On the warm May evening when the state of Tennessee executed Don Johnson for having murdered his wife, Connie, in 1984, there were two demonstrations taking place outside Riverbend Maximum Security Institution. Prison officials fenced off the area around the perimeter, and in a surreal moment that is part of death penalty vigils whenever an execution takes place in Tennessee, a correctional officer, dressed head to toe in tactical gear, asked, as if he were separating the guests at a wedding, if we were for or against the death penalty. He then directed us to the appropriate part of the field.

Technically, I’m neither. I am a reporter who, for the last few years, has been covering the death penalty for Mother Jones. I’ve spoken to activists and experts. Once, I interviewed an Alabama death row inmate a few days before he was executed for a murder he insisted he didn’t commit. After he was put to death, a friend texted me: “Wow, your guy is gone,” suggesting a personal connection to him that I confess our conversation had created. I remember his thick Southern accent, the intensity with which he was making his case as if I could make a difference, and the haunting realization that this man who seemed so fiercely alive would soon be dead not from natural causes but from a state that administered a powerful drug combination that his lawyers insisted would cause undue suffering.

There have been many nights I’ve stayed up late to find out whether the Supreme Court would spare a man’s life. Readers have sent me emails accusing me of “loving black murderers,” implying something insidious about my own blackness. (I thank them for reading Mother Jones.) I’ve written about the herculean efforts that states will make just to obtain lethal injection drugs at a time when European drug manufacturers refuse to continue their involvement in state killing. I have become both intellectually engaged in the questions surrounding the death penalty and personally unsettled by the continued insistence in more than half the states in our nation that this is a reasonable punishment, even as nearly every other country we consider peers have eliminated it. And many of those countries whose values we consider inimical to ours—North Korea, Iran, Iraq—continue it. But I have never visited a community where an execution was about to take place and never stood outside a prison with a crowd of crying, praying people at the moment the state kills someone several hundred yards away.

Listen to reporter Nathalie Baptiste talk about the death penalty in Tennessee with host Jamilah King on the Mother Jones Podcast.

After an identification check and a quick pat down, I walked up to about 50 people in the middle of a solemn prayer vigil. Johnson spent half of his 68 years on death row and during that time experienced a religious turning point that finally led to his ordination as an elder in the Seventh-day Adventist Church. As his execution date drew near, he refused any further appeals. His sole final and failed effort was a request to Republican Gov. Bill Lee for clemency. On the pro–death penalty side of the field was one man. Dressed in a long dark coat and a cowboy hat, he alternated between pacing and playing on his phone like someone in a crowded bar trying desperately not to look lonely. By the time I had arrived, Johnson had about half an hour left to live.

I decided to visit Nashville the day before Johnson’s execution because if there is such a thing as a “perfect” state to visit to understand the durability of capital punishment in America, Tennessee fits the bill. It has increased its rate of executions—after a nine-year hiatus—while other states, like Washington and New Hampshire, are abolishing the death penalty. Between 1960 and 2000, Tennessee didn’t execute anyone, but when “tough-on-crime” policies intensified and red-state lawmakers felt pressured to do something, Tennessee revved up its death chamber in 2000 and killed Robert Coe for the 1979 rape and murder of 8-year-old Cary Ann Medlin. Another six years would pass before the state put Sedley Alley to death, despite the pressing questions surrounding his possible innocence. Between 2007 and 2009, four more men were executed. Johnson’s execution will likely be followed by two more this year.

There are other ways Tennessee is representative of some broader themes that politicians, society, and the courts have grappled with surrounding this issue. As pharmaceutical companies worldwide decline to sell their drugs to US prisons, dozens of inmates, represented by Nashville’s Supervisory Assistant Federal Public Defender Kelley Henry (who also represented Johnson), filed a lawsuit against the state to halt its plans to use a controversial sedative responsible for several botched executions. (They lost.) And as DNA evidence has resulted in scores of exonerations of people who had spent years on death rows across the country as the result of wrongful convictions, the family of Sedley Alley is trying to get DNA testing done that could prove that Tennessee killed an innocent man. Then there is the fact that people of color are disproportionately represented on death row. Tennessee is no exception. Of the 55 men and one woman who are on death row there, 50 percent are black; Tennessee’s black population stands at 17 percent. But in contrast to so many death penalty stories, Don Johnson is white and healthy. He has admitted he was guilty of a terrible crime. This might have all the hallmarks of an uncomplicated execution.

