Almost as soon as I get into the car, District Attorney Pamela Price makes it clear that she doesn’t want to talk to me, or at the very least she doesn’t have time to. “I have to get some stuff done,” she says politely, picking up her phone to dial a colleague as her driver steers the black Chevy Tahoe through traffic toward Oakland, California. Price is running late for an event, and it’s partly my fault: She left her last meeting without me and had to backtrack after her communications team reminded her that I was supposed to join the ride.

Price is tired of journalists. As one of the country’s most progressive district attorneys and the first Black woman to hold the position in Alameda County, she’s encountered extreme scrutiny since taking office in January 2023. She had campaigned to roll back mass incarceration, address racial disparities, and hold more police accountable, and won the race by a close margin, about 27,000 votes. But before she could unpack her boxes, critics launched an effort to recall her, funded primarily by a handful of wealthy hedge-fund and real estate investors. Price says they’re spreading misinformation to stoke people’s fears about crime, turning her into a scapegoat. And she thinks the media is amplifying their message, blaming her for social problems that existed long before she took office—problems that her predecessor did not seem to face nearly as much condemnation for. “There’s a double standard for progressive prosecutors,” she told me earlier. “No one was looking at the [prior] DA and saying, ‘What are you doing about this?’ Now, everyone’s looking.”

Price is among a cadre of progressive DAs who are challenging conventional political wisdom about crime and punishment. This “puts a unique target on their backs,” says Insha Rahman, who leads the justice advocacy group Vera Action. Since 2017, lawmakers in at least 17 states have introduced bills to remove power from democratically elected progressive prosecutors. In 2022, not long before Price took office, rich businessmen funded a successful recall of San Francisco DA Chesa Boudin. Now some of the same financiers are attacking Price. In early March, her opponents said they submitted more than the 73,195 signatures needed to trigger a recall election (though the signatures have yet to be verified). This time, they have the sympathies of a group of mothers of color who are grieving shootings and believe Price hasn’t punished the perpetrators harshly enough.

Price has, at times, shied away from correcting the record, wanting to focus instead on her job: prosecuting gun violence and robberies, looking into wrongful jail deaths, helping victims get services, hiring more diverse attorneys. “What does justice look like? That’s the job,” she says. “And that job is not going to change if we’re going through a crime wave or we’re not—I still have to do the job.”

But her determination to focus on the work instead of fighting rumors has created an information vacuum that her opponents have been more than happy to fill. Price is “willfully fomenting a culture of violence,” a press release for the recall campaign states: She has “a total lack of regard for public safety.” None of it, Price tells me, is true. But will she find a way to convince everyone?

As we drive into Oakland, I glance longingly at my list of unasked questions. To be fair, Price sat down with me for a 45-minute interview the day before, but I’d hoped to take the conversation further today, and she’s still looking out the window and talking on the phone. She’s wearing a bright turquoise dress, and every so often she looks down at a list of agenda items as she and her colleague run through plans to connect with more of her constituents at an upcoming event for foster kids.

Soon we arrive at Laney College, a community college in downtown Oakland where Price will talk with a roomful of students, teachers, and activists about the recall effort. “This is nothing more than a power grab,” she tells them, framing her struggle in the context of the civil rights movement. “For me to become your district attorney puts me in the most powerful seat in this county, and that makes some people nervous.” A few audience members murmur in agreement, a Pan-African flag draped on the wall behind them. “I am exactly where I am supposed to be,” Price adds, “so I need you all to help me stay.”

On a couch along the perimeter of the room, LaChe Graybill, a psychology student, listens with skepticism. Graybill had recently signed the recall petition after her daughter was assaulted in Oakland. A police officer claimed he couldn’t arrest the perpetrator because Price wouldn’t prosecute. She’d come to ask Price about it. “It was convincing, what she was saying,” Graybill said of the DA’s presentation. But “I don’t know how much of it is her trying to save her ass.”

