It was 5 a.m. and still dark as we rolled west out of Santo Domingo, on a cool morning in May 2019. We rode through the tourist zone, past whitewashed Spanish colonial buildings, pointing our truck toward the Haitian border. A sliver of waning moon hung in the eastern sky.

After three decades, I’d returned to the Dominican Republic, pulled back by the haunting memory of a Haitian child. All stick legs and sunken eyes, he stood barefoot and shirtless under a fierce and pounding sun, surrounded by endless fields of Dominican sugarcane. His name was Lulu Pierre; he was 14 years old. I’d met him in March 1991, when I went to a Dominican state-run sugar work camp, known as a batey, to investigate widespread human trafficking and forced labor in the harvest. I’d visited a transit camp where Haitians were secretly processed. I’d read the human rights reports documenting the Dominican military’s role in transporting Haitian men, and sometimes children, to the harvest. But now I was seeing it for myself.

Just days before, soldiers had abducted Lulu at a market on the Dominican–Haitian border, thrown him into a pickup, and dumped him at the camp in the middle of the night. “If you want to eat,” the bosses told him, “you have to cut the cane.”

But Lulu couldn’t do it. He’d given up and turned to fishing in pesticide-ridden ditches beside the fields. “My mother and father don’t know where I am,” the child told us. “I want to go home.” Alan Weisman, then my reporting partner, and I gave a Catholic relief worker the equivalent of about $80 to try to get him back to his family.

We never learned what happened. But I’d thought about Lulu Pierre ever since, determined one day to return and find out if he ever made it.

“I think we will find Lulu,” declared Euclides Cordero Nuel from the passenger seat. It was growing light as I eased our truck onto two-lane blacktop, moving past lush stands of mango, tamarind, and pineapple, the flatlands turning to rolling hills as we neared the border. The island of Hispaniola, where Christopher Columbus first planted sugarcane in the New World, is divided into two nations: the Dominican Republic to the east, and Haiti to the west. Euclides, a Haitian Dominican journalist who agreed to help me look for Lulu, was 2 years old when I was last here. He grew up on a batey and cut cane at age 14 so he could buy shoes for high school. “I shared them with my brother,” he told me as we rolled along.

Over the last two years, Euclides and I mounted a broad search. We traveled to the market where Lulu had been snatched away from his family. We’d visited his Haitian hometown, stopping in at United Nations offices, city hall, the birth registry, and radio stations that agreed to broadcast live appeals. We zigzagged between the two countries on a road so broken that in long stretches it would have been faster to walk. And we made repeated trips to the old state-run bateyes, many now sold off and privatized, that had held Haitians like Lulu against their will. We never abandoned our mission, but we came to realize the story wasn’t just about Lulu. It was about the 68,000-some Haitian cañeros still in the fields, and their living and working conditions, especially under the island’s biggest plantation holder: Central Romana. Owned in part by brothers Alfonso and Pepe Fanjul, Cuban exiles who are now billionaire Florida sugar barons, Central Romana sugarcane is cut by Haitians, crushed and poured as raw sugar into the holds of vessels, and shipped to the Fanjuls’ ASR Domino refinery in Baltimore harbor. Then it’s packaged into 4-pound Domino bags, sent in bulk to industrial bakeries, and shipped by rail to be made into Hershey bars and other chocolates, cookies, and Halloween candies.

There’s no doubt Dominican sugar production has improved since I met Lulu. But according to government sources and human rights and labor advocates, Central Romana is most resistant to changing the deplorable conditions that have long plagued the industry. The company ships more than 200 million pounds of sugar to the US every year—far more than any other Dominican grower—and insists it treats its workers “with respect.” Public relations director Jorge Sturla says the company provides laborers opportunities to “improve their lives through secure, honest work.” The Florida-based Fanjul Corporation offered a statement claiming that “Central Romana is a highly respected corporate citizen in the Dominican Republic, and takes pride in its reputation for civic activities and ethical business practices.”