My first stop was far from the bars that draw aspiring country music singers and the neighborhoods where future brides ride roofless buses with dozens of their closest friends. I drove to the far east part of town to the offices of Tennesseans for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, a nonprofit dedicated to ending capital punishment. With more than 10,000 supporters, the group mainly works out of Nashville but has chapters throughout the state. It’s similar to the other anti–death penalty organizations that have formed throughout the country.

I wanted to know what the hours before an execution were really like for activists so staunchly opposed to the death penalty, so I met with Stacy Rector, who has been executive director of TADP for the last 13 years. She’s an ordained Presbyterian minister with experience in ministering to death row inmates.

Rector is tall and speaks with a comforting Southern drawl. The statement “Honoring Life by Abolishing the Death Penalty” is emblazoned on a poster. TADP joins other organizations to educate the public about the death penalty and work to end it. Rector also served as a spiritual adviser to Steve Henley, who was convicted of the 1985 murders of Fred and Edna Stafford but insisted he was innocent and that his accomplice, Terry Flatt, had killed the couple. In exchange for his testimony against Henley, Flatt was given a 25-year sentence and paroled after five years. Rector and Henley both grew up on farms in rural Tennessee, so he “was very similar to many of the people I grew up with,” she said. “It just became a friendship.”

The last time Rector saw Henley was in the execution chamber. She led his family members in prayer as they wept. “I’d like to say that I hope this gives Fred and Edna’s family some peace. My experience in life is it won’t,” Henley said to his family before he died. “All my love to my mother and father, my sister and children. I’m an innocent man.” Henley’s story is replicated nearly everywhere that the death penalty is still practiced, Rector said.

“The system is broken,” she told me. “It is not fairly applied. It continues to risk executing innocent people.”

Johnson didn’t want to mount any last minute legal challenges. His clemency petition relied heavily on how he was transformed in prison from a violent murderer to a gentle person of faith. What that meant on a practical level was that there were no desperate last-minute appeal efforts, but there were more conversations about religion and forgiveness. “This is what Don wanted to do,” Rector said about his final request to the governor. He wanted the opportunity to be in front of the governor, fall “upon his knees,” and ask for forgiveness.

Mark Humphrey/AP

When a jury sentences a defendant to death, it begins a process that can take decades, cost millions of dollars, and require a small army of lawyers, many of whom end up growing close to their clients in the process of trying to keep them alive. Johnson was scheduled to be executed in 2006 and 2015, but both executions were stayed because of legal questions surrounding the methods the state uses to kill inmates. Kelley Henry has represented a number of death row inmates, including Don Johnson. I visited her at a large office building just across the street from the federal courthouse. Nestled in her cozy office, decorated with pictures of her family and comfortable chairs for lounging, Henry reflected on having gotten to know Don Johnson since she first became involved in his case in 2006. “I’ve come to care for him quite a bit,” she said. She’s come to think of Johnson and his supporters as her friends. “It has been humbling to get to know them and to see their goodness.”

“Goodness” is not a word that would immediately come to mind when looking at Johnson’s record. Like most people who end up on death row, he was raised in a chaotic household. His mother, Ruby, was only a teenager when she met James Lee Johnson, who was, according to the clemency petition, a “grown man.” They began a relationship but James Lee quickly became abusive. Ruby briefly ran away, had an affair, and got pregnant with Don. Worried about finances, she returned to James Lee. Don, who was born in January 1951, was raised to believe that James Lee was his biological father.