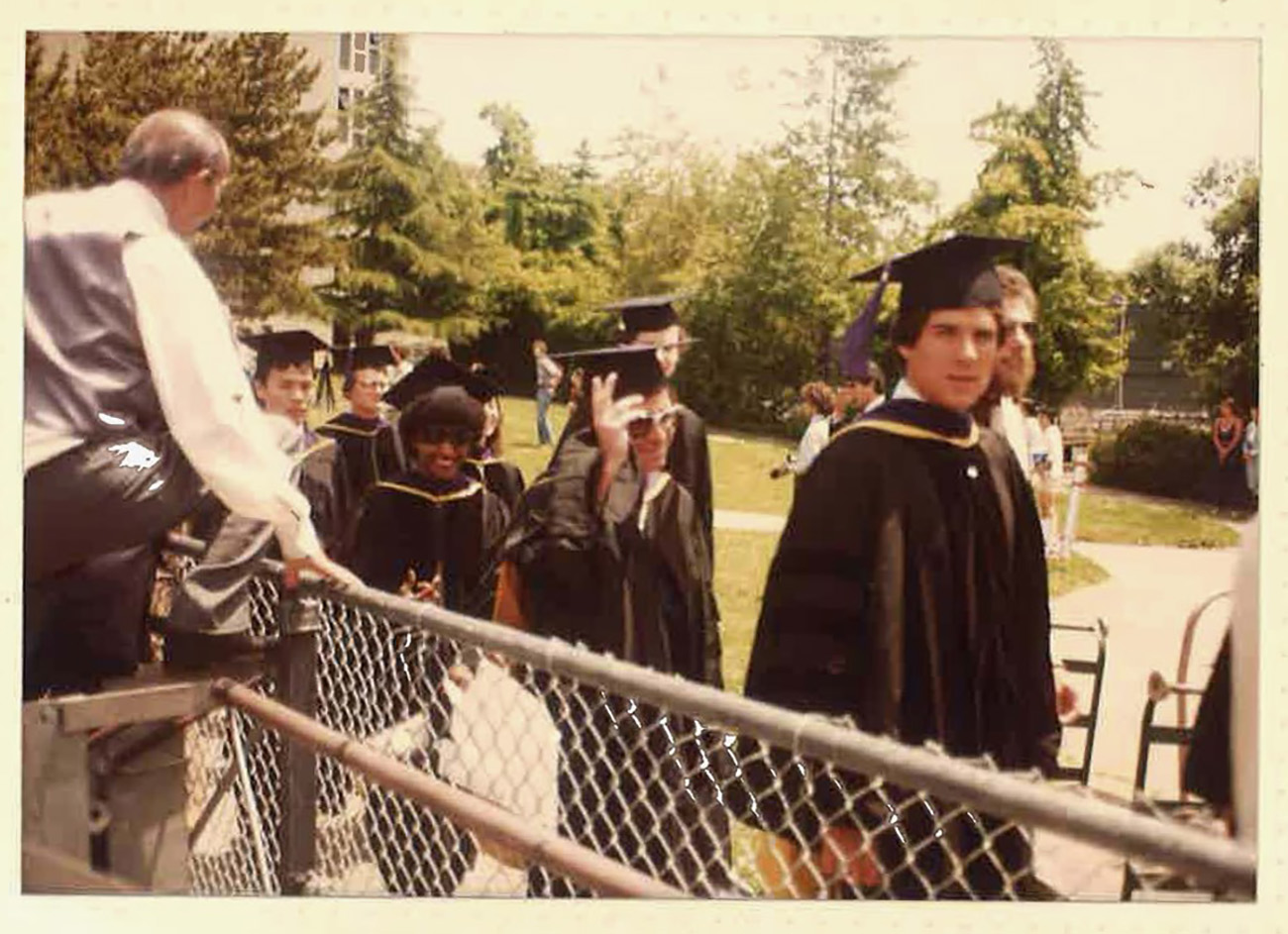

Price, standing right, with friends in 1975.