We came to see for ourselves.

We rattled down a long gravel road, straight as a string. On either side stood 8-foot-high stands of undulating cane, their weedy tops blowing in the wind. A train whistle signaled cars hauling stalks to the mill at company headquarters near the port at La Romana. Our destination: Cacata, or what Central Romana calls its “model” batey.

Cacata is one of about 100, according to a local missionary organization’s estimate, isolated company camps scattered among Central Romana’s 166,000 acres of sugarcane—a tract almost as big as New York City. Most of the workers and their families live in these bateyes, rising in the morning to work the cane in the punishing heat, clearing weeds, slashing and spraying the stalks. Nearly all are men of Haitian descent. Some were trafficked back in the day of Lulu Pierre; others were born here and live stateless; and others came from Haiti more recently, paying buscones to sneak them across the border. For years, the government has resisted providing legal status to people of Haitian heritage in the country, even those born there. An estimated 200,000 people, who for generations have been demeaned by race and class, are stateless.

For the men in their camps, Central Romana is the state. Their bateyes are patrolled by armed company police, empowered to evict. Central Romana owns the land where the Haitians work, the railcars where they weigh and load the cane stalks, and the dwellings where they sleep. They are miles from the nearest Dominican town not controlled by the company. Central Romana repeatedly refused requests for an interview or a tour to help me understand how it operates today. But two workers at a local charity founded by Alfy and Pepe Fanjul’s sister, Lian, spoke glowingly of Cacata, urging us to visit.

In Cacata we walk the quiet streets, laid out in a grid about a mile long. At first we see modest well-kept houses, kids playing stickball, a child singing to Jesus, families relaxing—the kinds of uplifting images promoted on Central Romana’s website. Many homes have electricity, and new potable water taps are accessible to all.

But as we walk deeper into Batey Cacata, we reach a grim-looking line of concrete barracks and, behind that, rows of dilapidated housing. Nearby, the Dominican supervisor lives in a large, solidly built house with a front yard big enough to fit several cane workers’ homes. “You can see, in Cacata, there’s a segmentation of the people,” Euclides says.

We keep walking. Soon we meet two old men sitting on broken plastic chairs in front of a slumping tin-roof shack. Euclides greets them warmly. After welcoming us in their native Creole, Julio and Cardenas (they asked us not to use their real names, for fear of retaliation) tell us they remember the horrible days of massive human trafficking and child labor: By the time I was last here, in 1991, they’d already been on Central Romana’s plantation for a decade.

Much of that chaos is in the past, they told us. Because of international pressure, few if any children still work the fields. The brutal trafficking rings, run in large part by the Dominican military, have been disbanded. But for Julio and Cardenas not much has changed. They are paid a little more than $3 for each metric ton, or 2,200 pounds, they harvest. “On a good day, I can cut a ton,” maybe a little more, Cardenas tells us. He’s almost 80, and Julio isn’t much younger. Yet even though Central Romana deducts government pension funds from their paychecks, they say they’ve never seen one peso.

“It’s not my fault I’m working,” Cardenas says. “I made requests for my pension, but I don’t have it.” Without proper working papers, they are trapped in the batey and too vulnerable to seek other work.

We ask the men if their bosses treat them well. Cardenas chokes back tears and stabs the hard ground with the point of his machete. “I’m not good,” he finally tells us. “You can see how they treat us here as a Haitian. Now if you have to go to the hospital, you have to have your own money to spend on your sickness…If you don’t have money, you’re going to die.”

Just then two armed men pull up on a motorcycle. They’re from Central Romana’s private security force. “Señor, what authorization do you have to be asking questions?” the lead officer asks us. “You are not allowed to be here without the authorization of the company. This is a private batey.”

“You guys have to understand,” the second guard adds. “We’re protecting interests here.”

Batey residents, with one man showing a burn scar.

Central Romana has plenty of interests to protect.

