Trump endorsing the opponent is not great news!Vasha Hunt/AP

Tommy Tuberville describes himself in a tumble of Cs: “Christian,” “Conservative,” “Coach.” This alliterative bit is a catchy slogan for the political outsider and former head coach of the Auburn Tigers football team who last week forced a somewhat surprising runoff against former Attorney General Jeff Sessions. On March 31, the two will compete to be Alabama’s Republican nominee for the Senate, vying for the seat that Sessions held for 20 years and is now occupied by Democrat Doug Jones.

Tuberville came out on top last week in the sprawling field, besting Sessions, as well as Rep. Bradley Byrne and Roy Moore, but still came short of a majority needed to clinch the nomination.

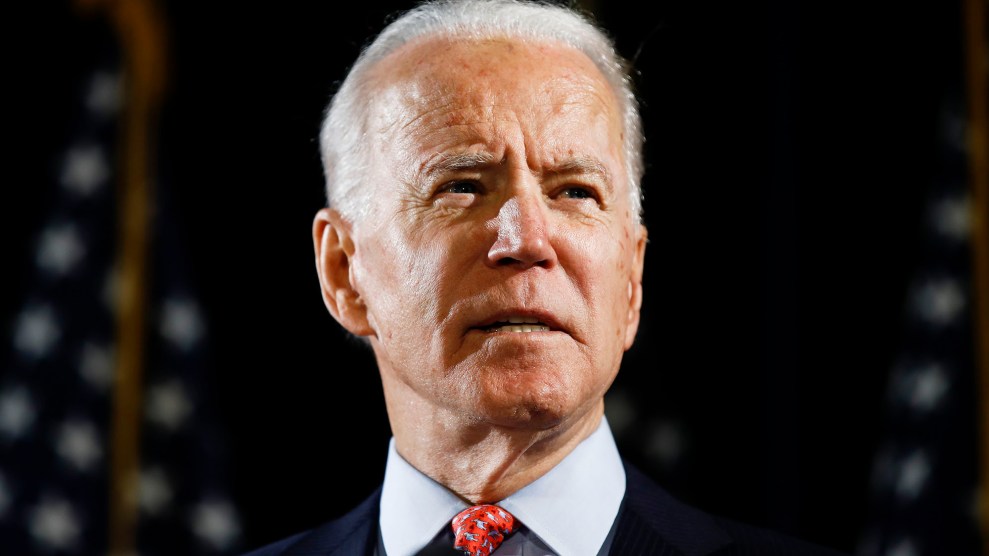

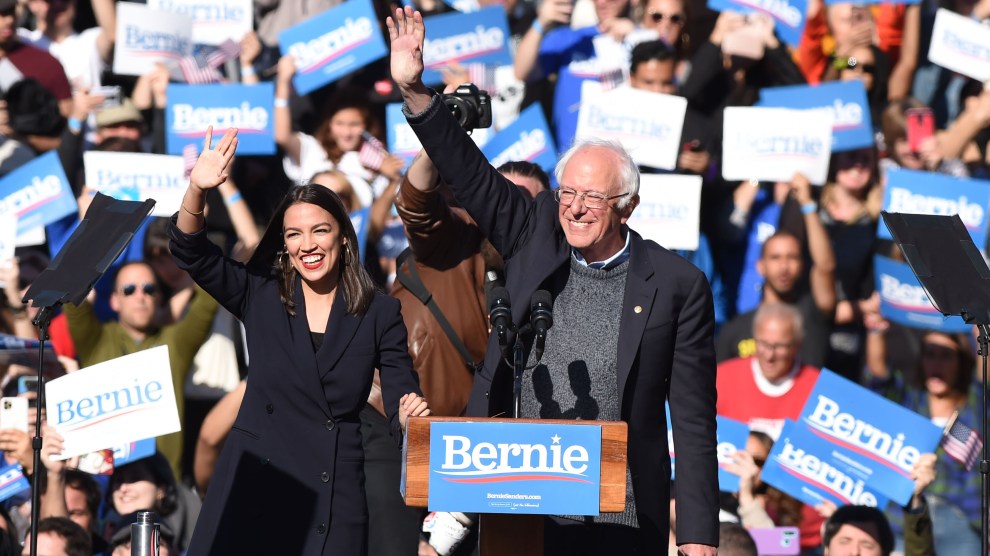

Then, last night, he won the real prize: President Trump’s endorsement.

While the endorsement is a somewhat juicy piece of political theater, it’s too simplistic to consider it a pure act of vengeance against Trump’s former confidante (although, of course, Trump does love a good grudge). Tuberville is no chump here; he is in many ways the model Trump candidate.

Back in 2017, Jones took Alabama by sheer force of Republican fuck-ups; as my colleague Pema Levy wrote at the time, “Republicans managed to screw everything up.” So it might be confusing that Alabamans, and even the president, would risk anything but steady Sessions. Tuberville has never held public office. He’s never even donated to a federal campaign, according to FEC data. He is so inexperienced—as Jason Zengerle noted in a piece over at New York Times Magazine—that several months ago Republicans worried Tuberville could very well lose to Jones (this would be a Democrat winning in Alabama—twice!), prompting politicos to bug Sessions to jump into the race in the first place.

