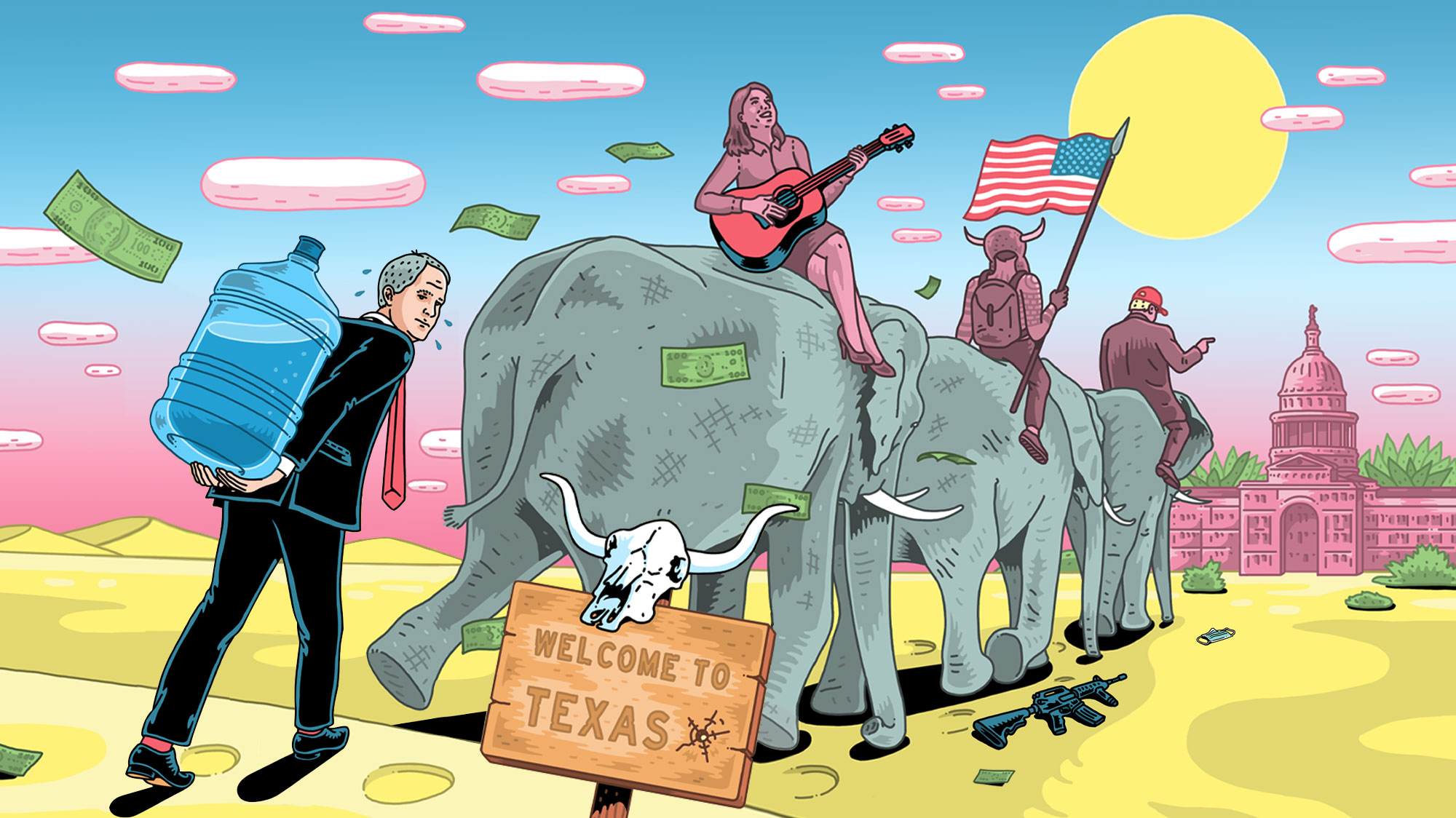

It was hardly the keynote slot—before Donald Trump Jr. and Kimberly Guilfoyle, before Eric and Lara Trump, before Rudy Giuliani calling for “trial by combat,” before John Eastman, dressed for some reason like Indiana Jones, and long before President Donald Trump, who would speak for more than an hour and incite an insurrection against Congress. But Ken Paxton didn’t mind being an afterthought when he took the stage at the “Save America” rally in Washington on the morning of January 6. The Republican attorney general of Texas was happy just to be there at all.

The 58-year-old Paxton wore a thick tartan scarf with a long black coat and no gloves, and his gray hair, stubbornly parted for decades, drifted haphazardly across his forehead in the stiff January wind. When he was 12, Paxton nearly lost his right eye in a freak accident during a game of hide-and-seek. It left permanent damage—it’s a different color from his left one, and the lid above it is half-closed. The effect is that whether he is posing for a mugshot or addressing a large group of people preparing to hang Mike Pence, Paxton’s face appears fixed in a mischievous half-smirk.