Courtesy Office of Pamela Price

One of the biggest misconceptions about Price is that she’s all or nothing—that she’s “lost sight of the real victims,” as her critics put it, because she’s “advocating for the accused.” But to understand Price, you must know that she sees this as a false dichotomy. It’s possible not only to care for both victim and accused, but to be both victim and accused. Just look at her own life.

Born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1956, as the civil rights movement was gaining steam, Price landed on the wrong side of the justice system before she could even drive. After Chicago police assassinated Black Panther leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, she was expelled from her college prep school for organizing a sit-in outside the principal’s office when she was 13. She ran away from home that year after her parents forbade her from joining more civil rights protests. The runaway Price ended up at juvenile hall, and then in foster care, before she was arrested again at another protest and spent a year incarcerated.

But through it all, Price had managed good grades, and she was soon admitted to Yale University with a full scholarship. There, she found herself on the other side of the justice system: Her senior year, she joined a lawsuit with a handful of female students who alleged they’d been sexually harassed on campus. Price testified that her professor gave her a C after she refused his sexual advances. The case made national news, the first time anyone had argued that sexual harassment violated Title IX, a federal anti-discrimination law. A judge ruled against the women, but the experience convinced Price to go to law school, where she again found herself in front of a court.

While studying law at the University of California, Berkeley, Price fell in love with a man who turned violent. But after she called Albany police repeatedly for help, the cops grew frustrated and arrested her for disorderly conduct. (She was acquitted.) Feeling jaded about criminal law, she left her job in public defense and later opened her own litigation practice in Oakland in 1991 to help other victims. She represented preteen sisters who were allegedly molested by a music teacher in Berkeley; worked with attorney John Burris to sue after BART police killed Oscar Grant in 2009; and successfully argued a racial discrimination case in front of the US Supreme Court. “It’s been a long time comin’,” she said after her client in that case won a settlement.

It wasn’t until 2017 that Price considered running for district attorney, at the encouragement of Yoel Haile at the ACLU of Northern California, who thought her experiences as a civil rights attorney and as a survivor of the juvenile justice system gave her “unique insight.” At first, Price hesitated at the idea of managing a prosecutors’ office with a reputation for harming people of color. The DA at the time, Nancy O’Malley, among other things, had repeatedly charged Black and brown children as adults. But since 2016, Price had watched other Black progressives become elected prosecutors in Chicago and St. Louis, drawn by the power to change the system from the inside.

Price had some political experience; she’d recently served on the Alameda County Democratic Central Committee. But running for chief prosecutor would be trickier. No one had challenged an incumbent in Alameda for nearly half a century; retiring DAs usually hand-picked a replacement, who then ran unopposed in the next election. With support from Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza and activist Angela Davis, Price won 43 percent of the vote in the 2018 primary, more than expected but not enough to beat O’Malley, who received tens of thousands of dollars from police unions. Price took the loss hard, says her friend Eloise Middleton, who campaigned with her. But she decided to run again, Middleton told me, after she heard John Lewis, the former congressman and civil rights hero, speak about the importance of “good trouble.”

By Price’s second campaign in 2022, the political situation had changed. O’Malley had announced her retirement without picking a replacement, leaving the field wide open. And the police murder of George Floyd in 2020 and the nationwide protests that followed had “pulled back the curtain on the broken system of criminal justice,” Price wrote to supporters in an email, “clearly exposing the racial, socioeconomic, and gender disparities.” She pledged a corporate-free, grassroots campaign, promising to charge more police, pursue alternatives to incarceration, and “restore public trust” by publishing demographic data about cases.

Across the Bay, another progressive DA was fighting to stay in office. In June 2022, several months before Price’s election, the city voted to recall Chesa Boudin. “A lot of us volunteers were quite worried that she couldn’t win in that environment,” says her friend Rivka Polatnick. But that November, Price won 53 percent of the vote to beat Terry Wiley, a more moderate candidate who’d worked for O’Malley.

Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price, center, takes part in a march to raise awareness of human trafficking in Oakland in January 2023.

Jane Tyska/Digital First Media/East Bay Times/Getty

Price’s historic victory complicated the story national tabloids tried to sell after Boudin’s ouster; it suggested that Bay Area voters still craved progressive justice reforms. “She is somebody who wants to correct the mistakes of the past,” says Nicole Lee, executive director of the Urban Peace Movement, a racial justice group. Her first month in office, Price reopened several cases involving police shootings and in-custody deaths, and she soon set up a commission to improve mental health courts.

But her promise to shake up the system, at a time when people were seeing more news coverage of crime, set the stage for a backlash. Within weeks she saw a post on the app Nextdoor falsely alleging that she’d bought televisions for the inmates at Santa Rita Jail. Other commenters were frustrated about plea deals that her office made for violent crimes, with punishments that they felt were too short. In February 2023, a Change.org petition began collecting signatures against Price, linking to some of these cases and claiming “she’s out of control.” In July, an official recall committee launched. When a recall campaign pops up that quickly, Boudin told me, “it’s clearly not about the policies or the management style,” but “about refusing to accept the outcome of the election” and making it hard for the DA to do her job.

Boudin’s recall was on her mind, but Price didn’t immediately worry. San Francisco had a much smaller proportion of Black voters than Oakland did, which meant Price might benefit from a broader base of support. And she had a longer history and deeper community roots in Alameda County than Boudin did in San Francisco.

But her location had downsides: While crime generally fell in San Francisco under Boudin, it had risen in Oakland before Price took office and was continuing to rise after her inauguration, especially homicides and thefts. “We are a place with people who have a lot of wealth in close proximity to people who are really struggling economically,” says the Urban Peace Movement’s Lee. The pandemic brought that into starker relief. For decades crime disproportionately affected low-income communities in Oakland’s flatlands, but now richer neighborhoods were seeing more instability too. “All of a sudden,” says Lee, “the alarm bells go off.”

When the Change.org petition against Price started in February 2023, Price didn’t give it much thought. She’d expected criticism, she told me, but she had bigger things to focus on than some online trolls. The office she’d inherited was a mess—literally, it needed to be cleaned, and attorneys were doing a lot of work on paper because the computer system was so antiquated. Complicating matters, many people in the agency had supported the campaign for Wiley, her opponent. (Some later accused her of firing them in retaliation; Price’s spokesperson told me the DA’s office does not comment on personnel matters.) “We were focused on the inside,” she told me. “We really weren’t paying attention to the people on the outside.”

But the dissenting voices outside were getting louder. A local ABC affiliate published an interview with a departing prosecutor who said people would die because of Price’s policies: “With each passing day, we’re receiving new information about plea deals that favor criminals and leave victims of violent crime feeling like they haven’t received justice,” wrote the reporter, Dan Noyes. (He failed to explain that around the country, about 95 percent of cases resolve in plea deals that don’t seek the maximum punishment.) “Everyone is in danger,” Oakland’s NAACP branch, which counts Wiley as a member, would soon claim, adding that Price’s “unwillingness to charge and prosecute people…created a heyday” for criminals. After Delonzo Logwood, who committed murder at age 18, received a plea deal from Price’s office in February 2023 that would cut his prison sentence to a fifth of what he’d been facing, Price got death threats.

Price at Yale graduation.

Courtesy Office of Pamela Price

Price’s supporters questioned why she wasn’t defending herself more. One of her top spokespeople, Ryan LaLonde, soon resigned because he wanted her to respond more to her opponents in the press, but she often refused to, unhappy that some reporters had disrespected her as a Black woman. “She really just wanted to do her job and not be drawn into it,” says her friend Polatnick. She shouldn’t be “raising a ruckus,” says Mister Phillips, an attorney in her office, “but there are people out there who are louder than her and they get press, and what they are saying is not always true.”

