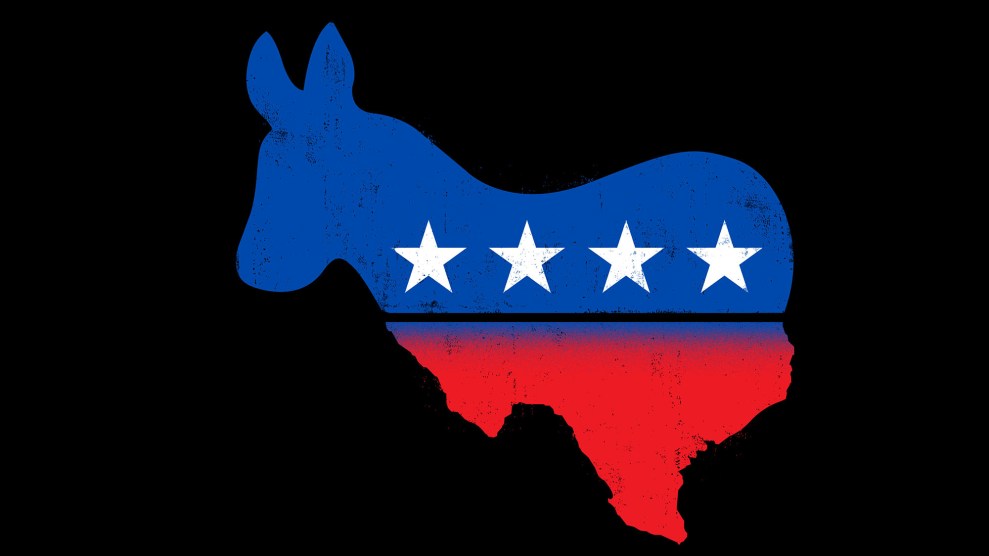

It was a vision of the Democratic Party’s enduring dream for Texas: a charismatic and telegenic candidate backed by a crowd of cheering, flag-waving Latinos and Latinas, the demographic long expected to end nearly three decades of Republican political dominance. Inside a wood-paneled party room of a bowling alley, in cowboy hats and blue jeans, they chanted “Beto! Beto!” as national news cameras framed their shot on a recognizable political star.

But a closer look at the scene in the border city of Laredo revealed signs of an emerging dream. Among the crowd at the rally for gubernatorial candidate Beto O’Rourke was Jessica Cisneros, the 28-year-old immigration attorney from Laredo who is challenging nine-term Rep. Henry Cuellar in a repeat of one of 2020’s most intense primaries. Nearby, anti-border-wall activist Tannya Benavides, another Cuellar challenger, waved a tiny flag. A T-shirt in the crowd hinted at the arrival of a new South Texas progressive vanguard: Females of the Future.

Cisneros and Benavides are among a group of Latina Democrats mounting denim-and-boots primary runs in consequential and competitive Texas races this cycle. To the east, in the Rio Grande Valley, Michelle Vallejo—the Ivy League–educated co-owner of Pulga Los Portales, an enormous flea market—is running to replace Rep. Vicente Gonzalez in the district he abandoned after redistricting changed its borders. And further east, in Brownsville, attorney Rochelle Garza, a former American Civil Liberties Union attorney best known for suing the Trump administration in an abortion rights case involving a young immigrant in detention, launched her campaign for state attorney general.

That they are all running unabashedly progressive campaigns from South Texas is significant. In 2020, Donald Trump made serious gains in majority-Latino counties located near or on the border, and since then, pundits and journalists have become obsessed with every twitch of the area’s Latina Republicans, who are pushing a combination of religious, anti-abortion, and tough-on-the-border messages. As one Politico piece put it, they’re targeting voters who “worry the left is forgetting family values and the value of work.”

