"BEES?"Fox Broadcasting Company

Arrested Development is finally (for real this time) coming back. On May 26 at exactly 12:01 a.m. PDT, the series’ fourth season will debut exclusively on Netflix, the on-demand streaming service that on any given weeknight accounts for nearly a third of internet traffic in North America. It’s a hotly anticipated premiere that fans are praying will not crash the website.

This TV series—about a spoiled family wading through a glut of personal, financial, and international scandal—occupies a place in popular culture that few other shows have managed to reach. Fans have even witnessed Arrested Development burrow itself into Western politics. In March 2011, before NATO forces launched an air war that would help topple Moammar Qaddafi‘s mass-murdering regime in Libya, The New Republic ran a fantastic slideshow comparing the notorious Qaddafi family to Arrested Development‘s Bluth clan. During a speech this month in the House of Commons of Canada, opposition leader Thomas Mulcair quoted a famous episode of Arrested Development while criticizing the prime minister for over $3 billion in unaccounted anti-terrorism funding. And as the series revival neared, Republicans started dropping Arrested Development references to ridicule the Affordable Care Act, Democratic leadership, and the Obama administration.

The series has also found its way into the syllabi of college courses, and onto the pages of academic essays. “The writers worked miracles addressing philosophical and social issues,” says J. Jeremy Wisnewski, an associate professor of philosophy at Hartwick College who served as a volume editor on the book Arrested Development and Philosophy. “To see the way race, gender, sexual orientation, and class are handled in the show is to witness genius at work.”

There’s something else the show handled so well that’s often taken for granted: During its original run on Fox from 2003 to 2006, the series delivered what was arguably the sharpest satire of the Bush era and the Iraq War that has been broadcast on television.

Eight years of George W. Bush left us with plenty of televised satire, some of it good, and some not so good. The Daily Show and The Colbert Report held up a scathingly satirical mirror to the media and that presidency on almost a nightly basis. South Park was often sublime, and never partisan, when commenting on Bush-era woes. Chappelle’s Show had the phenomenal “Black Bush” sketch. (On a related note, Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter has written about how the Scott-Schrute dynamic on NBC’s The Office doubles as an allegory for Bush-Cheney.)

But Arrested Development, during its brief three-season run, stood shoulders above the rest as the least forced, most creative, and—even though it was shackled by FCC rules and regulations—most ingeniously obscene comic examination of Bush-administration dysfunction.

Let’s start with the obvious highlight: The show reduced the administration’s WMD intel make-believe to an unflattering and fitting metaphor it so richly deserved: “Balls.” That’s right—balls. Straight-up balls. Honest to goodness, balls.

In the second-season episode “Sad Sack,” prosecutor Wayne Jarvis believes that Bluth patriarch George Sr. aided Saddam Hussein by building homes over underground facilities containing weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. Jarvis, who is convinced that the Patriot Act grants him the right to do just about anything, invokes the 2001 law to seize Bluth family records, which include a photo believed to show conclusive evidence of WMD in Iraq. The photo reaches the highest levels of the federal government and military. Jets are scrambled. The Pentagon is whipped into a frenzy. The image is splattered all over the evening news by a gullible national press.

Turns out the photo didn’t show any weapons or Iraqi desert. It was nothing more than a close-up of a man’s testicles, specifically those of “never-nude” Tobias Fünke:

When handed the corrected intelligence reports, politicians and military leaders scream, “BALLS?!” as warplanes turn around and abruptly return to base.

The sad (and sort of brilliant) thing about this was that as crude and ridiculous as the big reveal was, it wasn’t that over-the-top; in the run-up to invasion and during Colin Powell’s infamous appearance before the United Nations, the Bush White House presented—and much of the press and public bought—evidence that was so shaky they might as well have been waving around a blurry photo of some balls.

At the show’s goofiest moments there was frequently a lingering mood of a nation gone to war. One of the central story arcs of Arrested Development concerns whether or not George Sr. committed “light treason” by doing business with Saddam Hussein in the years prior to the war in Iraq (an alleged crime the show at one point giddily compares, with dark irony, to the totally authentic photo of Donald Rumsfeld shaking hands with the dictator). And throughout the three seasons, there are numerous references to the bungled American war effort.

Take, for example, the season two episode “The One Where They Build a House,” when the thoroughly inept, wannabe playboy Bluth son Gob manages the construction of a Potemkin model home for a press event, even playing the jingle, “Solid as a Rock“—which Gob fails to realize sounds exactly like “Solid as Iraq.” Gob’s presentation of his worthless project features a large banner that might look familiar to you:

Also in season two, Arrested Development took on some human rights abuses that were committed in the name of the United States.

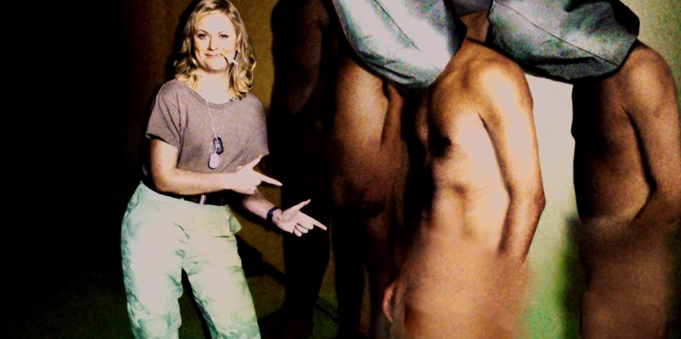

Here’s the show’s take on the Abu Ghraib scandal, featuring guest star Amy Poehler:

Despite the fact that the series’ focus wasn’t actually real-world politics, the original 53 episodes were littered with nods to the Bush years (hunting for Saddam, Iraqi military ineptitude, war protests, botched CIA operations, Buster Bluth in Army uniform, and so on). And though the writers’ room (led by creator Mitchell Hurwitz) almost certainly leaned to the left, the political satire was never weighed down by partisan indignation; it grew out of the times, not a determined ideologue’s mind. The satirical jabs—much like the series’ chronicling of the decadent and depraved Bluths—were motivated by gleeful scorn aimed carefully at power, scandal, and rank incompetence.

It all makes you wonder how the next 15 episodes will handle the age of Obama.