Sometimes Price was criticized for decisions she hadn’t even made yet. Last April, about 100 protesters gathered outside the county courthouse shouting, “Do your job!” and “Justice for Jasper!” In 2021, toddler Jasper Wu had been killed by a stray bullet in a gang battle on the freeway. Wu’s family worried Price wouldn’t punish the shooters harshly enough, especially after she instructed her office to limit the use of sentencing enhancements, a tool that can make prison sentences longer. At the time of the rally, Price’s office was still examining the evidence. “The coverage of her work has speculated on what she will do, in ways that haven’t proved to be her actual decisions,” says Cristine Soto DeBerry, founder of the Prosecutors Alliance of California, who describes Price’s policies as “measured” compared with those of other progressive DAs. “When discretion is vested in the hands of the first elected Black woman in the county, the spotlight and the magnifying glass is zeroed in more intensely.”

Ultimately, Price’s office did not make Jasper’s two alleged shooters eligible for life in prison without the possibility of parole, an option they’d faced under DA O’Malley. But the men did get charged with enhancements, and they are now facing 175 years to life in prison and 265 years to life.

There’s a general lack of public understanding about how DAs handle cases and the extent to which their policies do or don’t affect crime levels, Price tells me. “Everybody’s looking at me,” she says, “and they have no idea what I do. There’s so much about this position that has never been discussed.”

But Price’s reticence toward journalists is not helping her cause. At a public event I attended with her in Oakland, some people in the audience said they struggled to find good sources of information about the DA’s office. “Most of the news we get is from rumors,” an elderly man complained. More than a year into her term, Price still hasn’t fulfilled the San Francisco Chronicle’s request for charging data that could help voters see how her performance compares with her predecessor’s. Price says her team has lacked the technology to gather the data and is working to fix that. But David Loy, a legal director at the First Amendment coalition, told the Chronicle that her office appears to be violating the state’s public records law. “This is not behavior that seems consistent with an agency that wants to be transparent,” he said. “We have met and exceeded the parameters of the law with regard to our duty to assist the public,” agency officials wrote to the paper’s reporters in November.

Later that month, press-freedom advocates also raised alarm after Price’s office barred a Berkeley Scanner reporter, who’d published critical articles about the DA, from a press conference. (The office said the reporter’s media credentials were “under review,” but it later backtracked and invited her to future events after Loy alleged a First Amendment violation.)

When I emailed to ask about criticism that Price wasn’t open enough with press, spokesman William Fitzgerald said, “we’d push back on the premise of the question.” He referred to the time Price had spent with me for this story. “She’s not going to sit down with every single reporter because some of them have demonstrated…a one-sided view that doesn’t give a fair representation of what’s going on.”

Price has some reason to tread cautiously with journalists. Compared with traditional prosecutors, progressive DAs anecdotally appear to be held to a different standard in the press and on social media, says Pamela Mejia at the nonprofit Berkeley Media Studies Group. In the first year of the pandemic, the murder rate in Boudin’s San Francisco was roughly half that of Bakersfield, California, a Republican-led city with a more conservative DA. “Yet there is barely a whisper, let alone an outcry, over the stunning levels of murders” in Bakersfield, the think tank Third Way found in a study examining the outsize attention on crime in Democratic cities. “A lot of it is driven by police union and police department communication teams that are important sources for journalists,” says Boudin. His moderate replacement in San Francisco, DA Brooke Jenkins, has not received nearly the same amount of negative press as he did, even though overdoses and some crimes rose after she emboldened cops to crack down on drug sales. “Jenkins gets a pass partly because she talks about crime in binary terms that appeal to moderates and Republicans,” Chronicle columnist Justin Phillips wrote. “Price so far has proved incapable of doing this.”