But as he stood on the podium that morning, Paxton had good reason to smile. One month earlier, beset by a damning series of allegations from his own staffers of personal and professional wrongdoing, Paxton’s career seemed to be free-falling. Then he found a parachute. Rejecting centuries of constitutional law and democratic traditions, Paxton filed a lawsuit arguing that Pennsylvania and three other states won by Joe Biden had harmed Texas by expanding mail- and early-voting access during the pandemic. He asked the Supreme Court to strip those states of their Biden electors and instruct their legislatures to replace them with new ones, effectively making Trump the victor of the 2020 election. Paxton’s gambit was one level removed, legally speaking, from one of those ransom notes they send in movies with all the letters cut out from magazine headlines. His brief miscalculated the number of electoral votes at play and, citing the calculations of one random man in Berkeley, falsely asserted that “the statistical improbability of Mr. Biden winning the popular vote in these four States collectively is 1 in 1,000,000,000,000,000.” But that did not stop many of the gop’s most prominent figures from endorsing it. A majority of the House Republican conference signed their names to an amicus brief. So did 17 other Republican state attorneys general. Trump truly believed it could work, and Sen. Ted Cruz promised to argue the case before the Supreme Court.

The justices unanimously rejected Paxton’s argument. Only two of them even believed he had standing to make it. In normal circumstances, such a defeat would have been a great embarrassment. But here in front of the White House, looking out on a sea of red hats and flak jackets, Paxton was taking a victory lap. With his wife, Angela, a Republican state senator, standing silently beside him, Paxton sped through his record in the frenzied cadence of a French cinematographer wrapping up at the Oscars. Texas had stayed red when states such as Georgia had flipped, he explained, because he had been willing to “fight” by filing lawsuits to restrict voting. “We kept fighting in Texas,” Paxton said. “We will not quit fighting,” he promised. His speech was over in three minutes. And then, not long after, the crowd made its way to the Capitol and kept fighting there.

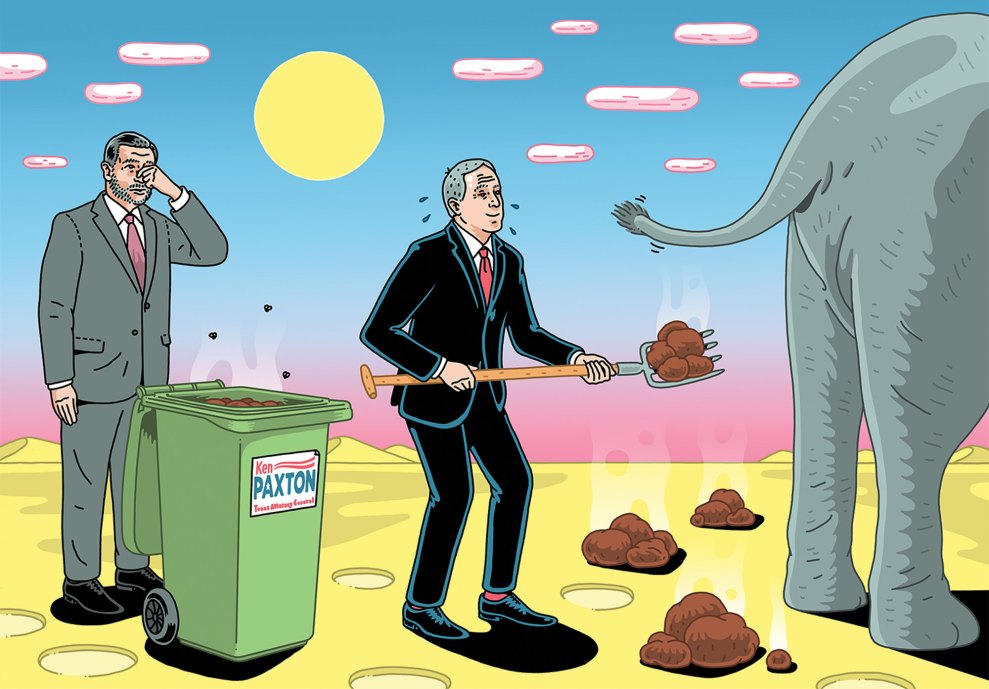

If you put all the component parts of Trump-era conservatism in a fridge and went away for a while, Ken Paxton is what you’d get when you finally opened the door. In a state that’s produced some of the most significant political personalities of the last half-century, Paxton is a mediocre mess. He is not one of the Republican Party’s big thinkers. He has not, like Cruz or Josh Hawley, his partners in the would-be coup, been groomed since his teenage years for the national stage. He has never had to appeal to the unconverted or deviate from what passes for the norm in Texas Republican politics. He has been under indictment for six years. As the crowd at the Ellipse witnessed, he has all the charisma of a writ of certiorari. Even the lawsuit he championed in Washington was borrowed from somebody else. Prior to his election as attorney general, the most notable thing he’d done at a courthouse was filch a $1,000 pen from another lawyer.

