This article is a collaboration between Mother Jones and Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit investigative newsroom. Also listen to Reveal’s accompanying podcast, “It’s Not Easy Going Green.”

Every day, thousands of tons of trash—rotten food, takeout containers, diapers, old shoes, construction debris, tires, plastic bags, soiled carpet, and lawn clippings—burst into flame and turn to ash and energy at an incinerator in Palm Beach County, Florida.

“Right there is probably about 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit,” said Ray Schauer, the facility operations director, looking at the incinerator’s combustion chamber during a tour in May. “Most people say, ‘If I could see hell, this is what it would look like.’”

As the trash burns, the municipal incinerator produces enough electricity to power about 45,000 homes and businesses. It also pumps out some of the same kinds of greenhouse gases and other pollutants as power plants that use fossil fuels. But because there’s always more garbage to feed the plant, the electricity it produces can be considered renewable.

That means the incinerator can also sell something more theoretical: renewable energy certificates, or RECs.

Each REC represents one megawatt-hour of renewable energy—enough electricity to power the average US home for a little over a month. But the energy itself isn’t what’s being bought and sold. Instead, REC purchasers—usually companies—buy the right to take credit for green power they’re not actually using. As a result, they lower their carbon emissions—at least on paper—and can keep using the same old fossil fuel-powered electricity.

In 2021, a New York City-based REC seller named Joe Barclay offered to buy the trash incinerator’s certificates for about 30 cents each.

Companies showcasing their green credentials usually wanted to buy Green-e certified RECs from wind turbines, which generate power without emissions, and could cost up to 20 times as much. But the trash incinerator RECs don’t meet any certification standard, Barclay told Schauer in an email, and hardly anyone wanted to buy them.

Barclay happened to know some buyers who would accept incinerator RECs, “and they are the only buyers that I’m aware of that can,” he wrote.

It wasn’t much, but it was easy money, so the Solid Waste Authority of Palm Beach County, which runs the incinerator, took the deal, and Barclay bought the RECs in bulk. Last year, he sold them for four times the original cost to his willing buyer: the United States government.

As the world teeters on the edge of climate calamity, this is how the federal government—the biggest energy consumer in the country—has been meeting its mandate to move away from fossil fuels.

Under the green veneer of the government’s renewable energy claims lie controversial, polluting power generators that expose the flaws and folly of the government’s reliance on RECs to pad its environmental stats.

Despite years of mounting evidence that RECs don’t help fight climate change, federal agencies have kept buying their way into compliance without changing the way they get the vast majority of their electricity.

As the Florida incinerator RECs demonstrate, it looks on paper like a win-win. Federal agencies can say they’ve gotten greener, and renewable energy producers get a bit of extra money for energy they were already producing. But with no change to the amount of greenhouse gases warming the Earth, the only loser in the transaction is the climate.

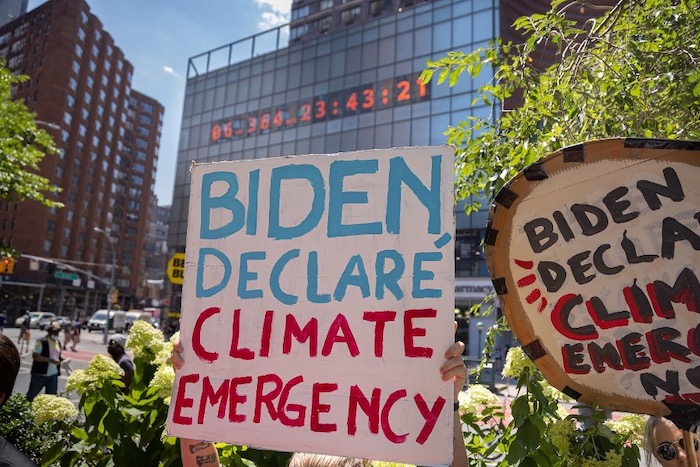

Activists rally near Manhattan’s “climate clock,” which shows how much time is left to limit global warming to 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels.

Michael Nigro/Sipa USA/AP

The federal government has enough buying power that it could lead the way to a broader, national transition to clean energy.