The scrutiny on Price is exacerbated, says the Urban Peace Movement’s Lee, because of her race and gender, a trend that progressive DAs of color have seen nationally. Kim Gardner, the first Black circuit attorney in St. Louis, received letters calling her the n-word and a “cunt” before she resigned in 2023. Aramis Ayala, the first Black DA in Florida, got a noose in the mail after then-Gov. Rick Scott prohibited her from handling death penalty cases in 2017. In the Bay Area, recallers are also targeting Oakland Mayor Sheng Thao, who is Hmong American, and reformist Contra Costa DA Diana Becton, who is Black. “People feel very, very comfortable discrediting her,” Lee says of Price: “I have been called every kind of black B; I’ve been called a roach,” Price told me. “The attacks are vicious: There are no boundaries when it comes to Black women.”

“Everybody’s looking at me, and they have no idea what I do,” says Price, pictured in her office on Tuesday February 28, 2023. “There’s so much about this position that has never been discussed.”

Melina Mara/The Washington Post/Getty

So, who exactly is calling for Price’s removal? On a sunny Saturday in February, I go to meet some of her critics along the banks of Lake Merritt in downtown Oakland, where they’ve set up a table with hopes of enticing some of the joggers and dog-walkers circling the lake to sign their recall petition. The group is small, fewer than a dozen people, many of them women of color. Among them is Brenda Grisham, co-founder of the recall committee Save Alameda For Everyone (SAFE). Her 17-year-old son was shot dead outside their East Oakland home in 2010 as they were heading out to grab dinner at Burger King. Grisham wants Price to give victims’ relatives more input over prison sentences. But when she brought up her concerns at a meeting last April, she says Price didn’t take them seriously. She “feels she doesn’t have to talk with these families,” Grisham tells me. (Price says she meets with some relatives, but that her office served more than 12,000 victims last year, and that Marsy’s Law, which governs victim rights, does not require a district attorney to connect with everyone.)

Serena Morales, who helps Grisham with social media for the recall effort, lives in Hayward and worked previously on the campaign against Boudin in San Francisco. She tells me she’s upset that Price would not pursue sentencing enhancements for the men who killed toddler Jasper Wu—apparently having missed the news that Price’s team did, in fact, charge them with enhancements. When I ask Morales why enhancements are so important, she says she wanted to see the harshest possible punishment, and that enhancements might deter future crimes. “If these are gangbangers out on the street killing our children, what can we do to prevent that?”

Nearby are two mothers wearing T-shirts displaying photos of their dead children. Sophia, who asked that I not use her last name, says her five-year-old daughter, Eliyanah Crisostomo, was fatally shot on the freeway in 2023 while they were driving to a steakhouse in Fremont. In her case, Price’s office also pursued sentencing enhancements, but it took longer than Sophia expected. “Why did I have to wait nine months?” she asks. “Was it only approved because the DA is feeling the pressure of the recall?”

As I talk with the group, a white man on a bicycle peddles by and then stops, turning toward us. “You are all being paid by Trump voters!” he shouts at the mothers. Brenda Angulo, whose 15-year-old son, Erick Portillo, was shot in Hayward in 2023, asks the cyclist whether he ever lost a child. He responds coldly, asking whether hers died before Price’s election. “You’re lying,” he says after she refuses to answer. A white woman participating in a nearby Free Palestine protest comes over and intervenes, telling the cyclist that she, too, opposes the recall, but that he should move along. “Stop being a white asshole! You’re not helping our side,” she tells him.

Say what you will about his approach, the cyclist was hinting at a question on many people’s minds: whether the recall campaign is being steered by conservative forces. At the very least, some of the donors are rich. Campaign filings showed that about $1 out of every $3 spent on the recall last year came from a single hedge-fund partner, Philip Dreyfuss, who also spent heavily to oust Boudin. He and the next four biggest donors—real estate and tech investors Justin Osler, Isaac Abid, and Carl Bass, and real estate firm Holland Residential—gave about half of all the funds raised in 2023. As of early February, the recall campaign had spent $2.2 million, dwarfing Price’s resources. Much of the money went to SAFE, the group Grisham co-founded with Dreyfuss and Chinatown businessman Carl Chan, as well as to Dreyfuss’ second group, Supporters of Recall Pamela Price, primarily for signature gathering.

