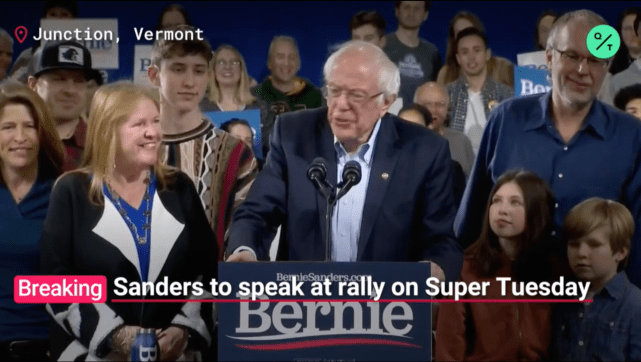

Bernie Sanders arrives for his primary night rally in Vermont.Matt Rourke/AP

Bernie Sanders, the Vermont democratic socialist, has been trying for five years to convince Democratic and independent voters to join a political revolution and back his hostile takeover of the Democratic Party. He has drawn thousands to his mega-rallies. He has inspired millions—many of them young and idealistic—and persuaded millions of American citizens to vote for him. But over the course of two presidential election cycles, he has so far demonstrated that most voters do not want the Sanders revolution.

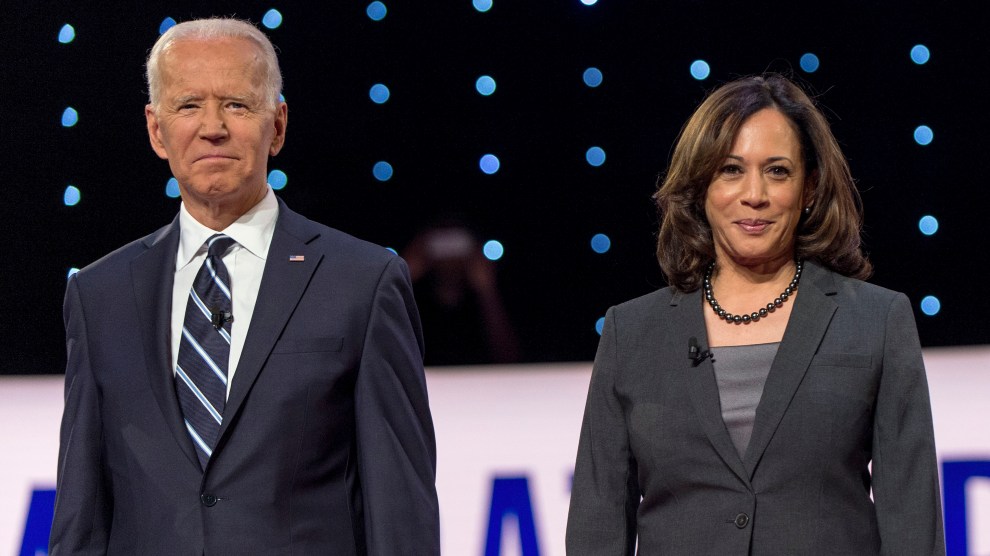

Joe Biden’s victories on Super Tuesday have been hailed as one of the most stunning and impressive comebacks in presidential politics. But this collection of primaries was also a referendum on Sanders and his effort to sell democratic socialism to America. The frontrunner heading into these crucial contests, Sanders was soundly beaten by a guy who, across three presidential bids, had never won a primary until three days earlier in South Carolina. Once other non-Sanders candidates had dropped out and backed Biden, the picture became clear: The Democrats are not the party of revolution—at least not yet.

That shouldn’t be a surprise. Though Sanders had won two of the first four contests (and was essentially tied for first in another) and pundits were huffing that he might be unstoppable, his showings did not indicate he had won over enough Democratic voters for an easy remake of the Democratic Party. In those races, he received 25 percent, 26 percent, and 34 percent of the initial vote, which was enough to place him at the top of a crowded field. Four years ago, though, he collected 45 percent of the primary vote total when he ran against Hillary Clinton. He has been far below that this time.

Sure, there were more contenders slicing up the pie. But his drop indicated that many of the 2016 voters who had supported him had moved on—a sign that they had been with him back then because he was the only alternative to Clinton, or that they now are looking for something else, or that they think Sanders is not the right candidate to beat Donald Trump, or a combination of all this. Sanders’ win last month in New Hampshire was telling. In 2016, he bagged 152,000 voters in the Granite State and achieved victory with 60 percent of the vote. This time, Sanders won again, but with 76,000 votes and a quarter of the electorate. His band of rebels eager to take on the Democratic establishment had fallen in half.

The results from the first four states combined with the early numbers out of Super Tuesday—they are still tallying in California—have Sanders at 28 percent of the combined vote. Biden pulled 35 percent. (Mike Bloomberg and Elizabeth Warren each gathered between 12 and 13 percent.) That Sanders figure, which may creep up, is not close to the 45 percent he earned against Clinton overall.