The new crop of Latina Democrats, though, are telling a different kind of story, one they believe resonates in working-class South Texas. The progressive policies they’re championing, like a $15 minimum wage and Medicare for All, aren’t some form of government handout, but rather a means of dismantling pervasive inequities, particularly in a region where median incomes are roughly half the national mark and nearly 30 percent of residents are uninsured. All Americans should have a shot at success, they say—and shouldn’t be stymied by elites who’ve gamed the system.

They have set out to upend a centuries-old business and political status quo that marketed the region as a source of low-paid labor force—first in the cotton and oil fields, and later the service industry—and conceded its landscape to right-wing visions of a weaponized border. The border, they remind voters, is made of the bridges that connect family and neighbors, not the walls that separate them.

“For so long, it seems we’ve only been deserving of investments in the form of militarization on the border or investments in terms of extracting our natural resources,” Cisneros told me over coffee a day after the O’Rourke event in Laredo. A few months later, at a fundraiser in Mission, Vallejo told donors, “We are deserving of more.”

In Cisneros’ vision of South Texas, the region’s working class powers a thriving green economy. “There is going to be a transition into a renewable economy,” she said. “I want South Texas to be at the forefront of that. Because if we make the investment now, it will make us a leader in the entire nation.”

When she talks about the green economy she wants to see flourish, Cisneros starts with her experience growing up the daughter of a truck driver, not with greenhouse gases or melting glaciers. To her, green jobs are part of a reimagined South Texas that honors its working class. She knows that while drilling jobs pay families into the middle class, the industry is also prone to frequent layoffs, and oil patches can be an eight-hour drive from home, meaning paying for housing and meals in two places.

It also means splitting up families for weeks at a time. “I know how difficult it is not to have your family member at home for two weeks, because that’s what my dad had to do,” Cisneros told me. To promote her vision of a green economy for South Texas, Cisneros said she asks voters: “How great would it be if those well-paid jobs would be available here?”

It’s a message that helped get Cisneros, who is once again backed by Justice Democrats, within percentage points of defeating Cuellar last cycle—and a similar platform to the one that helped Bernie Sanders carry all but a few border counties in the Democratic presidential primary. It’s also meant to counter Republican messaging about the oil and gas economy that helped Trump capture votes in the region.

Few issues were as ripe for alarmist messaging than the state of the oil and gas industry. In the year leading up to the election, 60,000 to 70,000 workers were laid off. “Trumpers were knocking on doors, telling people their oil and gas jobs were in jeopardy,” said Sylvia Bruni, the chair of the Webb County Democratic Party, which is based in Laredo. “‘If you don’t vote for him, you’re going to be homeless.’” Similar reports were heard across South Texas, with one Democratic leader in neighboring Zapata County, which Trump carried in 2020, telling me his sister began organizing other women to vote for Trump. A weathered billboard near the Laredo city limits still reads: “Save your Oil and Gas Job. Vote Republican.”

For Bruni, the party’s slippage in 2020 wasn’t all that surprising. “We telephone-banked with a flattest message ever—there was no message,” she told me. “We didn’t tell our story.” Meanwhile, South Texas Latinos were facing financial ruin due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Unemployment soared, and in a region of blue-collar workers, staying home was not an option for many.

When Gov. Greg Abbott quickly lifted the shelter-in-place order, the decimation that followed was nearly incomprehensible. A high school classmate of mine lost her mother and two sisters. Conflicting information spread as the state pushed people to return to work. Another friend sobbed in frustration because her cousin, who went back to work as a truck driver, lived with a vulnerable relative.

Instead of addressing this moment of pain and loss ahead of the election, Democrats responded with recycled promises of immigration reform. It was as if Latinos were another brightly colored egg in a box of cascarones, the confetti-filled eggs popular during Easter here—one with an identity distinct (immigration) and separate from the American core. According to an in-depth report by the research and communications firm EquisLabs that focused on Latino voters in South Texas and Florida, many South Texans cited reopening the economy to earn a living as a top reason for supporting Trump.

