There are no two ways about it: Humankind is, for the first time in our recorded history, living through a massive global climate shift of our own making. Science paints today’s crisis as unprecedented in scope and consequence. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t historical cases of societies that have enjoyed the highs and endured the lows of natural climatic changes—from civilization-busting droughts to empire-building stretches of gorgeous sunshine.

Whether they’re commanding marauding armies or struggling with dramatic temperature shifts, today’s leaders have a variety of historical role models they can learn from:

Should Gov. Jerry Brown—confronted by California’s 500-year drought—be mindful of the policy mistakes made by the last Ming emperor?

Will President Obama learn lessons from Ponhea Yat, the last king of the sacred city of Angkor Wat, when planning how to safeguard America’s critical infrastructure against extreme weather?

Will Vladimir Putin channel his inner Genghis Khan as Russia seeks new territories in the melting Arctic? (He’s already got the horse-riding thing on lockdown.)

Here are four historical figures whose triumphs and defeats were related, at least in part, to major changes in their climates.

A new study published this week argues that Genghis Khan, the massively successful Mongol overlord who stitched together the biggest contiguous land empire in world history, may have had a secret weapon: really nice weather.

The paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences presents evidence from tree ring data collected in present-day Mongolia. It shows that when Genghis Khan was building his empire, the usually frigid steppes of central Asia were at their mildest and wettest in more than 1,000 years. This potentially favored “the formation of Mongol political and military power,” the paper says.

The researchers, led by Neil Pederson, a tree-ring scientist at Columbia University, discovered 15 consecutive years of above-average moisture in Mongolia. This was great, politically speaking, for nomad types: “The warm and consistently wet conditions of the early 13th century would have led to high grassland productivity and allowed for increases in domesticated livestock, including horses,” the authors write. If you’ve seen any cheesy historical reenactments of Khan, you’ll know horses were key to expansion, in the same way that icebreakers are becoming all-important in today’s race for shipping routes—and geopolitical influence—in the melting Arctic.

Genghis Khan and his horde may have had successful romps across the warm climes of Central Asia, but the scientists say the weather was temporary, and their analysis reveals worrying trends for the future. Tree rings show that the early 21st-century drought that afflicted Central Asia was the worst in Mongolia in more than 1,000 years, and made harsher by the higher temperatures consistent with man-made global warming. As temperatures here rise more than the global mean in coming decades, the authors say we could witness repeated instances of mass migration and livestock die-off: “If future warming overwhelms increased precipitation, episodic heat droughts and their social, economic, and political consequences will likely become more common in Mongolia and Inner Asia.”

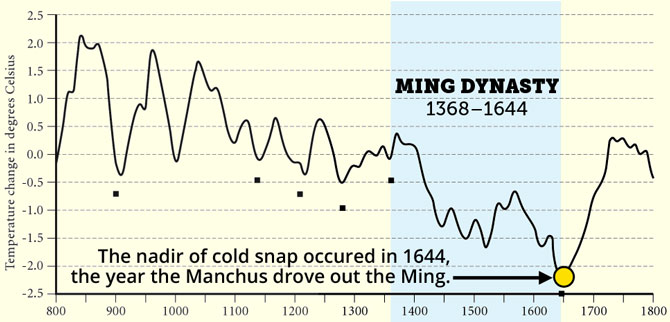

For three centuries, China’s Ming Dynasty was a superpower that, among other things, invented the bristle-headed toothbrush. But from around 1630, the country was ravaged by a record-breaking drought that was caused by some of the weakest monsoons of the last 2,000 years, which in turn sparked mass civil unrest. Anthropologist Brian Fagan writes in his book The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History, 1300-1850 that these events in China were “far more threatening than any contemporary disorders in Europe.” By the time of the fall of the Ming Dynasty in the mid-1600s, Fagan writes, the usually fertile Yangtze Valley had suffered from catastrophic epidemics, floods and famine that drove political discord and left the state vulnerable to attack.

Temperatures were at an all-time low. In China, “it was colder in the mid-seventeenth century than at any other time from 1370 to the present,” writes Emory University historian Tonio Andrade in his 2011 book, Lost Colony. “It was also drier. 1640 was the driest year for north China recorded during the last five centuries.”

As Andrade writes, even “the best government would be tried by such conditions.” And Chongzhen’s government was hardly the best. As crop yields collapsed, the response from the emperor’s already fragile regime exacerbated the crisis. Zero tax relief meant starving farmers “now abandoned their land and joined the outlaws,” writes Geoffery Parker in Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century. The hermit-like emperor in Beijing walled himself off in the Forbidden City, the most famous Ming Dynasty symbol of power, distrustful of lawmakers and bureaucrats who were themselves absorbed in bitter factional disputes. (Sound familiar?) Instead of keeping law and order in the provinces, the emperor withdrew his troops to the capital, basically ceding his empire to the disaffected packs of bandits that were growing in number every day, and he shut down one-third of the “courier network” that he relied on for communications, leaving him blind to worsening developments.

?

?