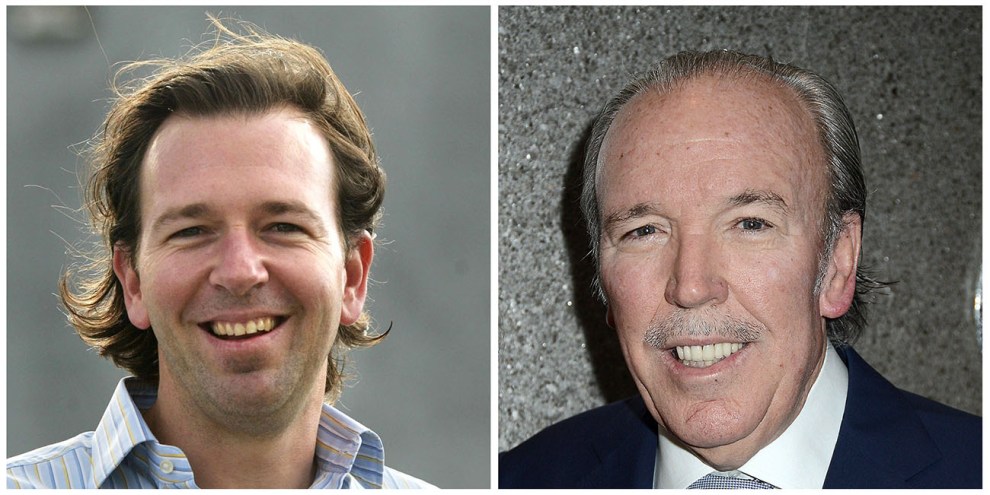

At the top of the company’s sugar chain: the Fanjul brothers, Alfonso and Pepe, who acquired it in 1984. The wealth generated by their 100,000 metric tons of annual imports to the United States, built on the sweat of men like Julio and Cardenas, has helped make them billionaires and build worlds of luxury. In the middle of Central Romana’s cane fields sits the Casa de Campo resort, a playground for A-list celebrities, European royalty, and former US presidents, who can rent villas, shoot pigeons, play golf and polo, or pilot a yacht into the sparkling Caribbean. The brothers live in seaside mansions in West Palm Beach, where Alfy also keeps a $23 million, 157-foot yacht. Pepe is partial to long stays at a London hotel, paying thousands of dollars per night. The family hosts charity balls, doling out millions to charter schools and day care centers, and tens of millions to politicians, who oversee government programs that repay them many times over. Speaking on the Senate floor, John McCain once called them the “first family of corporate welfare.”

Pepe Fanjul, Jr and Pepe Fanjul, Sr.

Taylor Jones/Palm Beach Post/ZUMA; Robin Platzer/Winimages/Photoshot/UPPA/ZUMA

Fanjul family members at their Casa de Campo resort, January 1990.

Slim Aarons/Getty

The wealth that Central Romana throws off gives it a kind of political and economic autonomy in the Dominican Republic; essentially it’s a state within a state, with deep ties to the country’s governing and commercial elite. The president of the Fanjuls’ Dominican operations later became the country’s vice president, foreign minister, and ambassador to the US. The former Dominican president repeatedly made use of the Fanjuls’ private jet.

As a practical matter, “The company is the judiciary. They are the police. They are the ones who rule over everyone’s life,” explains Christopher Hartley, a Catholic priest from Spain who became an advocate for the cane workers while posted in the Dominican Republic. “They decide who can stay in the barracks, who has to leave the barracks.”

Despite such restrictions, over the course of six trips, Euclides and I managed to visit more than two dozen of the company’s work camps, often not stopping for long, trying to keep two steps ahead of the armed guards. The original inhabitants of Hispaniola, the native Taino, defined “batey” as a village center, a gathering place. Today, the bateyes are outposts of flimsy wooden shacks and concrete barracks with cracked and crumbling walls. A mattress, sometimes just a sheet, on a bare floor, with a few clothes drooping from a piece of rope. A kerosene lamp or a candle melted down to the nub. Roofs riddled with holes.

