Mother Jones illulstration; Alexey Nikolsky/AFP/Getty; Ukrainian Presidential Press Office/AP; Getty

Many people in the global north—at least many voices in the media—are rather optimistic about Ukraine’s ability to dominate the “information war” unleashed by Russia’s invasion. Writers in the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Politico, and the Financial Times, and at as many as a dozen other publications have written stories eagerly declaring Ukraine the winner. Indeed, popular opinion in the US seems largely united, and, from a certain vantage point, in broad alignment with a global condemnation. Against that backdrop, Ukraine’s information dominance is an enticing narrative—the clear aggressor in all of its military might is getting its ass kicked online by a savvier, scrappier underdog. Russia’s military is many times larger and more resourced than Ukraine’s. But even in a war of asymmetric powers, there are possible avenues to victory.

In the corners of Twitter where I hang out, filled mostly with Americans and people in countries who have benefited from the consequences of American foreign policy, these declarations seem mostly accurate. A Russian claim about photos of a hospital bombing in Mariupol, Ukraine, being faked was solidly ratioed by doubters before being taken down from Twitter. Russian state media has been excised from major platforms. But across the wider internet, declarations of a Ukrainian information victory might be a little premature and incomplete.

“A lot of the people who are saying ‘game over’ are looking just in their own circles,” Elise Thomas, an Australia-based disinformation researcher and open-source intelligence analyst for the Institute of Strategic Dialogue, a London think tank, told me. In her research, she’s noticed that positions on Ukraine and Russia are contested globally in ways that they currently aren’t in the US.

Journalists and writers in South Africa, Brazil, Venezuela, and elsewhere have adopted stances that are more critical of Ukraine and the US than they are of Putin. In the world’s two most populated countries, China and India, Ukraine is not at all winning any information war. Chinese social media users have cheered on the invasion with hashtags on Weibo. Like Russian media, Chinese media has characterized the invasion as an anti-fascist effort against an autocratic Ukrainian government, which it has accused of using human shields, according to the New York Times. Earlier this month, the #IStandWithPutin hashtag trended worldwide, particularly heavily in India as the country, which has generally aligned itself with Russia, abstained from signing on to a United Nations resolution condemning the invasion.

Even if you think this doesn’t matter that much in a geopolitical order still dominated by the US, the strong, near universal domestic support for Ukraine that has so far defined our domestic scene isn’t a given. To date, the American right has not firmly settled on a unified position on the invasion. Speaking out against Ukraine seems unthinkable in the current moment, but large swaths of the contemporary right do not care about boundaries of acceptability established by the center-left and even conservative moderates.

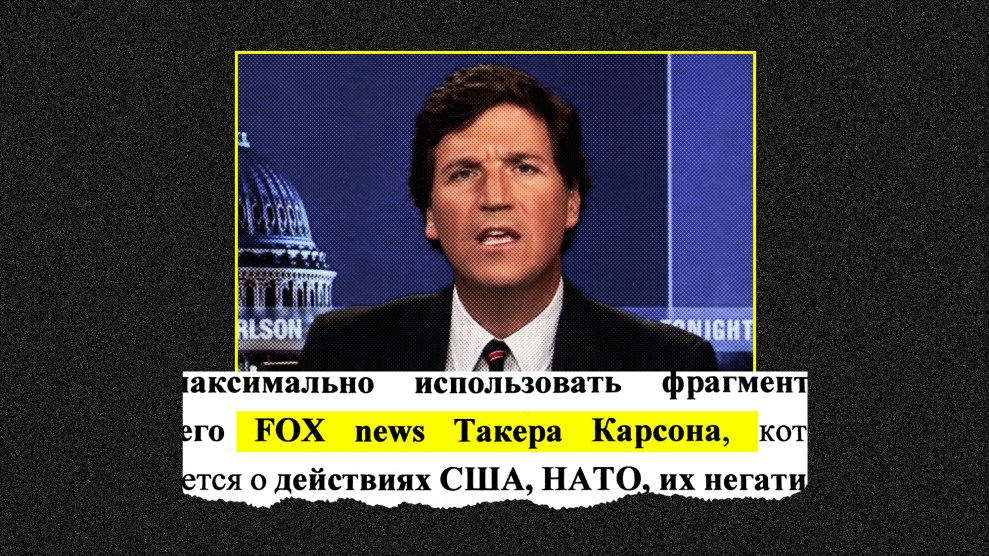

Though the American right still hasn’t fully coalesced on a clear position, internet researchers like Sara Aniano have documented how they are trending toward a Ukraine-skeptical one. Fringe influencers and communities that nonetheless maintain influence in right-wing spaces—like the white nationalist internet personality Nick Fuentes, and QAnon and adjacent conspiratorial groups—have already sided with Russia. The latter have come to embrace the debunked conspiracy that the US is funding bioweapons laboratories in Ukraine. Thomas, who monitors what she describes as the international “QAnon-inflected” conspiratorial community, has observed their positions moving “almost one to one with Russian propaganda.” Higher-profile and very influential figures like Tucker Carlson have adopted pro-Russian positions, to the delight of Russian state media—as documented by my colleague David Corn.