Instead, it has been leaning on RECs to meet modest environmental goals since a 2005 law signed by President George W. Bush required federal agencies to use 3 percent renewable energy. That figure rose to 7.5 percent in 2013 and hasn’t changed since. Any renewable electricity produced on federal land counts twice, as an incentive. But the law doesn’t mandate that agencies actually use renewable energy directly. So the government has relied for more than a decade on cheaper “unbundled” RECs that are sold separately from the electricity.

The Department of Energy said that in 2021, the most recent year for which data is available, the federal government outperformed the law, with 10 percent renewable electricity. But that number has little to do with how government buildings were actually powered.

Take out RECs, and that number goes down to 6 percent. And without the double-counting bonus, the total shrinks even more. The actual renewable electricity the government bought or generated that year amounted to just 3 percent.

In fact, RECs accounted for more than half of all the renewable energy the government claimed from 2010 to 2021, federal data shows. The government wouldn’t have met its mandate without RECs in any single year.

While most were from wind power, more than a quarter of RECs purchased came from biomass—energy produced by burning natural materials like wood and mulch, which can pollute the air in nearby communities. Another two percent came from trash incinerators. Fewer than one percent were from solar energy.

By filing dozens of Freedom of Information Act requests with federal agencies, Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting obtained many of the certificates the government uses to make its renewable energy claims, with details about the facilities where the RECs were produced.

In recent years, numerous federal agencies bought RECs from wood-burning biomass plants in rural Georgia communities, where residents complained of toxic pollution. They also bought RECs from a mill run by International Paper in Campti, Louisiana, that burns its own industrial byproduct to power the mill—in effect, subsidizing one of the world’s largest paper companies for something it was doing anyway.

A stormwater retention pond outlet at the Franklin Generation Biomass Facility releases “black effluent” into a tributary of Indian Creek in 2019, per regulators.

Georgia Department of Natural Resources

But it was in 2022 that agencies invested more heavily in incinerator RECs, which are less reputable than even controversial biomass RECs and are considered too dirty by the Environmental Protection Agency to be “green power.” The EPA spurns them in a program to encourage green initiatives at private companies because of the environmental impacts of burning non-natural materials like plastics.

Reveal requested detailed information from every federal agency that bought at least 10,000 RECs in 2021, including how much the RECs cost and where they came from. We received price details for a quarter of the government’s REC purchases, showing an average cost of just under $2 per REC. At that price, it would cost about $22 to cover the annual power use from the average US home.

President Joe Biden has ordered a dramatic change to how the government buys power, mandating 100 percent clean electricity by 2030 and making it harder for agencies to meet the target without meaningfully changing their practices. But as a far-off goal without congressional approval, it could fall apart if Biden is not reelected next year.

Crucially, the government would have to break its longstanding, frequent habit of choosing the cheapest way to look good on paper. That hasn’t happened yet. In fall 2022, nine months after Biden laid out his carbon-pollution-free plan, the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce and Energy, as well as NASA, the Air Force and the National Institutes of Health, spent at least $372,000 on hundreds of thousands of incinerator RECs.

The NIH spent almost $100,000 on RECs to call its North Carolina environmental health laboratory a “net-zero energy” campus, to show its “long-standing commitment to promote the health of the community and the planet.” More than two-thirds came from the paper mill and incinerator.

A spokesperson said the agency complies with government mandates and does not choose what kind of REC to purchase, though records show it had a variety of choices.

Tradable renewable energy certificates were first invented in the 1990s to put a price tag on greenness. Compared to fossil fuels, it was more expensive and less profitable for energy companies to build new wind and solar projects then. Selling certificates would bring in an extra revenue stream.

Plus, for other companies that wanted to go green, buying certificates was a much easier, more accessible way to get renewable energy. Corporate buyers could cut their carbon footprints without changing how they got electricity. So, in theory, the REC market would fund energy producers, signal demand for green power and incentivize the creation of more renewable energy.

The Environmental Protection Agency boosted the REC market by giving it the government’s stamp of approval and lavishing positive publicity and awards on companies that bought lots of RECs. The EPA even bought enough RECs in 2006 to call itself “the first federal agency to be powered 100 percent green.”

