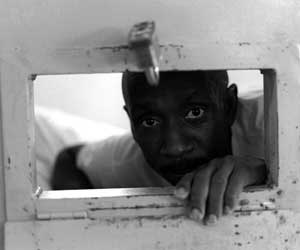

Photo by Adam Shemper

What’s left of Albert Woodfox’s life now lies in the hands of a federal appeals court in New Orleans. By the time the court hears his case on Tuesday, the 62-year-old will have spent 36 years, 2 months, and 24 days in a 6-by-9-foot cell at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola. An 18,000-acre complex that still resembles the slave plantation it once was, the notorious prison, immortalized in the film Dead Man Walking, has long been considered one of the most brutal in America, a place where rape, abuse, and violence have been commonplace. With the exception of a few brief months last year, Woodfox has served nearly all of his time there in solitary confinement, out of contact with other prisoners, and locked in his cell 23 hours a day. By most estimates, he and his codefendant, Herman Wallace, have spent more time in solitary than any other inmates in US history.

Woodfox and Wallace are members of a triad known as the “Angola 3“—three prisoners who spent decades in solitary confinement after being accused of prison murders and convicted on questionable evidence. Before they were isolated from other inmates, the trio, which included a prisoner named Robert King, had organized against conditions in what was considered “the bloodiest prison in America.” Their supporters believe that their activism, along with their ties to the Black Panther Party, motivated prison officials to scapegoat the inmates.*

Over the years, human rights activists worldwide have rallied around the Angola 3, pointing to them as victims of a flawed and corrupt justice system. Though King managed to win his release in 2001, after his conviction was overturned, Woodfox and Wallace haven’t been so lucky. Amnesty International has called their continued isolation “cruel, inhuman, and degrading,” charging that their treatment has “breached international treaties which the USA has ratified, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention against Torture.” Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.), chair of the House Judiciary Committee, has taken a keen interest in the case and traveled to Angola last spring to visit with Woodfox and Wallace. “This is the only place in North America that people have been incarcerated like this for 36 years,” he told Mother Jones.

Meanwhile, the prevailing powers in Louisiana, from Angola’s warden to the state’s attorney general, are bent on keeping Woodfox and Wallace right where they are. The state’s Republican governor, Bobby Jindal, has thus far steered clear of the controversial case. Conyers, though, who has spoken with Jindal about Woodfox and Wallace, says the governor seemed “open-minded.”

For his part, Conyers is optimistic that Woodfox’s fortunes, at least, could soon change. On Tuesday, Nick Trenticosta, who is one of Woodfox’s lawyers, will have 20 minutes to convince the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals to uphold the decision of a district court judge in Baton Rouge, who last July overturned Woodfox’s conviction for the 1972 murder of an Angola prison guard. The murder, for which Wallace was also charged, occurred while Woodfox was already serving a sentence for armed robbery. Trenticosta, a longtime Louisiana death penalty attorney who heads the New Orleans-based Center for Equal Justice, will argue that his client received inadequate representation from his court-appointed attorneys when he was retried in 1998, as well as during his original trial in 1973. Better lawyers, he’ll argue, would have shown that Woodfox’s conviction was quite literally bought by the state, which based its case on jailhouse informants who were rewarded for their testimony. The primary eyewitness to the murder received special privileges and the promise of a pardon. One of the corroborating witnesses was legally blind, while another was on the anti-psychotic drug Thorazine; both were subsequently granted furloughs.

Woodfox’s lawyers will also make the case that the state failed to provide his previous defense attorneys with crucial information about the witnesses—ensuring that they were unable to cross-examine them effectively—and lost physical evidence, which was inconclusive at best, and possibly favorable to the defendant. (A spokeswoman for the Louisiana State Penitentiary said the prison, as a matter of policy, would not comment on an ongoing case.)