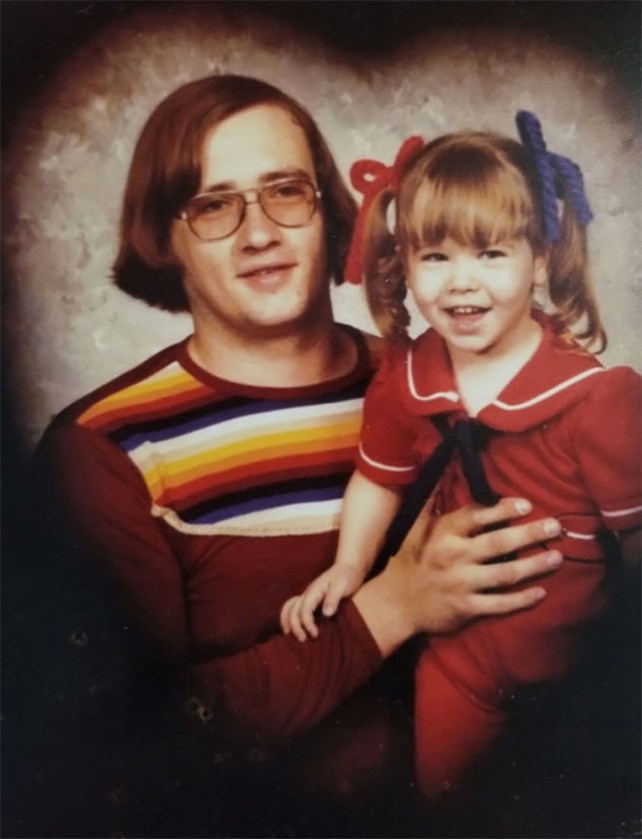

Then the cycle of abuse extended to the next generation. James Lee beat Don and Ruby, and Ruby, in turn, beat Don. As a teenager, Don spent time in a juvenile facility and an adult prison where physical violence was routine. According to his clemency petition, by the time Don left home for good at 18, he had learned little in school and was belligerent and violent; he believed women were meant to be abused. The petition contains scant detail about his life leading up to the crime that would land him on death row, but he describes himself as a liar, thief, and con man. In 1977, he married Connie, who had a young daughter named Cynthia. Together, they also had a son they named Jason. According to court documents, Don and Connie’s marriage was floundering, and Connie threatened to leave him.

A few weeks before Christmas in 1984, Johnson suffocated Connie to death, shoving a plastic bag down her throat. His accomplice, Ronnie McKoy, helped him put her body in the family van and move her to a shopping center. The next day, Johnson filed a missing person’s report and asked his boss to look for Connie’s van. Johnson’s boss discovered her body. Three days after the murder, Johnson was questioned by police and arrested. At his October 1985 trial in Shelby County, he was sentenced to die by the electric chair. Reading the reports of this brutal murder makes it easier to understand why, to death penalty proponents, Johnson is a monster.

But “goodness” somehow appeared during his three decades behind bars. In February 1985 while being held in the Shelby County jail, he heard an inmate preach, and converted to Christianity. While on death row, he joined the Seventh-day Adventists after two inmates introduced him to it, and in 2008 he became an ordained elder at Riverside Chapel, which routinely sent its members to build relationships with incarcerated people.

“I am heartbroken,” Henry says. “I think it’s going to be very hard tomorrow night to witness his execution,” That’s not only because she cares for Johnson, but because she has seen the effects of the drugs before.

For decades, most states used the three-drug combination containing sodium thiopental to render the inmate unconscious, pancuronium bromide to paralyze the inmate, and potassium chloride to stop the heart. Presumed to be a painless and more humane alternative to the electric chair, there is no scientific evidence proving that lethal injection is either. When the shortages of sodium thiopental began, states turned to Midazolam, a drug that would prove to be dangerous for executions because the sedative is not strong enough to render the inmate unconscious before the next dose of drugs. By 2009, death penalty states were struggling to find drugs, since European drug manufacturers refused to sell their product to American prisons. In one case, a state received a “donation” from a drug supplier after the Arkansas Department of Corrections director drove to meet an anonymous supplier in an undisclosed location.

Tennessee was not exempt from the problems of procuring the drugs, so the state attempted a workaround. In 2014, five years after the state’s last execution, former Gov. Bill Haslam signed a law that, in the event that legal drugs were unavailable, permitted the use of the electric chair—a method widely employed in the 1980s and 1990s but that’s considered inhumane today. Three years later, Henry represented 32 death row inmates in a lawsuit against the state over its three-drug protocol, alleging that their executions would amount to torture.

