Ernie Brown Jr, a.k.a. Turtleman.Animal Planet

Animal Planet’s hit reality TV show Call of the Wildman came under intense scrutiny earlier this year as the subject of a seven-month Mother Jones investigation into behind-the-scenes animal mistreatment. Now, it’s no longer such a hit.

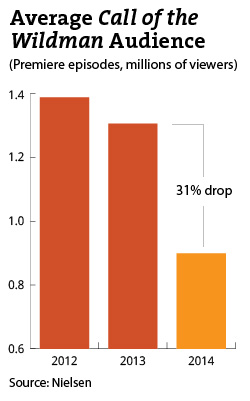

Prime time audiences for this year’s season tumbled by nearly a third compared to 2013—translating to an average loss of more than 400,000 viewers per first-run episode, according to figures supplied to Mother Jones by Nielsen, the media ratings company.

The Mother Jones exposé, published January 21, revealed that the show trapped and caged wild animals to be used in highly scripted and elaborately staged sequences; one Texas installment starred a zebra that had been drugged by handlers before the show’s star, Ernie Brown Jr., a.k.a. “Turtleman”, chased and tackled it to the ground; other cases—which are now under state and federal investigation—include malnourished raccoons, caged coyotes, and bats left for dead in a beauty salon.

The Nielsen data shows that in 2014 Call of the Wildman suffered its worst ratings since the show began in 2011, breaking a two-year stretch of million-plus audiences per episode. The average audience size for the 2012 season was nearly 1.4 million viewers for first-run episodes; last year enjoyed similar numbers of around 1.3 million viewers (up there with blockbuster reality shows like Storage Wars, Keeping Up With the Kardashians, and The Real Housewives of New Jersey). But Season 4, which wrapped up last month, averaged just 900,000, about the same audience for a 5:30 a.m. rerun of Full House on the Nickelodeon channel Nick at Nite. (Nielsen’s numbers for Call of the Wildman excluded specials, repeats, and encore screenings.) Neither Animal Planet nor Sharp Entertainment replied to emails requesting comment.

Nielsen does not make detailed data for individual episodes publicly available, except for the top-line, season-on-season averages mentioned above. But a closer look at figures compiled from the television ratings blog TV by the Numbers, which releases a daily “top 100” list of Nielsen numbers, reveals the extent of the woes for the program.

In 2012, Call of the Wildman reached the top 100 list 15 times, across its Sunday airings (including episodes of Call of the Wildman: More Live Action.) Turtleman did even better in 2013, with 16 appearances in the top 100. But this year, the show made it to the list only once. It never appeared again in the top 100 across the whole season, which ended last month. What’s more, competition was far less fierce this year: It was nearly 20 percent easier to make it to the top 100 list this year than during the same period in 2013.

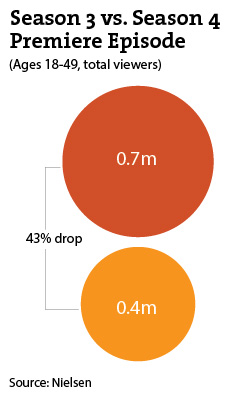

Possibly most alarming for the show’s producers is an apparent drop in the crucial advertiser-targeted demographic of viewers aged 18-49. The season 4 premiere attracted around 40 percent fewer viewers than the previous year’s premiere in this demographic.

Audience losses of this size are a “big deal,” says Paul Dergarabedian, senior media analyst at Rentrak, an audience research firm in Los Angeles. “Any indicator that you’re losing a third of your audience has to be alarming to any television producer or network executive,” he said.

Earlier this year, Animal Planet Canada—the network’s sister channel north of the border—abruptly canceled upcoming episodes of the show just days before a new season was scheduled to air, saying at the time that, “Call of the Wildman has not been resonating with Canadian audiences.”

The show’s formula, which depicts Turtleman’s high-drama rescues of nuisance wildlife by hand, didn’t change between the seasons, save for the final three episodes, in which Turtleman, instead of responding to businesses and family homes, ventures out into the wild with his sidekick Neal James to live off the land and his down-home instincts. (When Turtleman releases a catfish he has caught in a river, Neal solemnly intones via voiceover: “That’s Turtleman. Thinking of the critter first.”)

Ratings analyst Dergarabedian says that while it’s hard to establish direct causality using ratings data, viewers tend to react negatively when bad publicity hits the very core idea of a show: in this case, the treatment of animals. “There’s a trust between an audience and a show about animals that behind the scenes, animals are respected and well treated,” he said. When that trust is broken, an audience will decide quickly whether or not it can “in good conscience continue to support the show.”

Christopher Mapp, an assistant professor of communication at the University of Louisiana-Monroe and contributor to the book Reality Television: Oddities of Culture, says there may well be additional factors involved in Call of the Wildman‘s decline beyond animal mistreatment. “Reality show ratings have been trending downward for a couple of years, both on cable and networks,” Mapp wrote in an email exchange. “This is partly because the novelty wears off. What was once exotic inevitably becomes passé. It’s true that familiarity breeds contempt.”

Despite that, reality television, he says, isn’t going anywhere fast. “Talent, labor, production costs—they’re all so cheap, compared to some genres. Low production costs equal ‘authenticity,’ which works in a reality show’s favor,” he said. “It’s just a winning formula that no one’s willing to abandon. They’re too profitable.”