Outside the cramped, dimly lit homes, just hard earth; when it rains, the dwellings become islands between massive puddles. In many bateyes, there are no fruit trees, not even subsistence gardens. Despite company denials, families in at least a dozen bateyes told us they’re not allowed to grow food. In a country with near-universal access to electricity, only one in 10 of Central Romana’s bateyes have power, by a local missionary organization’s estimate. There is little official documentation of conditions in the bateyes; seven Dominican government institutions failed to provide us with such statistics. The country’s Washington embassy sent us a statement boasting of great strides tackling poverty, but with no details on bateyes. One of the few sources of hard data is a 2013 report from the Dominican Ministry of Public Health, co-sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the US Agency for International Development, which found sharply elevated levels of tuberculosis, HIV, child malnutrition, and diarrhea. Another study indicated that nearly half the adult population in the bateyes have never attended school.

Perhaps all this is what Central Romana and its armed security are trying to hide.

A Central Romana batey.

Pedro Farias-Nardi

A family’s room. The parents use a bed; the children use a foam mattress on the floor.

Inside a house in a batey owned by Central Romana.

In 1997, Hartley took charge of a tiny parish in the Dominican Republic surrounded by cane fields.

“I’d been trained to say mass and baptize babies,” Hartley recalls. Though he had previously worked alongside Mother Teresa, gaining experience among the desperately poor, he says that until he came to the Dominican Republic, “‘grassroots’ wasn’t even in my vocabulary.” But after seeing conditions facing the country’s cane workers, he began to organize and speak out. “These people live, are born, and die in this paradise,” Hartley told a Canadian documentary team a few years after arriving. “But they live in it as slaves.”

By the end of the year, Hartley had partnered with Dominican human rights lawyer Noemí Méndez, who was born in a batey. Together they toured camps controlled by the powerful Vicini family, where his Haitian parishioners worked, and talked to cañeros about their rights and distributed copies of the Dominican Constitution. They both began to get death threats; Hartley says he would receive them until they drove him from the country in 2006.

Hartley eventually accepted posts in Ethiopia and South Sudan, but he remains active in the issue. In 2009, he joined forces with Charlotte Ponticelli, who had just stepped down as the Labor Department’s deputy undersecretary for International Affairs, a bureau known as ILAB. Two years earlier, she’d seen Hartley in a documentary and came away impressed. “A brave man,” she says. “Hardworking, devoted, dedicated, saintly.” ILAB was dealing with multiple other global trafficking issues at the time, but as she was leaving office, she wrote to Hartley offering her support. He promptly accepted.

Ponticelli guided Hartley through a Washington maze, suggesting elected officials and former colleagues across government he could meet with. In 2011, she helped Hartley petition the Labor Department to enforce provisions in the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement, a 2005 treaty that compelled the Dominican Republic to follow International Labor Organization regulations on forced labor. Leaked US diplomatic cables from the period of CAFTA’s drafting reported that the agreement “infuriated sugar barons” in the Dominican Republic and singled out Pepe Fanjul for his efforts to “sabotage” it.

It took two years, but in 2013 the Department of Labor released a 42-page report citing Hartley’s petition, which had alleged a wide range of abuses, including “deplorable and unsanitary living conditions” and the denial of medical care and pensions. The government’s report also cited its own interviews with 71 cane workers in documenting evidence of forced and child labor, unsafe working conditions, and inadequate wages. Within six months, ILAB would begin sending monitoring teams to the Dominican Republic.

A boy walks through corn. Many batey residents told us growing food was banned.

A house in Cacata, a “model” batey, where some electricity is available.

Ponticelli was floored. “It was a David-versus-Goliath situation,” she recalled. “He was one person that submitted a petition based on his personal experience. And lo and behold his petition was accepted and the US government took on the obligation to look into those labor violations to point out what needed to be done.”