Henry has witnessed the executions of several clients and paints a gruesome picture of prisoners’ experiences. “When you hear people talking about coughing and gasping and snoring…that’s pulmonary edema beginning,” Henry says about the condition that feels like drowning. “And when you see them straining against the strap, grimacing, clenching their fists? That’s them starting to have that suffocation feeling from the paralytic.”

But still Tennessee pressed on and won its Midazolam case against the inmates. Executions resumed on August 9, 2018, nine years after the last one. Billy Ray Irick was put to death for the 1985 murder of 7-year-old Paula Dyer. According to media witnesses, during his execution Irick “jolted” and made a coughing or choking sound and briefly strained his arms against the restraints. He was pronounced dead at 7:48 p.m. His execution meant that after nearly a decade, the legal battles that were keeping Henry’s clients alive were no longer mostly symbolic. Her defense of her clients was literally a matter of life or death in Tennessee.

Connie Johnson was not the only victim of Johnson’s crime. The couple had two children, Cynthia (whom Johnson adopted when he married Connie) and Jason, the couple’s biological child. At the time of the murders, the children were 7 and 4 years old, respectively. In the days leading up to an execution, family members of the victims will often ask why so much attention is being paid to the person who committed the crime, rather than the people who are suffering. It’s also common rhetoric from death penalty supporters.

Unlike abolitionist groups, there is no organized pro–death penalty movement, but Kent Scheidegger has made a name for himself by explicitly supporting capital punishment and pushing for more executions. As legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, a right-wing think tank that opposes reforming the criminal justice system, Scheidegger has written more than 200 amicus briefs supporting the harsh punishments and the death penalty. He believes that the documented racial disparities on death row are “smoke and mirrors” and that the appeals process shouldn’t be dragged on for too long because “nearly all death-row inmates are clearly guilty.”

A large part of Don Johnson’s clemency petition to the governor was based on his adopted daughter’s forgiveness, but it was not always that way. When Johnson was first scheduled for execution in 2006, Vaughn was pleased. “I want the freak to burn,” she said in the clemency petition. The execution was called off because of the legal implications around using the electric chair. Six years later, when she was 35 years old, Vaughn decided to visit him in prison and confront him. As they sat together, she described what he had robbed her of, what it was like to go through life’s milestones—her high school graduation, her wedding, the birth of her child—without her mother by her side. Johnson cried while he listened.

And then that was it. Vaughn heard a voice telling her to let it go. “I forgive you,” she said to the man who killed her mother, and she meant it. In contrast, Jason Johnson, Vaughn’s brother, believes, like many victims, that this execution will bring closure, that it will somehow offer some solace for all the pain that was inflicted. “He’s an evil human being,” he told the Memphis Commercial Appeal a week before the execution. “That is all my father is. That’s all he’s ever been, is a con man.”

Retribution for a heinous crime, and the opportunity to offer the victims some consolation, has been a time-tested justification for the death penalty, as District Attorney Jody Pickens said when Urshawn Miller was sentenced to death in Jackson last year: “Justice was served and the citizens of Jackson will be protected from someone whose criminal history shows he is a very violent person.” But increasingly, victims of crimes are pushing back and asking that the death penalty not be an option. One such person is Charles Strobel, a Catholic priest who runs Room in the Inn, an organization that provides services for homeless people in Nashville. Dressed in a T-shirt and jeans, Strobel sits across from me at the large Room in the Inn complex. The 76-year-old Germantown, Tennessee, native speaks slowly and softly and apologizes for the tremor in his hands. He has Parkinson’s disease.

In the winter of 1985, Strobel was at his parish in Nashville when he noticed a group of homeless people in the parking lot, looking for somewhere to stay warm. He decided to open the doors and let them in. A year later, several congregations had decided to provide shelter and food to homeless people, and it grew to a large organization with 7,000 volunteers that house 1,500 homeless men during the winter. The following year, just as Room in the Inn was starting to grow, his mother Mary Catherine Strobel was abducted and murdered by a man who had escaped a facility for people with mental illness.

When I asked him about his mother’s death and his family’s push to spare the life of her killer, his voice remained steady. He described the night of December 9, 1986, when Mary Catherine disappeared after finishing some shopping. The 76-year-old, who was active in the Catholic church, was well known in the community as someone who was always giving food, clothes, and supplies to those in need.

