One hundred and seventeen miles Northwest of Savannah, nestled between fields of cotton and grazing livestock, sits the majority-Black town of Wrightsville, Georgia (population: 3,638).

The sleepy southern hamlet is where Curtis Dixon, now 67, taught GOP Senate nominee Herschel Walker social studies, coached him in football, and drove him to and from practice at Johnson County High School.

But from the front porch of his craftsman ranch home in Wrightsville, Dixon told me he is not supporting the candidacy of the onetime star athlete who helped the Johnson County High School Trojans bring home the state championship football title in 1979, won the 1982 Heisman trophy as a standout running back at the University of Georgia (UGA), and played 12 seasons in the NFL.

“Herschel is a celebrity,” Dixon said. “We don’t need a celebrity, because we’re at the point where we’re about to lose our democracy.”

Walker’s performance during his October 14 debate against incumbent Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock merely confirmed Dixon’s misgivings. In response to a comment Warnock made about a measure in the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) that lowers insulin prices, Walker, who opposed that bill, erroneously claimed that “unless you are eating right,” insulin “does no good.”

Football coaches Gary Phillips, Curtis Dixon (far left), Tommy Jordan, James Usher, and Jimmy Moore from the 1980 Johnson County High School Yearbook.

Abby Vesoulis/Harlie Fulford Memorial Library

Diabetes, which affects 37 million Americans (and, disproportionately, Black Americans), can have little to do with eating habits. Certain types can be solely based on genetic factors or random bad luck, and lots of diabetics depend on insulin to survive—even if they eat incredibly healthy.

“I do 10,000 steps a day,” said Dixon, who is diabetic. “I monitor what I eat. I’m on medicine, but my medicine won’t allow me to lose weight. I’m offended for him to come tell me to eat better.”

If the moment highlighted that Walker does not understand a common health ailment, one that is especially ubiquitous in the South, it also represented a central critique of Walker’s candidacy in general: that he does not care to understand many of the topics—health care, housing, food security, the economy—on which he’d be responsible for legislating as a US Senator.

Walker’s comments about everything from diabetes to air quality have raised eyebrows, and he has generated headlines for assorted scandals, including past violent episodes and recent allegations that the anti-abortion candidate paid for at least one woman’s abortion. (A second woman came forward anonymously this week to claim that Walker had paid for her abortion, too.) And in his hometown, Walker is a controversial subject; many residents did not want to talk about him.

“I don’t know a Herschel Walker,” one middle-aged Black man retorted sarcastically when I approached him as he worked on an old car at the end of a driveway.

Walker’s name is pretty hard to miss in Wrightsville. Less than a mile away was Herschel Walker Drive, which led to Johnson County High School’s Herschel Walker Football Field. A couple blocks away from there sat Herschel Walker’s campaign bus, replete with a giant picture of Walker’s face. The vehicle was parked in front of a florist shop adorned with a giant banner reading, “RUN HERSCHEL RUN.”

One disabled woman in Wrightsville, also Black, shared that she felt Walker had forgotten about the plights of Wrightsville citizens while he’s been off campaigning for Senate in other corners of the state. She was frustrated that a PAC supporting Walker gave $25 gas vouchers to people in Atlanta. “Why didn’t he do that in his own town?” said the woman, who asked for anonymity because it’s a tight-knit community and Walker’s mother still lives nearby. She complained that her disability payments and food stamps, types of government benefits that Walker does not support raising, are far too low to live off of, especially as inflation remains near a 40-year-high and that just one full-service grocery store remains open in the small rural area.

“If I do vote, it won’t be for him,” said another Black woman, who also asked to remain anonymous.

Of all the residents willing to talk to me, half told me they felt Walker had turned their back on them and their needs in Wrightsville, where the median annual income is $26,250, and the main attractions are a Confederate soldier memorial and a diner called Cornbread Cafe. The other half —those who supported Walker—were all white.

“Black people aren’t for Herschel, that’s what I hear,” said Gerald Perdue, a white man who was spitting tobacco while we chatted. “I’ve never voted for a Black, but I’m going to vote for him.”

The racial animosity runs deep in Wrightsville.