Depending on how the appeals court decides, Woodfox may get a chance at another trial, where this time he’ll be represented by a team of highly skilled lawyers. If given that opportunity, Trenticosta told Mother Jones in a recent interview, he and his colleagues will go beyond just refuting the evidence that led to their client’s conviction. They intend to reveal the identities of the real murderers of prison guard Brent Miller, who, Trenticosta says, are now dead. He says his team has “numerous witnesses who saw” the murder and others “who have good information.” (Asked for the names of the witnesses and others with specific knowledge of the murder, Trenticosta said he would reveal their identities only if there is another trial.) Of Woodfox and Wallace, Trenticosta says, “They were targeted. They were set up.” The lawyer believes the state of Louisiana is determined to prevent Woodfox from being retried in order to “cover up a coverup.”

The state’s case against overturning Woodfox’s conviction will be argued by Kyle Duncan, a University of Mississippi law school professor who is an admirer of the jurisprudence of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. He will likely take the usual position in these types of cases, arguing that Woodfox’s previous defense attorneys, despite what Trenticosta might say, had every opportunity to cross-examine the witnesses, so no new trial is warranted. But Duncan is little more than a mouthpiece; the force behind the state’s appeal is Louisiana attorney general James “Buddy” Caldwell Jr. The former prosecutor, who moonlights as an Elvis impersonator, is a politically ambitious Democrat. Since his election in 2007, Caldwell has fought efforts by Woodfox and Wallace to overturn their convictions. After Woodfox’s conviction was overturned last year, Caldwell declared, “We will appeal this decision to the 5th Circuit. If the ruling is upheld there I will not stop and we will take this case as high as we have to. I will retry this case myself…I oppose letting him out with every fiber of my being because this is a very dangerous man.”

Caldwell shares this position with Angola’s warden, Burl Cain, a devout Baptist who has a reputation for proselytizing to the inmates under his watch. Cain, who has likened the Black Panthers to the KKK, is adamant that the aging Woodfox is and always will be a menace to society by virtue of his political beliefs. He has said that Woodfox is “locked in time with that Black Panther revolutionary actions they were doing way back when…And from that, there’s been no rehabilitation.”

After a three-judge appelate panel hears arguments on March 3, it will be at least six weeks, and possibly many months, before it rules on the appeal. If it concurs with the district court’s decision, Woodfox will be retried or released. If it overrules the lower court, his conviction will remain in place, and his defense team will have to go back to the drawing board.

Albert Woodfox’s journey to the East Courtroom of the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals began 40 years ago, when he was convicted of armed robbery at age 21 and sentenced to 50 years of hard labor. After being transferred from New Orleans to Angola in 1971, Woodfox met Herman Wallace and Robert King.

In the early 1970s, Angola—which spans an area the size of Manhattan and is 30 miles from the nearest town—was a lawless, dangerous hellhole. The all-white corrections officers, who were called “freemen,” lived with their families in their own community on the prison grounds, with inmate-servants they called “house boys.” There were just 300 freemen to control an inmate population of more than 3,000—but they were backed by hundreds of so-called “trustees,” supposedly trustworthy convict guards, who were known to abuse other prisoners. In his just-published autobiography, From the Bottom of the Heap, Robert King, who was released in 2001 after proving that he’d been wrongfully convicted of the murder of a fellow Angola inmate, says prison guards stripped prisoners, shaved their heads, and made them run a gauntlet of bats and clubs; incoming prisoners, known as “fresh fishes,” were sold as sex slaves. According to records kept by the prison’s famous newspaper, The Angolite, there were 82 stabbings in 1971, 52 in 1972, and 137 in 1973. (The paper’s longtime editor, Wilbert Rideau, won the prestigious George Polk Award for his journalism while still in prison.)

In his book, King describes the tinderbox atmosphere at Angola when he arrived in 1971. That August, prisoners had organized a hunger strike to demand an end to the inmate-guard system, sexual enslavement, racial segregation, and 16-hour workdays. King sensed a mood of defiance among the prisoners and learned that Wallace and Woodfox were “teaching unity amongst the inmates, establishing the only recognized prison chapter of the Black Panther party in the nation.” He joined Wallace and Woodfox in organizing the prison population to advocate for better living conditions.

