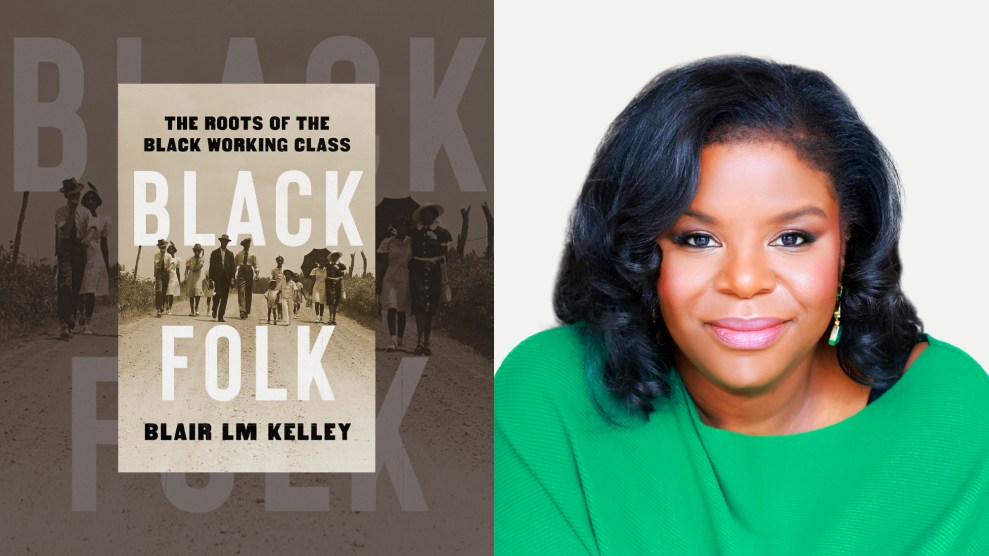

Mother Jones; Katrina Wittkamp

The 2024 presidential election cycle has begun, and the white working class once more has commanded the spotlight. Pollsters obsess over how their economic struggles and resentments influence their political choices. Democrats and Republicans jockey to win their favor, each promising— through different cultural and political appeals—to address their individual and collective needs while igniting a new era of economic prosperity.

But where in this landscape are the direct appeals to the Black working class? This is a group that has experienced political and economic turmoil like few others, while simultaneously expanding the possibilities of the American political system. As Blair Kelley, an acclaimed, award-winning historian of Black history at UNC-Chapel Hill, writes in her new book, Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class, “When Black workers are mentioned, the idea of work is often dropped, instead it becomes a discussion about the poor.” But, in fact, Black workers are the backbone of the labor force. Or as Kelley puts it, “More than 28 percent of 42 million Black people in America today—the majority of the Black working class—are essential workers.”

In Kelley’s hands, modern labor struggles—from UPS workers fighting for a fair contract to Amazon workers demanding better working conditions —become historical epics made possible by the contributions of Black workers centuries ago. We can see the roots of solidarity between poor white workers and rich white capitalists, and how Black workers became a critical force for civil rights. We meet Black laundresses who brought cities to a grinding halt during Reconstruction by organizing powerful unions within a year of leaving slavery.

