This story is a partnership with the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit investigative reporting news organization.

It wasn’t a difficult choice for Linda Evers, after graduating high school in 1976, to take a job crushing dirt for the Kerr McGee uranium mill, just north of her hometown Grants, New Mexico. Most gigs in town paid $1.75 an hour. This one offered $9 an hour.

She spent seven years working in New Mexico’s uranium mines and mills, driving a truck and loading the ore crusher for much of the late 1970s and early ’80s, including through her pregnancies with each of her children. “When I told them I was pregnant,” Evers, now 66, recalled, “they told me it was okay, I could work until my belly wouldn’t let me reach the conveyor belts anymore.”

Both children were born with health defects—her son with a muscle wrapped around the bottom of his stomach and her daughter without hips. Today, Evers herself suffers from scarring lungs, a degenerative bone and joint disease, and multiple skin rashes. All of which doctors have attributed to radiation exposure.

“We never learned about uranium exposure or any of that. They were killing us. And they knew they were killing us.”

“We never learned about uranium exposure or any of that,” said Evers, who recalled safety training that consisted primarily of standard first aid such as treating burns and broken bones. Only decades later Evers learned of the health risks she’d incurred. “They were killing us. And they knew they were killing us.”

American workers have labored in uranium mines since the early 1900s, with the majority of mining occurring from the 1950s through the end of the Cold War, when tens of thousands of workers produced hundreds of millions of pounds of uranium. The government has since acknowledged that, despite being at least partially aware of the health risks, decades of miners like Evers were allowed to labor in dangerous conditions.

“Anything that got in the way of producing more nuclear weapons, testing more nuclear weapons, anything that made that more expensive was to be avoided if at all possible,” said Stephen Schwartz, senior fellow at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

In 1990, Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, creating a process by which some of those harmed as a result of the expansion of the US nuclear program could receive financial and medical benefits. “The bill in a small way will make up for the mistakes made in the early days of the uranium mines,” Sen. Pete Domenici (R-N.M.) said during a public hearing in March 1990. More than 500 members of the Navajo Nation who either themselves worked in or had loved ones who worked in uranium mines attended, according to an account in the Arizona Daily Sun. “We could never replace the ones that died or those who are ill,” he continued. “But this is a giant step.”

In the three and a half decades since, 41,977 Americans have received about $2.7 billion—roughly $62,000 per—for health impacts caused prior to 1971 when the US government stopped being the sole domestic purchaser of uranium.

Advocates across the country have long argued that such benefits are available to far too few people given that the US continued to operate uranium mines and employ miners for years after 1971 and that medical advances have provided new insight into the adverse health effects for many others—such as those who lived downwind of test sites or in homes constructed near or on top of nuclear waste.

“That was a problem—this person got compensated, this one didn’t,” said Doug Brugge, an expert in health epidemiology related to uranium mining. “For people who are not government bureaucrats or academic intellectuals and parsing numbers, it just felt really unfair.”