It was in this volatile environment that Brent Miller, a 23-year-old corrections officer born and raised in Angola’s staff community, was stabbed to death in a prison dormitory on the morning of April 17, 1972. About 200 prisoners—every one of them black—were rounded up and interrogated. Billy Wayne Sinclair, a white inmate who was on Angola’s death row at the time (he was eventually freed), later told NPR: “You heard hollering and screaming and the bodies being slammed against the walls. Upstairs you could smell tear-gas bombs…We heard the beatings that were going on for weeks after that.” Two days after the murder, an elderly prisoner named Hezekiah Brown came forward, reportedly telling investigators that he had witnessed the stabbing being carried out by Woodfox and Wallace, along with two other inmates. Based on his statements, the local sheriff filed charges against the men he had named.

Brown was the state’s key witness against Woodfox in his 1973 trial. A magistrate judge who reviewed Woodfox’s case wrote last summer that Brown’s testimony was “so critical to [the prosecution’s] case that without it there would probably be no case.” After a federal court overturned Woodfox’s conviction, he was given another trial in 1998, where Brown’s account again figured heavily. At that point, Brown had been dead for two years, but his testimony—without defense objection—was read into the record. In his 1973 testimony, Brown admitted that he had at first said he was not in the dormitory when the murder happened, but then decided to tell “the truth.” According to Brown, the truth was that on the morning of the murder Miller stopped by his bed for coffee, as he often did, and while he was sitting on Brown’s bed, the four men came into the dorm and began stabbing him. (NPR, which did a three-part series on the case last year, interviewed a former Angola inmate who said he was with Woodfox in the prison mess at the time of the murder.)

According to evidence presented at Woodfox’s 1998 trial, Brown was rewarded for his testimony in numerous ways: He was moved to a minimum-security area, where he lived in a house, luxurious by prison standards, and was provided with a carton of cigarettes a week. And a month after the 1973 trial, then-warden Murray Henderson began writing letters to state officials seeking a pardon for Brown, which cited his testimony against Miller’s alleged murderers. During Woodfox’s 1998 retrial, Henderson acknowledged that he promised Brown a pardon in exchange for his help “cracking the case.” It took years, but Brown, a serial rapist serving life without parole, was released in 1986.

A second key witness was an inmate named Paul Fobb, who said he saw Woodfox leaving the dormitory after the murder. Fobb, who was legally blind, was also dead in 1998, and his earlier testimony, like Brown’s, was read into the record without objection by Woodfox’s lawyers. Fobb, who had been convicted of multiple rapes, was granted a medical furlough shortly after testifying, and left Angola.

A third prosecution witness, Joseph Richey, claimed that he saw Woodfox and others exiting the dorm, and on going inside saw Miller’s body. At first he said he thought the inmates were going for help, but after a meeting at the attorney general’s office, Richey changed his statement. He later confirmed being on Thorazine at the time of his testimony, and said he had told the attorney general’s office as much. This information was not given to Woodfox’s defense lawyers in either trial, nor were the juries made aware. Richey was subsequently transferred from Angola to a minimum-security state police barracks, and went on to work as a butler at the Louisiana governor’s mansion. He was even provided the use of state police cars. While supposedly under the watch of the state police, Richey robbed three banks.

Yet another supposed witness, Chester Jackson, never testified at Woodfox’s 1973 trial. Yet in 1998, his statements to investigators were mentioned by prison officials testifying for the prosecution, with only belated objections by the defense that this was hearsay evidence.

Then there was the physical evidence: a homemade knife that couldn’t be linked to any of the accused; a bloody fingerprint that likewise matched none of the men Brown had implicated; and flecks of human blood on Woodfox’s shirt (which he denies he was wearing that day). The bloodstained shirt was lost before the 1998 trial—and before it could be tested for DNA.

