Before her son began school last year, Tiffany Gordon showed his father’s mugshot to school administrators. “If you see this guy, you have to call the police,” she told them.

Ten years earlier, when Tiffany was 12, a young man she knew invited her, her sister, and a friend on a late-night car ride. “I thought we would be going to McDonald’s,” Tiffany recalls. Instead, 18-year-old Christopher Mirasolo raped Tiffany and took the girls to an abandoned house in eastern Michigan.

When the hiding place was discovered, it marked the end of one nightmare—and the beginning of another. A month later, Tiffany realized she was pregnant. A prosecutor filed charges against Mirasolo, who might have faced a mandatory sentence of 25 years to life for impregnating a minor if he had not pleaded guilty to attempted rape, which resulted in a prison sentence of just two years. A judge let him out less than a year later. Not long after, Mirasolo raped another young girl and was sentenced to 5 to 15 years behind bars.

Tiffany’s parents supported her decision to keep the baby. Other family members urged her to consider an abortion. But she was adamant: “My son was innocent,” Tiffany, now 23, remembers telling her family.

She dropped out of school and stayed afloat working odd jobs. For almost nine years, she didn’t speak about the assault and tried to suppress the memories—until 2017, when she applied for state assistance. Without looking into the circumstances of how she became pregnant, county probate judge Gregory S. Ross granted Mirasolo joint custody and ordered Tiffany to live within 100 miles of him. Making matters worse, Ross disclosed Tiffany’s address to Mirasolo and ordered that his name be added to her son’s birth certificate, according to her lawyer, Rebecca Kiessling.

Tiffany’s experience battling her rapist for parental rights is not unique. As many as 32,000 women get pregnant through rape every year, and at least one-third decide to raise the baby instead of getting an abortion or choosing adoption. But because more than a third of all states do not terminate an assailant’s custody rights unless he’s been convicted of felony sexual assault, the women who make that choice can be forced to co-parent with their rapist. Even in states that make it easier to deny rapists’ parental rights, loopholes abound, and prosecutors and judges have broad discretion in these cases.

That many rape survivors are forced to share custody with their assailants gained fresh relevance this spring, when Alabama lawmakers passed a near-total ban on abortion, with no exceptions for rape or incest. Critics said the law was tantamount to forced motherhood and pointed out that Alabama was one of only two states with no law barring custody rights even when the assailant was convicted of first-degree rape. At the center of the debate was Tiffany’s lawyer. Kiessling supports abortion bans even in cases of rape but she is also fighting for laws to protect rape survivors who do not want to share custody with their assailants. As such, she sits at an unusual confluence of arguments over women’s rights and has become a thorn in the side of legislators who have pushed laws that force women to carry their pregnancies to term without considering their impact on rape survivors. For Kiessling, ending all abortions shouldn’t mean rapists can claim shared custody. “There is nobody more vulnerable than a pregnant rape victim, so you’ve got to protect her,” she says.

Following significant media attention, thanks to Kiessling and a petition signed by more than 140,000 people, Ross reversed his decision granting Mirasolo custody in October 2017, saying he was not aware of Tiffany’s rape. But facing her rapist in court retraumatized Tiffany. The custody case “should never have been filed. That should be up to her,” Kiessling says. Two years after the court battle, Mirasolo’s probation has ended, and with it, the no-contact order, Tiffany explains. She worries that Mirasolo could drop back into her son’s life. “Does he show up and kidnap him? I don’t know,” Tiffany says. “Could he show up at his school and take him?”

For decades, the majority of states let convicted rapists exercise custody over the children conceived in their crimes. In 2015, President Barack Obama signed the Rape Survivor Child Custody Act, which encouraged states to pass measures terminating a father’s parental rights when there was “clear and convincing evidence” of rape. Those that did would receive additional federal funding for violence-prevention programs. The measure took aim at an imbalance in custody law: Rape is one of the few crimes for which a conviction is necessary to end parental rights. In every state, only “clear and convincing evidence” is required to sever custody in cases of child abuse and neglect.

Thanks to the work of victims’ rights advocates, half of all states now use the clear and convincing evidence standard in rape custody cases.