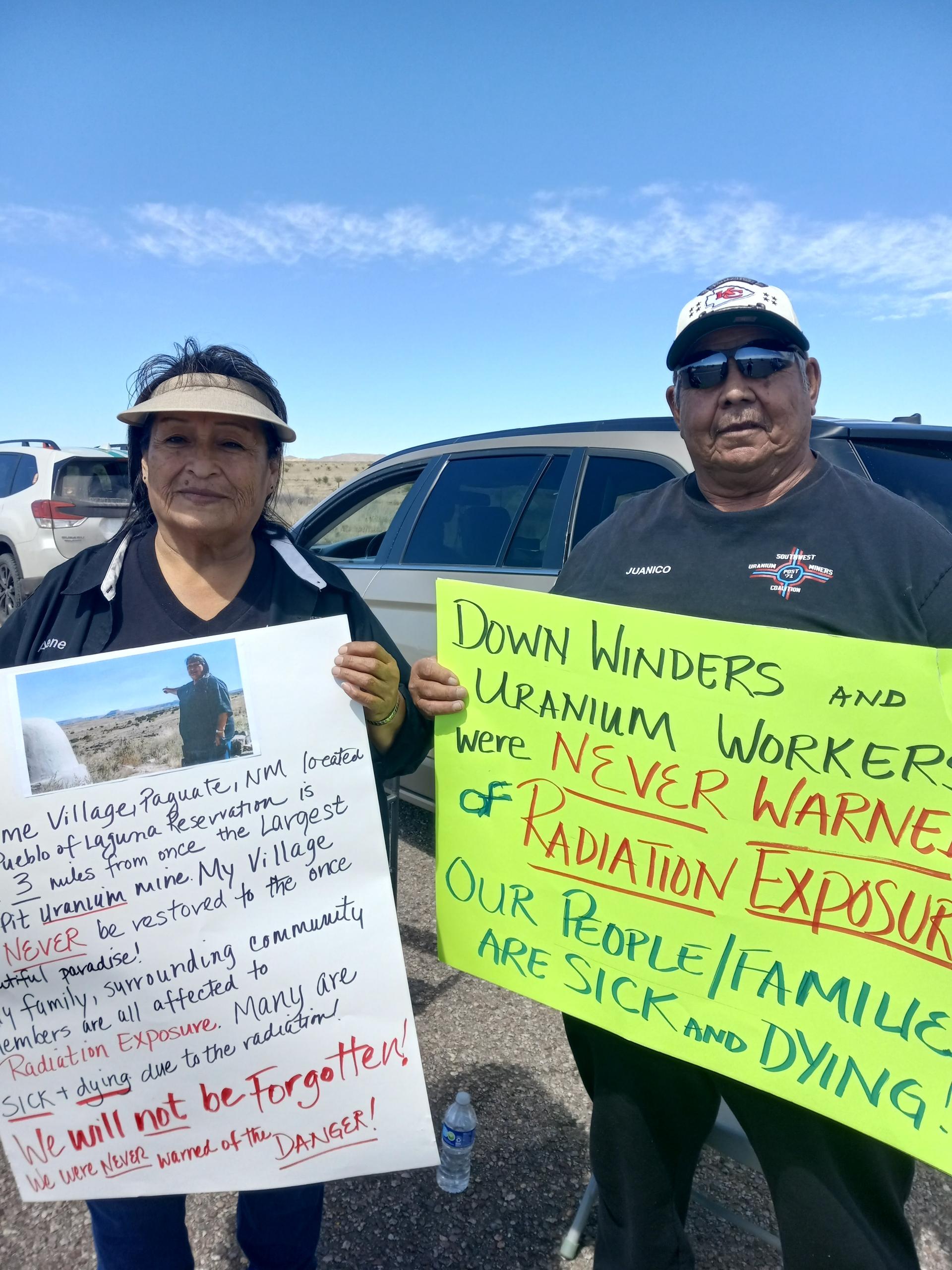

Arlene Juanico and her husband Lawrence both worked as post-71 uranium miners, making them among those ineligible for RECA benefits under the original legislation. She remembers being hired within a week of having applied, given a hard hat, leather gloves, and ear plugs but never warned about the danger of radiation. Today their home in Paguate, New Mexico, sits in the shadow of Jackpile uranium mine, an EPA Superfund site. The Juanicos say that they wake each morning to a strong, rotting scent wafting off of the vacated mine. “Lawrence and I never considered being exposed until 2019,” she said. “We breathed that air 24 hours a day.”

Within the last year, Lawrence has been diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis, the same disease his father and uncle—who worked the same mines—died from. Arlene fears she’ll be next.

With RECA benefits scheduled to expire earlier this year, a bipartisan set of lawmakers proposed a significant expansion of the program which, among other things, would have extended the program until 2030 and increased the compensation amount and eligible circumstances to now include people in about a dozen states, including people like Evers and the Juanicos.

The proposal passed the Senate, but died at the doors of the House when Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.)—despite pressure from lawmakers on both sides of the aisle—refused to bring it up for a vote. The Senate bill had a two-thirds majority in the Senate, and 20 of 47 Republican senators voted in favor. However, from Johnson’s perspective, the issue was the cost of the expansion’s more than $50 billion price tag without budget offsets, and he did not believe the Senate bill had majority GOP support in the House, according to a Republican leadership aide.

The result: For the first time in 34 years, Americans who suffer due to radiation exposure have no pathway to federal compensation.

“It’s really tough to have people say, ‘Nope, sorry that’s too expensive,’” Tona Henderson, director of Idaho Downwinders, said through tears. “’It wasn’t too expensive to poison you, but it’s too expensive to fix what we did and you aren’t worth it.’”

“It’s really tough to have people say, ‘Nope, sorry that’s too expensive. It wasn’t too expensive to poison you, but it’s too expensive to fix what we did and you aren’t worth it.’”

Henderson and other advocates still hope they will be able to convince Johnson to allow a vote between now and the end of the year in order to send the program to President Biden, who has said he supports the legislation.

“We have a very short window to try to convince people that this needs to be taken up,” Henderson said. “We’ve been told that we have the votes in the House, that we just need Speaker Johnson to bring it to the floor.”