In 1973, Woodfox was convicted of Miller’s murder in a matter of hours by an all-white jury. Wallace was convicted just as quickly in a separate trial. It took more than two decades of appeals, but Woodfox finally won a new trial on the basis of “ineffective assistance of counsel”—poor lawyering. Yet the 1998 trial not only failed to reveal earlier miscarriages of justice, but also introduced one of its own: One member of the grand jury that reindicted Woodfox was Anne Butler, ex-wife of former Angola warden Murray Henderson, who had led the investigation of the murder in 1973. She was kept on the jury even after revealing her identity to the district attorney, and despite the fact that she had written about Miller’s murder—and her belief that Woodfox and Wallace were guilty—in the 1992 book she coauthored with Henderson, Dying to Tell, which she reportedly passed around for other jurors to read.

Woodfox began working to secure himself a third trial almost immediately after his second. But a lifeline came to him via another member of the Angola 3, Robert King. Convicted of a separate prison murder and placed in solitary for decades, King ultimately won his release with the help of Chris Aberle, a former 5th Circuit staff attorney who had been assigned to represent him in his appeal. King was convinced that, like himself, Woodfox and Wallace were “victims of frame-up and racism,” he said in a recent interview. He asked Aberle to help them as well, and the lawyer agreed. In 2006, Aberle filed a habeas corpus petition on Woodfox’s behalf with the Federal District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana.

With Aberle and a team of new lawyers fighting for them, King speaking out on their behalf, and a growing support movement, it looked as if 2008 would be a turning point for Woodfox and Wallace. In March, they were moved for the first time in 35 years from solitary to a maximum-security dormitory with other prisoners. The move followed Rep. John Conyers’ visit to Angola and was spurred by a civil lawsuit initiated by the ACLU and carried forward under the leadership of noted death penalty attorney George Kendall, who argued that the Angola 3’s decades-long confinement in solitary violated the constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment. (The case is ongoing.)

Then, in June 2008, a federal magistrate judge named Christine Noland issued a 70-page report in response to Woodfox’s habeas petition. The report recommended that Woodfox’s 1998 conviction be overturned, based on the deficiencies in his defense counsel. It also pointed to the weakness of the state’s case:

At the most, the Court sees a case supported largely by one eyewitness [Brown] of questionable credibility…two corroborating witnesses, Richey and Fobb, both of whom, according to other evidence submitted with Woodfox’s petition, provided trial testimony which was materially different from their written statements given just after the murder, and one of whom’s testimony (Fobb’s) could have been discredited by expert evidence; and no physical evidence definitively linking Woodfox to the crime.

Because, in the Court’s view, the State’s case did not have “overwhelming” record support, confidence in the outcome is more susceptible to and is undermined by defense counsel’s errors…and as a result, Woodfox is entitled to the habeas relief he seeks—that his conviction and life sentence for the second-degree murder of Miller be reversed and vacated.

A month later, in July 2008, federal district court Judge James Brady affirmed Noland’s findings and issued a ruling overturning Woodfox’s conviction. In November, he ordered Woodfox to be released on bail pending a new trial. “Mr. Woodfox today is not the Mr. Woodfox of 1973,” Brady wrote in his ruling. “Today he is a frail, sickly, middle-aged man who has had an exemplary conduct record for over the last 20 years.”

Buddy Caldwell, Louisiana’s attorney general, would have none of it. He appealed Brady’s decision, then moved swiftly to mount an emergency motion to block Woodfox’s release. “We’re…not going to let them get away with that kind of thing,” Caldwell told the press. (Caldwell declined to comment for this story.)

Woodfox’s release was contingent upon him finding a place to live. His niece, who lived in a gated community outside New Orleans, offered to take him in. But an attorney in Caldwell’s office emailed the neighborhood association to warn that a cold-blooded murderer was about to be released into their midst. Woodfox’s niece reported that her neighbors stopped waving to her family and cars began circling past her house, sometimes stopping. “We became afraid for our children,” she said. While his lawyers worked to secure other living arrangements, the court decided to grant the state’s emergency motion, declaring that Woodfox would have to remain in custody pending his appeal.