But you don’t need to be brilliant or ethical or charming to wield a lot of power in state government; you just need to keep the right people happy for long enough. And Paxton, for all his transgressions, has been a dependable vehicle for reactionary interests, inside and outside his state, for years. He’s led a legal crusade against immigrants, voting rights, environmental regulations, health care access, and trans equality. He’s scuttled local efforts to protect citizens from gun violence and COVID-19. And he’s taking an axe to Roe v. Wade.

Paxton’s persistence in the face of endless scandal makes him a model apparatchik for the current moment. He will never be president, but in a golden age of Republican corruption, in which anyone with ambition must bend the knee to an aspiring autocrat, a warm body with nothing to lose can do a lot of damage. By laundering the theories of conspiracists and hacks, he did as much as anyone short of Trump to make the Big Lie the new party orthodoxy. And in the process, he held a black light up to the rest of the conservative legal movement—the institutions and officials and donors who have turned jobs like his into some of the most powerful in state politics, and the compromises they’ve made to do it. There are a lot of Ken Paxtons out there, it turns out, and they were all just waiting to fall in line.

Like many of Texas’ loudest Republican leaders, Warren Kenneth Paxton Jr. came from somewhere else. The son of a B-52 pilot, Paxton spent his childhood on the move, living with his family in a trailer without air conditioning in six different states in 10 years. Paxton was raised Christian but traces his personal religious awakening to a summer he spent as a teenager at Falls Creek, the city-sized Baptist youth camp in Oklahoma. “I realized as I saw people coming to Christ that I didn’t have what they had,” he said in a 2017 interview with the Christian broadcasting mogul Joni Lamb, whose late husband, Marcus, flew the Paxtons to Trump’s 2017 inauguration.

Teenage Paxton was anxious about committing himself to Christ, fearful that “God would send me somewhere like Africa.” Instead, he ended up in Waco, where he was elected Baylor’s student body president, raised a live bear cub—the school mascot—in his apartment, and met his wife. They soon moved to Charlottesville, where Angela taught public school and Ken studied law at the University of Virginia.

Paxton went to UVA rather than the University of Texas, he later explained, believing he would have to compete with fewer classmates for jobs in Texas after graduation. On a campus that nurtured egos—Fox News host Laura Ingraham was in Paxton’s class—Paxton “wasn’t somebody who would draw attention to himself,” recalls Neil Rowe, a fellow law student who belonged to a small Christian fellowship with the Paxtons and about a dozen other students and spouses. Paxton wasn’t on the law review. He didn’t send letters to the Cavalier Daily. Most of the fellowship’s members were married, and they would meet at each other’s homes once a week to have dinner and play board games, and sometimes chip in to assist fellow law students facing financial difficulties. “He was kind, he was caring—he cared about people who had different needs than we have,” Rowe says. “Every time he opens his mouth, I’m disappointed all over again.”

Paxton’s faith was a natural conduit to politics in North Texas, where the family settled in the mid-1990s—initially, to help plant a church in the small city of Frisco. Ken worked as a lawyer for J.C. Penney. Angela homeschooled their four children, then taught math at a private Christian academy they later sent their own children to. Suburbs like Collin County, north of Dallas, were the launchpad of the Christian conservative takeover in the state, and the Paxtons were deeply involved in the anti-abortion movement that powered it. Ken served on the board of a crisis pregnancy center attached to a megachurch called Prestonwood Baptist (which they eventually joined); Angela, deeply influenced by her own adoption, has worked with an organization that sells upscale clothing and uses the proceeds to pay for sonograms.

Angela, everyone who has met both of them seems to agree, is the family member with the more evident political talent. But Ken is a common denominator, a white man in institutions made for them, carried along on the current of conservative politics and privilege. He once said that the key to his political success is that he has a three-syllable name. So when Angela told him one morning in 2001 that she’d had a dream that he would run for office, it was only a matter of time before Ken acquiesced.

“I don’t know what happens when you ask God for an answer and you don’t do it,” he explained later, “but I don’t want to find out.”

Paxton was an unremarkable legislator in his first half-decade in Austin—a backbencher whose highest-profile stunt was a law adding President George W. Bush’s name to “Welcome to Texas” signs. But while Paxton’s political career was idling, his business career was never busier.

In Texas, where the legislature convenes for a few months every two years, members often keep whatever jobs they hold in private life. This leaves the chamber rife with conflicts of interest. The legislature’s ethical guidelines, says Andrew Wheat, research director at Texans for Public Justice, a nonprofit that has filed numerous complaints against Paxton over the years, are “basically a joke.” It is a perfect place for a lawmaker with few scruples to leverage new connections.

