Ten years ago, Marilyn Muller began to suspect that her kindergarten daughter, Lauryn, was struggling with reading. Lauryn, a bright child, seemed mystified by the process of sounding out simple words. Still, the teachers at the top-rated Massachusetts public school reassured Muller that nothing was wrong, and Lauryn would pick up the skill—eventually. Surely they knew what they were talking about. Their reading curriculum was well-regarded, and one that encouraged children to use context clues when they couldn’t decode a word. The class was organized into leveled reading groups—bronze, silver, gold, and platinum—with everyone starting out the year in the bronze group. By year’s end, everyone had moved up to a new level—except Lauryn. Muller’s daughter was the only kindergartner stuck in bronze all year.

First grade was no better. The teachers continued to brush off Muller’s concerns—but she couldn’t help but worry for all sorts of reasons, especially because not being able to read was starting to affect her daughter emotionally. Tears started each day, as Lauryn began to refuse to go to school in the mornings. Finally, Muller brought Lauryn in for a private neuropsychological evaluation, and the psychologist who tested her found that her daughter was dyslexic. After a long battle with the school, Muller eventually convinced them to provide appropriate services—something to which all students are entitled by law.

In Lauryn’s case, this meant that her current reading curriculum should have been replaced by a method of known as the structured literacy approach. Instead of guessing and looking for context clues, structured literacy—also known as phonics—teaches students how to map sounds onto letters to decode words. There was only one problem: Muller discovered that the teacher the school assigned to Lauren wasn’t trained in structured literacy. Lauryn continued to struggle.

Muller didn’t know it at the time, but she had stumbled into an educational controversy that in recent months has turned into something of a scandal. A spate of recent reporting—in podcasts, national magazines, and major newspapers—has highlighted new research finding that the balanced literacy approach wasn’t as effective as a phonics-based approach for most students—learning disabled or typical. And the national embrace of balanced literacy was particularly bad for low-income students of color. Today, a staggering third of all children—and half of all Black children—read below grade level. In May, leaders in the country’s largest school system of New York City officially announced plans to transition away from a balanced literacy curriculum and apologized for the harm they had caused. Addressing students and parents in a recent New York Times interview, Chancellor David C. Banks said, “It’s not your fault. It’s not your child’s fault. It was our fault. This is the beginning of a massive turnaround.” Understandably, parents are outraged.

There are perhaps no groups more poised to capitalize on parental outrage than those that are part of the ascendant parents’ rights movement. These politically conservative groups, which include Moms for Liberty (55,000 members), No Left Turn in Education (49,000 Facebook followers), and Parents Defending Education (26,000 Twitter followers), charge that schools have overstepped their bounds by teaching students progressive values—acceptance of all sexual and gender identities, for instance, or how to fight against racism—instead of focusing solely on academics. Now, these groups have taken up the failure of balanced-literacy instruction as further evidence of the utter failure of progressive education in perhaps the most important skill a child learns in school. In the process, they’ve launched the latest version of an age-old political fight over reading. Basically, the argument from parents’ rights groups can be boiled down to this: Don’t believe us that public schools have sacrificed education at the altar of progressive educational schemes? Just look at how miserably they’ve failed in teaching our kids to read.

By the time Lauryn was in third grade, Muller had had enough. She pulled her daughter out of public school and enrolled her in a special school for students with learning differences, where the teachers adhered strictly to the structured literacy method. The school was astronomically expensive—about $50,000 a year. But to Muller, it was well worth it. Within months, Lauryn was reading—and she was happy. Muller credits the school—and its reading curriculum—with saving her daughter’s life. When Muller talks, you can hear the emotion in her voice, the quiet rage about how a school she trusted did so much damage to her daughter. She characterized Lauryn’s experiences in a recent tweet as, “the school-based traumas that she endured at the hands of nefarious educators in broken and chronically noncompliant state-run and locally-controlled public schools.” Balanced literacy lessons, she told me, are “harmful to most kids, but they can be a death sentence for a child like mine.”