But here’s the key context: As I’ve written previously Tuberville has a folksy Trumpism, spanning a long career as a coach, which he parlayed into sports radio spots that appealed to a GOP electorate that doesn’t mind the demonization of abortion, communists, and the 1960s, mixed with a bit of football analysis. He then built on that base with campaign ads featuring him either on a football field or in an actual field, with a gun. When Sessions entered the race in November last year, the primary devolved into a battle for who can pledge fealty to Trump more convincingly. Tuberville has excelled there, too. His ads hit simple Trump talking points: “Build The Wall,” “open borders,” “socialists.” His campaign has happily focused (almost exclusively) on his love for Trump, serving up policy only when it means talking about the greatness of Our Dear President. Tuberville’s history of spewing birtherism and xenophobia are played as advantages. And telling someone they’re divine helps, too. “God sent us Donald Trump,” Tuberville informs the camera in one ad. “Because God knew we were in trouble.”

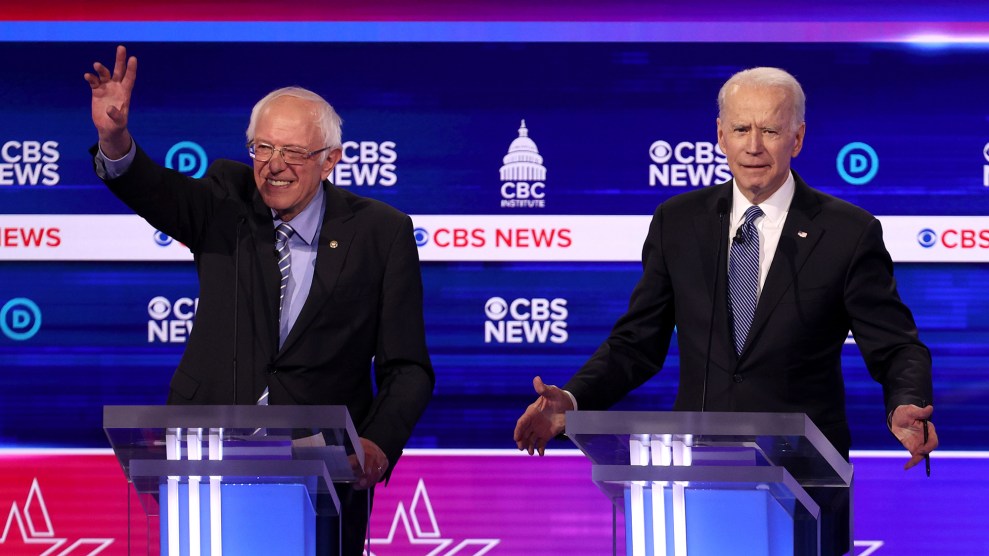

Sessions famously has a more complicated relationship with the president, to say the least. The first senator to endorse Trump, Sessions was picked as attorney general, then recused himself from the investigation into Russia and, finally, resigned after months of attacks from Trump. He’s now hated by the White House, a punching bag. Though in a bit of restraint—Alabama, after all, is critical to guaranteeing Republicans’ Senate majority—Trump didn’t declare a clear choice in the race until after the first round of voting. But you could feel it coming. He couldn’t help but gloat at Sessions’ inability to win back his seat without a run-off.

The nativist platform that Sessions built and that (unfortunately) worked for decades in Alabama evolved as Trump adopted it. These ideas have succeeded throughout American history, mostly disguised by the neatness and false civility of people like Sessions. Trump allowed it to be open, public, and shamefully obvious. The shift in the state, and what Tuberville adds to the mix, are the pieces of the Trump stew that are missing from Sessions’ clean-cut, lawyerly racism: “REAL LEADERSHIP.” Tuberville, like Trump, is not of the “establishment.” He’s a coach.

Football coaches have always been revered in the South, and especially in Alabama. These are fundamentally political positions. As Howell Raines, a writer for the New York Times, noted upon the retirement of Paul “Bear” Bryant—the legendary leader of the University of Alabama Crimson Tide—the coach is a figurehead just as much as any politician.

In fact, longtime Gov. George Wallace actually feared Bryant running against him. At the 1968 Democratic convention, Bryant received 1.5 votes to be the party’s nominee for president, seemingly from nowhere. And famously, in 1971, Bryant integrated the University of Alabama’s football team over the objections of Wallace. Yes, it took until 1971. Bryant had been pushing for it for years, roadblocked by the segregationist governor (or, at least that’s the convenient narrative for Bear). Wallace relented after Alabama got torn up by the Black running back Sam “The Bam” Cunningham from USC—3 touchdowns, 200-plus yards. An Alabama assistant coach compared Cunningham’s role in integration to that of Martin Luther King Jr.

Still, Tuberville is not Bear Bryant. But his use of name recognition, celebrity, and whatever policy is popular on conservative radio and TV (even if it happens to be the one Sessions invented) is very Trump.