court’s majority sided partially with Republicans opposed to the mail-in voting changes in South Carolina and against them in Rhode Island.)

Alito has also repeatedly backed redistricting maps accused of discriminating against voters of color. In 2018, he wrote the opinion to uphold redistricting maps for the US House and state legislature drawn by Texas Republicans that a federal court found were enacted with “racially discriminatory intent” against Latino and Black voters. In the 1980s, Alito explained that he had become interested in constitutional law because of his opposition to the rulings by the Warren Court in the 1960s, in particular its “one person, one vote” cases that rectified widespread racial and partisan gerrymandering enacted by states to preserve rural white political power.

The Brnovich opinion also represents the culmination of a 40-year effort by Chief Justice John Roberts, who served with Alito in the Reagan administration, to weaken the Voting Rights Act. As I previously reported for Mother Jones, as a young lawyer in Reagan’s Justice Department, Roberts led the administration’s push to weaken Section 2 of the VRA, which applies nationwide and outlaws the denial or abridgment of the right to vote on account of race or color, and was used to successfully challenge the voting restrictions in Arizona before the lower courts.

Roberts wrote 25 memos urging Congress to limit Section 2, arguing that smoking-gun evidence of intentional discrimination, which was difficult to find, was needed to strike down laws or overhaul elections systems that blocked people of color from voting or winning elections. “Violations of Section 2 should not be made too easy to prove,” Roberts wrote in 1981, “since they provide a basis for the most intrusive interference imaginable by federal courts into state and local processes.”

Roberts lost that fight when Congress reauthorized the VRA in 1982 for another 25 years, but he prevailed three decades later as chief justice, when he wrote the opinion gutting Section 5 of the VRA, which required states with a long history of discrimination to get federal approval for any voting changes. That 2013 ruling in Shelby County v. Holder led to a wave of new voter suppression laws in states including Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas. Twenty-six states have enacted new restrictions on voting since the Shelby decision, according to an analysis by Mother Jones.

Roberts justified his decision in part by pointing to the continued existence of Section 2 of the law. “Our decision in no way affects the permanent, nationwide ban on racial discrimination in voting found in Section 2,” he wrote. (The Justice Department sued Georgia last week under this provision, arguing that Republicans had intentionally discriminated against Black voters.) Yet by upholding Arizona’s voting restrictions, the Court has continued to weaken what remains of the country’s most important voting rights law.

In so doing, the court chose to dismiss the ways in which the Arizona laws had discriminated against voters of color, as I reported in March:

From 2008 to 2016, Arizona threw out more than 38,000 ballots because voters showed up to the wrong voting precinct, even though their votes for statewide offices should still have been valid. Arizona rejected more out-of-precinct ballots than any other state—a rate 11 times higher than the state with the second-most rejections, Washington. In 2016, American Indians, Latinos, and Black voters were twice as likely as whites to have their ballots thrown out for this reason.

Similarly, a law preventing anyone but a family member or caregiver from returning a mail-in ballot (what Republicans call “ballot harvesting”) also discriminated against Native Americans and Latinos, the Ninth Circuit found, since those communities more often lack reliable mail service and live greater distances from polling locations, requiring assistance to return their ballots. When the law was first passed in 2011, Arizona’s elections director told the Justice Department it was “targeted at voting practices in predominantly Hispanic areas.”

If not for Roberts’ 2013 decision gutting the Section 5 of the VRA, both Arizona laws would likely have been blocked by the Justice Department in the first place. Now it seems likely that the court will exempt all manner of new voter suppression laws from being struck down under the VRA, turning its back on protecting the voting rights of communities of color just like it did during the Jim Crow era.

The conservative majority’s ruling doesn’t strike down Section 2 of the VRA, but it does substantially narrow the path to invalidate new voting restrictions under the provision. “Section 2 does not deprive the States of their authority to establish non-discriminatory voting rules, and that is precisely what the dissent’s radical interpretation would mean in practice,” Alito wrote. “The dissent is correct that the Voting Rights Act exemplifies our country’s commitment to democracy, but there is nothing democratic about the dissent’s attempt to bring about a wholesale transfer of the authority to set voting rules from the States to the federal courts.”

But Kagan, in her dissent, argued that the court was overstepping its bounds in weakening Section 2. “The majority fears that the statute Congress wrote is too ‘radical’—that it will invalidate too many state voting laws,” she wrote. “So the majority writes its own set of rules, limiting Section 2 from multiple directions….This is not how the Court is supposed to interpret and apply statutes.”

Alito justified the ruling in part by raising the specter of voter fraud, which conservatives have repeatedly invoked in making it harder to vote, even though it’s been shown to be extremely rare. “One strong and entirely legitimate state interest is the prevention of fraud,” Alito wrote. “Fraud can affect the outcome of a close election, and fraudulent votes dilute the right of citizens to cast ballots that carry appropriate weight.”

Since the court’s conservative majority will not stop voter suppression efforts, pressure will increase on Congress to act. Two bills introduced by congressional Democrats—the For the People Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act—would stop many GOP voter suppression laws by enacting federal standards to make it easier to vote and restoring the preclearance provision of the VRA. But the more wide-ranging of those proposals, the For the People Act, was blocked recently by a Republican filibuster in the Senate, raising serious questions about how Democrats will combat voter suppression efforts if they don’t pass federal legislation and are unsuccessful before the courts.