As Gene Ween, Aaron Freeman was the co-leader of the long-lived alternative cult band Ween, which he started with friend Mickey Melchiondo (a.k.a. Dean Ween) when they were middle-school students in New Hope, Pennsylvania. In 2012, after more than 25 years of recording and touring, Freeman left the group as part of his effort to get sober.

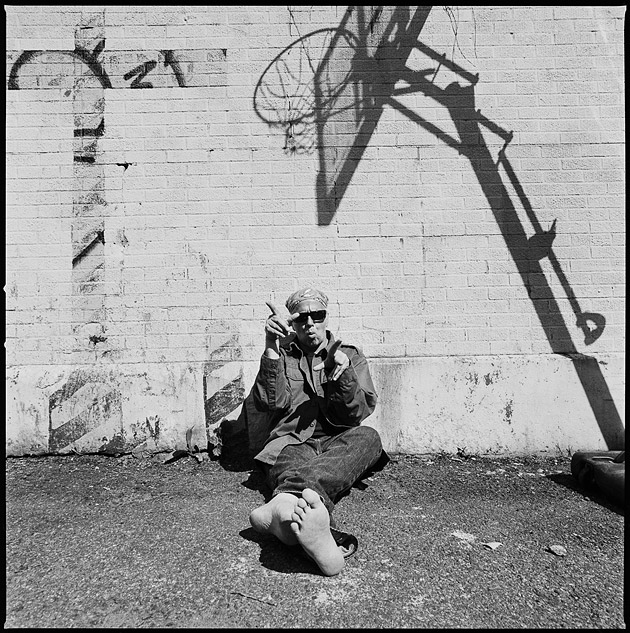

Freeman, out this week, is his first album of original songs since leaving the band. It is an openly biographical and personal album that nonetheless utilizes Ween’s ability to inhabit numerous styles and eras of pop music. The musical reference points of post-Beatles John Lennon and Paul McCartney (“All The Way to China”), Donovan (“Black Bush”), and Cat Stevens (“Golden Monkey”) indicate inspirations that helped carry Freeman through his escape from addiction. I photographed him in Brooklyn, and we spoke again by phone from his home in Woodstock, New York. The following is in his words.

Going through the Ween breakup was really tough. Getting sober was a whole different thing. So there were two levels of it.

For me it’s a lot of patience, because I honestly didn’t know whether I was going to write again. When I write, it always kind of happens all in about a three- or four-week period, where I’ll just go into the zone. A lot of musicians talk about that. I think Bruce Springsteen said that no matter what’s going on in your life, it’s important to keep that one little radar up, because you don’t know when the universe is going to hit you with stuff to write. I really stuck to that concept, and I just waited, and waited, and waited. I would write little things, and record them on the voice memo on my iPhone, little scattered ideas. Then it came.

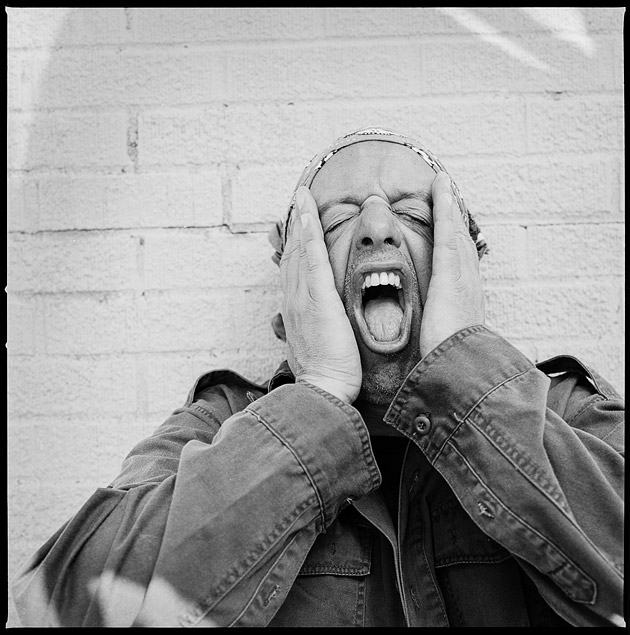

Last summer I was just sitting around, doing my thing, and then all of a sudden I picked up my guitar and boom! The obvious thing would be to put pressure on yourself, like, “Is this record going to be good? It’s the follow-up to 27 years of Ween, and now I’m doing this—what if it sucks?” When I finally got to the point where my subconscious could free itself of that, and it took a while, the songs started coming. I’d go into my room—the typical fucking artist thing—and scream and play my guitar, then come out six hours later, frazzled hair, not showered. My wife and son would look at me like, “Oh hey, he’s out. Do you want any food?” And I’d be like, “Aaaagh, gotta go back in!” That’s how I worked.