When Paxton took office in 2003, his financial disclosure listed just one venture, a small law firm specializing in estate planning. By 2014, the Dallas Morning News revealed, Paxton was involved in 26 businesses. There was a real estate scheme with his local district attorney, which netted $1 million by flipping property to the county. Paxton was a major investor in a startup that produced dashcams—and then voted for a law making them mandatory for cops. People who stopped by Paxton’s law office for some estate planning might come away with a referral to a donor’s investment firm—which, unbeknownst to them, was paying Paxton a commission.

Paxton had a nose for business ideas, but they were not always good ones. Take Pirin Electric. In that case, he and three other Republican state representatives were part of a group of investors who lost $2.5 million to a Prestonwood member who had become a local celebrity after claiming to have found the possible remains of Noah’s Ark in Iran. The scheme, which involved speculating in the state’s deregulated utility market, offered a window into Paxton’s world—a tight network of suburban white men, linked closely by politics and faith, playing a little too fast with money. As one Collin County resident who was a member of the Rotary Club with Paxton during this time told me, “Jesus is involved in every deal.”

Then, in 2010, Republicans took huge majorities in the legislature, powered by tea party–fueled margins in North Texas. But the speaker of the House was Joe Straus, a moderate Republican (and to the consternation of some, a Jew) who had cut a deal with Democrats to land the job. Paxton, reading the winds, decided to challenge him. It was never much of a contest, but he won by losing. By the time the crowded 2014 primary for attorney general rolled around, the resources of the party’s anti-Straus right, including the National Rifle Association and anti-abortion groups such as Texas Right to Life, were at his disposal. Empower Texans, a PAC funded by the billionaire oilman Tim Dunn, who has spent huge sums waging an intraparty civil war on behalf of Texas conservatives, guaranteed a million-dollar loan to Paxton’s campaign during the primary. The campaign blanketed the airwaves with clips of Cruz hailing him as a defender of “religious liberty.”

A primary opponent dug up a lawsuit from a couple alleging that Paxton, after being hired to prepare a postnuptial agreement, had pushed them to make a bad investment with a financial manager he was friends with—without revealing he’d get a commission. The couple dropped the suit, but a few years later Paxton was caught acting as an unregistered securities broker again. Paxton admitted to wrongdoing and paid a small fine to the state securities regulator. His opponent in the primary runoff—a Straus ally—talked up the story, to no avail. In November the party closed ranks around Paxton. The job was just too important to fall into the wrong hands.

During the Obama years, state attorneys general took on an exalted status on the right, as checks against the scary federal government in Washington. Measured in campaign dollars, the growth was practically vertical. The Republican Attorneys General Association, formed in the 1990s by lawyers who believed the landmark tobacco settlements could have a chilling effect on big business, raised less than half a million dollars for its campaigns in 2002. In 2014, when Paxton won, it hauled in $16 million. Four years later, it raised more than double that.

Those investments stemmed from a growing recognition among corporate donors and strategists of the vital role state AGs could play in a broader national agenda—a bridge between the right-wing takeover of the courts and the increasingly reactionary and gerrymandered state governments. Republican AGs filed 56 multistate lawsuits against the Obama administration, according to Paul Nolette, a professor of political science at Marquette University, winning major victories on everything from immigration to health care to environmental regulation. And Texas led the way. Gov. Greg Abbott, Paxton’s predecessor as attorney general—and Cruz’s boss in that role—once described his job in three steps: “I go into the office in the morning, I sue Barack Obama, and then I go home.”

Paxton promised more of the same. But seven months into his term, a Collin County grand jury indicted him—on two counts of securities fraud and one count of acting as an unregistered securities broker. Not long after, the US Securities and Exchange Commission brought charges of its own. This time, it was a company called Servergy, which Paxton had pitched to his friends as a can’t-miss opportunity, that landed him in trouble. Its signature product, a purportedly game-changing server for data centers, was nothing of the sort, and a much-hyped deal with Amazon didn’t exist. A former Republican state representative named Byron Cook blew the whistle. Cook had been Paxton’s roommate for a time in Austin, and they’d done deals together before, including the dashcam business. Paxton had persuaded Cook and other acquaintances to sink a combined $840,000 into the venture. What Cook didn’t realize was that Paxton had not purchased any shares in the company himself. Over lunch at a Dairy Queen, the company’s founder had instead offered him a stake in the company as a “gift”—which prosecutors alleged was compensation for bringing others on board. “God doesn’t want me to take your money,” the company’s founder told him.

From the moment the indictments dropped, Paxton’s tenure in office was consumed by a desire to survive what he called—in a glimpse of the world to come—a “witch hunt.” While Paxton’s staff held down the fort in Austin and supporters financed an ad blitz denouncing the prosecution, “the general” (as he prefers to be called) was increasingly holed up at home. Paxton portrayed himself as a persecuted Christian, beset by the forces of darkness.

“I could immediately feel it the day I stepped in,” he told Joni Lamb, the Christian broadcaster. He was engaged in a “spiritual battle.”