Caldwell has shown a similar determination when it comes to Wallace, who is pursuing his case through state courts, backed by the same legal team. In 2006 a state judicial commissioner issued a report similar in many ways to Christine Noland’s, recommending that Wallace’s conviction be overturned based largely on questions about Hezekiah Brown’s testimony. But the recommendation was subsequently dismissed by both the district court and its appellate court. Wallace has taken his appeal to the Louisiana Supreme Court, where his case is pending.

Caldwell’s fixation on keeping Wallace and Woodfox locked up mystifies some observers of the case. But in addition to any political motives he may have, Woodfox’s lawyer, Nick Trenticosta, suggests, Caldwell may be seeking to protect the reputation of one of his closest associates and childhood friends, John Sinquefield.

As the district attorney who prosecuted the 1973 case against Woodfox, Sinquefield stands to be tainted by revelations that the state’s key witnesses were compromised—and that he failed to provide key information to the defense team. Magistrate Judge Noland has already criticized Sinquefield’s behavior in Woodfox’s 1998 trial, where he was called as a witness. After Brown’s testimony had been read into the record, Sinquefield, who’s now the chief assistant district attorney for East Baton Rouge Parish, took the stand to describe the dead witness’ delivery of his original testimony. Brown, said Sinquefield, had “testified in a good, strong voice, he was very open, he was very spontaneous, he answered questions quickly, and he was very fact specific.” He also declared, “I was proud of the way he testified. I thought it took a lot of courage.”

In her report, Noland pointed out that Sinquefield’s testimony was highly unorthodox. She noted that “a prosecutor’s statements suggesting that he has personal knowledge of a witness’s credibility” meets the Supreme Court’s criteria for “egregious prosecutorial misconduct.”

Caldwell, for his part, has made clear that he will go to great lengths to keep Woodfox and Wallace in prison, and preferably in solitary confinement (where both men were returned after their brief respite last year). If need be, he says, he will personally prosecute Woodfox for a third time for the Miller murder. And if at any point it looks as if Woodfox will be returned to society—whether on bail or through exoneration—Caldwell has said he intends to launch a prosecution on what he claims are several 40-year-old charges of rape and robbery for which the prisoner was never prosecuted.

Good luck, says Aberle, who notes that Caldwell is referring to an arrest record from the ’60s. Such charges were then commonly used to hold black men, he says, but seldom stuck because they had literally been pulled off a list of existing unsolved rape cases. “Nothing ever happened with any of them,” Aberle says. Caldwell, he adds, “would have to make a case with witnesses he couldn’t come up with 40 years ago.”

After Caldwell, the man who appears most determined to keep Woodfox and Wallace behind bars, is Angola’s current warden, Burl Cain. Known for his prison evangelizing, Cain has set up chapels around the grounds and a host of Bible study classes and other religious activities for prisoners. As described in a glowing 2008 article in the Baptist Press:

Once called the bloodiest prison in America, the Louisiana State Prison at Angola now has a new reputation as a place of hope for more than 5,000 inmates who live out their life sentences without parole. Many inmates know they’ll leave the prison walls only when they die, yet despite their circumstances, there is joy in their hearts.

Credit for this unprecedented transformation is given to its one-of-a-kind warden, Burl Cain, who governs the massive prison on the Mississippi River delta with an iron fist and an even stronger love for Jesus.

The article notes Cain’s special dedication to delivering souls from the death chamber into the hands of Christ. When he supervised his first execution as warden, Cain said, “I didn’t share Jesus” with the condemned man, and as he received the lethal injection, “I felt him go to hell as I held his hand.” As Cain tells it, “I decided that night I would never again put someone to death without telling him about his soul and about Jesus.” Cain believes that there is only one path toward rehabilitation, and it runs through Christian redemption. According to Wallace, Cain has at least once offered to release him and Woodfox from solitary if they renounced their political beliefs and accepted Christ as their savior.