“At EPA, we don’t just talk the talk, we walk the walk,” said then-Administrator Stephen Johnson.

The idea behind RECs, though, was deflated years ago. The sales of cheap, unbundled RECs weren’t enough to stimulate investment in new renewable energy. News stories and academics blasted the concept as ineffective, creating a misleading sense of progress in cutting emissions and potentially distracting from more effective measures to fight climate change.

Major corporations like Google and Walmart decided against purchasing them. “RECs were cheap, and I think the adage ‘you get what you pay for’ applied,” Bill Weihl, the former green energy czar at Google, said in an email.

And yet despite the burgeoning noise of critics, the EPA remained a strong proponent of RECs, and federal agencies kept gobbling them up.

Meanwhile, scientists have been warning that the world is running out of time to avoid the worst ravages of climate change. Greenhouse gas emissions need to be cut nearly in half by 2030 in order to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Every fraction of a degree above that brings increasingly severe suffering: worsening heatwaves, fires, floods, storms, drought, and hunger.

At the Palm Beach County trash incinerator, claws grab garbage from a giant pit and transfer it to boilers, where it will be burned, generating electricity.

Solid Waste Authority of Palm Beach County

In Florida, the Solid Waste Authority of Palm Beach County brought its new $672 million incinerator online in 2015, over the objections of some residents, who worried about toxic pollution, and local environmentalists, who argued against burning trash at all.

The waste agency called it the cleanest, greenest, most advanced waste-to-energy facility in the world, with state-of-the-art pollution control technology that keeps emissions below EPA limits. Agency officials pointed to research that argues incinerators are better for the climate than landfills and had a study prepared that predicted no significant health effects to the local community.

Andrew Byrd of Riviera Beach says the government buying RECs from the incinerator isn’t helping the environment.

Najib Aminy

Andrew Byrd lives nearby in Riviera Beach, a historically Black city in Palm Beach County. He said he remembers sand dunes there when he was in elementary school. Now, there’s an industrial park, a power plant and, a short drive away, the incinerator. He worries about the fumes from burning garbage.

“It’s affecting the health of everyone,” Byrd said. “I could tell you a thousand ways you could have generated the same amount of power (other) than burning trash.”

He thinks the government buying RECs from the incinerator isn’t helping the environment. “The notion of selling RECs is a false economy,” Byrd said.

The Palm Beach incinerator emits hundreds of thousands of tons of carbon dioxide a year, and the synthetic materials in the trash alone release carbon at a similar rate to the national electric grid. Its rate of releasing other harmful gases—nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide—is even worse than an average gas-fueled power plant, though the waste agency argues this isn’t a fair comparison.

The incinerator was the latest, but not the only controversial plant where the federal government bought renewable energy certificates. In 2021, a half-dozen agencies purchased RECs from a pair of biomass plants owned by Georgia Renewable Power in neighboring rural counties in northeastern Georgia. The plants produced energy by burning wood chips, construction debris and, for a while, old railroad ties laced with the toxic chemical creosote.

After the plants started up in 2019, neighbors complained of stinging eyes, burning lungs, and the noxious smell of chemical fumes. Officials in Franklin County called it a public health emergency.

Georgia Renewable Power denied causing any harm. “We’re not emitting anything into the atmosphere that harms anyone,” president and chief operating officer Steve Dailey told a local TV station in 2020.

But state environmental regulators fined the company in 2020 for air pollution violations in Madison and Franklin counties and a toxic runoff into Indian Creek that potentially killed thousands of fish by one state estimate.

A fish collected in Indian Creek downstream of a tributary where a Georgia biomass facility released “black effluent” in 2019, according to state regulators. The company disputed that there was a widespread kill.

Georgia Department of Natural Resources

Federal agencies, including many that bought incinerator certificates, spent more than $700,000 on more than 400,000 of these RECs in 2021. They were generated in 2020, the same year local residents mounted a campaign that eventually won a state ban on burning railroad ties treated with creosote, which has been linked to cancer.