The Republican message, meanwhile, amounted to a modern “red panic,” according to an EquisLab report that described South Texas as a site of “uncontested propaganda in isolated media ecosystems…It’s a story about the weaponization of the American Dream—the true opposite of socialism in the right-wing narrative.”

In the garden of a donor’s home in the Rio Grande Valley in late January, Vallejo rejected the impulse of other Democrats to stake a position relative to the Republican definition of American identity and values. “I’m definitely proud to be pro-choice,” she told her audience. “Access to abortion is health care, period.”

Vallejo is a late entry to a crowded primary in the 15th Congressional District, which meanders from McAllen to San Antonio, more than 200 miles away. The daughter of Mexican immigrants, she entered the race through a public nomination process sponsored by Lupe Votes, an arm of the worker rights group La Union del Pueblo Entero, which traces its roots to the 1960s farmworker movement. She was selected out of the 30 nominees for her progressive positions and her experience running a business and launching a networking group for women entrepreneurs.

Before she decided to run for office, Vallejo said, choice had always been seen as a religious issue in her family and best ignored if opinions didn’t align. Once she got in the race, it forced a conversation about her beliefs with her grandparents—a conversation that ended up challenging assumptions they had about each other and bringing them closer together.

Afterward, 23-year-old Leslie Tovar, the niece of one of the guests, said that to hear a woman and candidate assert a pro-choice stance represented a rebuke to shame and guilt that permeates the issue in the Rio Grande Valley. Silence had allowed misinformation to spread, she said, like a belief that access to abortion made the procedure an inevitability.

While Cuellar was the sole Democrat who voted against the Women’s Health Protection Act, meant to codify the Roe v. Wade decision, more than 60 percent of Latinas in Texas told pollsters that abortion was a private matter between a woman and her family and doctor. Last year, Edinburg, which is located in the 15th District, was among a handful of Texas cities where public outcry forced the city council to reject an ordinance that would have outlawed abortion and declared the city “a sanctuary for the unborn.” The city received dozens of emailed comments, with one describing the ordinance as “barbaric,” another attacking the all-male council for regulating human bodies, and yet another incredulous that the voice of Mayor Richard Molina, under indictment for voter fraud, “still matters yet women’s voices don’t.”

Defending abortion access was also how Rochelle Garza, the state attorney general candidate, made a name for herself. Back in 2017, while in private practice, Garza sued the Trump administration on behalf of a 17-year-old immigrant known as Jane Doe, who was seeking an abortion while in ICE detention. Garza won in district court, and the case eventually ended up in front of the DC Circuit Court of Appeals—where then–Justice Brett Kavanaugh argued against granting “a new right” to “unlawful” immigrant minors.

Garza eventually prevailed in the DC Circuit, and her client underwent the procedure. In her testimony during the Senate hearing for Kavanaugh’s nomination to the US Supreme Court, Garza described the borderlands as “a place where absolutely everything converges, and everything coexists.”

Standing in front of her ancestral home in Brownsville, Garza said that convergence extends to the defense of rights that extends from Jane Doe to all Texans. “The erosion of rights begins with the most marginalized,” she told me. “When we make too many exceptions to the rule, the rule no longer exists. That’s what’s at risk when it comes to our individual freedoms.”

In 2017, Texas passed a law that empowered law enforcement, including campus police, to question people about their immigration status. Three years later, Texas passed an abortion law that empowered private citizens to collect a “bounty” on anyone who seeks an abortion after six weeks, or on anyone who facilitates the abortion. In February, Greg Abbott directed a state agency to investigate gender care for trans kids as child abuse.

These laws, Garza said, reflect a decision by elected officials that some people deserve fewer constitutional protections. Depriving some, she says, risks all.

On a drive from Laredo to the Rio Grande Valley, I pulled off the highway for a telephone interview with Zaena Zamora, the executive director of the Frontera Fund, which provides financial assistance to people seeking abortion services in South Texas. Fifteen minutes into our conversation, a state trooper stopped and asked if I was okay. Then another passed by, then another, and another. Others had two motorists pulled over within eyeshot.