Controversies around reading instruction are nothing new—the wars over the relative merits of various approaches seem to come to a head every few years. This most recent battle is the result of several recent widely read pieces in the New York Times, as well as the 2022 podcast series Sold a Story, all of which highlighted the work of an influential education professor at Columbia University’s Teachers College named Lucy Calkins. Beginning in the 1990s, Calkins developed an approach to reading instruction that emphasized reading aloud to children and igniting their excitement about books. “There is simply nothing that makes teaching reading easier, that gets kids reading with greater volume, or that lifts reading skills higher than a collection of truly fabulous books,” Calkins wrote in a recent article on her website about the importance of classroom libraries. Calkins’ work caught on, and it’s not hard to see why: A classroom where children fall in love with books sounds objectively better than one that imposes dreary drills about “I” before “E.” Since 2014, Calkins has sold an early readers edition of her curriculum, called Units of Study, to school districts. Today, according to the New York Times, a quarter of the schools in the United States use it, and some have paid thousands of dollars for a consultation with a member of Calkins’ team.

But as literacy researchers began to dig into the outcomes of students who went through curricula inspired by Calkins, they found an unsettling trend: For many kids, it simply didn’t work. In a 2020 report, a team of reading researchers at the educational consulting group Student Achievement Partners (SAP) concluded that Calkins’ approach was only effective for students who had already received outside reading instruction. “Children who arrive at school already reading or primed to read, researchers agreed, may integrate seamlessly into the routines of the [Calkins] model and maintain a successful reading trajectory,” the authors wrote. “However, children who need additional practice opportunities in a specific area of reading or language development likely would not.” The most notable failure of the Calkins curriculum, the report said, was that it didn’t include nearly enough explicit instruction in phonics, which researchers have long known is critical for building the foundation for reading.

The findings about balanced literacy curricula—both that of Calkins’ and a similar one called Fountas & Pinnell—are beginning to make waves. In the last few years, 31 states have made laws that require schools to employ structured literacy techniques. After increasing pressure, last year, Calkins herself revised her curriculum to include more emphasis on phonics, though she stopped short of recanting her earlier ideas about how children learn to read.

The backlash against Calkins and her methods has been harsh. “She’s essentially asking teachers to throw kids into the deep end of the pool, tell them they’re ‘swimmers,’ and let them sink,” wrote education journalist Natalie Wexler in a 2021 article for Forbes. A parody Twitter account called Lucy Falsekins has thousands of followers. (A recent tweet: “Please, we need a ceasefire on this endless reading war. Can’t we all just agree to do what’s worst for kids? Is that asking too much?”) Kareem Weaver, an activist who leads the NAACP’s push for evidence-based reading instruction, told the New York Times last year, “The kids can’t read—nobody wants to just say that.”

According to Calkins, the recent reporting missed important nuance. In an emailed response to questions from Mother Jones, Calkins emphasized that she has long advocated for the inclusion of phonics in the reading curriculum. “I have always recognized that children need both decoding and comprehension,” she wrote, though she worries that the recent controversy will “push us to a place where comprehension is ignored and phonics overemphasized.” She added that she believes that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to teaching reading. Instead, she favors “a workshop approach to teaching that allows teachers the latitude to make the instructional decisions they need and to vary their instruction based on children’s needs.”