Following the initial report, monitoring teams continued to travel to interview cañeros without the presence of company bosses. By 2018, the Department reported the Dominican Republic had made “positive steps towards addressing” some labor issues, but noted that “efforts and progress, however, continue to vary significantly across companies.” I asked ILAB for more details, but it has consistently declined to identify potential offenders. Hartley, once thrilled with the Labor Department’s stance, has grown skeptical.

“They have videos, photographs, interviews. If the members of the Department of Labor who have regularly gone down to the plantations of the Fanjul family had the freedom to speak out and say what their eyes have seen,” Hartley told me, it wouldn’t be necessary to get comment from human rights advocates like him.

“If people could see at what price they put sugar in their coffee every morning, they would be absolutely horrified at the living and working conditions of thousands and thousands of men, women, and children. It is horrendous to think that the blood, sweat, and tears of Haitian migrant workers have been slaving away for generations,” he says, “so that we could put sugar on our table.”

Workers preparing Central Romana’s fields for the upcoming sugar crop.

Stove making.

On November 19, 2018, Raoul Hervil, an herbicide fumigator for Central Romana, was spraying chemicals on sugarcane crops when he began feeling light-headed. He was breathing heavily. Raoul, a slight man with warm brown eyes in an angular face, eventually fell to the ground, gasping. Co-workers rushed him to the hospital. It would be his last day working sugarcane for Central Romana.

Twenty years earlier, Raoul had left the eroded lands of Gressier, on Port-au-Prince Bay, along Haiti’s northern coast, to seek work in the Dominican Republic. He landed in Central Romana fields near the eastern edge of the island. Raoul got married and raised four kids on a few dollars a day, eventually settling in a rickety green wooden shack in Central Romana’s Batey 80. That’s where Euclides and I met him, as young men just back from the fields played a game of pickup baseball in the dirt streets behind us.

Raoul started spraying herbicides for Central Romana the year before his collapse. He says they made him feel sick with headaches, flu, fever, and rashes all over his body—a range of symptoms all of the nearly 30 other fumigators we spoke with reported suffering at least in part. But for months, he continued working. “The product cause me a lot of damage,” Raoul says, incessantly scratching his knees and legs as we sat on stools outside his home. “I feel bad the whole day long.”

Medical records show that while Raoul worked as a fumigator, he had already been diagnosed with tuberculosis and HIV. It isn’t clear whether Central Romana supervisors knew about his illnesses or his complaints about the spray; the company did not respond to our queries about what it knew of Raoul’s condition. In a corporate history, the company claims it treats “sugarcane cutters and their families with respect,” providing them “health care and medical coverage at no charge.” Despite this, Central Romana doctors failed to examine Raoul, and he wasn’t taken to Central Romana’s state-of-the-art hospital. (Casa de Campo guests who fall ill are promised “priority attention” at the facility.)

Raoul was surviving thanks to the generosity of his impoverished neighbors and occasional payments for hauling trash. We asked him if Central Romana had provided any money to help with his health. He laughed bitterly. “Never!” he says. “They never give me anything.”

Most of the Central Romana fumigators we interviewed described working with inadequate, broken, or missing protective equipment. “Many times, I go an entire week without a mask,” Raoul’s neighbor, a fellow fumigator, told us, showing us a large, oozing rash around his mouth, which he attributed to chemical exposure. “They always say, ‘Tomorrow we’ll bring you a new one.’ But tomorrow they don’t bring anything. Or there will be holes in the coveralls. Again they say, ‘Tomorrow. Tomorrow we’re going to bring the new one,’ and they don’t.”

Forty-one Central Romana fumigators are part of litigation brought by Robert Vance, a Philadelphia-based plaintiff’s attorney with experience using US courts to get settlements for people in the Dominican Republic harmed by US companies.

One afternoon when Euclides and I were working in the bateyes, Vance and his legal team arrived in Guaymate, a town beyond the reach of Central Romana security. After piling out of a line of SUVs and setting up a makeshift office under a portico in the town square, they took additional statements from fumigators.