Less than 15 years before Walker was born, at least 300 members of the Ku Klux Klan held a parade and burned crosses in Wrightsville in an effort to intimidate Black residents out of voting. It worked. Not a single Black citizen of the town cast a ballot in the 1948 primary election.

During Walker’s late teenage years, white segregationists routinely clashed with Black Wrightsville residents who were protesting over the absence of Black people in city and county-level positions and the presence of poor infrastructure in predominantly-Black corners of the town. At least once, these white segregationists used clubs to attack Black demonstrators, who later filed a complaint that the white sheriff, Roland Attaway, joined in on the violence. On a different occasion, the same white sheriff and other law enforcement conducted warrantless raids on Black individuals in their homes and churches.

“Sheriff Attaway and members of the police agencies invaded the Needler A.M.E. Church of Wrightsville, arrested individuals who were there, without search or arrest warrants, and Sheriff Attaway demanded that the Black citizens ‘Get their God damn Black asses out’ of the church,’” according to lawsuits cited in a 1980 US House Judiciary Committee hearing examining an increasing rate of violence against communities of color. (The largest lawsuit, filed by 48 of the Black protesters, was dismissed by an all-white jury in 1983.)

At least three people were injured by gunfire amid the period of heightened conflict, including 9-year-old Constance Folsom, who was shot in the head and neck when likely Klansmen fired into her Black family’s mobile home in April 1980. At the time, Walker was a senior at Johnson County High School.

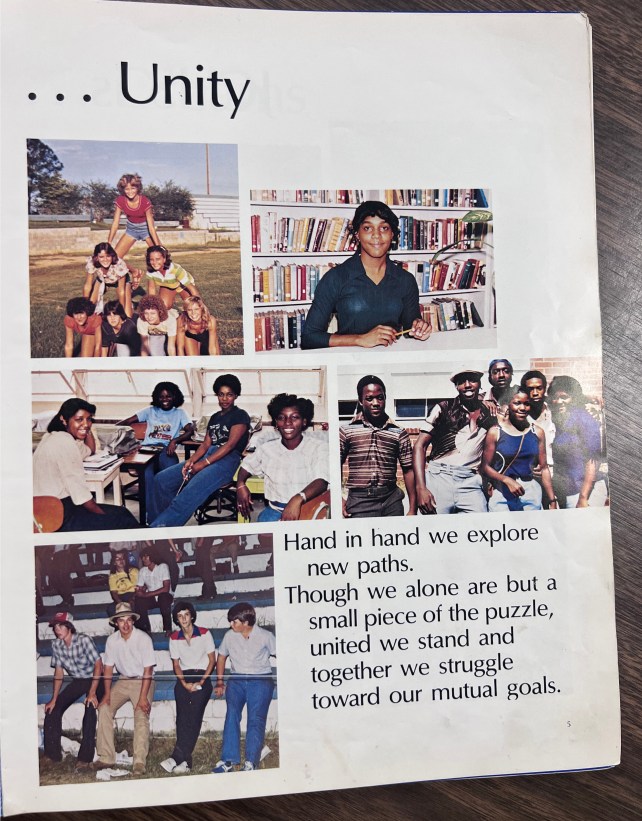

“JCHS is… Unity” this spread from the 1980 yearbook said.

Abby Vesoulis/Harlie Fulford Memorial Library

The divisions extended to the high school itself. High school yearbook photos from Walker’s senior year reviewed by Mother Jones show very little fraternization among white and Black students outside of school-sponsored clubs. Under one yearbook page header that reads “Unity,” four large group photos appear: two depict all white students and two depict all Black ones.

Walker got flak from fellow Black classmates for breaking this mold. “Kids were calling him honky-lover, saying he hung around with more white people than Black,” Milt Moorman, a Black high school football teammate, told famed sports reporter Gary Smith in the 1980s.