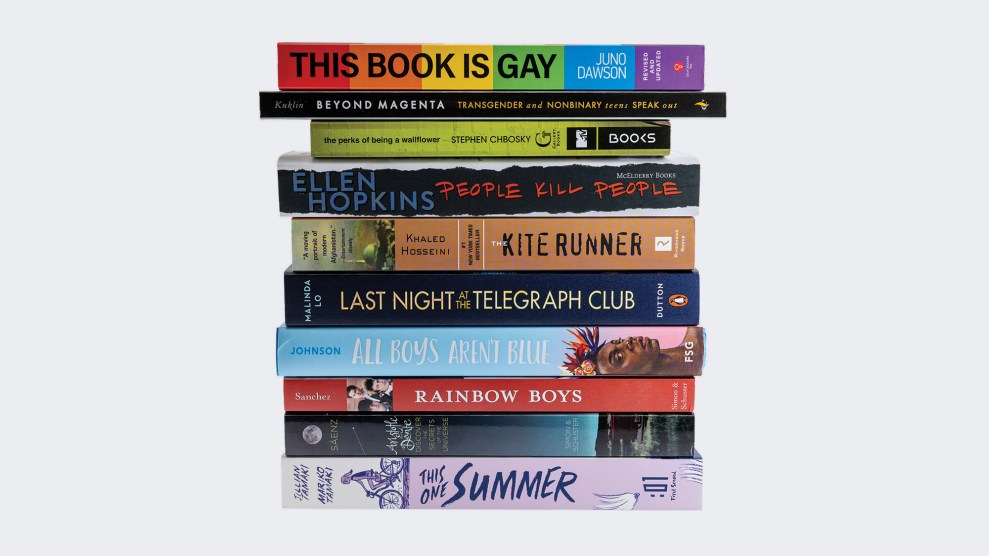

Even as the conflict about balanced literacy was playing out in school districts, the burgeoning parents’ rights movement—which began with conservatives’ outrage over school closures and mask mandates during the pandemic and became a politically powerful juggernaut by decrying “woke” curriculum—had hit a kind of a roadblock. For the last two years, a loose coalition of groups led by Moms for Liberty had set their sights on taking over school boards and ridding schools of books that they considered pornographic. These titles varied by district, but they often included books about queer identity and racism. Some were just about difficult topics: a graphic novel version of The Diary of Anne Frank, for example, or a picture book about segregation by Ruby Bridges.

As it turned out, banning books did not have the popular appeal of stopping mask mandates or taking over school boards. A Publishers Weekly poll last year found that 75 percent of respondents said “preventing book banning” was important to them when voting. The book banners began to backpedal. “No one is looking to ban books,” the Moms for Liberty assured its followers on Twitter in April.

So, parents’ rights groups needed a new crusade—and they found it in parents’ anger about Lucy Calkins’ methods for reading instruction. This spring, Moms for Liberty has begun to use failure in literacy teaching as a kind of foil for its criticisms of curriculum content. “There is a lot of time being spent on ‘social-emotional learning’ and not so much time being spent on effective reading instruction in the classroom,” the Moms for Liberty account tweeted on May 21. “Why is literacy not being prioritized like sexual education is currently? Why does a 5yo need to learn about gender identity?” On June 1, Moms for Liberty founder Tiffany Justice tweeted, “It’s pride month and I can’t help thinking that Americans want to be able to be proud of the education our children are receiving in our public schools. We can’t right now.” Other conservative influencers have picked up literacy as a culture-war talking point, as well.

“I’m a dad who wants schools to teach kids how to read—not how to be gender fluid,” complained the writer of an op-ed published on the Fox News website last April.

The anti-woke education advocacy group No Left Turn in Education, which was founded in 2020 to oppose anti-racist curriculum in the wake of the protests that erupted after the murder of George Floyd, makes similar complaints in its social media posts. For example, last year, the group declared on its Facebook page, “The fact that our K-12 schools seem more interested in the sexual orientation, preferences, and development of our children than they are in their literacy and math proficiency should alarm every parent.” The post received 2,000 likes. James Lindsay, a conservative commentator who spoke about the secret Marxist agenda of public schools at last year’s Moms for Liberty conference, speculated on Twitter that the problem was not Lucy Calkins but a Brazilian philosopher and education scholar named Paolo Freire who may have influenced American schools to ditch phonics for political reasons. Freire “reframed literacy education away from phonics and into a frame of ‘generative words,’” Lindsay tweeted to his 400,000 followers. Rather than teaching ‘nonsensical syllables,’ literacy would involve learning words that raise consciousness, like ‘struggle,’ and literacy was redefined to mean political literacy.”

As serious as the debate about teaching reading has become, I suspected that these ideas—the teaching of LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum is replacing literacy instruction, and that the rejection of phonics was a Marxist plot—were, to put it mildly, a stretch. So, I called up Robert Pondiscio, a senior fellow at the conservative think tank the American Enterprise Institute specializing in K-12 education. Pondiscio, who has written extensively about the failures of the balanced-literacy approach and used to teach in a public school in New York City’s South Bronx neighborhood, agreed that these criticisms of literacy instruction were over the top. As Pondiscio put it in his recent review of James’ Lindsay’s new book that accuses American public schools of a Marxist agenda, “Raising the aimless drift of public education and decades of poor performance to the level of a Q-Anon conspiracy undermines the seriousness of the critique.” But the idea that a signature progressive education movement was a complete disaster? That’s undeniably true. “That method,” Pondiscio said, “just spectacularly failed low-income students of color.”

Today, Lauryn Muller is an honors student entering the tenth grade. Last year, her family moved to Florida so that she could attend a renowned private high school. She will be in classes with typical learners, but if she struggles, the school offers support for children with language-based learning disabilities. Her mother, meanwhile, has become an advocate for structured literacy, telling her story to anyone who will listen.