Vance has filed in Tennessee federal court, where pesticide manufacturer Drexel is based, as well as in Pennsylvania, alleging “reckless disregard” in exposing the workers to damaging chemicals “motivated by simple greed.” In 1997, the Environmental Protection Agency determined that one compound the company has sold to Central Romana, diuron, likely causes cancer. His motions cite science indicating Drexel’s pesticides pose risks of allergic reaction and damage to the lungs, brain, and digestive tract, while cataloging workers’ complaints of “nausea, abdominal cramps, vomiting, diarrhea,” and breathing difficulties. Many of these symptoms parallel what fumigators reported to Euclides and me.

Another Vance lawsuit filed in a Florida federal court targets the Fanjuls over the eviction of workers from one batey. “Fanjul Corporation is directly responsible for housing conditions of the bateyes, from where the cañeros and the fumigadores live to the use of the pesticides,” Vance told me. “They have never been really required to do what is ethically and morally right by their employees because no one has forced them.”

Raoul might have been in line for payments from Vance’s lawsuits, should they ever come. But his own lung issues proved too much. This June, when Euclides and I returned to Batey 80, a group of four young women sharing a wooden bench gave us the news: Sometime near the end of December 2020, Raoul Hervil died of respiratory failure in his shack. He was 50 years old.

They agreed to show us Raoul’s grave. We drove a few minutes to the Guaymate graveyard, where one of them, Mélida, pointed to a bare wooden stake, painted white, which she recognized only by its alignment with a crack in the cemetery wall. “It’s a shame, a man like Raoul who worked many years in sugarcane,” she said. “Just buried in the dirt. No cross. This makes me very sad.”

When I first came to the Dominican Republic 30 years ago evidence of forced labor in the sugar harvest was glaringly obvious: Men with shotguns guarded locked gates to trap workers in the cane fields. But the International Labor Organization’s indicators of forced labor include more subtle abuses like the hazardous working conditions, low pay, and other issues cane workers regularly describe today.

“We’re talking about coercive forces that are psychological, coercive forces that are driven by debt,” said Duncan Jepson, managing director of the international anti-trafficking group Liberty Shared. “And that’s slightly more subtle than methods of violence.”

One Sunday morning, Euclides and I went to a batey for an Evangelical church service, under a patchwork of red and blue tarps affixed to wooden poles. We’d been invited by a couple I’ll call Efrain and Noni. Noni paced back and forth before the congregation, microphone in her hand, leaning back, giving it everything.

In contrast to his wife, Efrain sat quietly in a folding chair. He’s a “mixer,” part of a team of fumigators who sometimes use sticks ripped from trees to stir chemicals in open 55-gallon drums. Despite Central Romana’s promises to provide health care to workers, Efrain told us he has to pay for much of it himself, which has pushed him into spiraling debt. Together with expenses caused by his brother’s thrombosis, he now owes 30,000 pesos—about $600, or nearly three months’ pay. The lender charges 10 percent per week, Efrain explains: “If you borrow 1,000 pesos, you have to give this person 100 pesos per week in interest.” Yearly, that adds up to 520 percent interest.

More than two dozen cane workers told us their salaries are so low that they’ve turned to money lenders in nearby towns. A municipal firefighter who has a side business making loans to cane workers explained that while Central Romana doesn’t operate the loan shark rings, the company’s low wages leave workers desperate and willing to pay exorbitant rates. One of the ILO’s elements of forced labor is “fraudulent debt from which workers cannot escape.”

It’s a brutal cycle, Efrain tells us. The canecutters are in debt until they die.

Myrthos Pierre Louis says Central Romana paid him a year’s wages after a sugarcane cart accident cost him the use of his legs, but nothing since.