Proponents of terminating rapists’ parental rights say requiring a conviction makes no sense, since rapes are underreported and fewer than 1 percent of rape cases result in a felony conviction. Rapists sometimes use the threat of parental rights to coerce women to drop charges or requests for child support. “It’s important to consider the impact co-parenting has on a mother who is thus confronted again and again with the trauma of rape,” says Shauna Prewitt, a lawyer who was allegedly raped in her final year of college, gave birth to a daughter, and went head-to-head with the father in court. “Depression, not able to work, extreme fear, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder.”

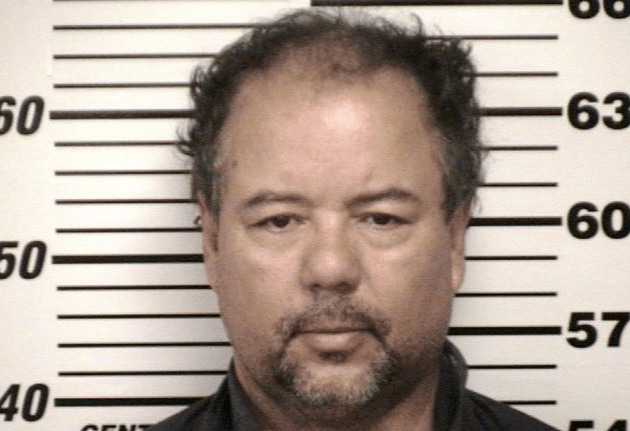

Pro-life and victims’ rights advocate Rebecca Kiessling (Brittany Greeson for Mother Jones)

That struggle is familiar to Jessica Stallings. At 32, she’s only recently started to talk publicly about the abuse that poisoned her childhood. When she was 12, her mother’s 19-year-old half brother moved in with her family in Alabama. He raped her repeatedly, Jessica says, and she got pregnant and had a miscarriage within a few years. To this day, Jessica wonders why her doctor didn’t inform authorities as required by state law. “At the time I was just scared,” Jessica says. “But now I’m thinking, ‘Why was something more not done?’”

A family member pressured Jessica to marry her uncle. She got pregnant again at 15, 17, and 18. Her surviving sons are now 16 and 13 years old. Her second child, who would be 14 now, was severely disabled due to Krabbe disease, a nervous system disorder. He lived only two years. Jessica has his nickname, Pooh, tattooed on her right wrist.

Her uncle continued to abuse her, and after a particularly frightening attack, she finally fled. “I’ve got to get out of here or he’s going to kill me,” she remembers thinking. In 2009, while the divorce was pending, a judge granted her a protection order. Without family support, Jessica became homeless. The courts gave the father full custody.

She eventually married again, found a job as a radio marketer, and had two more children. In 2012, she regained custody of her two oldest sons. After their father tried to exercise his visitation rights in 2015, she decided to seek criminal charges against him. She finds it hard to understand why a grand jury declined to press charges.

Meanwhile, she kept fighting for full custody. Jessica sent the family court judge 30 handwritten pages detailing the incest and abuse she had experienced. The courts ruled the evidence inadmissible and said that Jessica had to let her sons see their father twice a week. “I have to pay for this monster to see my children,” she says. “But I don’t want this monster to live in the same galaxy.”

In 2017, Jessica was scrolling through Facebook, saw an article about Kiessling’s work, and joined an online support group for women who became pregnant through rape. Kiessling, who herself was conceived in rape, started the group eight years ago through her organization Save the 1, which advocates that “all pre-born children should be protected by law and accepted by society, without exception and without compromise.” The groups connect women like Jessica and Tiffany, who share Kiessling’s belief that abortion is immoral. In total, the groups have about 600 members.

Kiessling found Jessica a family lawyer in Alabama, Tanya Hallford, who took on her custody case pro bono. At the end of 2017, she again sought criminal charges, but Jessica says she has since heard nothing. “The first time I went to the grand jury, they told me there wasn’t enough evidence,” Jessica says, “but the second time I went, I had all these mounds of evidence. It looks black and white to me.”

Even charges of first-degree sexual assault do not always untangle survivors from their rapists. In 2011, 18-year-old Noemi Martinez became pregnant after she was raped by a co-worker. Though her attacker admitted they’d had intercourse, a prosecutor and a judge let him plead down to third-degree sexual assault.