Paxton circumvented anti-bribery statutes by accepting large sums of money from “family friends” and “former clients” for a legal defense fund, including $100,000 from the CEO of a company that was under investigation by the AG’s office and the Department of Justice for Medicaid fraud. (The company eventually settled, with no admission of wrongdoing.) At the same time, his allies moved to defund the prosecution. Taking advantage of a new Texas law that moved public-integrity prosecutions out of Austin and onto elected officials’ home turf, a Paxton campaign donor named Jeff Blackard sued the all-Republican Collin County commission, alleging that the cost of a trial would be an imposition on taxpayers like himself.

At a commissioners’ meeting in 2017, one Paxton supporter after another stood up to attack the case. The lawyers going after Paxton, said one, were as sleazy as O.J. Simpson’s. “Jesus Christ,” said another, “would not want to see a man like General Paxton, who had done no harm and no wrong, prosecuted.” The speakers included Blackard and his wife (who told the commissioners she had partied with the Paxtons the previous week at Trump’s inaugural) and a former Paxton staffer. The tactic worked—the commissioners voted to cut off funds for the case, and special prosecutors have now spent years fighting to overturn the decision in court. Two more Paxton friends—the trustee of his blind trust and a pastor at Prestonwood—are suing Cook and another witness for allegedly defrauding them in a land deal. (Paxton had been both a manager and a lawyer for the company involved in the venture; even the efforts to exonerate Paxton dragged him into the mud.)

Paxton has scored one major blow already. The federal charges were dismissed in 2017 on the grounds that he never explicitly told his friends he was buying shares, and he did not actually know that his claims about Servergy were false. (A judge eventually ordered Servergy’s former ceo to pay a $22,500 fine for having “negligently violated” securities law.) But the county case is different—Paxton has already admitted in writing to acting as an unregistered broker. It is hard to keep track of where that case even stands at this point, and that, as much as winning, is sort of the point—the docket is so impenetrable, the delays a result of so many intervenors and appeals, that it allows Paxton to present himself as the real victim. He just wants a speedy trial, Paxton insists. Isn’t this America?

When Paxton was first indicted, his days in Austin seemed numbered. But in 2018, Republicans dragged Paxton’s limp campaign to victory again, by the narrowest margin of any statewide elected official. Groups including Texas Right to Life and the state’s Fraternal Order of Police threw their support behind him. So did Texans for Lawsuit Reform, a corporate-backed kingmaker that had helped cement Republican control of the state in an unending push for tort reform.

For all the turmoil, Paxton’s office was giving these varied conservative constituencies their money’s worth. Over the last decade, Texas politics has revolved around increasingly severe anti-abortion rules and legislation. And Paxton, a product of the anti-abortion movement, delivered for those activists in office, harassing abortion providers such as Planned Parenthood and defending the state’s crackdown on reproductive rights in federal courts. He sued to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (which conferred some protections on undocumented immigrants who had come to the United States as children), led a push to kill the Affordable Care Act, and moved to gut the Obama administration’s anti-smog rules. After the US Supreme Court ruled in 2015 that same-sex marriage bans violated the Constitution’s equal protection clause, Paxton told Texas judges to ignore the ruling. Angela, who would soon win election to the state Senate, sometimes appeared at rallies on the attorney general’s behalf, strumming an acoustic guitar and crooning a country twist on Abbott’s mantra: “I’m a pistol-packin’ mama, and my husband sues Obama.”

Jason Ravnsborg (S.D.)

After killing 55-year-old Joseph Boever with his car in 2020, Ravnsborg told police he kept driving because he thought he hit a deer. Police found the victim’s glasses on Ravnsborg’s front seat the next day. He pleaded no contest to two misdemeanor traffic charges and paid minor fines. And yes, he kept his driver’s license.

Leslie Rutledge (Ark.)

Rutledge also teamed up with Paxton to challenge the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan, the Biden administration’s prohibition on LGBTQ workplace discrimination, and DACA. She helped draft legislation barring transgender high school athletes from competing in girls’ sports and, in August, published an official opinion stating that the teaching of “antiracism” violates the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Eric Schmitt (Mo.)

He has sued China for allegedly causing the Covid-19 pandemic, school districts for imposing mask mandates, and the city of St. Louis for limiting the size of indoor gatherings. Like his predecessor, Josh Hawley, Schmitt isn’t planning on staying in the job long—he’s running for Sen. Roy Blunt’s soon-to-be-vacated seat.

Ashley Moody (Fla.)

After the insurrection, Moody scrubbed her bio of her past affiliation with the Rule of Law Defense Fund, the group whose robocalls urged Trump supporters to “march to the Capitol building…to stop the steal.” Her efforts to undermine the democratic process run deeper still. When Florida passed a law forcing people with felony convictions to pay off court fees before being able to vote, Michael Bloomberg volunteered to pick up the tab. Moody reported him to the FBI, claiming it might be a form of vote-buying.

Derek Schmidt (Kan.)