Sugar is not the only thing that’s made the Fanjuls so rich. Their profits are sweetened thanks to the politics of the United States. Not only does Central Romana benefit from a tariff program under which the Dominican Republic gets a greater share than any other sugar-exporting nation—with the company filling nearly two-thirds of that quota—but it also profits from a congressionally authorized federal price-support program that inflates the value of each pound by about 10 cents. Vincent Smith, an agricultural economist and critic of the program, estimates the Fanjul family is “getting at least $150 million a year” in net benefits from the program, with another $25 million going to Central Romana’s imports. “That’s a very substantial concentration of benefits on a very small number of folks,” Smith says.

Some of that money goes back to seed the American political system. Over the last 20 years, Big Sugar has spent more than $220 million on campaign contributions and lobbying to sustain the price-supports and oppose stricter dietary guidelines, with 40 percent of that, according to OpenSecrets, coming from Fanjul-affiliated companies and lobbying groups. Smith, citing Federal Election Commission data, points out that the Fanjul empire and allied sugar organizations spend 10 million every year on lobbying and campaign contributions. “They’re not doing this out of the goodness of their hearts,” says Sheila Krumholz, OpenSecrets’ executive director. “It’s a very good investment.”

Alfonso Fanjul, Judith Giuliani, Rudy Giuliani, and Raysa Fanjul at a charity ball in 2017.

Nick Mele/Patrick McMullan/Getty

The Fanjuls are famous for giving across the aisle, a habit that has helped protect their government payouts no matter which party holds the upper hand. Alfy aligns with the Democrats; Pepe with the GOP. Trump’s billionaire Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross and his wife have been guests at the Fanjuls’ Casa de Campo mansion. “The Fanjuls are the most delightful hosts,” Hilary Geary Ross said of Pepe and Emilia Fanjul in the society column she wrote for a Palm Beach magazine. The top recipient of Fanjul largesse serving today—with more than $280,000 across his Senate career—is Florida’s Marco Rubio, a key supporter of the price-support program. In his memoir, An American Son, Rubio describes his close relationship with the Fanjuls, including a dinner hosted on their boat, and a “Labor Day weekend in the Hamptons, where many of their friends and major Republican donors would spend the holiday.”

Alfy Fanjul moves among powerful Democrats, historically, none more than the Clintons, who have spent time at Casa de Campo, where Bill golfed. Perhaps the most famous example of the Fanjuls’ access to power was captured in the Starr report: Alfy Fanjul, upset over Vice President Al Gore’s presidential campaign pledge to tax sugar producers a penny per pound to preserve the Everglades, reached Bill Clinton by phone in the Oval Office as he made a failed attempt to end his relationship with Monica Lewinsky. In a written statement, a Labor Department spokesperson insisted that the Fanjuls’ political power has not shaped its actions: “DOL has not modified its position on the Dominican Republic as a result of any public or private actors attempting to influence it.”

A woman selling charcoal, which is widely used in the unnelectrified battles.

Pedro Farias-Nardi

A local Dominican merchant visits a batey with plantains.

Forced labor in other global agricultural supply chains is coming under growing scrutiny. Countries exporting cotton, seafood, and palm oil have all been subject to bans from US Customs and Border Protection under a 1930s law that blocks importing goods produced by forced labor.

“This isn’t like sex trafficking, for instance, where the business is completely criminal and illicit,” said Jepson, who successful fought to block the United States from importing palm oil made by one of the world’s biggest producers. “These are businesses that are publicly listed, perhaps listed in multiple stock exchanges.”

In recent years, Mars and Hershey have adopted extensive policies on sustainability and human rights, particularly around cocoa and palm oil. While they say little about sugar, advocates focused on the cane workers are fighting to change that. Last year, activists and clergy caught wind that Central Romana was applying for membership in a trade organization, Bonsucro, that includes plantations and end users like Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, General Mills, Mars, and Hershey, and which has developed a rigorous code governing environmental and employer conduct. They sent letters and documentation of the company’s record to Bonsucro leadership, urging them to deny the application. “For many years we have faced a strong problem of human rights violations against Dominican and Haitian families by Central Romana,” wrote Miguel Ángel Gullón, a member of Dominicans for Justice and Peace, in a February 2020 letter that urged a “profound rejection” of the company. Two months later, Bonsucro turned Central Romana down, citing allegations that, “if proven, could put Central Romana in breach” of Bonsucro’s code of conduct. Today, the company touts certification from an alternative group called ProTerra.