“Prosecutors are so used to getting cases off their docket because they are so overwhelmed. They’re just so used to giving plea deals and getting rid of the cases as fast as they can,” says Kiessling. While she was pregnant, Noemi got a restraining order against her rapist, who had been harassing her. “He was telling me to beat myself in the stomach. He was telling me to fall down a flight of stairs and text him when it was dead,” she recalls. But when she applied for Medicaid, the state contacted the perpetrator. He demanded visitation rights—and a court granted them. Every other week, Noemi has to leave her daughter, now 7, with him for an entire weekend.

In the following years, Nebraska lawmakers tried to change the state’s rape custody law, and Noemi supported their efforts. “Personally having to have contact with this person after what happened was terrifying, but now having to share my daughter with no supervision is worse,” she wrote in a statement to the state legislature’s Judiciary Committee in 2017. “I was told that it is in the best interest of my child to have a father in her life. And what makes this rapist safe to be a father?”

That year, Nebraska changed its law so that anyone convicted of sexual assault can be barred from claiming parental rights over their victim’s child. But the new law doesn’t apply retroactively; since her assailant took his plea deal in 2011, it won’t help Noemi.

This May, as Kiessling was in touch with Jessica about her ongoing custody ordeal, Alabama’s governor signed a sweeping abortion ban in the hopes that the Supreme Court would step in to the inevitable battle and overturn Roe v. Wade. Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, Kentucky, and Ohio have also passed laws this year banning abortion after 10 weeks of pregnancy, with no exceptions for rape. (None of the laws have taken effect.)

Previously, most abortion restrictions included rape and incest exceptions to make them more politically palatable. Yet before the final vote on the Alabama bill, Republican lawmakers made clear that in the event the Supreme Court upholds the ban, they’d prefer its restrictions be as expansive as possible. Some legislators expressed misgivings. “Even if this is just a legal strategy, I also have a 16-year-old daughter. Would I want her to carry a baby from a rape?” state Sen. Cam Ward wondered aloud to the Washington Post. “That’s where my stomachache comes in…That’s where folks feel real sick about this.”

Both Kiessling and Jessica support Alabama’s new abortion ban, but they believe such laws need to go hand in hand with more protections for rape survivors. After public outcry and criticism of the ban’s lack of rape exceptions, lawmakers passed a measure terminating custody rights for convicted rapists, but only for first-degree assault or incest.

And Senator Ward’s ambivalence shows the contradiction in Kiessling’s agenda: many women impregnated through rape who would otherwise get an abortion will be forced to carry their pregnancies to term. “Closing these loopholes misses the point for what some women want,” says Mary Ziegler, a legal scholar who has written two books on the fight over abortion.

Alabama’s custody protections won’t help Jessica, whose abuser was never charged. She would like to ask state lawmakers to update the statute to use the clear and convincing evidence standard. “There are so many people who [the bill] is not helping,” Jessica says. “Right now we are telling them, ‘You have to have your baby andyou’re going to be tied to your rapist for the rest of your life.’”

Kiessling is trying to provide that opportunity. She is working with an Alabama legislator to strengthen the custody law and hopes Jessica can testify in support of a new bill. “Because they think this doesn’t happen. They need to have Jessica in front of them, saying, ‘You really believe this is right?’ You are going to tell this woman that?”

Meanwhile, Kiessling is turning her attention to closing the parental rights loopholes that remain in most states, including in Kentucky and Ohio, which still require sexual assault convictions before parental rights can be terminated. “It is frustrating because they think, ‘Well, we just passed a law on this,’ and I have to explain to them, ‘No, you didn’t, because you require a rape conviction.’” She’s pushing lawmakers in her home state of Michigan to introduce the Pregnant Rape Victim Act, which would prohibit judges from letting an accused rapist plea down to attempted rape if the victim gets pregnant. If the act passes, it would be one of the first of its kind and would prevent cases like Tiffany’s from happening again.

Tiffany is supportive of the initiative and wants to be involved in pushing it forward. “I was raped several times,” she says. “Once by my rapist, and twice by the courts.”

This story was made possible with the support of the Solutions Journalism Network and the International Women’s Media Foundation. Additional research and reporting by Marisa Endicott.