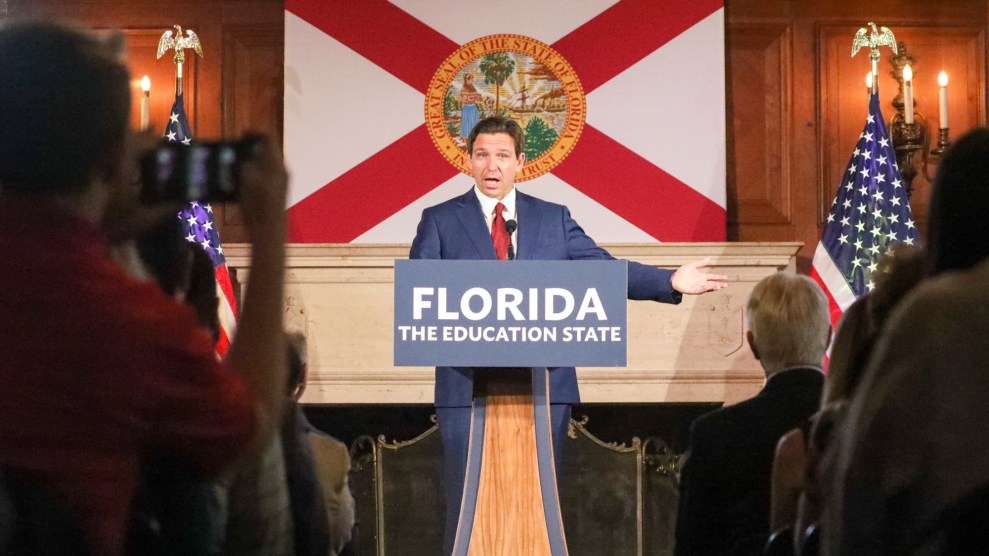

Muller found a large audience at an April conference in Sarasota, Florida, hosted by the Leadership Institute, a conservative group that trains young Republicans, particularly those who want to run for office. The topic of this conference, called the Learn Right Summit, was education. According to the promotional email from Leadership Institute’s vice president of school board leadership programs (and Moms for Liberty co-founder) Bridget Ziegler, the goal was to “help more parents fight this radical indoctrination, reclaim their school board, and protect their children.” In addition to Muller, the lineup of speakers included the newly installed interim president of the New College of Florida—the public liberal arts college that Florida governor and presidential hopeful Ron DeSantis vowed to make over to his own right-wing specifications—as well as James Lindsay, the rejecting-phonics-is-Marxist guy. So popular was Muller’s session at the conference that the Leadership Institute invited her to reprise it in a webinar a few weeks later. An email invite to the event promised that attendees would learn about “Reading: the real crisis in education.”

Muller emphasized that she wasn’t paid for either event. Indeed, she told me that she considered herself fiscally conservative and “socially moderate-slash-liberal” and had no illusions about the Leadership Institute’s arch-conservative activism. But she said she agreed to appear at the conference simply because she wants to spread the word about reading instruction. “I will agree to anyone asking me to speak about literacy,” she told me. “I don’t care if you’re left, right, center because really, it should not be a political issue.”

She did, however, note that there could be an indirect connection between gender identity and reading instruction. Struggling academically can cause students emotional anguish, which she suggested can include gender dysphoria, since “most of the children who have chosen that direction have language-based learning disabilities, like dyslexia.” She added, “My belief is that they were denied the appropriate education.” After this article was published, Muller requested that I add additional context around her comments. She said, “I believe that there is a direct link between the evidence of free appropriate public education noncompliance by public schools and the data showing disproportionate gender dysphoria among children with autism spectrum disorder.” (To be clear, research suggests that transgender people do indeed have higher rates of learning disabilities and autism than their cis-gender counterparts, but there is no evidence that inappropriate education causes gender dysphoria.)

Neither Muller nor anyone else I talked to for this story endorsed the polarization of reading instruction. But we live in an age of political symbols: It only takes a few tweets for seemingly apolitical objects and systems—masks, stores, vaccines,did banks—to fall along party lines. The politicization of reading isn’t new, of course, but in the current climate, it’s becoming a battleground. With the next generation of American citizens caught in the crossfire, the stakes have never been higher.

This article has been updated to include an additional comment that Marilyn Muller made about the connection between education and gender dysphoria.