Meanwhile, the Manchus were ravaging the north, driven by their own drought. It all became too much for Chongzhen. “Under the cumulative pressure of so many catastrophes in so many areas,” writes Parker, “the social fabric of Ming China began to unravel.” Forced to choose between abandoning the north for the southern capital, Nanjing, or standing his ground, “on the morning of 25 April 1644, abandoned by his officials, the last Ming emperor climbed part-way up the hill behind the forbidden city and hanged himself,” writes the University of North Texas’s Harold Miles Tanner in China: A History.

The Manchus eventually sacked Beijing and started the Qing dynasty.

According to author and environmental commentator Fred Pearce, the balmy days of the 10th and 11th century favored the creation of Viking settlements in Greenland under Erik the Red. His son Leif Erikson was the gallant Viking king credited with the first European discovery of North America, at Newfoundland, in the late 10th century. But the period of great adventure and productivity Erikson initiated in Greenland was soon under threat from increasingly cold weather.

“The settlement on the southern tip of the Arctic island thrived for 400 years, but by the mid-fifteenth century, crops were failing and sea ice cut off any chance of food aid from Europe,” writes Pearce in his book, With Speed and Violence: Why Scientists Fear Tipping Points in Climate Change. It was a failure of adaptation more than anything else, Pearce argues. The Vikings stubbornly continued to farm chickens and grains—warmer weather practices—instead of hunting seals and polar bears, and as a result, “creeping starvation had cut the average height of a Greenland Viking from a sturdy five feet nine inches to a stunted five feet.”

In the book Our Dying Planet, University of Windsor scientist Peter Sale writes that the last recorded event in Norse Greenland—once a verdant place from where grapes and timber were traded—was a wedding in 1408. Sale says the expansion and collapse coincided with the “Medieval Warm Period” (9th to 13th centuries) and the subsequent “Little Ice Age” (14th to 19th centuries), in which temperatures dropped by as much as one degree Celsius. “One degree can make a big difference,” he writes.

Trade between Norway and Greenland ceased because ships couldn’t get through the freezing seas. The lush Greenland of Erikson’s time was doomed, and with it the empire. “Above all, there remains the nagging question,” writes Jared Diamond in his book Collapse. “Why didn’t the Norse learn to cope with the Little Ice Age’s cold weather by watching how the Inuit were meeting the same challenges?” It doesn’t take a leap of imagination to ask ourselves the same question in the face of critical climate challenges. Adapt or die?

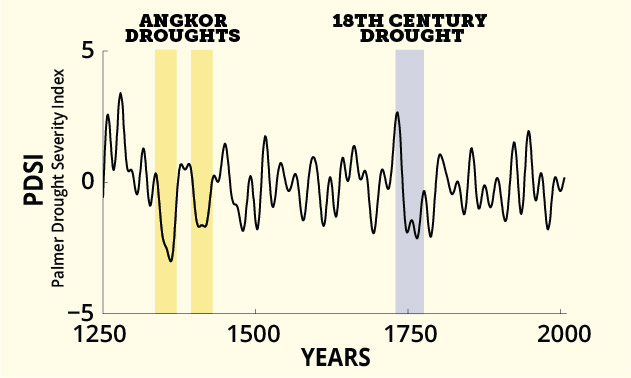

Another tree ring study from the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in 2010 revealed that a multidecade drought may have contributed to the collapse of the Khmer civilization 600 years ago, which was based at the ancient city of Angkor Wat—the largest religious structure in the world.

“I wouldn’t say climate caused the collapse, but a 30-year drought had to have had an impact,” Columbia University scientist Brendan Buckley said in a press release when the study was published.

The kingdom, which stretched across much of Southeast Asia between the 9th and 14th centuries, is most widely believed to have collapsed in 1431 after a protracted war with invaders from present-day Thailand forced the Khmer king, Ponhea Yat, to flee. He eventually founded Phnom Penh, now the capital of Cambodia.

But drought may have made the kingdom much more fragile: Scientists found that the area’s driest year in the last 1,000 years occurred in 1403, three decades before Angkor’s fall. In a cruel twist, the drought was interspersed with damaging monsoonal flooding.

?Angkor Wat boasted a vast and sophisticated irrigation system covering 386 square miles. It was integral to the civilization’s success—the kind of infrastructure we may think of today as a climate resilience strategy, buffering agriculture from the drier parts of the year. But the city’s strength became its weakness. “By the end of the twelfth century it had become a vast and convoluted web of canals, embankments, and reservoirs,” the authors of the 2010 study write. Infrastructure of this complexity becomes resistant to change and “vulnerable to the risk of massive, unrecoverable damage,” requiring an unsustainable level of labor and investment to maintain.

The system was unmanageable, susceptible to freak flooding. “It finally became overwhelmed by extreme swings between severe droughts and severe floods” writes Diamond in Collapse. “Climate change and erosion weakened the Khmer to the point where they could no longer resist their enemies.” The Siamese invasion polished them off.

In his book, The Great Warming: Climate Change and the Rise and Fall of Civilizations, Fagan is saddened by the futility of even the best climate adaptation solutions, exemplified by Angkor Wat’s magnificent waterworks; the city today, a famous tourist attraction, is “a moment frozen in time, abandoned by its builders when in full magnificence, partly because drought dried up their rice paddies and they went hungry.”

Angkor Wat, he writes, is “silent testimony to the power of climate to affect human society, for better or worse.”