William Scott Day, an inmate who had escaped from a facility for people with mental illness, grabbed her in the Sears parking lot, stabbed her, put her in the trunk of her car, and left the body at a bus depot outside of Nashville. Her body was found a day later. After Day was apprehended and convicted, Tennessee wanted to pursue the death penalty. “I already had a response in my head about what we needed to do going forward,” Strobel said, and organized his family to lobby against it. “We believe in the miracle of forgiveness. That’s what we said at the beginning of the grieving process and all the attention that came to us.” When I asked Strobel if people thought the family was “out of their minds” for opposing the death penalty, he chuckled. “That’s probably a good way of putting it.” He then opened up a folder and pulled out a document from 1986 and read me the statement he made on behalf of his family when Tennessee wanted to pursue the maximum punishment for Mary’s killer. In it he reiterates his belief in mercy and forgiveness, concluding, “I can think of no way that his execution would bring us satisfaction.”

Since then, he has met with families who can’t overcome the relentless anguish that comes with being the family member of a victim. “They were so close to the raw pain and the grief,” he says. “I didn’t feel that way. As hard as it is to forgive the person, it allowed us to move on and make some sense out of the rest of our lives.” Day died in prison.

Hearing stories like Strobel’s always brings me back to a central question: Would I have the capacity to forgive such a crime? The Strobel family not only asked Tennessee to spare his life, but also believed he was a “child of God, created in the image of God, and loved by God.” Too many of us struggle to forgive people who lie or cheat or steal. But Strobel is so steadfast in what he believes that forgiving the man who murdered his mother almost came as second nature.

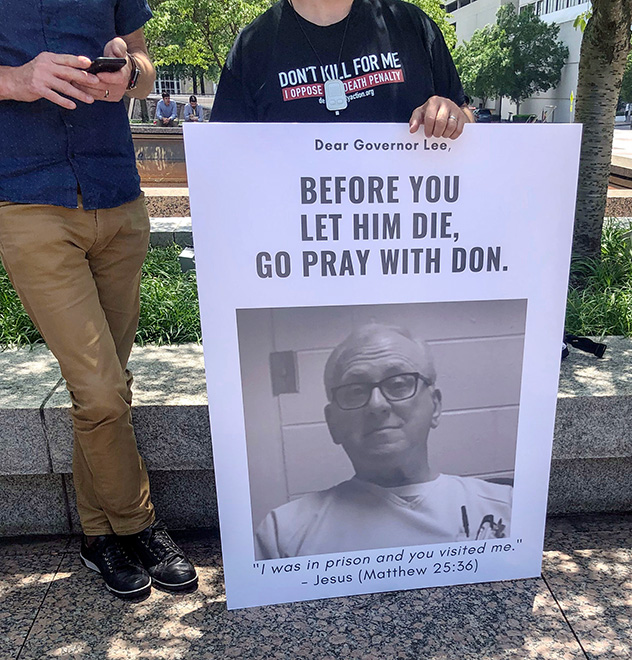

Don Johnson only had a few requests at the end of his life. In lieu of a last meal, he wanted the money to be given to a homeless person. He also asked the governor to pray with him and his fellow inmates before his death. I left Room in the Inn and headed to the Legislative Plaza at the state capitol to meet with Christian faith leaders Jeannie Alexander and Shane Claiborne, who gathered with a small group outside the governor’s office. They wanted to persuade Republican Gov. Bill Lee to talk to Johnson before he died, and had already made a failed attempt to enter his office the day before. They’re all a part of a loose network of faith leaders who actively oppose the death penalty. Alexander and Claiborne both have developed personal relationships with Johnson and would regularly visit him on death row.

While someone stood outside holding a big poster with a picture of Johnson’s face on it, the rest of the group went through security and gathered outside the office where they figured the governor was. Before I arrived in Nashville, Gov. Lee said the execution would go forward, but they hadn’t given up. Even if they couldn’t get Lee to change his mind, maybe they could at least persuade him to give Johnson and the other death row inmates a call. After a few minutes that felt maddeningly long, someone from the governor’s office came out to say the governor wouldn’t talk to the activists or pray with Johnson and the other death row inmates. Claiborne’s voice begins to crack. “We can do better for the victims than creating new victims,” he said. The group thanked the spokesperson for his time, and as he started to walk away, Claiborne shouted, “It’s not too late!”