All this suggests that Sanders has not expanded upon his impressive 2016 run—and that his revolution is less popular now than it was four years ago. Many mainline Democrats have worried that should he gain the nomination, the general election would shift from a race about Trump to a contest about Sanders and socialism (and that this could have a disastrous impact on Democratic candidates running for the Senate and House). There’s no way to know if such a fear would come true before giving it a shot. But the Democratic Party, it turns out, has been hosting a form of this experiment, and Sanders has not fared as well as he had anticipated.

At the heart of Sanders’ presidential bid has been two core elements. First, he’s a different sort of candidate with a different sort of politics. He has campaigned as an authentic, no-bull, and dedicated ideologue who champions a clear critique of a corrupt political order dominated by billionaires and corporate interests, and as a visionary who offers a set of wide-ranging structural proposals to make the United States a more just and equitable society. Second, he and his team have claimed that because of all that, he creates a new political dynamic—one that will draw to the polls millions of citizens who have not previously voted. That is, his democratic socialism might scare off some voters, but the new voters he attracts—young voters, Latino voters, working-class voters—will dramatically reshape the electorate and provide the Democrats the winning margin.

The first part of his argument is undeniable. Sanders campaigns like no other national candidate. He doesn’t cut corners; he names names; he embraces a full-left agenda. And he has done so for decades. As such, he built a powerful grassroots movement that raised gobs of money for his insurgent campaign. He forged a relationship with supporters that few politicians do. He sparked an enthusiasm that other candidates can only dream of. But here’s the but: This has not caused millions of new voters to flood into the Democratic Party for a Sanders takeover. There has not been a historic surge of young Sanders voters—at least not enough to compensate for his poor showing among African Americans, suburbanites, and older voters. It’s true his voters tend to demonstrate more passion—and passion can help a party win a general election. But Sanders has yet to prove his theory of the case. That’s just math.

In the aftermath of Super Tuesday, some Sanders backers resumed the usual griping and moaning about the Democratic establishment’s opposition to their movement. Marianne Williamson, the New Age author whose presidential bid fizzled and who has since endorsed Sanders, described Biden’s win as a “coup,” as if these victories were the rigged product of a conspiracy mounted by Democratic powers-that-be. Such talk helps Trump more than anyone else.

Moderate Democrats worried about a Sanders nomination did indeed rally to Biden after the former veep showed he was capable of winning a primary in South Carolina. But that was no secret plot. It was a natural development. And the party establishment’s revulsion at the prospect of a Sanders’ triumph is hardly a shocker. Sanders has not been a member of the Democratic Party. (He still identifies as an independent in the Senate.) Moreover, his socialism could be a problem in the general election. (Throughout his long career, Sanders has never faced hundreds of millions of dollars in attack ads that attempt to brand him as a far-left wacko outside the American mainstream—which is likely to occur should he become the nominee.) There is no way the party was going to warmly welcome him into a loving embrace.

That’s the challenge for a maverick. Sanders was crashing the party. It’s not supposed to be easy. Yet the Democrats, in several ways, allowed him that opportunity. In 2016, some state party chairs considered trying to keep Sanders off the primary ballots in their states. The Democratic Party chair at the time, Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, told them not to do so. And those Democratic emails that the Russians stole and released through Wikileaks? They showed no true effort on the part of Democratic insiders to do in Sanders. There was some jiggling of the debate schedule, but it turned out not to cause Sanders any real trouble. And in 2016, as in 2020 (as of yet), Sanders did not have to contend with a massive blitz of negative ads from Democrats. (That could change in the coming days and weeks. There were some anti-Sanders ads run in the days before Super Tuesday by a group organized by centrist Democrats.)

Sanders has had a wide open shot at selling his brand of democratic socialism and at remaking the Democratic Party in his own image. All he had to do was get enough votes to overcome the built-in advantage for the moderate, non-socialist candidate favored by the party’s establishment. Ultimately, most Democratic primary voters have said no thanks.

Long before Super Tuesday, Sanders had succeeded in becoming a brand-name politician. People knew him and knew what he stood for. After years of decrying dirty-money politics, fighting for progressive causes, and preaching revolution, Sanders had achieved market saturation. The same perhaps could be said for Biden. Despite all his stumbling in the previous months, Biden was as well-known a quantity as a politician can be. It was a fair fight—even though Sanders had millions of dollars more and Biden was low in resources and had done poorly in Iowa and New Hampshire. The revolution fought the moderate, and the moderate won.

The Democratic race is not over. The past few days have made a watchword of “volatility.” Both Biden and Sanders have distinct liabilities. The see-saw ride may not be done. But this much has been determined: Sanders, the great progressive advocate, has tried to present his case as one of inevitability—only he and his version of democratic socialism could defeat Trump, and this could only be accomplished by rousing revolutionary fervor to radically remodel the Democratic electorate. At this stage of the crazy 2020 contest, the results are not with him.