Olha Martynyuk had purchased a plane ticket to Switzerland for Wednesday, February 23. The 36-year-old professor of the history of science and technology at the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute had long planned the three-week working vacation in Basel that she was going to combine with visiting her boyfriend. She had packed a small backpack with a pingpong paddle (“for fun”), hiking clothes, a swimming suit, and one extra pair of jeans. She was familiar with Kyiv’s nearby airport and didn’t think she would have to get there too many hours in advance. “I thought there was no chance I’d get stuck in traffic if I’m moving in the opposite direction from the city center,” she told me over the phone. “But it was wishful thinking.” The highways were so jammed with traffic that the trip that ordinarily was only 30 minutes took an hours. She arrived at the airport 10 minutes after the gate closed.

Martynyuk, who was born in Lviv, a Western Ukrainian city about 300 miles from Kyiv and close to the Polish border, returned to her apartment and booked another flight for that Friday. But the following morning, as she was sleeping, Russia had made good on weeks of threats and invaded Ukraine. Everything had changed, and Martynyuk became one of the estimated 600,000-plus Ukrainian refugees who have fled by car, bus, and foot to Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, Moldova, and other countries. I spoke with Martynyuk from Switzerland about her decision to flee her country and all that she has left behind. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

On preparing to go: I came back home on that day, and I took some stuff out of my backpack, but it was kind of ready. I understood that there may be some trouble in Ukraine so I basically took all the cash I had at home with me and sent a box of things to my mother in Lviv: certificates, diplomas, medical cards, love letters. At five in the morning on February 24, the day after I had missed a flight and the day before I was supposed to leave with a new ticket, I woke up just before 6 a.m. from explosions. I could feel the building, a nine-story concrete old Soviet bloc building, shake and I could hear the explosions. I didn’t understand what was happening. I couldn’t see anything out the window. I wanted someone to explain to me what to do. It looked like maybe a gas explosion in the building. I got dressed, went to the kitchen, put my laptop, iPhone, and chargers in my backpack. I hastily took my backpacks and I left the building. I did not use the elevator.

It was all quiet. I was the only one to leave the building, and for a while I thought maybe I’m doing something unnecessary. And at that moment, I heard more explosions and I could see an orange glow behind the building. I understood this was serious. I decided to go to the shelter even before the alarms started. I had a shelter in mind. There’s a new swimming pool and a university nearby and I noticed they had four shelters. I decided to check the news and I read quickly two headlines: one that we had been invaded and the other that there were explosions in Kyiv, Odesa, and other big cities. So I thought I’d make another short run to the metro station and try to go to one of the suburbs where my relatives live and where my father is. I could see some people packing their stuff into their cars. There was panic.