In 2012, as a member of his state’s elections board, he and his

birther colleagues questioned Obama’s eligibility to appear on the ballot. A candidate for governor in 2022, Schmidt fiercely opposes reproductive rights. In July, after a court struck down a referendum banning abortions in the second trimester, Schmidt accused the judges of trying to “defeat democracy.”

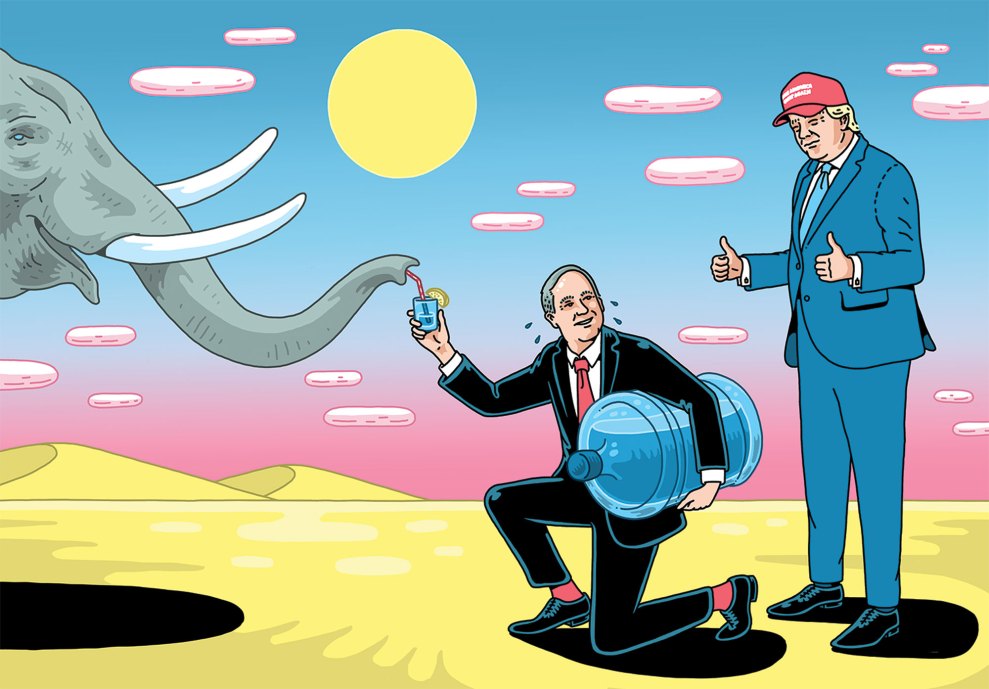

By 2020, with his case no closer to resolution, Paxton was being feted at the Federalist Society as a “defender of the bulwarks of federalism” and had served as chair of the Republican Attorneys General Association. Texas was once more at the vanguard of the nation’s conservative movement. And in the sitting Republican president, Paxton had a worthy ally—two men of dubious motives who had something to gain from the other.

With Texas emerging as a battleground in the November presidential election, Paxton challenged efforts in large Democratic-leaning counties to expand voting access, while zealously prosecuting even the most minor cases of voter fraud. Although a Houston Chronicle analysis found that more than 22,000 hours of investigative work by Paxton’s office had netted just 16 cases in 2020, the outcomes of those prosecutions mattered less than the story that national Republicans wanted to tell: The election must be secured so it could not be “stolen.”

On September 24, Paxton triumphantly announced the indictment of a commissioner in a small East Texas county for alleged absentee ballot fraud in a local Democratic primary election. It was proof, he said, that “mail ballots are vulnerable to diversion, coercion, and influence by organized vote harvesting schemes.” One week later, seven Paxton staffers—including some of his top subordinates—left the office after an early lunch and reported their boss to the FBI.

The staffers later texted Paxton, informing him they had “made a good faith report of violations of the law by you” and demanding a meeting with him. Paxton declined. Instead, in the days and weeks that followed, he fired or forced out each of those staffers, and a scandal simmering behind the scenes for months boiled over into public view.

In the formal complaint the whistleblowers filed with the FBI, and in a subsequent lawsuit for wrongful termination brought by four of them, Paxton’s staffers detailed a “bizarre” pattern of behavior from their boss on behalf of an Austin real estate developer named Nate Paul, “with whom the Attorney General has formed a strong personal bond, and with whom the Attorney General increasingly spends large portions of his free time.”

Paul, whose properties ranged from a collection of parking garages to a downtown bikini bar, was the kind of figure many politicians—to say nothing of an attorney general—would have kept at arm’s length. More than a dozen businesses associated with his real estate empire have gone bankrupt in recent years, and the FBI had raided his home and offices in 2019 as part of an unspecified investigation. But during the summer of 2020, the whistleblowers alleged, Paxton had gone to extraordinary lengths to help his friend. The AG had intervened in a lawsuit between Paul and a charity he owed money to. When some of Paul’s foreclosed properties were set to be auctioned, Paxton’s office issued a last-minute opinion stating that such auctions must be suspended during the pandemic. That in itself was suspicious; he has sued to block virtually any institution that attempts to take proactive steps to reduce COVID-19 transmission.