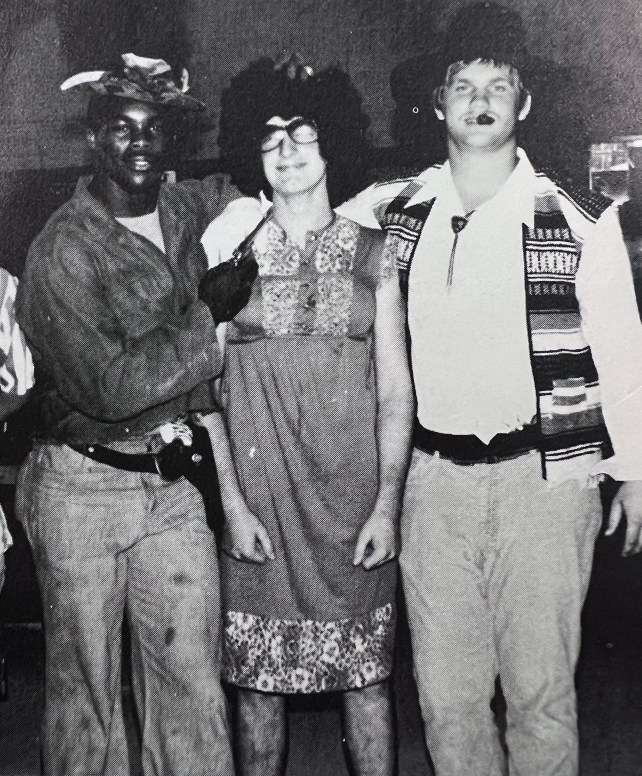

In one of the rare non-club photos showing white and Black students together, Walker appears as the sole Black student among several white classmates, casually holding a toy gun to one of their necks while wearing a costume during a week of homecoming festivities.

Herschel Walker (left) appears with a toy gun and gun holster during Homecoming spirit week in the 1980 yearbook.

Abby Vesoulis/Harlie Fulford Memorial Library

Walker faced similar critiques for his relationships with white people in college. “There has been a lot of discussion by Black women that Herschel is white-oriented,” said Mel Lattany, one of Walker’s Black UGA track teammates, according to the 2006 book Echoes of Georgia Football.

The same book explains Walker’s reasoning for not getting taking part in the early 1980s protests back home. “I didn’t want to get involved in something I didn’t know much about,” he told a reporter while at UGA.

In his own 2008 memoir about having Dissociative Identity Disorder, Walker discussed that decision in more depth. “I never really liked the idea that I was supposed to represent my people,” he said, adding, “I could never really be fully accepted by the white students, and the African American students either resented me or distrusted me for what they perceived as my failure to stand with them.”

Recent literature from Walker’s campaign indicate his complex feelings about being representative of his race are ongoing. “As I run for Senate, I ask people to vote for me if they think I’m the best candidate for the job—not because of my skin color. I’m tired of some people dividing Americans based on race,” he said in four recent campaign fundraising emails.

But the long-running racism in his town was difficult to overlook. Up until at least 2003, the county’s proms were still segregated by race, and until at least 2007, the school district was still under court supervision for its desegregation efforts, according to a report from the Georgia Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights.

Racial divisions are nearly as palpable today—and so are the divisions among white and Black residents of Wrightsville when it comes to Walker and his Senate bid.

Livia Claxton, a white woman whose front yard featured a “Women for Herschel” sign, was emphatic about her support for Walker, who graduated from Johnson County High School a few years before she did. Claxton used to drop off footballs for Walker to sign for her clients in the trucking industry. “We would just take them out there and leave them with his mama. When he came home, he’d autograph all of them for us and never charged a dime,” she said.

Everybody who supported Walker mentioned his football prowess. “He would go in the end zone and he would have one guy around each ankle,” she said. “It never slowed him down.”

Gerald Perdue recalled driving 20 miles into town on Friday nights to see Walker play: “I lived in Washington County at that time, but when he was playing ball, a bunch of us would get together and come down here and watch him.”

Others continued to follow his sports career at UGA in Athens. “When he went to Georgia,” Claxton said, “everybody in town got season tickets.”

Nobody who spoke to me discounted that Walker loved to win, and was very good at it. But some felt that alone did not qualify him to win this US Senate seat.

“Herschel had no intention of running for Senate,” Dixon, Walker’s former teacher and coach, said. “Somebody planted that seed, and they kept saying ‘Run Herschel Run.’ He kept hearing this over and over, that ‘You’re gonna win. Everybody knows you. Name recognition.’ There is some truth to some of that. But we need somebody who can represent us.”