An indignant Zamora said the police presence was an example of how issues of abortion, border security, immigration, and economy—most of their clients are working mothers—all intersect. The state’s new abortion law, she said, was “another way to police us. It’s a way to control people’s bodies.” In South Texas, she said, border checkpoints are located 80 miles inland, and people grow up thinking that the countless drones, Black Hawk helicopters, surveillance towers, military convoys, and state troopers are normal. Much of the voting-age population has little to no memory of the region before the border security build-up that started with the Clinton administration and later accelerated after September 11.

Latina progressives trying to reclaim the border security narrative must wrest a gun from Republicans that had been loaded by Democrats like Cuellar, who has boasted of bringing in nearly $45 million in border security funding to Webb County and who voted with Trump more than any other congressional Democrat. South Texans who heard then-candidate Biden promise “not one more foot” of Border Wall construction later read about the acres of family-owned land condemned by his administration for border wall construction. They have seen Democrats who once decried the border wall as “racist” fail to use their majority to rescind funding for a border wall that the government plans to extend the length of the Rio Grande Valley.

After the Trump administration abruptly halted border wall construction last year, critically needed levees were left in disrepair. In the Rio Grande Valley, elected Democrats joined state Republicans in pressuring the Biden administration to build the wall as a means of repairing the levees.

At times, South Texas Democrats simply adopt Republican positions whole cloth. Weeks after his home and office were raided by FBI agents, Cuellar attacked a Cisneros rally featuring Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, saying, “The voters will decide this election, not far-left celebrities who stand for defunding the police, open borders, eliminating oil and gas jobs, and raising taxes on hard-working Texans. Members should take care of their own district before taking failed ideas to South Texas.” With Democrats using that kind of GOP rhetoric, how are voters supposed to know the difference?

In 2020, the absence of a counter-narrative on the border from Democrats translated into gains for Trump. “Republicans owned the border issue without any meaningful competition,” wrote Equis Research. Since then, national Democrats have idly stood by, avoiding the border as Republicans have ferried governors and attorneys general across the region for photo-ops.

Vallejo has attacked the border wall as a failure because it has sowed division and resulted in the government seizing family-owned land. Garza has called the governor’s deployments of armed Texas National Guardsmen to the border “unconstitutional.”

In Vallejo’s district, Monica De La Cruz Hernandez, the Republican who narrowly lost to Gonzalez last election, has made border security her singular issue, complete with a campaign ad that features a helicopter ride across a landscaped stripped of foliage. Viewers don’t see the hundreds of birds and butterflies that migrate through the region annually, attracting international visitors, or the families fishing on the Rio Grande. They see a political symbol.

That symbol, of course, has its own kind of power. On a Saturday afternoon in late January, a small crowd descended on a section of the border wall outside McAllen as part of a three-day We Stand United gathering that featured Michael Flynn, Trump’s former national security adviser. After linking arms and praying for law enforcement, they mingled on the levee, some with pistols holstered at their hips and Mexican beers in their hands. They posed for photos where the section of the border wall built by the Trump administration connects with the wall built during the Obama administration. The two sections are separated by a gap, a window that gives way to a sweeping view of rustling grasses and distant brush.

A few miles away, Vallejo told potential donors that a critical problem facing the residents of Granjeno, where the beer-drink-pistol-packing crowd of outsiders had gathered, was lack of internet access.

When it came time for the Q&A, a woman in the audience asked about a different kind of challenge: “You are up against the [local political] machine—that doesn’t make you flinch?”

“People like us are capable of representing us,” Vallejo said, near a table with cookies decorated with the slogan: We the Pueblo.

For decades, it was a radical notion that the pueblo could represent itself. For the first half of the 20th century, politics in South Texas was dominated by white-only primaries, a poll tax, and, at times, violent suppression by law enforcement. Parties carried less significance. “Politics was decided by a white minority, the few wealthy Mexican American families, and backed by their lieutenants,” UC Berkeley historian and sociologist David Montejano told me via email. “The Mexican-American vote was controlled.”