Central Romana seems to have no difficulty finding customers. Nearly 1 in 7 tons of raw sugar arriving at the Baltimore facility of American Sugar Refining—the Fanjul corporation that owns Domino, C&H, and other processors—originates in the La Romana port. Hershey, whose iconic chocolate factories are only about 90 miles from the Baltimore refinery, is one of many companies that sources sugar there. After summarizing our findings documenting the workers’ conditions and following up with more than a dozen emails and calls, the chocolate-maker declined our requests for an interview and issued a general statement saying the company wouldn’t tolerate forced labor or unsafe conditions. But companies can’t deny where their supplies come from. Traceability reports allow end users to determine the origins of the sugar they buy. Nor is there doubt that Central Romana’s sugar is made by men like Julio and Cardenas, working up to their 80s for $3 a ton; like Noni and Efrain, sick and stuck in spiraling debt; like Raoul, whose body lies under a stick in the cemetery near Batey 80.

On the map, the “Carretera Internacional” appears to wind back and forth between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, providing a supposed shortcut to our destination: Batey 8, once a state-run sugar plantation in the Barahona province. In truth, it’s a nearly impassable dirt road with deep ruts that kept our average speed around 10 miles an hour.

We wove between the two nations: On our left, lush, sloping grassy washes of the Dominican Republic, not a building or person in sight. On the right, the fallen hillsides of Haiti, badly eroded, nearly devoid of trees, where families waved as we passed. This was the territory many Haitians left behind to work on the Dominican Republic’s sugar plantations. In recent years, they come voluntarily, out of desperation. Not long ago, many, like Lulu Pierre, essentially had been sold into bondage.

The road’s end brought pavement as smooth as glass. We zipped along, arriving as night fell. Go see the oldest man in the batey, someone told us, pointing behind a low brown row house. If anyone knows what happened to Lulu, it would be him.

Soft laughter mixed with crickets. Merengue wafted from radios. Here, on a concrete porch in a red plastic chair, we found an 85-year-old man named Rene. Euclides and I pulled up a couple of cement blocks to sit and tell our story. He listened, then said without pause, “Yes. I remember Lulu Pierre.”

Rene confirmed that Lulu was a victim of a human trafficking operation run by buscones for the Dominican state sugar council, aided by Dominican military. He recalled how Lulu, like many others, arrived from a clandestine border crossing in the dead of night, on a bus stuffed with 60-some Haitians. Some were tricked, he said—“told they were going to make a lot of money here”—and others kidnapped.

Until now, my search for Lulu had nearly gone dry. Birth registry officials in Haiti had even convinced us that Lulu wasn’t his given name. Despite all that, I now sat face to face with an old man ready to answer questions I’d been asking nearly half my life. What happened to the child? Did those long-ago efforts to help Lulu escape make a difference?

Rene said they had. A Catholic clergy member, Brother Leon Delaney, had escorted Lulu back to the border town of Jimani. From there, Rene was certain, Lulu made it back home.

We were silent, letting the moment sink in. It was nice to think that Lulu had an emotional reunion with his family. Euclides even imagined a feast of goat meat, French beans, and white rice to celebrate his return. But the story brought us only modest comfort. For by now, we carried the tales of Efrain, Noni, Raoul, and many other cañeros who make sugar to sweeten American coffee and candy. Lulu might have escaped, but what we saw left a bitter taste.

This story was published in partnership with the Center for Investigative Reporting and made possible with support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Additional reporting by Michael Montgomery.