RECs from burning creosote-contaminated wood couldn’t be certified. Sonny Murphy, CEO of Sterling Planet, the company that sold the RECs, said the plants made assurances that the certificates were not tainted by creosote, but by then, they were too old to be certified. Luckily, the government didn’t mind.

“Most everybody would require certified,” Murphy said, “but the government does not.”

Another popular source of government-purchased RECs is called “black liquor,” a toxic byproduct of papermaking that mills have burned for decades to power their own operations. In 2020, federal agencies bought nearly 258,000 paper mill RECs—15 percent of all RECs for that year.

The agencies received certificates noting that for each black liquor REC, the facility produced about 4 pounds of smog-producing nitrogen oxide gas—a higher rate than an average coal plant. An International Paper spokesperson said in an email that the number on its certificates is an upper limit and its actual emissions are lower.

President Joe Biden signs the Democrats’ landmark climate change and health care bill at the White House in August 2022.

Susan Walsh/AP

As scientists raise alarms that drastic action is necessary to avoid widespread climate disaster, Congress hasn’t raised the Bush-era requirement that federal agencies use 7.5 percent renewable energy.

Over the years, though, the government’s overall energy use has declined and direct renewable energy use has increased, including from solar arrays on military bases. Governmentwide, from 2010 to 2021, direct renewable use increased from 1 percent to 3 percent of the government’s electricity demands.

Biden campaigned on a vow to eventually eliminate carbon emissions from the country’s power grid. But one of his most powerful proposals to do so—rewarding utilities if they phased out fossil fuels and penalizing them if they didn’t—died in Congress.

Democrats eventually pushed through the Inflation Reduction Act, which uses billions of dollars in tax incentives to stimulate green energy and is expected to dramatically cut emissions over time. But it won’t be enough by itself to meet Biden’s pledge under the Paris Agreement to cut US emissions in half by 2030.

Biden bypassed Congress when it came to the government’s own emissions with his 2021 executive order that federal agencies must use 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2030.

Agencies will still be able to use RECs, but under new restrictions. The order doesn’t include trash incinerators or biomass plants in its definition of carbon-pollution-free electricity. Half of the clean energy is supposed to be produced at the same time of day the federal government uses it—a strategy to push the grid to run cleanly at all hours. And the RECs have to come from the same region as the government agencies using electricity.

“This new requirement has accelerated the need for purchasing additional RECs,” said a spokesperson for the Department of Agriculture, adding that it will buy wind and solar RECs now.

There are some signs of progress. The Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory, which purchased the cheapest RECs available in past years, is planning to install a solar array at one of its sites and expects to hit the 100 percent clean energy mark early, without RECs, according to a spokesperson.

But previous sustainability mandates have failed from lack of funding, ineffective enforcement or leadership changes. Former President Barack Obama had ordered 30 percent renewable energy by 2025, but former President Donald Trump killed it and many other climate regulations when he came into office.

Andrew Mayock, Biden’s chief federal sustainability officer, is in charge of implementing the plan. In an interview, Mayock acknowledged that changes to the government’s renewable energy approach were necessary.

“We’ve made a number of pivots from a policy perspective from what was done under previous administrations, so that the federal government gets to a place of legitimately running on clean energy not solely from an accounting perspective,” he said. “The world was in a different place at that time as to the urgency and the need to get to carbon-free electricity.”

As for his progress, Mayock’s office pointed to a few agreements with utilities, to work on providing the required clean energy eventually.

“The shift to 100% carbon pollution-free electricity is already underway, and will continue to advance incrementally over the coming years through 2030,” his office said in a statement.

But a year and a half since the order was issued, the Biden administration hasn’t yet required agencies to set annual targets. Mayock’s office said it is working closely with agencies to help them develop plans.

Rep. Julia Brownley (D-Calif.) is pushing a bill that would codify a requirement for federal agencies to use 100 percent renewable energy, but not until 2050—20 years after Biden’s target. The 7.5 percent target in existing law is antiquated, and legislation is needed so that future presidents “do not backslide on this critical issue,” Brownley said in a statement.

Her bill, which has failed to advance in previous years, directs the government to use renewable energy produced on-site as much as possible. But it still allows agencies to rely on buying even more of the same kinds of cheap RECs.