Their last hope had been extinguished. Don Johnson was going to die in four hours. We wandered down to the Nashville Public Library and sat in the civil rights room, surrounded by posters of Martin Luther King Jr. and the great Georgia civil rights leader Rep. John L. Lewis. Claiborne and Alexander begin to reminisce about Don Johnson not as a murderer about to be executed, but as a friend about to die. “I don’t know how to talk about when someone that you’ve known and loved is about to be killed,” Alexander says through tears. “It’s not like he was sick or there’s been a car wreck. There’s nothing wrong with him.” Claiborne is weeping as well. “We’re literally watching someone that we love, someone who is a living testament of God’s redemption and grace be killed by a fellow Christian,” he says. “In this one, that’s what feels incredibly heavy to me.”

I’d already met Claiborne in Lynchburg, Virginia, at a progressive evangelical revival. He’s well known in these circles for being anti-gun violence, anti-war, and, of course, anti–death penalty. While prominent evangelicals like Gov. Lee talk a lot about religion, Claiborne lives his life the way he thinks Jesus would. Alexander is a friend of Claiborne’s and was a regular on the prison abolitionist circuit in Tennessee, showing up to protest during executions.

To the outside observer or those who support the death penalty, Don is a criminal on death row who senselessly murdered his wife. But when talking to Alexander and Claiborne, a more three-dimensional man emerges. “He’s really funny,” Alexander says with a laugh. “He’s got a great sense of humor and he gives really good hugs.” Just a few days earlier, during their last visit together, Johnson gave Claiborne a giant hug and teased him about how thin he is. Claiborne asked Johnson how he was doing. “I’m too blessed to be stressed!” he replied. Even though he was scheduled to die in four days, he was more concerned about how his visitors were handling the situation. “He’s the kind of person who wasn’t angry or bitter,” Alexander says. “And maybe, most importantly, he’s just like us in most ways.”

In Johnson’s clemency petition, everyone—from his spiritual advisors to his fellow inmates—had nothing but praise for the man he had become. “The last half of his 67-year life has been a journey to redeem himself and help others,” said Stephen Schaffer, a Methodist who’s been involved in prison ministry for more than 20 years. “Don is a human being whose flame for good has been reignited.” It’s not uncommon for incarcerated people to find religion while behind bars. There aren’t many statistics about just how many prisoners end up embracing faith, but a 2011 Pew Research survey of prison chaplains found that 73 percent of them say religious programming is critical to rehabilitation.

While listening to Claiborne and Alexander shed tears over the impending killing of their friend, I forgot about how he brutally and senselessly murdered his wife. How was it possible that one person could embody the two greatest extremes of human behavior? And how is it possible for those around him to reconcile those two extremes? In writing about so many men—and they are usually men—on death row, the enormous cruelty of their crimes becomes their identity. Clearly, that is only part of the story.

Vigils for death row inmates on the night of their executions are about as common as a last meal. Capital punishment abolitionists use them as a public demonstration of their opposition to the execution. There were two vigils in Nashville for Johnson. The one at his home church at the Riverside Chapel was explicitly endorsed by Rector and TADP. The other was held outside the prison and organized by the group that Alexander and Claiborne were a part of. When I wondered why there were two different vigils, my audio producer told me about a metaphor for activism someone had once told her. Let’s say there are a bunch of babies in a river coming downstream and they need to be saved. One group will be preoccupied trying to immediately get the babies out of the water, while the other will go upstream to investigate how the babies are ending up in the river in the first place. Rector and TADP are the ones investigating the source of problem, while Alexander and Claiborne are plucking the babies out of the water.