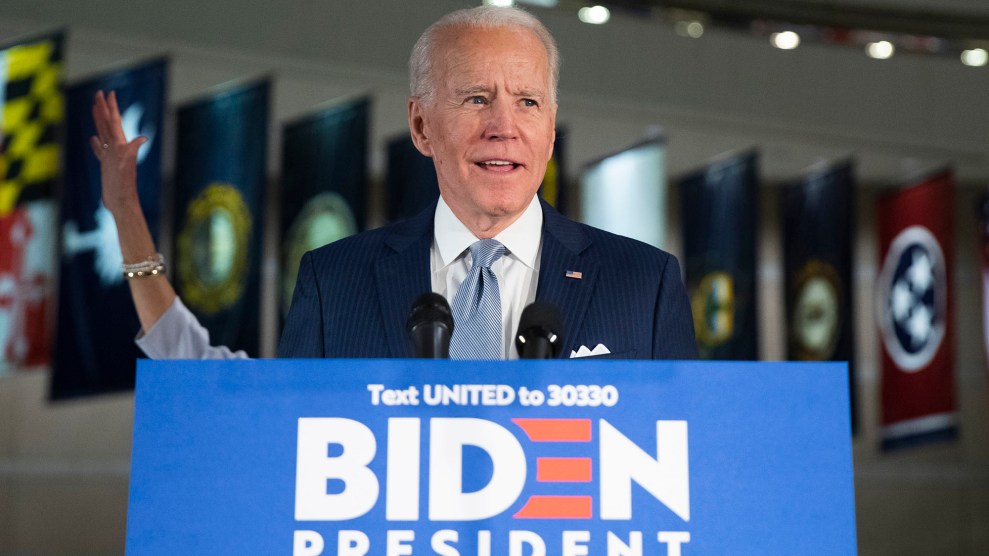

In their struggles and the fabric of their lives, Kelley discovers patterns that help to explain the current political landscape. The trajectory of this history led to the 2020 election when the support of Black working-class voters catapulted candidate Joe Biden to the Democratic nomination and then the presidency. You can see how that electoral bloc made the impossible possible by flipping Georgia despite a global pandemic and widespread voter suppression. As we approach the 2024 presidential race, Black Folk feels especially timely in its compelling argument about the important role Black workers play in shoring up American democracy. I caught up with Blair Kelly over Zoom from her office in Chapel Hill.

There’s been seemingly endless political and media attention on the white working class, but so little focus on the Black working class. Who is the Black working class? What made you decide to write a book about them?

At first, I thought this wasn’t the book for me. I’m not a labor historian or someone who has been studying unions exclusively for a long time. When my editor asked what a book from my perspective as a scholar of Black history would look like, I realized my family was at the heart of how I could approach the question. My family members weren’t necessarily famous labor organizers or people who led wildcat strikes. They worked jobs. They had relationships within the communities that supported them. I wanted to start with them and the humanity behind those who work.

I define the term “Black working class” broadly. It’s probably broader than most scholars might frame it because the book begins with enslavement, and a good Marxist would never start with enslavement. You would begin when people are free. But for me, the roots of Black working people start in our history of being in bondage in this country, our relationships to those institutions, and the ways in which we built community, resistance, and life in spite of enslavement.

You describe Black churches during enslavement as a “launching pad for working-class organization.” Do you see that spirit in modern Black churches today, or has that legacy shifted?

Our churches are so different from where our forebearers’ were. For one thing, there were no megachurches coming out of enslavement. In the traditional church spaces that still exist, I do see some things that strengthen the working-class community. Encouraging young people to build their voices, for example. Churches are often the first place where young people speak, sing, or play an instrument. There’s encouragement for people to serve and lead. And to complicate ideas of who should be in leadership, it doesn’t matter if you’re a PhD or a postal worker. In traditional church spaces, those outside assumptions can melt away.

But the number of churches like that is decreasing over time because of the pull towards prosperity gospel— that preaches if God is blessing you, you’re wealthy, financially free, and successful. And that’s not where we come from as a people. The roots of Black Christianity are about believing that you are God’s chosen, in spite of the fact that you don’t have the worldly things people use to measure success. It was about the justice that you knew would come, if not in this life then the next.

To me, the prosperity gospel is anathema to thinking about holding up and supporting a Black working class. We face structural challenges that provide us with a world where most Black people are not going to be wealthy, and that shouldn’t make people think, well God doesn’t love me.

Do you believe Black churches are still radical spaces?

They can be. I belong to a traditional Black church. I’m in leadership and my husband is too. And I believe in Black institutions. I mean look at where I am. I’m a professor at UNC-Chapel Hill. This is an embattled space; it’s one of the roots of the affirmative action case. I’m here because it’s a state institution that admits Black students, working-class people, and students from rural communities who want the best education they can get in their home state. And I believe in that project.

I’ve been in all kinds of institutions that are problematic—Duke, UVA, NC State—and yet, I believed in the possibility of those institutions. So why in the hell would I not believe in the possibility of Black institutions? Why would I say Black institutions have flawed histories and should be disposed of? And then be in white institutions, that have flawed histories about my own people, and then say we can work it out! I believe we should inhabit Black spaces even when they are deeply imperfect.

Can the roots of the white working class be found in slavery as well?

Absolutely. The greatest trick ever played on the white working class was to get them to invest in a system that kept them poorer than they should have been. Slavery is a disinvestment in free-working people. If you’re just a regular white person with no land or enslaved people, this wasn’t a system you were able to double dutch your way into. Your wages would be suppressed by the existence of enslaved people. So, wealthy white people got poor white people to buy into some notion of race that would make them feel equal in status and as if everything was fine. I think that trick is still being played.

White working-class people need many of the same things as Black, Brown, and Asian working-class people do: health care, good schools, livable wages, higher education for their children. And yet people are still so invested in suppressing or being afraid of someone else that they aren’t really considering their own positionality.