Jared Holt, a research fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab who studies the far right, has been thinking about how the national narrative about January 6 changed over time, and what that process could portend for the narrative over Ukraine.

“Immediately after the attack, there was widespread condemnation. There were calls for people to be tried to the fullest extent of the law and others were siding with law enforcement agencies,” Holt recalled. “But then this harder right-wing conspiratorial faction of the GOP started leveraging that conspiratorial torque that exists. Very gradually and then all at once, the script flipped to where now the Republican National Committee is calling January 6 a legitimate form of protest.”

With the same wings of the conspiratorial right pushing anti-Ukraine positions, Holt says it’s possible, though not certain, that they could in time remake the broader movement’s position on Ukraine. But he warns that “to dismiss how effective these fringes can be at shaping narratives I think would be a mistake.”

Even without consolidating conservative opinion on the right, pro-Putin, right-wing voices could be effective in reshaping the American information environment. Since the invasion, tech platforms have aggressively blocked and limited the reach of Russian propaganda and state media. But Silicon Valley companies are notoriously afraid of being accused of having bias against conservatives to the point where they’ve hesitated to crack down on white power accounts, out of concern for potential collateral damage to conservative accounts moving in similar online networks. If the right becomes more vocally pro-Russia, would the platforms continue to be as emboldened in fighting Russian propaganda?

In 2016, Russian troll farms tried to draw on actual endemic racism in the US and the tensions around it. Thomas told me that she’s seeing a potential version of this play out today. She’s seen accounts that she knows push Russian propaganda lean in to reports of African and Asian students being discriminated against in their attempts to flee Ukraine. “It’s would be a classic example of something that is a serious, real issue that Russia is trying to drive a wedge even further into,” Thomas said.

Time also benefits Russia in the sense it doesn’t need to win sentiment so much as it does to create a system that questions pro-Ukrainian sentiment. In one of the few pieces to look into Ukraine’s position in the information war and not declare it the clear winner, the Atlantic’s Charlie Warzel noted that “Universally accepted narratives can be fleeting, though, especially when media scrutiny fades.” As time goes on and the internet is flooded with more and more information that isn’t always reliable, people have more iterations of reality to pick from.

Warzel also addressed the difficult fact that Ukraine “has its own propaganda aims.” Even if that’s a justified, rational tactic by any country under invasion, it could eventually turn people off. “There’s been a dancing around of this fact, because Ukraine is obviously the victim,” Thomas said. “But they do have their information tactics. It’s an interesting ethical question for the field. What do we do when an actor we like is using these tactics?”

Russia, as a part of its own propaganda operation, has gotten attention for accusing Ukraine of spreading false information. But Thomas posits that Russian information warriors, having expected no conflict or a more limited one, may not yet have had time to craft a full-fledged information battle plan. While Russia’s disinformation attack on the 2016 election was real, its actual effectiveness has always been hard to measure. While Russia has long disseminated information regarding Ukraine in the service of its own interests, Thomas believes wartime information campaigns take a bit of time to pull off. Information must be seeded, specific targets must be identified, and narratives need repetition and time to build.

Mike Pepi, a writer and tech critic, addressed the issue of broad information overload during a June episode of the podcast of internet researcher and artist Josh Citarella. “Information is the enemy of narrative. The more information, the more doubtful the narrative becomes,” Pepi said, citing his manifesto-like Elements of Technology Criticism. “When you introduce too much information into a system or discourse, you’re constantly able to poke holes in any narrative,” Pepi continued.

Of course, the invasion hadn’t happened. But over the last two weeks, a nearly endless stream of reports, videos, and footage have emerged from Ukraine. That much content provides all the data points needed to construct endless stories comporting with your beliefs and the corresponding beliefs of the people you trust. Because of the vast quantities of information now available to everyone, no one is limited to a specific narrative. None of them have to be accurate, they just have to look like they are to enough people.