I ring the buzzer at a downtown San Francisco rehearsal space and the door swings open. Mike Burkett, sporting a fading pink mohawk, offers a handshake as he shows me up the stairs.

Burkett, 48, is best known as Fat Mike, founder of the San Francisco record label Fat Wreck Chords, and the irreverent frontman of legendary punk band NOFX. With its unique brand of raucous pop-punk and onstage antics, the band has sold millions of records, cultivating generations of fans in the three decades they’ve been performing.

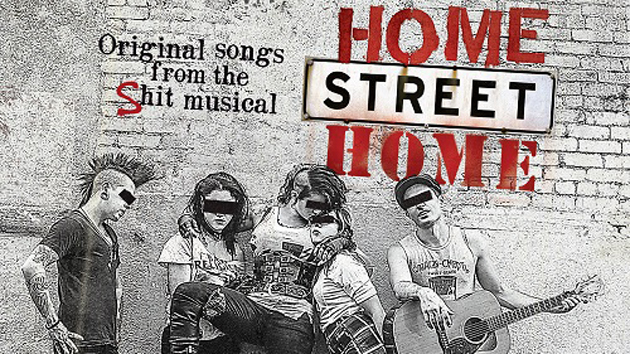

Now, after five years of writing, finessing, reworking, rehearsing, and self-medicating to complete Home Street Home, his new Broadway-style musical production, Fat Mike is hoping to win over a different audience, and bring them into his world, for a couple of hours at least.

Home Street Home tells the story of a young runaway who joins a “saucy tribe of slutty, castaway street punks,” according to the website description. Along with a catalog of infectiously catchy songs, it offers audiences a “celebratory exploration of sex work, drug use, pain, and BDSM power exchange.”

But don’t expect another cheesy rock opera or genre-bending attempt. In addition to writer/director Soma Snakeoil (a professional Dominant and fetish-movie star who is now Burkett’s fiancé), he’s brought in Jeff Marx, co-writer of the Tony Award-winning musical “Avenue Q,” and veteran Los Angeles stage director Richard Israel. On the day of my visit, with just two weeks left before opening night, the cast and crew were working out the final kinks and last minute changes. It was almost ready.

“We are just about to rehearse the roughest scene,” Burkett tells me over his shoulder as we walk into the bustling studio. We sit across from the performers, and he whispers explanations about what we’re seeing. The scene is a flashback that reveals why Sue, the lead character, ran away from home. When Burkett starts describing the accompanying song, I tell him I’ve already listened to the entire soundtrack. “What did you think?” he asks anxiously.

In truth, I hadn’t just listened to it, I’d devoured it. The soundtrack was released in advance of the show, and featured plenty of punk-world notables. A partial list includes Frank Turner, Alkaline Trio’s Matt Skiba, Tony Award winner Lena Hall (Hedwig and the Angry Inch), Dance Hall Crashers’ Karina Denike, and members of Descendents, Lagwagon, the Mad Caddies, and Me First and the Gimme Gimmes. Even the late, great, Tony Sly shows up on one of the tracks.

I already knew most of the words, had picked out my favorite songs, and had been unsuccessfully fighting to get them to stop looping in my head. Even with limited knowledge of the plot, the songs stood on their own, a strange but perfect marriage of the peppy show tunes I grew up on and the punk rock that helped me find myself as a teen.

NOFX, and many of these other bands, played a big part in that, so it was surprising to learn that Fat Mike cared about my opinion. Wasn’t he, after all, the fearless role model of the “don’t give a fuck” philosophy so many of us tried to embody as insecure teenagers?

“I liked it a lot,” I answer simply, before Burkett concedes his anxiety over how the soundtrack would be received. He’d written it, after all, more with Broadway in mind than 924 Gilman Street. Breaking into the theater world was a lifelong dream.

“The first record I ever heard was Rocky Horror Picture Show,” he recalls. “I saw it on TV—too young, like 8 or 9—and I taped it on my tape recorder. Held it up to the TV and taped it. And that is what I listened to for years. That is what I am trying to do. Just how Rocky Horror changed my life when I was a kid. Growing up, that phrase—’Don’t dream it, be it.’—that stuck with me forever.”

But there’s still work to be done and Burektt won’t be satisfied with good-enough. He jumps up frequently to weigh in on the details, from costume fittings to vocal range. “We have to train these people to sing punk,” he says with a smile. “No vibrato allowed!”

With Home Sweet Home, he’s had to pick his battles—frustratingly foreign territory for a guy used to calling the shots. “For a NOFX record, I write usually 15 songs, finish em, no one says shit to me, and I decide which 12 I like best. For this, I had 28, 29 songs, and one by one they just keep getting cut, cut, cut. I write the song and the director goes, ‘This doesn’t make any sense’ and ‘You can’t write this’ and, ‘This is not what we are trying to go with here.’ Songs I spent months working on!” he says. “So, people are telling me what to do, from fucking every direction!”

Even the way he writes songs needed to be adjusted. “All the songs I wrote for this originally were just songs, and I thought we could build a story around it. But the songs have to be story-driven. The goal in the musical is to have people talking and then suddenly they just go into song. It is not like, ‘Hey, here we go!’ and ‘Watch this one!’ and then you start singing a song about elephants or whatever. You have to write lyrics thinking about what’s happening.”

He and Soma often acted out the roles as they wrote to make sure the lyrics were realistic and that the song was building the story. It wasn’t that much of a stretch, considering that much of the storyline was culled from their own lives. Both spent time on the streets as teens, relishing in the freedom and seeking solace in the company of other street kids—many of whom are reflected in the play’s characters.

Some of them turn to prostitution to survive. Others to drugs and alcohol. And the story includes many situations that may be hard for some people to stomach. But Burkett sees it as an honest portrayal of teens living on the street. They don’t want your pity, he emphasizes. These kids are not lost souls.

“The show is about chosen family. How all these kids move to the street because it was better. How these kids were all screwed over but they are all happy and they are in a great family,” he says. “Looking down your nose at people is ridiculous. And that’s what this shows, that these kids are happier than most of the fucking people in the world—even if they are homeless and hookers and drug addicts.”

Burkett hopes his new audiences will be open to a culture and experience that might seem to them far removed. “You feel a little bit odd to the world. You feel different. And that’s why it all started right? People don’t fit in. That is what is punk about it,” he says. “These kids are outcasts and had really shitty childhoods and they came together.”

Home Street Home opens February 20 at Z Space in San Francisco. For now, there are only 11 performances scheduled. Burkett hopes it will go far beyond that. “I hope it is as successful as Avenue Q or Hedwig. My goal was to write something similar to Rocky Horror—a cult classic musical. And I think we have done that.”

If nothing else, Burkett offers audiences a new way to see stories from the streets. “None of this was about anything except writing something that is going to be really remembered,” he says. “I think people’s attitudes will change from this—maybe they will look at street people and drug users and prostitutes and get a good glimpse of people who chose their family.”