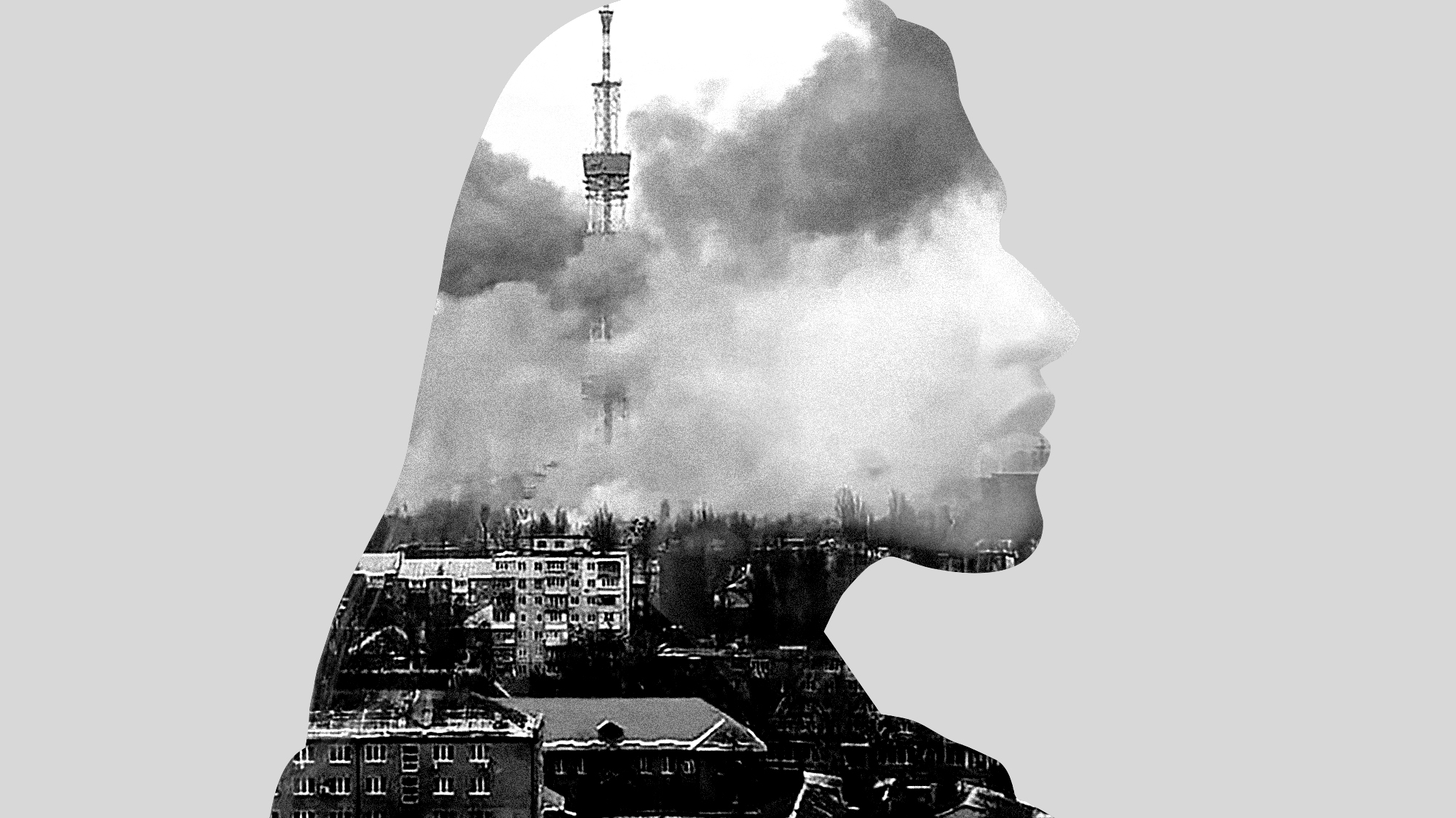

Olha Martynyuk woke up to explosions on February 24.

Olha Martynyuk

My relatives called me and told me the war had started. I told them I knew everything. I rushed to the suburban railway station but on the way, I got a better idea. I thought maybe I could simply take a train to Lviv, which is considered to be safer. It was 6:40 a.m. All the tickets were sold out. I was checking every 15 seconds and then all of a sudden, I found a ticket. But the train would have departed in 10 minutes; I was not sure if I could make it. I was running up the escalator with my two backpacks. I was severely thirsty. I hopped on the train at the very last moment. I had a strong impression that I was fleeing before the huge wave of refugees started. I bought the last train ticket. But I had no doubt that very soon even this would have been impossible. I guess I was lucky to have my backpacks ready.

On the journey: I thought, well, this same train is going to Poland, maybe it’s wiser to cross the border. I was still hesitant if I should leave with my parents and friends still there. Leaving means you would not fight in Ukraine, and I feel a little treasonous for that. Both of my parents really insisted that I go to Poland. But I could see that every minute there are fewer and fewer tickets. So I bought the ticket for the same train from Lviv to Przemysl, which is on the Polish side, and decided to think more about it. The train was moving very slow for safety measures, not more than 40 miles per hour. Instead of a seven-hour train ride, I spent 14 hours on the train with no food. This train was full. Everyone was staring at their phones. If you didn’t know the language and didn’t understand that these people are watching TV news about the invasion, maybe you would have noticed nothing. Looking out the window from the train I was thinking how absolutely beautiful the region was—50 shades of green and gray.

