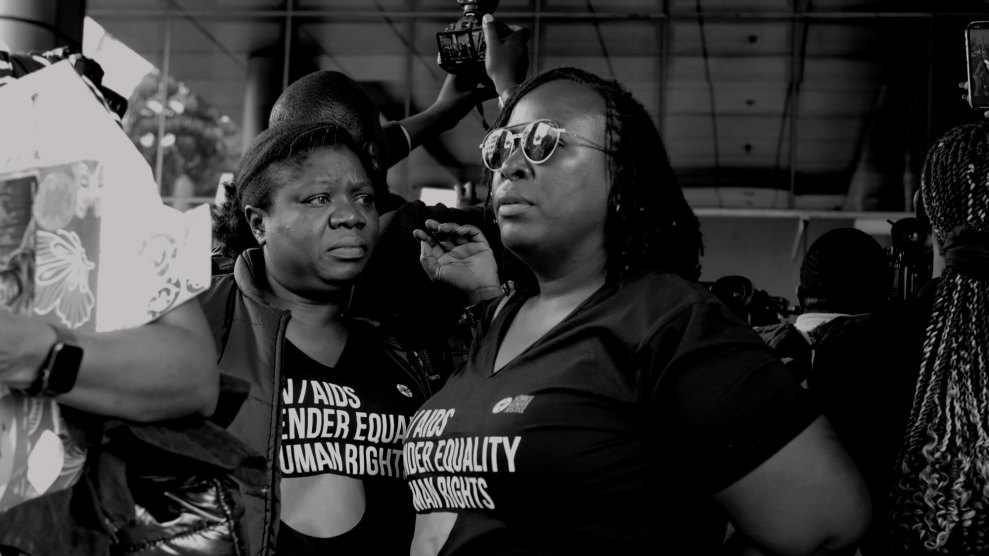

Human rights activists stand outside the constitutional court in Kampala, Uganda.Hajarah Nalwadda/AP

The ripple effects of Dobbs continue to emerge in unexpected places—and to threaten other civil liberties.

Yesterday, Uganda’s constitutional court, the country’s second-highest judicial body, cited the US Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade in its ruling to uphold the majority of a sweeping anti-gay law that criminalizes homosexuality and same-sex marriage, and allows for convictions of up to life in prison and the death penalty in some cases.

The court wrote that Dobbs constitutes a recent development “in human rights jurisprudence…where the Court considered the nation’s history and traditions, as well as the dictates of democracy and rule of law, to over-rule the broader right to individual autonomy.”

In the ruling, which came after the challenges to the “Anti-Homosexuality Act” passed by President Yoweri Museveni last year, the court repealed certain sections of the law, including those that criminalized renting property to LGBTQ people and mandated reporting “acts of homosexuality” to police.

But the fact that the court upheld most of the law obviously amounts to a massive setback for LGBTQ Ugandans—and offers a striking look at how Dobbs might be marshaled to restrict other rights both in the US and around the world.

“We have been saying in the United States that the decision in Dobbs could easily be extended to the context of personal liberties, like the choice to engage in sex with a person of the same sex, to marry a person of the same sex, to use contraception,” Melissa Murray, a professor at New York University’s School of Law and a leading legal expert on reproductive rights and justice, told me. “The fact that a high court in another country used it in that way suggests how easily it might be deployed in our country for the same thing.”

“Folks in this country ought to take a page out of it—this is really alarming,” she added.

The UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights, Volker Türk, condemned the high court’s ruling in a statement yesterday, noting that nearly 600 people “have been subjected to human rights violations and abuses” based on gender identity or sexual orientation since the law took effect last year. The law, Türk said, “must be repealed in its entirety or unfortunately this number will only rise,” adding that it was also contrary to “Uganda’s own constitution and international human rights treaty obligations.” Amnesty International also notes that, since the law passed, there have also been more than 250 evictions of people suspected to be LGBTQ or to associate with LGBTQ people, and more than 200 “other cases of actual or threatened violence.”

Human Rights Watch called the law “abusive” and “radical,” alleging that it “further entrenches discrimination against [LGBTQ] people, and makes them prone to more violence.” National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said it’s “deeply disappointing, imperils human rights, and jeopardizes economic prosperity for all Ugandans.” And Secretary of State Antony Blinken said the country’s “international reputation and ability to increase foreign investment depend on equality under the law.” (Homosexuality is criminalized in more than 30 of Africa’s 54 countries, the Associated Press reports.)

This is, of course, not the first time that Dobbs has been used to restrict rights beyond abortion access—including here at home. Dobbs was cited throughout the Alabama Supreme Court decision last month that effectively banned IVF procedures. (The Alabama Legislature subsequently passed a bill, which the governor signed, to protect IVF access, but it didn’t address the legal status of frozen embryos.) And Justice Clarence Thomas used the Dobbs decision to call for the court to revoke the rights to marriage equality, intimate sexual relationships, and contraception, all of which he called “demonstrably erroneous.”

Dobbs has also been cited by anti-abortion activists seeking to roll back legal rights in Kenya, Nigeria, and India, according to research compiled by the advocacy organization Fòs Feminista. Globally, though, most countries have actually liberalized their abortion laws over the past few decades, with only four—the U.S., Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Poland—restricting them, according to the Center for Reproductive Rights. And last month, France became the only country to explicitly guarantee a right to abortion in its constitution, which President Emmanuel Macron and other French lawmakers promised to prioritize just hours after the Dobbs ruling dropped in June 2022.

The fact that the US rollback of abortion rights could give rise to both France’s protection of them and Uganda’s elimination of LGBTQ rights, Murray said, shows that Dobbs “is viewed as authoritarian”: Its power, in other words, lies in the hands of whoever gets to interpret—or resist—it.