Most glaringly, in the eyes of his aides, Paxton had hired a special prosecutor to investigate Paul’s claims that various state and federal officials were engaged in a criminal conspiracy against him. (In October, Paul sued the state and federal agents investigating him, alleging that the raids had violated his civil rights and damaged his reputation.) That move alarmed staffers, who believed the hiring might have been illegal. Citing Paxton’s “frantic” and “obsessive” activity, his penchant for cycling through personal “burner” phones, and his closeness with Paul, they feared that Paxton was performing his duties “under duress.” In the wrongful termination lawsuit, they speculated that the moves might have been “an effort to repay Paul” for a $25,000 donation to Paxton’s reelection campaign. Their most intriguing theory was one that cut at the core of the Paxtons’ power-couple brand: Sometime in 2019 or 2020, they stated, Paxton had admitted that he’d had an extramarital affair with a former aide to a Republican state senator—and Paul had subsequently given the aide a job. (In a deposition in late 2020 as part of the ongoing litigation with the charity, Paul confirmed that Paxton had recommended the woman.) The whistleblowers “reasonably concluded,” they stated in their lawsuit, that Paxton’s desperate need to cover up the alleged affair might explain his behavior. Paxton, who speaks almost exclusively to conservative TV and radio hosts, has managed to avoid answering any questions about the alleged affair for more than a year. But in a statement immediately following the complaint, he accused the staffers of making “false claims.” Eventually, his office released a report exonerating him of any wrongdoing.

The whistleblowers were no deep-state moles. One had even been denied a federal judgeship after reporters dug up a speech in which he called transgender kids “Satan’s plan.” They had eagerly signed up to work for the flagship of reactionary federalism; instead, they worried they had become Paxton’s accomplices.

The criminal complaint—followed by the confirmation that the FBI was now poking around—cracked the dam that had prevented Paxton’s previous foibles from swamping his political career. Some Texas Republicans, including Rep. Chip Roy, a former Paxton deputy, called for him to resign. Allies in Collin County began to inch away.

But in the Trump era, with its obsession over deep-state corruption and witch hunts, this latest scandal came with a built-in language of rationalization for Paxton to tap into. Emboldened by Trump, scandal-plagued sycophants paraded their legal problems the way candidates once touted endorsements. Grave allegations of wrongdoing became almost a shield against consequences—proof, in fact, that you must be doing something right. So Paxton kept going. Having already been accused once of selling out his office to a real estate developer with a history of bankruptcies, Paxton decided simply to do it again on a bigger stage.

The November election offered Paxton a shot at redemption. As soon as the results were in, Paxton embarked on a media tour to plant doubts about the outcome, hinting that Texas had detected something off about Dominion’s voting machines and amplifying false allegations of a vast conspiracy in key swing states. A succession of lawsuits from the Trump campaign were laughed out of court, and the RNC’s own counsel privately called their arguments a “joke.” But the post-election landscape was shaped by the increasingly perverse incentives of Republican politics: The fact that there was no legal basis for such claims made it even more imperative that someone with power make those claims. On December 8, less than a week before the Electoral College would meet, Paxton, on behalf of the state of Texas, sued Pennsylvania and three other swing states that had gone for Biden, calling for their results to be thrown out.

“It’s hard to understand just how radical and frankly insane the lawsuit was,” says Steve Vladeck, a professor of constitutional law at the University of Texas at Austin.

Paxton’s arguments had already been rejected in other courts. He produced no evidence of fraud, and he recycled absurdities. But beyond the slapstick lawyering, the willful disregard for the constitutional order portended something ominous. It was a post-legal document—less a sincere constitutional argument than a coup threat in legalese. Paxton was not just providing cover to a desperate president; he was driving the conservative legal apparatus into new territory and setting the stage for the next election challenge to come.

Here, again, Paxton was a vessel of convenience—someone willing to cross a line so others might follow. As the New York Times later reported, the lawsuit had first been distributed by Michael Farris, a homeschooling activist and president of the Arizona-based Alliance Defending Freedom. Texas embraced it after South Carolina balked. (Paxton did make some changes—for instance, his lawyers inserted the embarrassing “one-in-a-quadrillion” claim.) When staffers in the Florida attorney general’s office first saw Paxton’s brief, they began emailing frantically back and forth. The argument was “batshit,” one attorney wrote in an email, noting that Paxton’s own solicitor general did not sign his name to the document. “Perhaps this is Paxton’s request for a pardon,” speculated another. But Paxton was trading legal credibility for political cover. After Trump hailed the suit as “the big one,” South Carolina, Florida, and 15 other states eventually signed on. Paxton dashed off to Washington to meet with Trump to discuss what his schedule cryptically referred to as “state–federal matters.”