The Polish border control was a lot more friendly than it normally is. I was really happy that Poland explicitly chose to be friendly to Ukrainian refugees. But that was just the very beginning. There were additional seats on the train station, some folding beds, and warm soup, tea, and coffee. At that point, it was a very warm atmosphere. It’s so much different there now. This was such a difficult journey and I can hardly imagine how the people feel after standing on the border in line for 24 or 72 hours. I was lucky because I have a friend in Krakow and she bought a train ticket for me to go there. But most of the people who arrived with me had to sleep on the train station.

Martynyuk’s boyfriend then booked her on a flight to Basel with a layover in Frankfurt.

On looking back: I still don’t know if this was the right decision. If I were in Lviv, I could maybe run to the supermarket to fetch some food, check the news, and let my mother sleep. We could sleep in shifts. I don’t think I would be a good fighter. Had I known what was happening, I would have taken some training, but I’ve never held weapons in my hands. I never shot. But I guess I would be able to do that in principle. I was unprepared. I didn’t think these bad things would take place. These benign explosions were already so scary. I’m still afraid to go to sleep because I can remember waking up from the explosions.

On the one hand, I’m sorry I cannot help out my mother or someone else. I’m sorry that I’m not fighting for my home. I thought that if I go abroad, I can mobilize my international friends and collect donations. I hope that I’m doing something useful. But overall, I’m feeling guilty and not feeling so good about it. It’s nice to be in a safe place but I’m having an awful feeling of guilt. I’m feeling guilty because my friends are there and my parents are there.

Olha Martynyuk woke up to explosions on February 24.

Courtesy of Olha Martynyuk

I call my mom and my dad every day, morning, and evening. My mother lives between two military facilities and those are like number-one targets. I hoped that she would go to her friend’s place, but my mother never left her building. She stays in her apartment with her cat. She moved her orchid away from the window so that if there’s anything bad happening the orchid does not suffer and her cat is hiding and keeping silent. Many people are simply unable to leave their pets, especially for Ukrainians who don’t own a car.

There have been seven air raid alarms, and my mother goes down to the shelter each time. We are a little lucky because the shelter is in the building, a big five-story building on a slope, and the basement goes kind of deep. Today she went to the market to buy some food and she said the supermarkets were empty as in the late Soviet Union. But she could buy fresh produce that’s perishable. Whenever there’s like a small threat to my mother’s safety, I go crazy. I just start crying. I can hardly cope with it. It’s also a little selfish. There are so many bad things going on in Ukraine, and there are so many awful places to be, but I’m worried about my mom.

My father is in the suburb of Kyiv in a very dangerous situation. It’s basically a frontline there. My father’s always been sort of a little paranoid. He has always seen Russian spies or former KGB people all around. But nowadays his paranoid thinking is absolutely relevant. Both of my parents have always been optimistic. I think always being optimistic means sometimes not really feeling the problems. But I feel like there’s a connection between their very optimistic attitude to life and being actually functional in this situation. I met some people who just don’t know what to do. They don’t eat. They smoke a lot. This is maybe more of an adequate reaction. But somehow people who are optimistic seem like they can take care of themselves and deal with what’s happening.

It’s so crystal clear that very few people in Kyiv would like to live under Putin. This was absolute nonsense. Why would you want to send all these young, poorly trained people and armored vehicles into a city where no one is waiting for you? Where you have no chances of winning the hearts of the population? Even if there were some Putin supporters in Ukraine, they can see what a catastrophic war this is. This is crazy. This is awful. Right now we are struggling. There’s a lot of damage being done to all of us. It’s a trauma that will stay with us for a long time. Maybe that’s his plan, but his own society will also get traumatized. I’m very happy to see Russians protesting, risking their wellbeing and health. We all risked something and freedom comes at a cost. I think it’s our mutual responsibility. Putin attacked not only Ukraine but humanity.