I’d like to think that a kid…or a bunch of old bums gathered around a trash can fire…would both fully get it.I’m thinking, “If I get one song, at this point in my life, that’ll be fucking amazing for me and my journey.” That one concept led to a whole record. I’m really proud of it, and really grateful I wrote it. It’s stripped down, no bells and whistles to it. I just wanted to go in, pay attention to the songs, get ’em on tape, and then move on.

No matter what goes on, I’ve written the songs that I love. They’re not very complex. I like to keep the words simple so they’re not too identifiable, and so they’ll last longer. I’d like to think that a kid could listen to it, or a bunch of old bums gathered around a trash can fire keeping themselves warm, they would both fully get it.

One of the things I’ve wanted for years, especially during the last five or so years of Ween, was more honesty. For me, it wasn’t getting sincere. We’d just put on our token songs that were kind of goofy, like “My Own Bare Hands.” Toward the end, it was just kind of…mundane. It would distract from the best parts of Mickey’s and my music.

This record is very autobiographical, it’s like a journal for me of things that I was really into in the last year or so… spiritual things and severe, gut-wrenching love songs.

That first song, “Covert Discretion,” is absolutely typical of me. There’s always been a whole bipolar thing going on with me: I’m pretty shy, or soft spoken, and then there’s the other part. A friend who does astrology told me, “You’re a Pisces, you’re totally water, and then you’ve got this fire planet.” A lot of stuff at the end of Ween was just brutal. I have to write about that stuff, or else I feel like I’m not being honest. If this is a song that calls for fucking brutal honesty, then the most important thing is to do that, and take it so far over the edge. That’s what people love about Ween, they love the honesty and not being scared to go there.

I was susceptible to hard-core addiction because my personality is that way. I think a lot of addicts, serious addicts, have that. They go full throttle and then they are coming down and they are trying to deal with it in a quiet way. It’s typical: I was either fuckin’ naked with a cowboy hat on looking for cocaine all night or I was just completely quiet in my room. And that’s a scary way to be.

“The whole point of this record was to chill the fuck out.”The most wonderful thing about recovery is that you learn to maintain a steady way of being. There is always stimulus, whether it’s positive or negative. Buddhist philosophy really dives deep in to that: You sit with it, you meditate on it, and you let it pass. It is really difficult because you’ve never done that before. In the early stages of recovery, I’d have to go up to my room and just sit there in so much fuckin’ agony and just wait, recognize it, and let it pass. I had this mantra: Just be accountable. I wanted to be accountable for more than a week. It seems so simple, but it’s easier said than done.

In rock music, you don’t have to be accountable for anything! [Laughs.] It didn’t matter as long as I got on stage. For many years, I was fooling myself into thinking that I was going to lock myself away in my dressing room and help myself, and I never did because deep down I wanted to party just like everyone else was.

I think if this album sounds more derivative in certain ways it was because I was more clear-minded. I leaned on music that I loved. There’s a lot of Paul McCartney, John Lennon, XTC, and David Bowie—the things that I hold dear. The whole point of this record was to chill the fuck out. For some reason something made me want to record doubled vocals on almost the entire album, which is awesome. I’ve always had this weird desire to conquer and make perfect double vocals. To get spiritual on you, I really let the universe dictate how this whole thing was going to turn out.

“I had to embrace the fact that my income was going to be a tenth of what it was, but it was still worth it.”

If the music sounds like something I’m influenced by, I accept that and try to make it as sincere and honorable as it can. If it’s going to sound like John Lennon, I’m going to fucking make it sound like John Lennon. I’ll never say, “Oh, this kind of sounds like a Lennon song, so I better make it sound different.” That’s not the way I look at music. I consider myself as kind of a vessel of all these beautiful things that I’ve always heard, and I let it go through me. Of course, it always has my stamp on it, my creativity, but it honors what I love.

Fortunately, I’ve had the ability to never think too much about where I’m going. In Ween, my thing has always been: It doesn’t matter what kind of song it is or where it goes as long as it’s a good song. That’s what Mickey and I always adhered to.

The foremost thing is just writing music, and I’ve been very lucky to have 25 years of that under my belt. The Ween audience is very loyal and they’re great. I want to keep making music for them. I don’t want a big, bombastic career. I’ve been through that. If people want to come, they come. If they don’t, they don’t. I want to do great live shows, because I love performing, and I hope to write songs and maybe have other people pick them up, and make a living off of doing that.

But we’ll see. I have to pay the bills. When I lost Ween and decided to get sober, I had to embrace the fact that my income was going to be a tenth of what it was, but it was still worth it. I really believe if you do the right thing and you make yourself accountable and available, then good things will happen.