“The government has a responsibility to the taxpayer to use federal funds wisely, but we also have responsibilities to future generations to fully and immediately address the climate impacts of our energy usage,” Brownley said.

Government agencies acknowledged often opting for whatever is cheapest.

The Defense Logistics Agency, which facilitates buying RECs for many federal agencies, picks contractors based on “Lowest Price Technically Acceptable,” according to a spokesperson. Federal agencies then chose that contractor’s cheapest option in 90 percent of the purchases coordinated by the logistics agency last year.

The Indian Health Service told Reveal that it purchases the cheapest RECs—including Georgia biomass and Louisiana paper mill RECs—to minimize the cost. Still, an agency spokesperson said: “The purchase of RECs incentivizes private industry to strive to create renewable/clean forms of electricity which is beneficial for the Earth’s environment.”

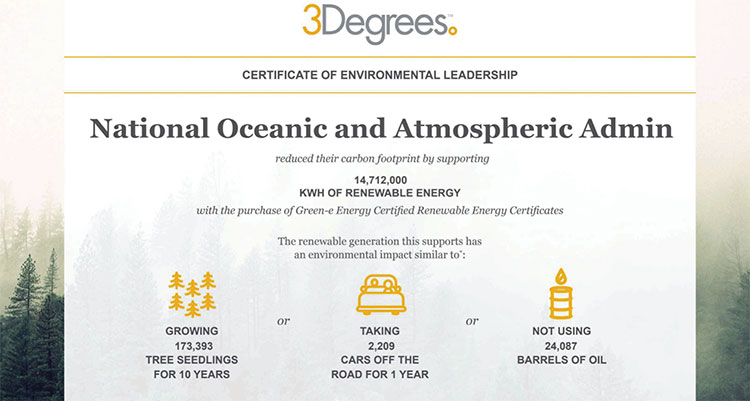

The certificates can come with laudatory titles like “Certificate of Environmental Leadership” or “Carbon Champion.”

NOAA

Some agencies—such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration—do prefer slightly costlier, certified RECs from solar energy or, more commonly, wind farms. Those certificates can come with laudatory titles like “Certificate of Environmental Leadership” or “Carbon Champion.” But compared to tax incentives and the revenue that energy companies get from selling the actual electricity, those RECs are also generally too cheap to have an impact, said Michael Gillenwater, executive director of the Greenhouse Gas Management Institute, who has published multiple studies critical of RECs.

In that sense, Gillenwater said, it doesn’t matter whether the REC comes from a wind farm or a trash incinerator. “It’s hard to have less effect than no effect,” he said.

Murphy, who runs Sterling Planet, the company that sold the Georgia biomass RECs to the government, said a more sophisticated way to support renewable energy is to invest early in a specific project to help it get off the ground. Buying whatever RECs are available on the open market, like the government does, is “easier to critique,” he said.

Alden Hathaway, a consultant and former executive for Sterling Planet, maintains that all RECs are beneficial, but in terms of creating new renewable energy, he said they “never made a huge difference.”

“We’ve always been talking about the value of the REC as something like the icing on the cake,” he said.

Buying the Florida incinerator RECs didn’t end up mattering much for the environment or the plant that produced them.

The Solid Waste Authority of Palm Beach County had been going about its business, turning garbage into energy for years without bothering with RECs. It only started selling them last year after being approached by REC sellers.

Ray Schauer, director of facility contract operations at the Solid Waste Authority of Palm Beach County.

Najib Aminy

So far, the waste agency is bringing in about $175,000 per year in extra revenue from the certificates. That amounts to less than 1 percent of the operating budget for the incinerator, said Schauer, the director of facility contract operations.

The money federal agencies spent on the incinerator RECs isn’t going to bankroll any new renewable energy. Most of it went to a middleman, the REC seller. What’s left helps make the trash bills a tiny bit cheaper for county residents.

By Schauer’s calculation, that $175,000 in revenue could save each homeowner about 18 cents on a nearly $180 annual trash bill. “It’s better than nothing,” he said.

Data reporter Melissa Lewis contributed to this story