If Cain did indeed make that offer, that’s the extent of the mercy he’s willing to show the men. “They chose a life of crime,” he has said. “Every choice they made is theirs. They’re crybabies crying about it. What they ought to do is look in the mirror and quit looking out.” The appeals panel that reviewed Woodfox’s grant of bail relied heavily on Cain’s statements in deciding to keep the prisoner in custody. According to the court’s stay of release, “The only testimony on whether Woodfox poses a threat of danger was the deposition of Warden Cain, who testified about his impressions of Woodfox’s character and Woodfox’s disciplinary record while in prison. The Warden stated his belief that Woodfox has not been rehabilitated and still poses a threat of violence to others.”

In his deposition, Cain provided numerous examples of Woodfox’s rule breaking: Prison guards, he reported, had discovered five pages of “pornography” in the prisoner’s cell, which, Cain went on to say, “we believe can cause inmates to become predators on other inmates, because they see—the sexual thing arouses them. And so they’re in an environment where there are no females, there is no sexual gratification other than whatever you can create yourself, and then what happens is…it causes homosexuality…and is counterproductive to moral rehabilitation.” On another occasion, Woodfox was found “hollering and shaking the bars on his cell,” a “very serious” offense, Cain said, because the inmate was “absolutely being defiant,” behavior that could cause other inmates to “rack the bars” and even “cause a riot.” Cain rattled off more charges against the man he called a “predator,” ranging from throwing feces at other prisoners to threatening a hunger strike. Cain said that Woodfox had made a “telescopic” pole of compressed paper that could be used as a spear or a blowgun. Woodfox had also been found with an empty Clorox bottle, something escaping prisoners used as “flotation devices,” according to Cain, when making their getaways down the nearby Mississippi River. The majority of these violations—25 of them over 36 years—had occurred more than 20 years earlier.

Cain has made clear that one of the reasons he thinks Woodfox and Wallace are dangerous is his belief that the prisoners are moles for the Black Panthers, who might take the opportunity to start a revolution in the prison if they are released from solitary. If they’re let out of prison altogether, Cain suggests, they will take their militant agenda to the streets. In his deposition, he stated that Robert King is “only waiting, in my opinion, for them to get out so they can reunite.”

“Reunited for what reason?” asked Nick Trenticosta.

“Because he passes out little cookies with the panther on them,” Cain said, apparently referring to the logo of King’s homemade candy business. (King began making pralines—which he now dubs “freelines”—while still in Angola, using a makeshift stove fashioned out of soda cans and fueled by toilet paper.) “If he passed out those cookies with KKK on them, it would be no different to me. He would be guilty. If you build your life on hatred and you’re hung up back 20 or 30 years ago, and we have moved onto society past that, you can’t go back reliving in the public. You’re dangerous…You can keep until the cows come home; I’m never going to tell you he’s not violent and dangerous, in my opinion. I just can’t do it.”

Asked by Trenticosta to assume, for a moment, that Woodfox was not guilty of killing Miller, Cain insisted that his treatment of the prisoner would remain unchanged.

“I would still keep him in CCR [solitary confinement],” he said. “I still know that he is still trying to practice Black Pantherism, and I still would not want him walking around my prison because he would organize the young new inmates. I would have me all kind of problems, more than I could stand, and I would have the blacks chasing after them [Woodfox and Wallace]…He has to stay in a cell while he is at Angola.”

Asked to define “Black Pantherism,” Cain replied, “I have no idea. I have never been one. I know they hold their fists up, and I know that I read about them, and they advocated violence…Maybe they are nice good people, but he is not.”

When Trenticosta pressed him on why Woodfox was dangerous, Cain grew angry. “What can I say? He’s bad. He’s dangerous. I believe it. He will hurt you…They better not let him out of prison.”

*Among the activists who have taken up the cause of the Angola 3 were Anita Roddick, the late founder of the Body Shop (who was also a Mother Jones board member) and her husband, Gordon. The Roddicks’ family charity, the Roddick Foundation, contributed funding for this story.