Biden couldn’t have won without the Black working class. How has writing this book shaped your understanding of that group’s political priorities?

Recognition is key. What happened in Georgia is a great example of that. Stacey Abrams and a whole panoply of Black organizations went to places that traditional candidates rarely go to and made it clear that they wanted to hear from those communities. That was so powerful it changed the electoral map and what was possible in a state like Georgia.

The recognition of their existence and prioritizing the questions that they want to ask is important. If you go to different parts of the country, you’re going to get different answers. In some places, it’s environmental justice. Rural, working-class Black people live in some of the most toxic places in the world. If you’re in urban spaces, the decay and abandonment of cities are likely important. People want investment in their communities, safe places for their kids. They want education and a decent wage. They’re ready for the possibility of change, but it starts with the recognition of the particularities of their vulnerabilities.

This seems like a very pragmatic group of voters. Where do you think that pragmatism comes from?

There’s less focus on the particularities of the person representing you compared to what they actually get done. You can see that from a whole series of Black mayors who didn’t have the chops to get things done and were more invested in their own stuff. If there’s someone who knows how to get things done and can listen and understand how things work in their local communities, that’s what Black working-class voters care the most about. That’s what Biden represents. He was the most pragmatic-looking person in the previous election.

Your book reveals labor struggles that have rarely seen the light of day. I was so captivated by the post-Civil War strike waves set off by Black laundresses. Can you talk about Black domestic workers as a political force?

Tara Hunter’s book To ‘Joy My Freedom is an incredible account of the Atlanta Washerwomen’s Strike of 1881 when 3,000 of the city’s laundresses organized a union to demand better pay and labor conditions during the Atlanta Exposition. But that strike happened on a smaller scale everywhere.

Black washerwomen set the terms of their employment from the very first moment of emancipation. They refused to wash clothes on holidays. People wanted them to wash multiple loads in a week, to set the timelines for their work, and they said no. In 1865, Black washerwomen organized a union in Jackson, Mississippi. Who comes out of enslavement and organizes a union immediately? That tells you everything you need to know about who enslaved people were. It’s a reminder that workers don’t need someone to raise their consciousness. They don’t need someone to come teach them about what’s oppressive about what they do or the power they wield when they come together. They might need the resources of a union, but they damn sure don’t need directions.

What are some other major pivotal moments within Black working-class history?

I loved having the chance to write about the Pullman Porters and Black postal workers. They are that bridge between just working a job and making it a transformational collective enterprise. The Pullman Porters, like the washerwomen, could take advantage of the monopoly that they had on employment. George Mortimer Pullman wanted Black men to work on his sleeping cars. He pictured a sort of antebellum romantic version of travel would of course have a Black man servant waiting on you hand and foot. And those men became cosmopolitan leaders within the Black community, known for their mobility and knowledge. And when they formed a union, they used that platform to amplify demands from other workers.

The Pullman Porters powered the March on Washington movement, which started in the 1930s, and ultimately led to the 1963 March on Washington. Postal workers are the same. The first Black men who do postal service work are venerated Civil War veterans, and they had to fight hard against the myth of the Black male rapist just to deliver some mail and have a decent job. And many of them died. They were murdered by mobs in their effort to do postal work. That’s something we don’t think about. But their labor sets the groundwork for a civil rights generation that fights for access to federal jobs, which was a powerful counter to state-by-state segregation.

Do you think the demise of race-conscious admissions will affect the Black working class?

I have thought that affirmative action was going away my whole adult life—the argument against it has been so profound and hostile, and the ground on which most people discuss it is so a-historical. People talk about affirmative action like it’s just about diversity and wanting to see different-looking people in a room when it’s about historic exclusion. We’re in the middle of a complicated reparations discussion around the country. Affirmative action could have been thought of in those terms—but it’s gone.

The pathways that make it difficult to attend elite institutions are fraught and difficult for working-class communities because of the structural forces that make education unequal in this country. The things that tie the quality of education to housing and zip code. Those are fundamental injustices that, as a country, we are not interested in addressing. So, the narrow pipeline that pulls people out of under-resourced communities and into elite institutions just got narrower.

But as I said earlier, I believe in Black institutions. I am thankful that HBCUs still exist. I am hopeful that Black communities will begin to further invest in the experiences of HBCU students. I don’t think that there’s a legal means by which we can really contest this change, but I think enriching what the broader set of possibilities are for Black students should be the work.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.