“We’re having a moment in California politics where wealthy donors can purchase a spot on the ballot and redo an election result,” says the Prosecutor Alliance’s DeBerry. She says that nationally, progressive DAs tend to do well at the polls. Philadelphia’s Larry Krasner, Chicago’s Kim Foxx, and St. Louis’ Kim Gardner were all reelected to second terms, as were dozens of other reformist prosecutors. Though Boudin remains one of the movement’s biggest losses, he actually had more supporters vote for him in the recall election than they did during his original election. “The progressive prosecutor movement is vibrant and strong because it’s advocating for changes that are popular with voters,” he told me recently. But those changes can rile up Republican politicians or rich business execs who were faring well under the status quo: “You end up getting pushback from above, not from below.”

In Alameda, I reached out to some of the recall campaign’s major donors, but most declined to comment. One of them, who asked that I not name him in the story, pushed back on the suggestion that the campaign was undemocratic or less legitimate just because it was funded by executives. “Many people, they’re as upset [with Price]—they just don’t have enough discretionary income to give to political campaigns,” he told me, adding that the recall petition garnered about 123,000 signatures. He said he got involved after noticing an uptick in crime in his neighborhood—he had two attempted break-ins at his house, one of his cars was stolen, and another one of his car’s windows were smashed five times. His friend a block over was held at gunpoint. “For the first 30 years I lived here, it didn’t feel that way. I never had it in the neighborhood, in front of the house,” he said. “People are legitimately concerned.”

The mothers at Lake Merritt told me they were volunteers, driven by a desire to feel safer and get accountability for their kids’ deaths. Sophia, whose five-year-old was killed by a bullet on the interstate, still can’t drive that route without an anxiety attack. “Justice needs to be served for my daughter,” she says, “and for all other innocent children that are dying senselessly.”

Over the past five years, polls show that Americans have grown more worried about crime, regardless of whether their cities have become more dangerous. Nationally, reported rates of violence “appear to be going down, but public perception is that people don’t feel safe and that data doesn’t necessarily feel meaningful for people,” says Mejia at the Berkeley Media Studies Group. She cited a phenomenon called the “mean world” syndrome: When people consume a lot of news about crime, they become convinced the world around them is a dangerous place.

In 2022, she says, news outlets published significantly more stories about violence in California than they did just five years earlier, mirroring national media trends. Journalists are writing more about crime, says Vera’s Rahman, in part because politicians are talking more about it; after New York City Mayor Eric Adams ran on a law-and-order platform in 2021, media mentions of the issue skyrocketed there, according to a Bloomberg analysis. In the Bay Area, relentless crime coverage adds to the unease some people feel when they see visible changes in their neighborhoods, after the pandemic amplified existing problems around poverty, substance abuse, and mental illness, leading to more homelessness and open-air drug use.

The fear creates a communications challenge for progressive DAs, says Mejia, because research shows that people process information differently when they’re afraid. If voters “are in an acute phase of anxiety, they might not be receptive to hearing the data points” or talking about solutions—“until there’s some acknowledgement that the fear exists,” she says. Rather than being idealistic or pretending bad things don’t happen, she says, it’s more effective to “give people space to feel heard in their anxiety and to move through it.”

“It’s really important to meet people where they’re at,” Boudin told me when I asked him what lessons he’d learned from the recall in San Francisco. “All of us post-Covid have a level of anxiety we never had before,” Price says, “so there is fear, and it’s legitimate fear, and I have to acknowledge that.”