Reporters asked Paxton the obvious question: Did he discuss a pardon with Trump? “I’ve had no discussions with anything about…anything like that,” Paxton said, although the White House later confirmed that Paxton had lobbied the president to grant clemency to a major donor to his legal defense fund, who had previously pleaded guilty to tax evasion.

When the Supreme Court unanimously rejected Paxton’s case the next day, he was at the White House Christmas party. And in the weeks that followed, as Trump pursued every avenue to thwart the certification of the election results and the peaceful transfer of power, Paxton was one of his most eager allies. By the morning of January 6, Paxton was back in DC. The visit was purportedly official business, although his office won’t say who paid for his flights and hotel, nor will it release any communications from his time there, claiming that every email and text he sent in DC was covered by “attorney-client privilege,” even though it’s not really clear what the “client” or “case” could be. (The congressional committee investigating the insurrection has subpoenaed these records.) His schedule called for an appearance on the Mall, followed by an afternoon and evening of media hits—and another visit to the White House the next morning.

In December, days after Paxton filed his election lawsuit, Kevin Moran, a retired journalist and Democratic activist in Galveston, dashed off a complaint to the State Bar of Texas. Paxton’s case was not only a fool’s errand, he argued; it was malpractice on Texans’ behalf. Dozens more complaints followed. In June, in an unprecedented gesture, a coalition of former bar presidents and officers lodged their own complaint. Paxton’s election lawsuit is now the focus of a formal bar investigation.

Paxton has defended himself against the probes by arguing that it is unconstitutional to lodge a bar complaint against the attorney general. This is a familiar Paxton tactic: His lawyers in the securities case argued that the entire securities-registration law was unconstitutional. He defended himself against the whistleblower complaint by arguing that the whistleblower law does not apply to him, because the attorney general is not a public employee. (An appeals court disagreed.) A public official is traditionally held to a higher standard than a private person. Paxton contends that he should actually be held to a lower one, acting as a sort of anti-lawyer, entirely unconstrained by institutions and traditions. It is the state-level analog to the position Trump’s lawyers took in his impeachment trials: If an attorney general does it, it must be legal.

Given the various cases against him, Paxton might not keep his job much longer. Texans for Lawsuit Reform—Paxton’s top donor over the course of his career, to the tune of $1.4 million—is calling for a replacement. “The Texas Attorney General’s Office is too important to operate under a cloud of suspicion and without adequate legal talent to represent the best interests of Texans,” the group’s spokesperson, Lucy Nashed, said in a statement. Three serious primary challengers are already running against him, most notably George P. Bush, the state land commissioner and nephew of President George W. Bush. Some of Paxton’s other donors are beginning to defect, and a number of powerful conservative groups, such as the National Border Patrol Council, have thrown their support behind the state’s most famous Republican heir. In August, George P. Bush visited Prestonwood Baptist Church—posing for photos with Paxton’s own pastor. These Republican opponents present themselves as Paxton without the baggage.

In November, Paxton’s team was back at the Supreme Court for another big case—a defense of the state’s abortion law, which bans procedures before many women even know they’re pregnant. The wrinkle was that ordinary citizens, rather than the state, would take responsibility for enforcing it, by suing anyone who so much as drove an ineligible woman to a clinic. Like the election lawsuit before it, the law was a radical and cynical gambit attempting to exploit cracks in the existing constitutional framework. His office argued that the ban was “stimulating” interstate commerce by compelling patients to travel to Oklahoma. Once again, despite others’ initial misgivings, it wasn’t long before many in his party fell in line. And this case wasn’t going to be laughed out of court—in December, the Supreme Court ruled that the law could stay on the books while legal challenges from abortion providers move forward.

When I spoke with Cecile Richards, the former president of Planned Parenthood who is now co-chair of the Democratic super-pac American Bridge, she pushed back on the idea that Paxton was an “outlier” who could be separated from his peers so easily. In defending the abortion law, after all, he was once more carrying water for his colleagues. “It’s not just about Ken Paxton,” she told me. “How could someone this corrupt, this incompetent, this unengaged, and with such extreme politics, continue to get elected in the state of Texas? That really goes back to the complete control of the Republican Party by the most far-right elements of our state.”

Paxton’s legacy can’t be so easily undone because it was never really his legacy to begin with. It took a village to create someone like this, and he is molded in the image of his creators. Most of the people and organizations that seeded Paxton’s rise—the forces that created not just one Ken Paxton, but many—have continued on the trajectory that brought a mob to the Capitol. Only the fringiest of lawyers have faced sanction. Only a handful of dissenters have broken ranks. The Federalist Society has taken no public steps to reckon with how close its members brought the country to a coup. The Republican Attorneys General Association, whose political arm ran robocalls advertising the “Stop the Steal” rally, promoted the man who signed off on them. And the Republican attorneys general themselves simply got back to work. Someone, after all, still has to go into the office, sue Joe Biden, and go home.