The roadblock in the House has frustrated the bill’s Senate sponsors, some of whom note that 57 of the places whose residents would benefit from the RECA expansion are in GOP districts. Sen. Ben Ray Luján (D-N.M.) said that Johnson’s “inaction puts the lives and well-being of our constituents at risk.” Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) has vowed to attach the RECA expansion to any legislation that moves through the Senate.

“As I stand here on this floor, Coldwater Creek: still poisoned. The Westlake landfill: still burning. Weldon Spring: not cleaned up. Government hasn’t done anything,” Hawley (R-Mo.) declared from the Senate floor earlier this year. “The victims have waited too long.”

Those living near St. Louis are within a few mile radius of two Environmental Protection Agency Superfund sites—Coldwater Creek and Westlake landfill—which is a program designed to clean up some of the nation’s most contaminated land.

Last year, the Missouri Independent, MuckRock, and the Associated Press published a trove of 15,000 documents showing that officials in St. Louis were aware as early as 1949 of the danger presented by the radiation waste produced in the city.

Among those who would benefit are Dawn Chapman, who as a 12-week pregnant newlywed moved to an idyllic suburb on the outskirts of St. Louis in 2000 without ever considering that it would harm her family’s health. “We really thought we hit the jackpot,” she said.

Now, Chapman’s husband is chronically ill and her 18-year-old son was diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes and is in limbo with an additional unknown chronic illness. Doctors have told Chapman’s family that their health woes are likely the result of radiation exposure from the landfill, which sits a couple of miles from their home.

“It’s devastating,” Chapman said. “We feel guilty, we feel like we did this to my son, our kids, it’s our fault.”

The nuclear waste is primarily residue from downtown St. Louis’ Mallinckrodt Chemical plant, which was one of the largest producers of uranium oxide and uranium metal for US atomic bomb testing from 1942 to 1957. The nuclear waste was illegally dumped in the landfill in the early 70s. By 1988, the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission had documented a “significant increase in the radiological hazards,” noting, among other things, groundwater contamination and that some of the radioactive waste had no soil cover.

In 1990, the EPA declared it a Superfund site and has worked to prevent further contamination, with a full plan for remedial design expected to be complete sometime this fall, according to an EPA Region 7 spokesperson. After the final plan is approved, the EPA will enter into an agreement with those responsible to start the cleanup process. For the West Lake Landfill Superfund site, the US Department of Energy, Cotter Corporation, and Bridgeton Landfill are the “potentially responsible parties” as determined by the EPA, so work will begin at the Superfund site once the three parties enter a consent agreement with the agency.

Without access to RECA benefits, Chapman said her family has had to spread out medical treatment over the course of the year. She worries what will happen if she, too, becomes sick.

“I almost feel like that’s the game being played against us by the Speaker,” said Chapman, who helped launch Just Moms STL, a nonprofit that advocates for those suffering from radiation exposure in their local community. “We have to go back and educate all these other elected officials on what happened in St. Louis, because they don’t know. We’re left out.”

Reuters recently published an investigation diving into how a federal health agency failed a neighborhood near Chapman, also ailing from radiation exposure.

It’s a similar story in Idaho, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and Utah, where communities that sit downwind of former nuclear testing sites have been ravaged by cancers and other diseases yet excluded from RECA benefits for decades.

Tina Cordova has lost count of all the relatives who have died from various cancers and chronic illnesses in the past several decades. She herself has been in remission from thyroid cancer for 26 years and is the fourth generation of five in her family to have had cancer over the past century. At least a seventh-generation New Mexican, Cordova’s hometown of Tularosa sits about 45 miles downwind from where the Trinity atomic bomb was detonated in 1945.

“It’s affected everybody in my family one way or the other,” said Cordova, 64, who has spent years collecting roughly 1,200 testimonials and health surveys from New Mexico families who believe they have suffered radiation exposure. “We just trudge through this and we wonder who’s going to be next.”

In her years traveling around the state to advocate for those suffering from radiation exposure, Cordova has heard the same story on repeat. First, people get sick from radiation exposure and have to quit their jobs. When they lose their health insurance, they have trouble keeping up with their medical bills and the travel required for treatment. At some point, they face a choice: either leave their families with hundreds of thousands of dollars in medical debt, or go home to die.

Under the proposed RECA expansion, residents downwind of the Trinity test site would be able to receive up to $100,000 for medical bills or to travel for treatments, as well as access to additional medical benefits. In the meantime, they aren’t eligible.

“We’ve been irreparably harmed and they recklessly did it. And now when we’re trying to have them atone for this, for them to say it’s going to cost too much is absolutely unacceptable,” Cordova said. “It speaks to how much they had to dehumanize us to do this. They didn’t treat us like human beings, they treated us like collateral damage.”