After turning away from the press during her early days in office, Price says she’s thinking more now about how to talk with the public. In February, she invited me to a video call with the communications team from her Protect the Win campaign, which is fighting the recall. They discussed the latest negative media coverage, this time about Gov. Gavin Newsom’s decision to send state attorneys to help Alameda prosecutors with some cases. They’re “saying the DA’s office is in soft receivership,” Fitzgerald, her campaign spokesman, said. Price laughed at the falsehood. “We laugh,” he added, “but when we know people have bought their lies, it’s because of that type of story.”

“I get it,” she said. They’re trying to say “the DA’s office is a hot mess. So what’s the opposite?” She listed some accomplishments to share with people, like building up the collaborative courts, tackling the backlog for victim services, and hiring more attorneys of color. “This is the most diverse district attorney’s office in the whole state,” she told me later. “We have done a lot to bring people in who reside in this community, who were raised here, who want to serve this community, that look like the community.”

Hoping to reach an even broader audience, Price also hosts events where Alameda County residents can ask her questions, using the gatherings as an opportunity to dispel misinformation. At an event at the Oakland Asian Cultural Center in February, she asked the crowd, “How many of you have heard that I did not charge the two men accused of killing toddler Jasper Wu?” A handful of folks raised their hands. She held up a pamphlet that her communications team distributed, with information about the case. “This is an opportunity for you to hear the facts for yourself,” she said.

A KQED reporter raised her hand and said people were getting misinformation from police officers, too. “We’ve been hearing that—it’s obviously a concern of ours,” responded Oakland Assistant Police Chief Tony Jones, who was seated beside Price. “When we hear that our officers are making comments like that, it’s very disappointing to us.”

Back at Laney College, Price wraps up her speech and takes some questions from the audience. She calls on LaChe Graybill, the psychology student who signed the recall petition. Graybill asks about the Oakland cop who claimed he couldn’t arrest her daughter’s assaulter because the district attorney—Price—wouldn’t charge him. Price’s first instinct is to debunk the police officer’s claim, but then she changes her tactic. “I’m sorry about what happened to your daughter,” she tells Graybill, her voice softening. “We are living in a terrible time where people don’t care, and they will hurt you. We have to try to protect ourselves, but sometimes we can’t.”

Price continues talking about another question Graybill raised, about why her daughter was still waiting for victim assistance funds from the DA’s office several months after the attack. Price explains that before she inherited the job, a backlog had pushed wait times to more than a year. Her team had since gotten it down to 59 days—“which is still not acceptable,” she says—and her goal was to make sure victims received assistance within 10 days. One of Price’s colleagues walks over to Graybill and gives her a business card, urging her to call. “The system is broken—that’s why I’m here,” Price tells her. “It’s broken.”

Recent polling by Rahman’s Vera Action asked voters in California and nationwide what approach they wanted to see from DAs. Most said they wanted prosecutors to focus on preventing crime, and to prioritize “justice and the truth.” “Not to necessarily seek a conviction, and not to necessarily engage in reform,” says Rahman, but “to advance a fair process.” They don’t need prosecutors to use “tough on crime” rhetoric, she adds, “but they do need you to signal that you’re serious about safety.”

After the Laney College event concludes, Price slips out the door and I run to catch up, but she tells me I can’t tag along anymore because she has too much work to do. Instead, I go back to the room to find Graybill. She tells me that by the end of Price’s talk, she no longer wanted to support the recall; she even removed her signature from the petition. I wonder what changed her mind. “Her willingness to hear,” she tells me of Price. “She answered the question in detail, instead of brushing it off.”

If the district attorney is going to survive to the end of her term, she’ll need to do more than convince a single voter. Price may no longer be able to choose between keeping her head down to focus on delivering justice, or taking time to talk with people about it. Both are the job now.

Update, April 17, 2024: Alameda County officials have finished counting signatures—and confirmed that District Attorney Pamela Price will face a recall election later this year. It was a close call: Price’s opponents needed 73,195 valid signatures to force an election, and they got 74,757.