Don Johnson’s execution was scheduled to start at 7 p.m. when he was led into the execution chamber and strapped to a gurney. An hour earlier, members of Riverside Chapel Seventh-day Adventist Church started gathering for a prayer vigil. It’s unclear how many have actually met Johnson, since he’s never been to the church, but Rector is there along with dozens of others. The pastor begins with music, first a few choruses of the “Hallelujah” medley, followed by the group singing Johnson’s favorite hymn, “Amazing Grace.” In front of the pulpit were two large identical posters. At the top was a photo of Johnson’s face and a verse from Romans, “For the wages of sin is death. But the gift of God is eternal life through Jesus Christ, our Lord.” On the bottom half, photos depicting the electric chair and the type of gurney used in lethal injection, with the words “Our Donnie Johnson only has 2 choices!”

I left the church at about 6:20 p.m. to head to the prison, and 20 minutes later I stood among the demonstrators. Everyone from the earlier action at the state capitol was present, as well dozens of other people who’d come out to support Johnson and express their opposition to capital punishment. Inside the prison walls, the execution had begun.

Media witnesses would later report that after being strapped to the gurney and while the executioner began administering the lethal drugs, Johnson asked the warden if he could sing. First was “They’ll Know We Are Christians” (“And they’ll know we are Christians by our love, by our love…”). Then he began the old spiritual “Soon and Very Soon.” His voice was strong when he starting singing, “Soon and very soon we are going to see the King,” but after singing “no more dying here,” it gave out. At this point, according to media witnesses, for three minutes Johnson made what some said sounded like gurgling and gasping sounds, and others compared to snoring. Then he let out a high-pitched scream.

Outside the prison, night had fallen after a colorful sunset. Someone who was in contact with those inside informed the crowd that Don Johnson was dead.

The group exchanged hugs and handshakes and slowly wandered back to their cars. On the drive back home, I wondered what it was like for the witnesses of the execution. Those in the viewing room are usually a combination of family members of the victims, or of the inmate, or sometimes both, plus prison chaplains and media witnesses. In Johnson’s case, Henry and a few members of the media were present as he died. I tried to imagine what it would be like to watch someone take those last, struggling breaths.

I don’t know if I could handle it.

The ever-present threat of executing an innocent person is the kind of worry that can keep you up at night. According to a 2014 study by researchers in Michigan and Pennsylvania, 4 percent of defendants sentenced to die are actually innocent. Since 1973, 166 inmates have been exonerated from death row, and the Death Penalty Information Center estimates that at least 15 innocent people have been executed.

The next morning, I met April Alley, the daughter of Sedley Alley, who, in 2006, was executed even though pressing questions about his possible innocence remained. We met at a downtown coffee shop. Alley is in her 40s now and lives in Louisville with her dogs. She has a slight Southern drawl and speaks with the soft voice of someone who’s seen enough tragedy to last a lifetime. It’s been 13 years since Tennessee executed her father for the rape and murder of 19-year-old Suzanne Collins near Millington Naval Base. On July 11, 1985, at around 10:30 p.m., Collins, who was set to graduate from aviation school the next day, went for a jog and never returned. Two witnesses, Mark Shotwell and Mike Howard, described seeing a brown station wagon driving erratically and hearing Collins’ screams.

“My dad was always very gentle and protective of me,” April told me. It was her first time back to town after her father’s execution in 2006. She thought that after more than a decade she’d be more composed, but the tears started almost immediately. “For several years, I didn’t visit him,” she said. “I allowed a family member to persuade my thinking in assuming he was guilty.” But after reading more about the case and talking with Sedley’s lawyers, she started to doubt his guilt.

Sedley Alley, who was 6 feet, 4 inches tall, with light skin and long red hair, was driving a brown station wagon with his wife when he was pulled over by law enforcement, who were looking for a similar car. After some questioning, the officers decided that Sedley and his wife were in a domestic dispute and sent them home.

Collins’ body was discovered along with physical evidence including clothing believed to be worn by the perpetrator. The hunt for the brown station wagon driver was back on, and Sedley was arrested and interrogated at the naval base. At first, he denied killing Collins, but just 12 hours later he signed a statement admitting that while black-out drunk, he hit Collins with his car, stabbed her in the head with a screw driver, and then killed her with a tree branch. There was just one problem: Sedley’s confession did not match the physical evidence at the crime scene, which, according to the autopsy report, revealed Collins had been struck in the head and neck more than 100 times and a 30-inch tree branch had been inserted into her vagina, perforating her lungs. Sedley took law enforcement officers to the location where he said it happened, but it was not the location where the witnesses had said the victim was abducted. Jurors heard about Alley’s confession at trial but did not know that he initially denied it, nor about the differences in the physical evidence, or his unsuccessful request for an attorney during the interrogation.