Democrats came to dominate South Texas for decades, and despite recent challenges, vestiges of the machine remain. “We’re known for the patrón system,” said Tannya Benavides, who is running in the primary against Cisneros and Cuellar. “And that’s exactly what we’re trying to defeat.”

Discontent with the machine was partly how Republicans first made inroads in the region. In 2010, a state legislator from Edinburg, Aaron Peña, defected from the Democratic Party to become the GOP’s first Latino state representative. Peña had complained vocally that Democrats took Latinos for granted.

Three years later, I interviewed Peña about border security after a high-profile incident in which he said immigration officials had unfairly harassed him and impounded his car. Peña had voted for a bill to divert additional funding to border security, and though he supported it as an anti-drug trafficking effort and as economic investment, he told me it was also a way to placate growing nativist sentiment. Nearly a decade later, state border security funding is in the billions and Peña’s daughter, Adrienne, the chairwoman of the Hidalgo County Republican Party, promotes a border security platform.

Latinas have become well-positioned ambassadors of Republican ideology. Mayra Flores, an immigrant from Mexico who is married to a Border Patrol agent and who is running in what’s considered a relatively safe Democratic congressional district that includes Brownsville, delivers a disciplined if policy-free message on social media that hits all the same notes: God, walls, and America.

To high school graduates Abril Orozco and Jocelynn Arellano, these Republican talking points reflects a status quo that pushes young people like them to leave home and look for opportunities elsewhere. At the bowling alley in Laredo, they said the state’s recent six-week abortion ban stripped them of their rights and choices over their bodies.

I asked them if Laredo was like my South Texas hometown, where, after graduation, the boys went to the military or the oil fields or became truck drivers and the girls became hair stylists, worked at Walmart or, if they were lucky, became teachers. It sounded like Laredo, they said. Then I asked if the lack of opportunities, and the feeling that they had to move away to succeed, was another way to control their bodies. Their eyes grew big, and then they told me theirs was an economic and political world built for men. “We women have to follow everything they do,” Arellano said. “They don’t make opportunities for women.”

Four months after she cheered in the background of O’Rourke’s rally, Cisneros joined Ocasio-Cortez and Greg Casar, an Austin city councilman also running for Congress, on center stage at an open-air music venue in San Antonio. Early voting in the primary was two days away. Speeches shifted seamlessly between English and Spanish. Liberal buzzwords were conspicuously absent from the speeches.

Cisneros told stories about the pact her father made with her and her sister—the parents would provide and the children would study—to explain the roots of her sense of collective effort. She described Laredo as a site of three immigrant detention centers, where “they imprison people like you and me and my family.”

Her proudest accomplishment, Cisneros told the crowd, was that their support had already reshaped perception of the border from a place of “crisis” to a site of political change.

Outside, a woman named Denise watched a group of MAGA protesters who had come to wave their flags and shout their vitriol. She said the protesters were trying to make them feel less American. But, she added, what she liked about Cisneros and the other speakers was that they made her feel anyone can be American, regardless of what you look like: “They bring out the best in people.”

But the challenges were clear for these progressive South Texas Latinas. The following week, Vallejo took the stage at an outdoor rally organized by the Tejano Democrats in the Rio Grande Valley, speaking shortly before O’Rourke took the mic. The group had endorsed Vallejo, and organizers had made it clear that candidates were not to use stage time for endorsements. But that didn’t stop Vicente Gonzalez—whose former seat Vallejo is seeking —from announcing, immediately before exiting the stage, that he was backing one of her primary opponents.

As soon as he stepped off the stage, Juanita Valdez Cox, executive director of Lupe, the group that selected Vallejo from the nominees, rushed Gonzalez, thrust a campaign placard at him, and said, “We picked her.”