For some of us, our anger and frustration comes out loud and uncontrolled, but April’s voice was steady and soft. She swallowed back tears recounting a conversation she had with her dad in prison. “He told me that if he did it…he did not remember doing it. And if it [his guilt] could be proven to him with DNA testing, he didn’t want to fight his execution…but we never got that chance.”

Family of Sedley Alley

In 2001, Tennessee passed a law allowing people convicted of crimes to apply for DNA testing at any time. Central to the Suzanne Collins murder was red underwear believed to belong to the perpetrator but was much too small for someone the size of Sedley. There were also other items of clothing recovered at the scene that could be tested for DNA. Sedley’s lawyers concluded their client had been the victim of a false confession. Despite filing two petitions to have the DNA at the crime scene tested, Sedley was denied.

On June 28, 2006, Sedley Alley was executed at Riverbend Maximum Security. His last words were for his son and daughter. “I love you, David. I love you, April. Be good and stay together. Stay strong.” It’s hard for April to contend with a reality in which her father was executed for a crime he didn’t commit. “How many other families, daughters, or sons are going to have to go through what I’ve gone through?” she wonders. “How many more are innocent?”

Last fall, the Innocence Project received a tip about a serial offender in Missouri. Thomas Bruce, who has been indicted in Missouri, could be the person who actually killed Collins. The Innocence Project relaunched the effort to test vital DNA that could prove Tennessee executed an innocent man. “I felt like someone punched me in the stomach as hard as they could,” April says about hearing from Kelley Henry that they were going to try to prove Sedley didn’t kill Suzanne Collins. “It ripped me apart.”

I don’t know if I expected the governor of Tennessee to immediately assemble a commission to discuss capital punishment, but as I drove away from my interview with April Alley, I was overwhelmed by a feeling of “Is that it?” Even though I’d spoken to so many people about Don Johnson, the family members of victims, and faith leaders, and attended a vigil at a prison, I felt like I had only scratched the surface. There was still the prosecutor who pursued the death penalty 30 years ago, the jury of Johnson’s peers who’d decided that death was a fitting punishment for his crime, and the prison staffer who injected the inmate with a lethal dose of drugs. A lot of those aspects about the death penalty are shrouded in secrecy. This is not by accident.

The day Johnson was executed, Henry went back to her office to secure her files on everything that had happened that evening. The strange coughing noises Johnson made in the execution chamber, Henry believed, indicated suffering. His files could be used in future challenges to the death penalty. “Don believed that his death must have some greater meaning,” Henry told me. At 5:30 the next morning, she and her team flew to Miami for a conference. At 11 a.m., Charles Wright, a 64-year-old death row inmate, died while awaiting execution. Wright, who Henry represented, had been dying of terminal cancer and was scheduled to die on October 10. Johnson and Wright had grown close over their decades behind bars. “I can’t help believe that when Don was killed, he finally gave up,” Henry says. She was sitting in a meeting about another case when she got the news about Wright’s death, and everything that had happened over the last 24 hours sunk in. “I was just overwhelmed at that point,” she said. “I just burst into tears.”

Right before an execution, it’s easy to focus on the inmate or the anti-abortion Christian governor whose beliefs don’t quite extend to opposing capital punishment. But visiting Nashville, I saw vividly how an execution resonates far beyond the perpetrator, the criminal justice system, and perhaps the victim’s family. And yet, it is a system in equilibrium, with a strange interdependence between those opposed and those in favor. Capital punishment tears families apart, forces people to reckon with what they believe in, and affects many people: prison chaplains, local religious institutions, the legal community, family members, and friends of the victims. We know that the death penalty is racially biased, that there’s an unknown number of innocent people waiting to die, and that it does nothing to prevent more victims from being created. I keep thinking of what Jeannie Alexander said about Johnson: “And maybe, most importantly, he’s just like us in most ways.”

And the system grinds on in Tennessee. Stephen West is scheduled to die at Riverbend on August 15.